A peek into the Rotunda Library & Archive

Where did the Gallery's Rotunda Library & Archive collection come from? What does the Rotunda Library & Archive do? All these questions and more answered with a peek into the collection, history and uses of the newly renovated Rotunda Library & Archive.

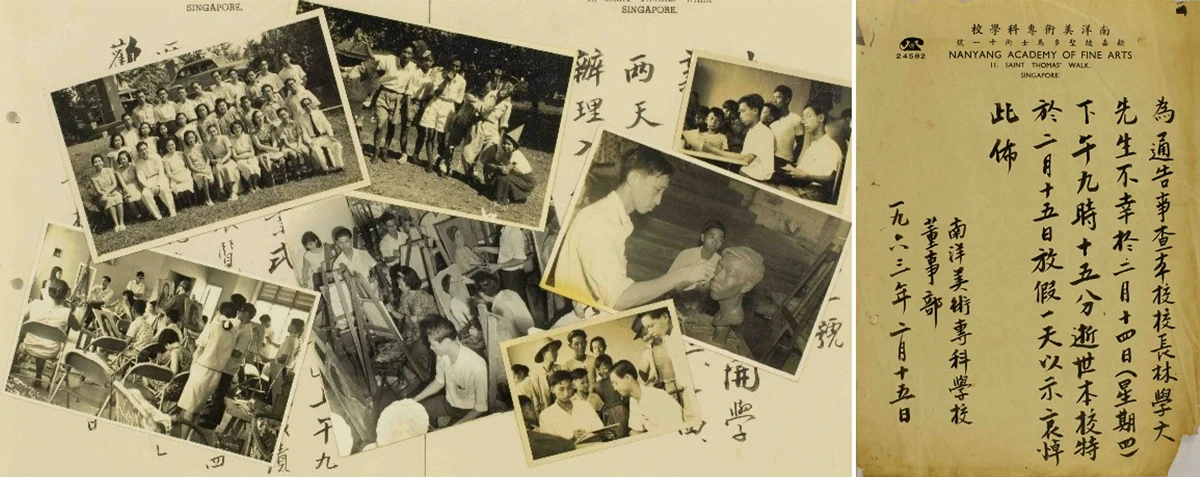

(Right) Notice from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts board of directors, dated 15 February 1963. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lim Yew Kuan. RC-S67-LHT2.5-198.

A museum library and archive is a unique entity in that it often exists as a microcosm within the larger ecosystem of the museum. It manages its own collection and catalogue of materials; it tends to serve a smaller, more focused group of users within the museum-going community; it may even have its own operating hours different from that of the museum if it is open to the public. Quite often its users may bypass the museum entirely, choosing to spend a whole day conducting research in the library and archive. No matter how many researchers are using the space, the general quietness of museum libraries may present a stark contrast from exhibitions or public programmes happening at other spaces. In addition, one common predicament of museum libraries is that they “are often located far from galleries and visitors, in restricted-access office space, or even in separate buildings”1, which was a problem the Gallery used to face.

The National Gallery Singapore’s reference and archive collection was previously tucked away at the Resource Centre at Level 4M and 3M of the Supreme Court Wing, which made it less visible to the public and difficult for researchers and docents to access. In a bold move, the library and archive collection has now been brought into the Rotunda at the heart of the Gallery and the space renamed the Rotunda Library & Archive. By placing the library and archive collection centrally within the UOB Southeast Asia Gallery and into the main route of visitors, the Gallery hopes that visitors can view the library and archive collection as existing alongside the artwork collection, and in turn encourage them to explore beyond the artworks by seeking additional information from published references and primary archival sources available at the Rotunda.

One might ask, why is the Gallery giving emphasis to a library and archive within the museum, and what is the purpose of a museum library and archive?

Instead of being just another department or office within the museum, a museum library and archive can realise its full potential when its holdings and functions are viewed as extensions of the museum’s collections and facilities. The idea is “to view the book not only as an information-carrying device, but as an object in its own right and the librarian also as a curator. … [B]ecause the museum library provides a niche for special collections of related material, the museum’s mission and its collection of objects are enhanced, amplified and enriched through the museum library.”2

Where did the Rotunda Library & Archive collection come from?

The National Museum Art Gallery, one of the precursors of National Gallery Singapore, opened in 1976 inside today’s National Museum of Singapore (NMS). It featured paintings and sculptures collected since its beginnings as the Raffles Library and Museum, alongside 110 paintings donated by art philanthropist Dato Loke Wan Tho in 1960. Constance Sheares, curator of art at the museum, noted in the catalogue of their official opening the existence of “a departmental library of approximately 15,000 volumes of books, journals and other publications on anthropological, historical and art subjects… The holdings of the departmental library were acquired by the National Museum through purchase and an exchange programme of publications with museums, universities, institutions of higher learning and learned societies, as well as through an exchange programme between the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society … and other institutions.”3

Ms Tan Chor Koon, librarian in charge of the NMS’ Resource Centre since 1993, recalled how in the beginning “the library served multiple purposes, such as a storage space… Our most unique collections are old books from the Raffles Library, and the libraries in other Singapore museums actually had their origins here!”4

When custodianship of the art collection was transferred from the National Museum Art Gallery to the Singapore Art Museum (est. 1996) and partially to National Gallery Singapore (est. 2015), materials in the library collection relevant to the Gallery’s focus were also re-allocated accordingly. This included artists’ files containing writeups, articles and biographies relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia modern art collated by curators at Singapore Art Museum, which makes up the beginnings of the archive collection at the Gallery.

What does the Rotunda Library & Archive do?

The primary role of the Rotunda Library & Archive is to support the Gallery’s curatorial vision of presenting and reflexively (re)writing the art histories of Singapore and Southeast Asia, and to examine these art histories in relation to the global history of art. It does so while adhering to the three main principles of librarianship – collecting, preserving and providing access, and the two main principles of archiving – provenance and original order, meaning the order in which the items were arranged when received.

1. Building a collection of historical significance

Over the years, the Rotunda Library & Archive has amassed an extensive collection of books and exhibition catalogues on Southeast Asia modern art, building on the legacies of the libraries at the National Museum Art Gallery and Singapore Art Museum. Priority is given to resources related to artists and artworks in the National Collection. Through donations, partnerships and regular library exchanges with institutions in the region and beyond, the library is able to collect exhibition catalogues that may not be extensively distributed or made readily available to the public. The library also acquires books and rare materials such as prints and photographs as recommended by the curators. These materials are often exhibited alongside artworks to enhance the curatorial narrative.

The Rotunda Library & Archive also actively connects with local and regional artists’ families to seek loans and donations of artists’ archives. These archives often contain valuable first-hand information on the artists’ professional practices, their thoughts and writings, and their views of the world through photographs and sketches. These materials greatly contribute to the study of the artist’s oeuvre, as they provide another dimension beyond the surface of the artwork.

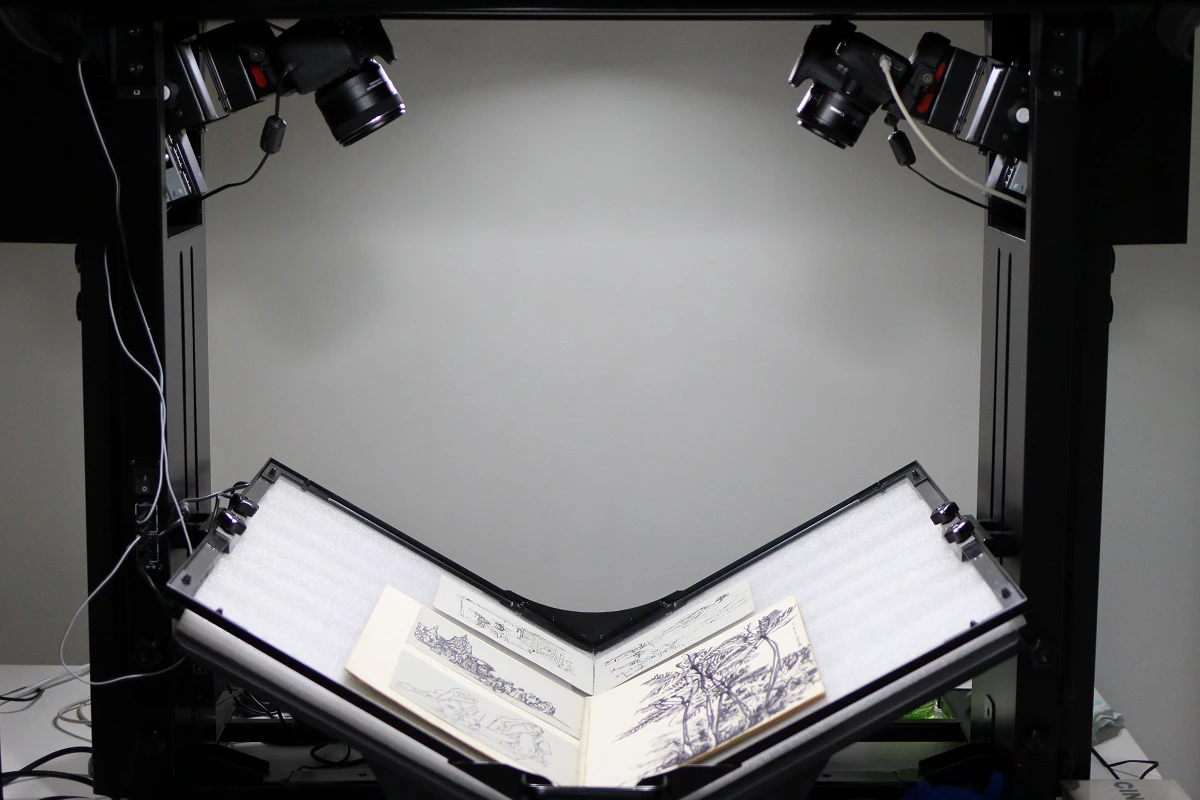

2. Preserving materials to ensure long-term availability

Digitisation is one of the key functions of the Rotunda Library & Archive. Many times, the artist’s archives are loaned to the Rotunda Library & Archive out of goodwill and a common vision to preserve the legacy of the artist, but due to their sentimental value and storage limitations, may not be immediately considered for donation. The Rotunda Library & Archive digitises these materials and keeps the digital copy, while the originals are returned to the family together with a digital copy which also helps the family preserve their archives. Fragile materials in the collection are also digitised and kept in a controlled environment to ensure the originals are kept in good condition.

3. Providing access to support research

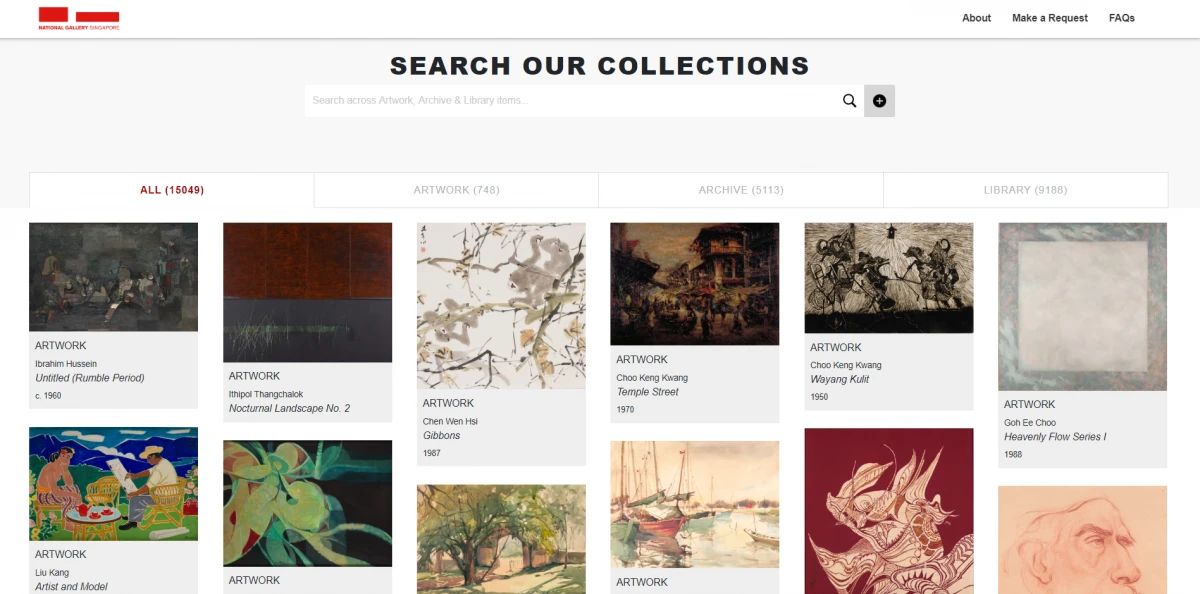

Digitised materials are made available online after clearing of copyrights with the artists’ families and metadata creation, which allows researchers from around the world to access the materials without having to be physically present at the Rotunda Library & Archive.

A collection can only be as good as its catalogue, hence accurate and extensive metadata indexing is essential to ensure efficient searching and establish connections across the artwork, library and archive collections. This includes documenting the provenance, or history of ownership, of items in an archive collection and respecting their original order. This year, the Collections Search Portal was launched together with the opening of the Rotunda Library & Archive, allowing users to search across the three collections of the Gallery. This is only possible with the matching of key metadata such as artists’ names across the collections. As much as possible, content and names of personalities mentioned in the book or document are also added to the metadata to facilitate other searches.

What's in the Rotunda Library & Archive collection?

Items in the Library & Archive often blur the lines between reference material and object. The following are examples where the materiality of the archival items and books is as important as the information contained within, warranting their display as objects in their own right to supplement the Gallery’s exhibitions.

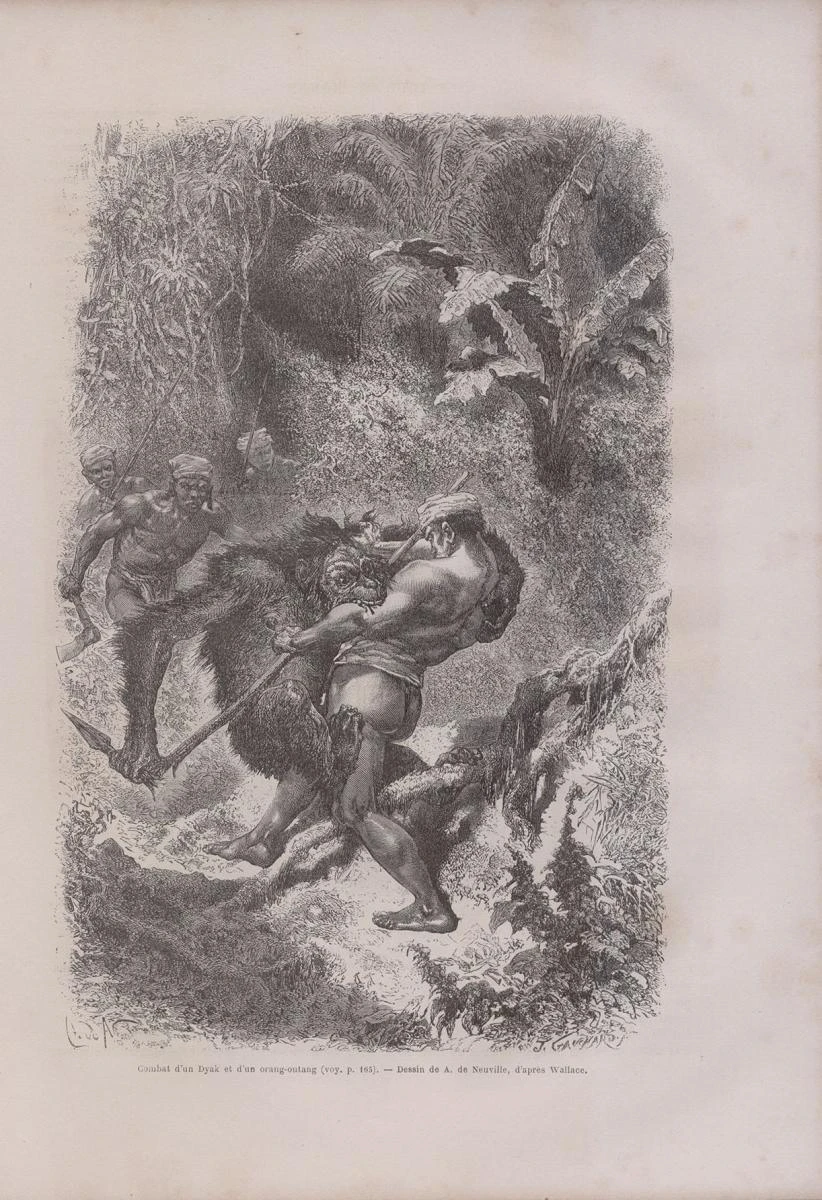

1. 19th– 20th century books and prints documenting Southeast Asia

A collection of 19th and early-20th century rare volumes containing travel accounts, prints and sketches of European explorers from their voyages through the Far East make up some of the oldest materials in the Library & Archive. These prints and drawings show how Singapore and Southeast Asia were represented through the eyes of their colonisers, and served to “educate” the people at home about their colonies, providing important materials for researchers and curators seeking to find ways in unpacking the colonial gaze and power system.

The fantastical imagery recalls Heinrich Leutemann’s print,Unterbrochene Straßenmessung auf Singapore (Interrupted Road Surveying in Singapore), currently on display in Gallery 1 of the DBS Singapore Gallery.

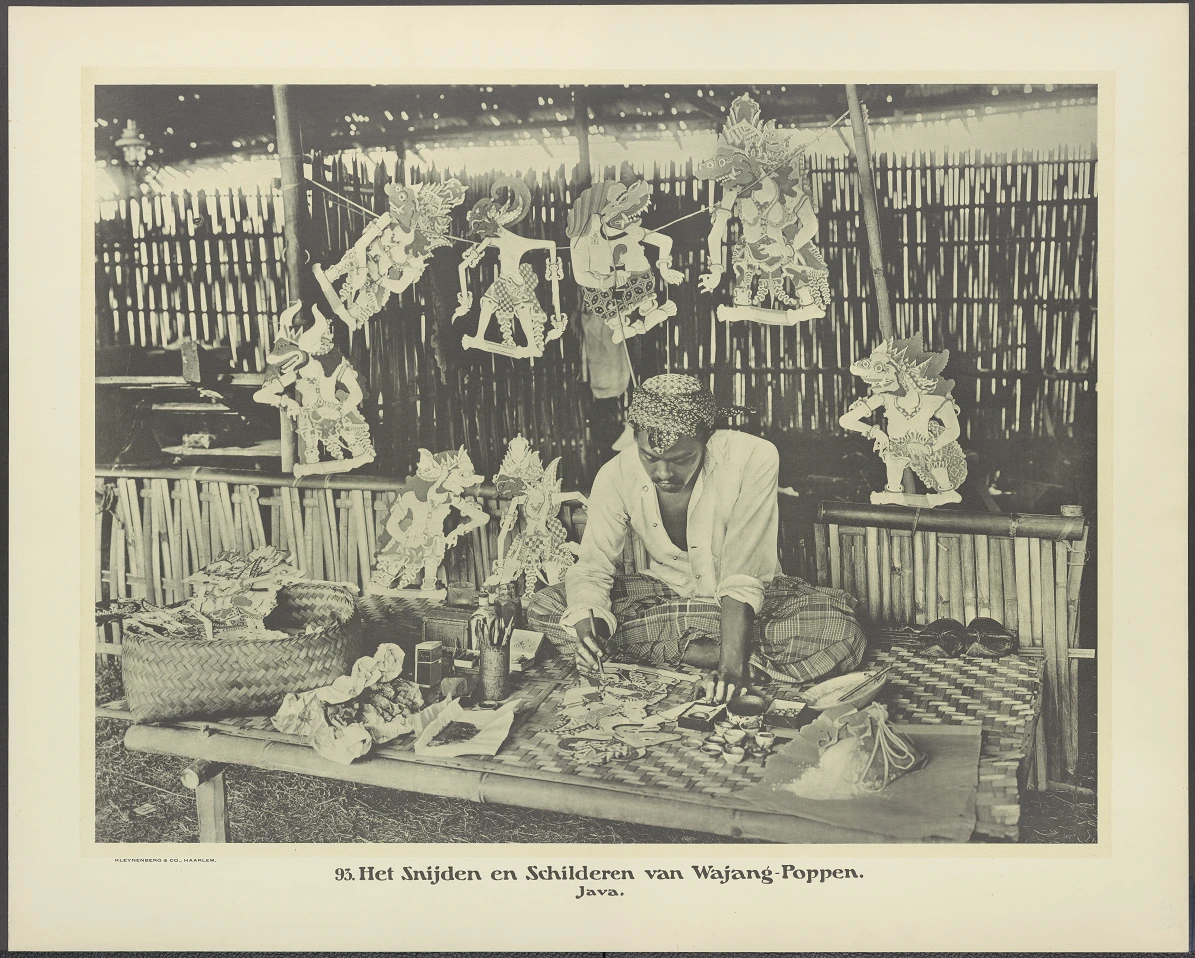

The Kleynenberg prints are some of the largest and heaviest objects in the Library & Archive collection. Measuring 73 by 60 cm, the series consist of 170 photogravure prints and were published in three volumes by Kleynenberg & Co. in Haarlem between 1911 and 1913. They were unique for being the only photographic series printed in large scale and were made specifically to decorate the walls of Dutch schools and teach students about the colonies in the far-flung Indonesian islands. It was commented in the Dutch periodical Neerlandia in 1912:

“Beautifully executed, they give a clear picture of tropical nature, of the various enterprises of natives and Europeans in the Indiës, and of the native and European communities there. Clean, lush landscapes, wild natural foliage, fertile (rice) fields, of the main crops – tea, sugar, rubber, etc – the building and production, the petroleum company at Balikpapan, the state coal company at Sawah Lunto, the tin mining installation at Banka, and many more are expressed so vividly and clearly that we do not hesitate to call the publication a valuable asset for anyone who wants an insight into the life and work in our Indiës, especially for schools. That is, one would like to say that [this is] what has been missing so far to give a good, faithful image of our Indiës.”5

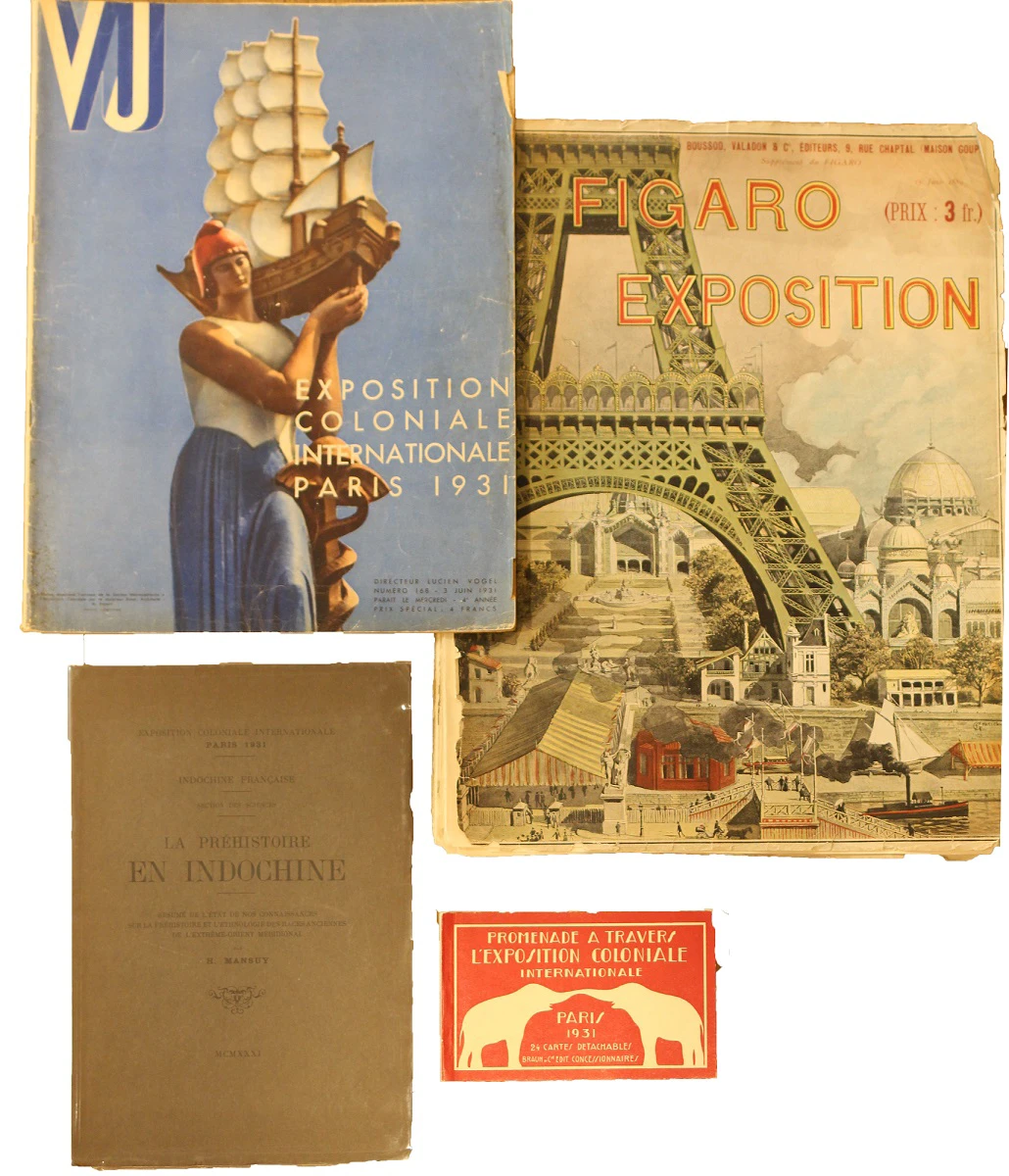

19th century and early-20th century European periodicals and exposition catalogues are another important collection as they helped to showcase Southeast Asian arts, culture and industry to an international audience. These exhibitions were also an opportunity for locals to demonstrate their crafts and skills. For example, the wooden portal at the entrance of the Cambodia pavilion at the 1931 Colonial Exposition in Paris was carved by students of the School of Cambodian Arts at Phnom-Penh.6 These resources are integral for the research of early modern art in Southeast Asia, providing insights into the region’s colonial histories and the subsequent road to decolonisation.

(Top left) VU: Exposition Coloniale Internationale Paris 1931. 3 Juin 1931, Numero 168. RC-RM16.

(Top right) Figaro Exposition, no. 3, 15 Juin 1889. RC-RM11.

(Bottom left) H. Mansuy, Exposition Coloniale Internationale Paris 1931: La Prehistoire en Indochine. RC-RM21.

(Bottom right) Promenade a travers: L'Exposition Coloniale Internationale Paris, 1931. RC-RM41.

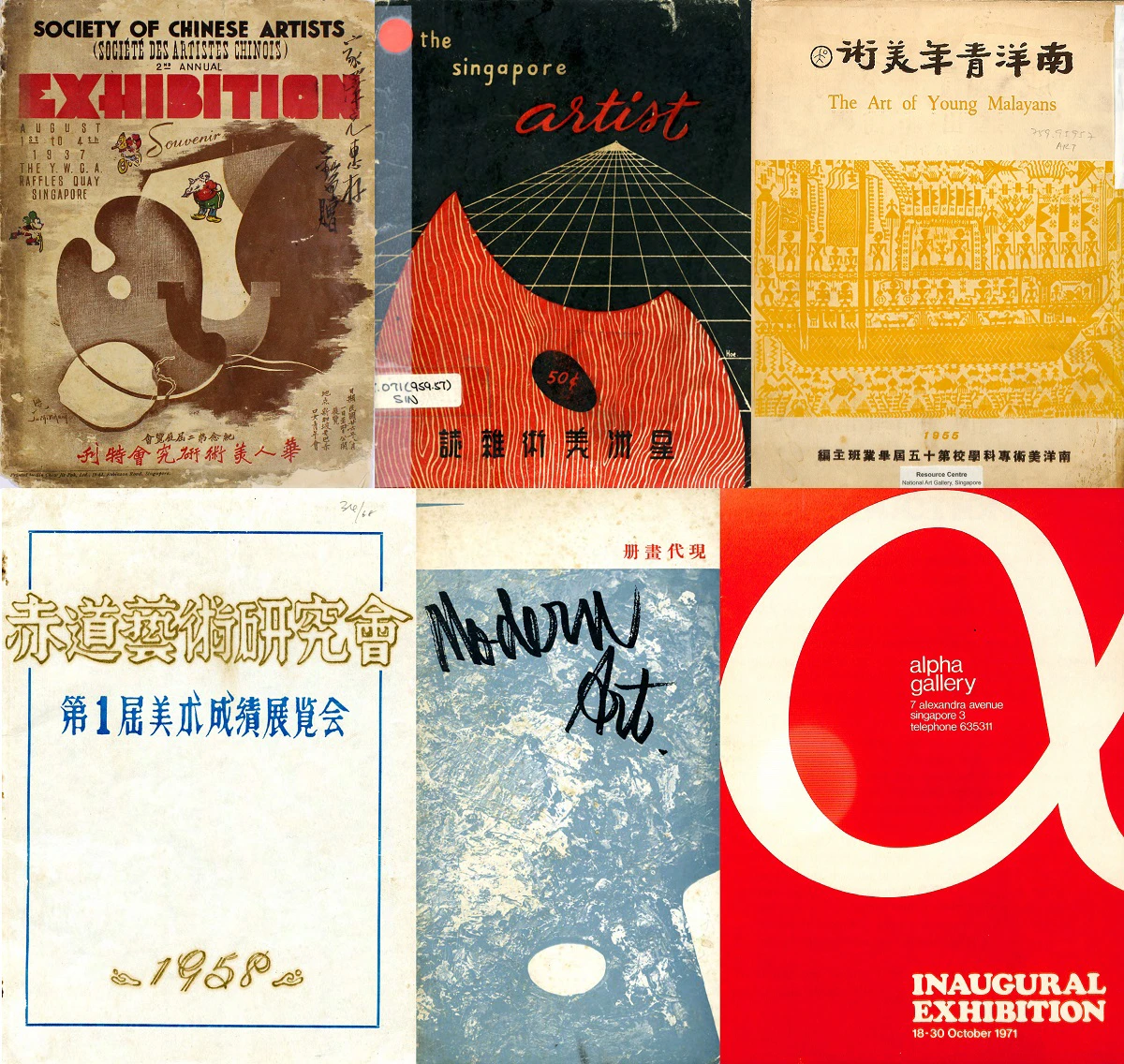

2. 20th century documents and catalogues reflecting the rise of modern art in Southeast Asia

The establishment of the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts in 1938, together with the formation of art societies such as the Society of Chinese Artists (1935) and Singapore Art Society (1949), helped to nurture new generations of artists and oversaw the evolution of artistic trends in Singapore through regular exhibitions. Important reference and archival materials of these art schools, societies, and educators in Singapore can be found in the Rotunda Library & Archive. They should be viewed in tandem with materials from art societies, museums and schools in the region for a better understanding of the development of art in Southeast Asia amidst the socio-political landscape then.

(Top left) Catalogue for the second annual exhibition of the Society of Chinese Artists in 1937. Established in 1935 by graduates of art schools in Shanghai, it was one of the earliest art associations in Singapore. Digitised by National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive with kind permission of Chen Chi Sing @ Tan Chay Lee. RC-S2-CCS2.14-171.

(Top centre) First issue of The Singapore Artist, the multilingual journal of the Singapore Art Society published in 1954. It contained articles on art and the local art scene, written by local artists and art personalities. RC-RM324.

(Top right) Catalogue of the “The Art of Young Malayans” exhibition in 1955, edited by the 15th Graduating Class of Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. It contained essays by artists and teachers at the school such as Lim Hak Tai, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Jen Hao and Liu Kang. RC-RM180.

(Bottom left) Catalogue for the Equator Art Society exhibition in 1958. The Equator Art Society was founded in 1956 and its members were proponents of the social realist art style, which contributed to the nationalistic sentiments of the 1950s and 1960s. 002975.

(Bottom centre) Catalogue of the first Modern Art Society exhibition in 1963. The Modern Art Society sought to move away from past trends such as realism and look at the present and future with a new vision. 002972.

(Bottom right) Catalogue of the inaugural exhibition of the Alpha Gallery in 1971. The Alpha Gallery was established in 1967 and its support for local and international rising artists through regular exhibitions helped to foster an important shift in Singaporean art towards modernism and abstraction. RC-RM179.

(Top left) The Photographic Society of Singapore monthly bulletin, 1/1960. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lim Kwong Ling. 011921.

(Top right) PSS Journal of The Photographic Society of Singapore, No. 1/1978. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lim Kwong Ling. 014602.

(Bottom left) Photo-Art Association of Singapore bulletin, No. 72, Dec 1971. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lim Kwong Ling. 014252.

(Bottom right) Singapore Colour Photographic Association bulletin, Jul 1972. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lim Kwong Ling. 014153.

(Top left) Catalogue of the twelfth national art exhibition, held at the Balai Seni Lukis Negara, 1969. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Dr Ronald and Mrs Susheila McCoy. 013937.

(Top right) Catalogue of Ibrahim Hussein’s artworks, 1969. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Dr Ronald and Mrs Susheila McCoy. 013986.

(Bottom left) A view of modern sculpture in Malaysia by T.K. Sabapathy, 1976. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Dr Ronald and Mrs Susheila McCoy. 013946.

(Bottom right) Catalogue of the premiere exhibition of the Persatuan Pelukis Malaysia (Malaysian Artists Association), 1981, with a message from its first president, Syed Ahmad Jamal, and essay by artist-writer Dr Zakaria Ali. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Dr Ronald and Mrs Susheila McCoy. 014021.

(Left) Contemporary Art in Thailand: effects of modern civilization and influences of Western art, monograph by Professor Bhirasri published in 1960. 011787.

(Right) Catalogue of the XVI National Exhibition of Art, Bangkok: Silpakorn University, 1965. RC-RM64.

Professor Silpa Bhirasri founded the Silpakorn School of Fine Arts in Bangkok in 1933 and served as Dean of the Faculties of Sculpture and Painting when it became a university in 1943. He initiated the annual National Art Exhibition in 1949 to showcase Thai art and artists which continues till today.

From the 1930s, Galo B. Ocampo played a pioneering role amongst Filipino artists in creating art that was modern, indigenous and nationalistic. His 1938 painting Brown Madonna, currently in the collection of University of Santo Tomas Museum in Manila, caused a controversy with the representation of a religious figure as a local, brown-skinned woman in a Filipino environment. The work was exhibited at National Gallery Singapore’s Reframing Modernism exhibition in 2016.

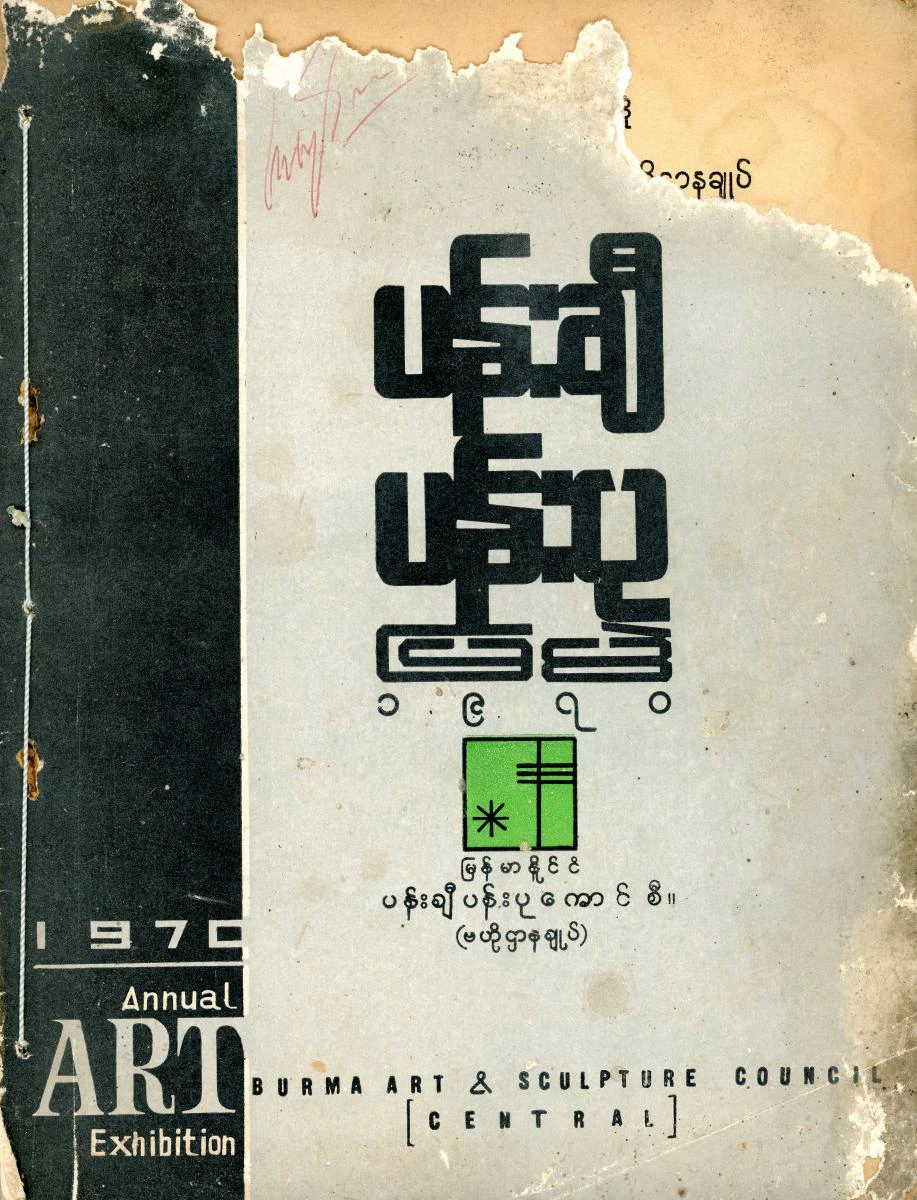

The Council was set up in 1963 under the military regime and its guiding principles were to “preserve and promote culture and uplift patriotic, nationalist and socialist values”.7

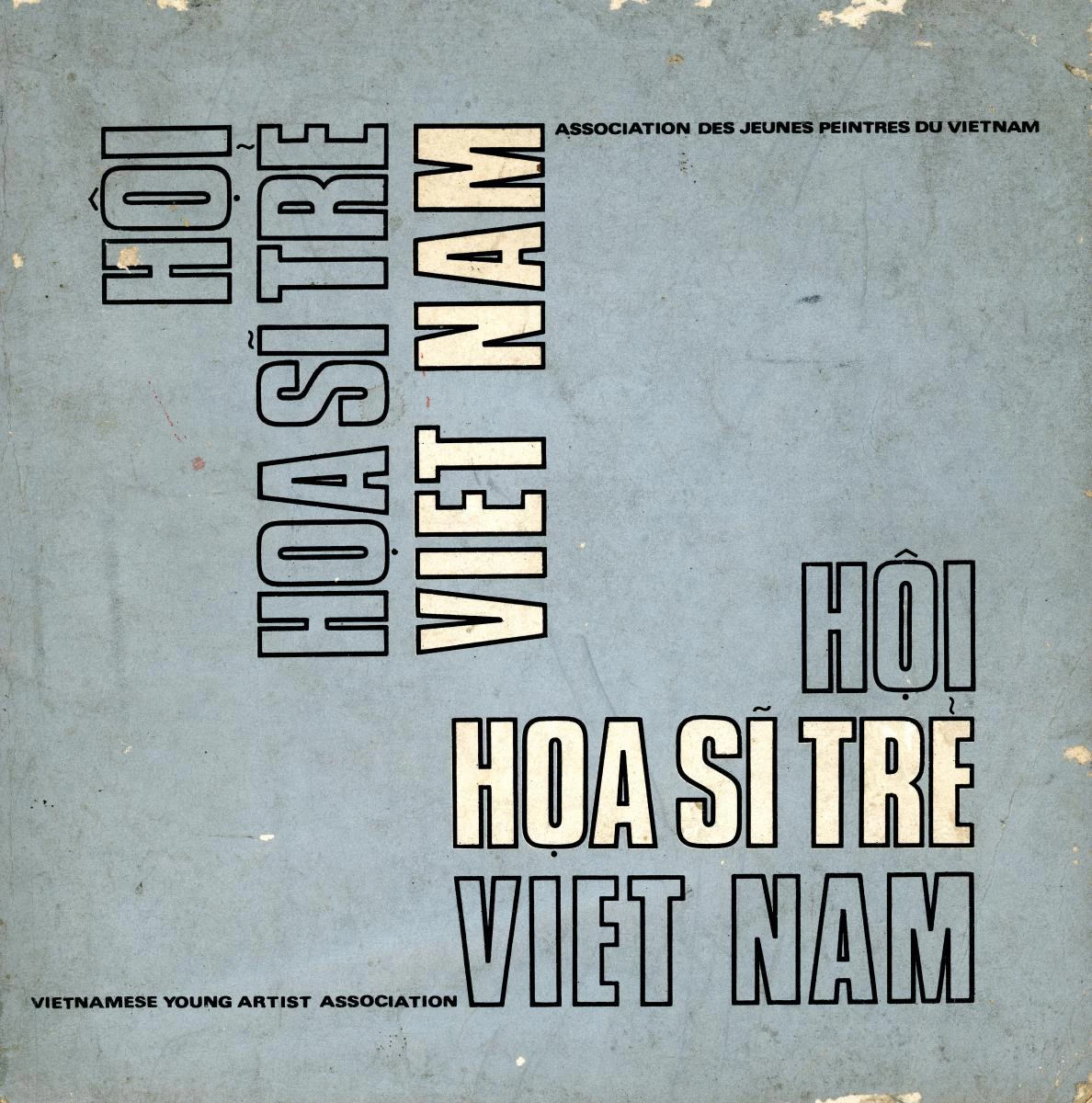

The Association was established in 1966 to promote a progressive art movement where Vietnamese art would respond to the Vietnamese reality and reflect the Vietnamese soul, instead of being caged by European trends.8

3. Artists' Archives

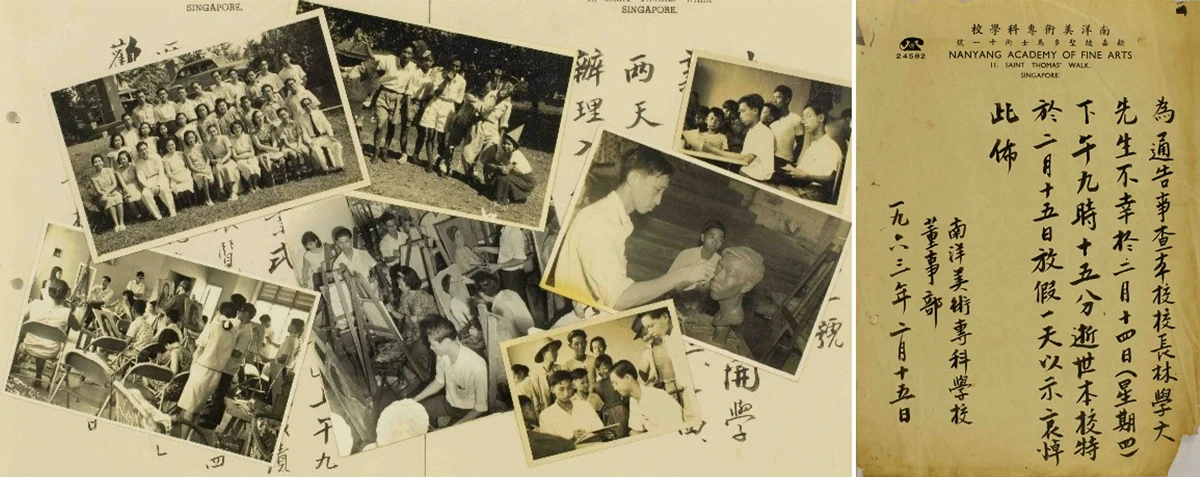

(Left) The Lim Hak Tai & Lim Yew Kuan Archives, containing rare photographs, letters and documents related to their individual artistic practices and teaching careers at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lim Yew Kuan. RC-S67-LHT, RC-S69-LYK.

(Right) Notice from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts board of directors, dated 15 February 1963. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lim Yew Kuan. RC-S67-LHT2.5-198.

Lim Hak Tai, the founding principal of Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, wrote notices in calligraphic script and posted them daily on the school notice board to inform students of upcoming holidays, art lectures and admission matters for a new school term. This particular notice dated 15 February 1963 was poignant for being written by the school’s board of directors instead of in Lim’s own hand, informing students of Lim’s passing and a day of mourning. He was succeeded by his son, Lim Yew Kuan. The Lim Hak Tai & Lim Yew Kuan Archives were generously donated by the Lim family in recognition of the importance of preserving these materials and making them available for research.

(Left) The Georgette Chen Archive is a documentation of Georgette’s artistic and personal life through her voluminous correspondence with friends and colleagues. Containing photographs, letters, diaries and personal artefacts dating from the 1930s to 1980s, they offer a rare and intimate look into her thoughts, observations and life, and provide an understanding of how these shaped her art. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC.

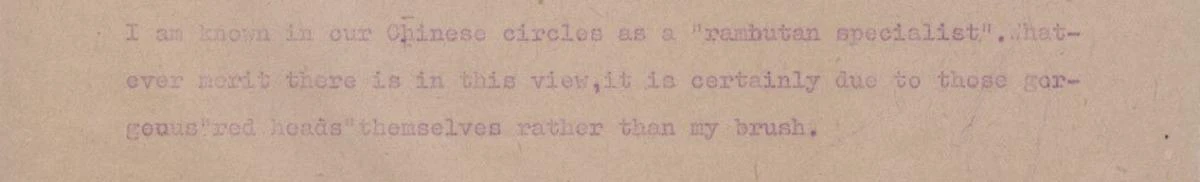

(Right) Georgette Chen painted many paintings of rambutans during her career. At least nine works of still life with rambutans reside in the National Collection. She spoke about her love for rambutans and other tropical fruits in letters to her friends. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation.

Excerpt from Georgette’s letter to Dr. Newton, dated April 14, 1964. Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-03.

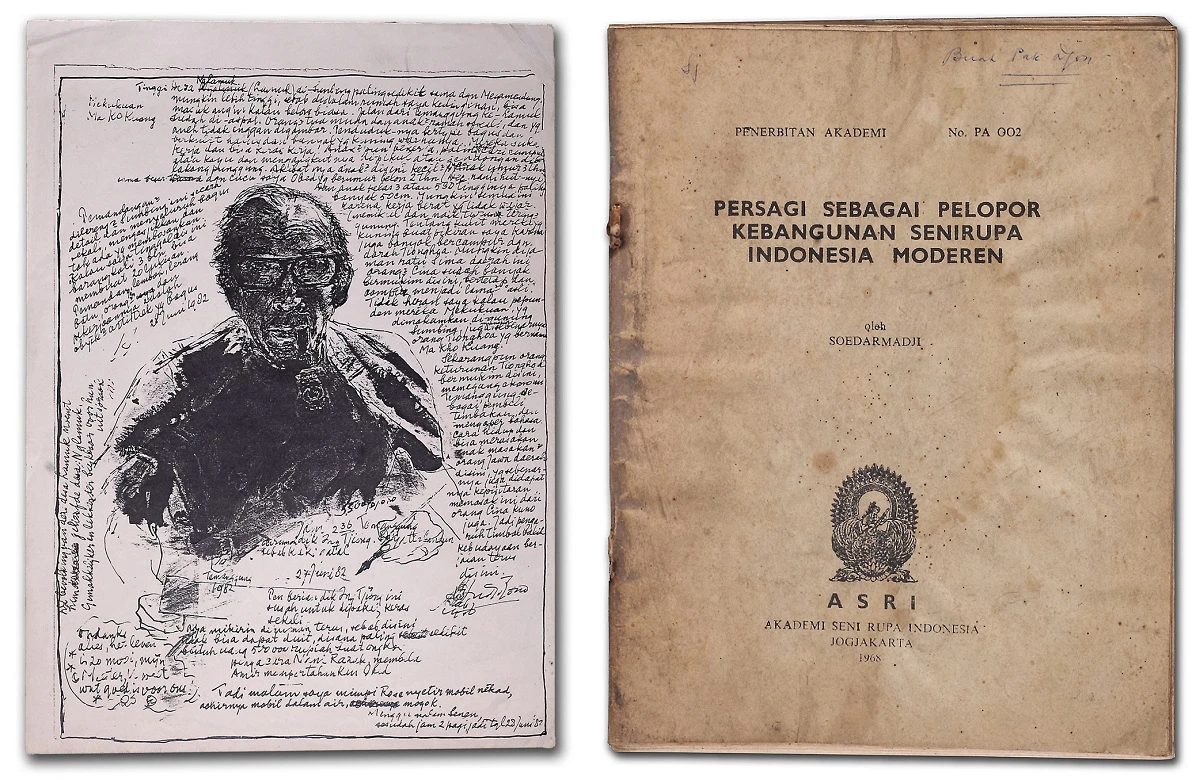

(Right) Art critic Soedarmadji’s 1968 academic paper on PERSAGI as a pioneer in the development of modern Indonesian art. Digitised by National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive with kind permission from Sudjojono Center. RC-I1-SS4-20.

The S. Sudjojono Archive, digitised in partnership with the S. Sudjojono Center in Indonesia, contains a record of his artistic and intellectual processes through his letters, sketches and manuscripts. Sudjojono was a leading figure in modern Indonesian art. He co-founded the Persatuan Ahli-ahli Gambar Indonesia (PERSAGI, or Indonesian Association of Drawing Experts) in 1937 together with fellow artist Agus Djaya, as a rallying call for fellow Indonesian artists to work on an “Indonesian style” that came from one’s own soul. It was a critique against the then dominant “Mooi Indie” (Dutch for “Beautiful Indies”) style that presented a romanticised vision of Indonesia heavily influenced by the Dutch landscape painting tradition

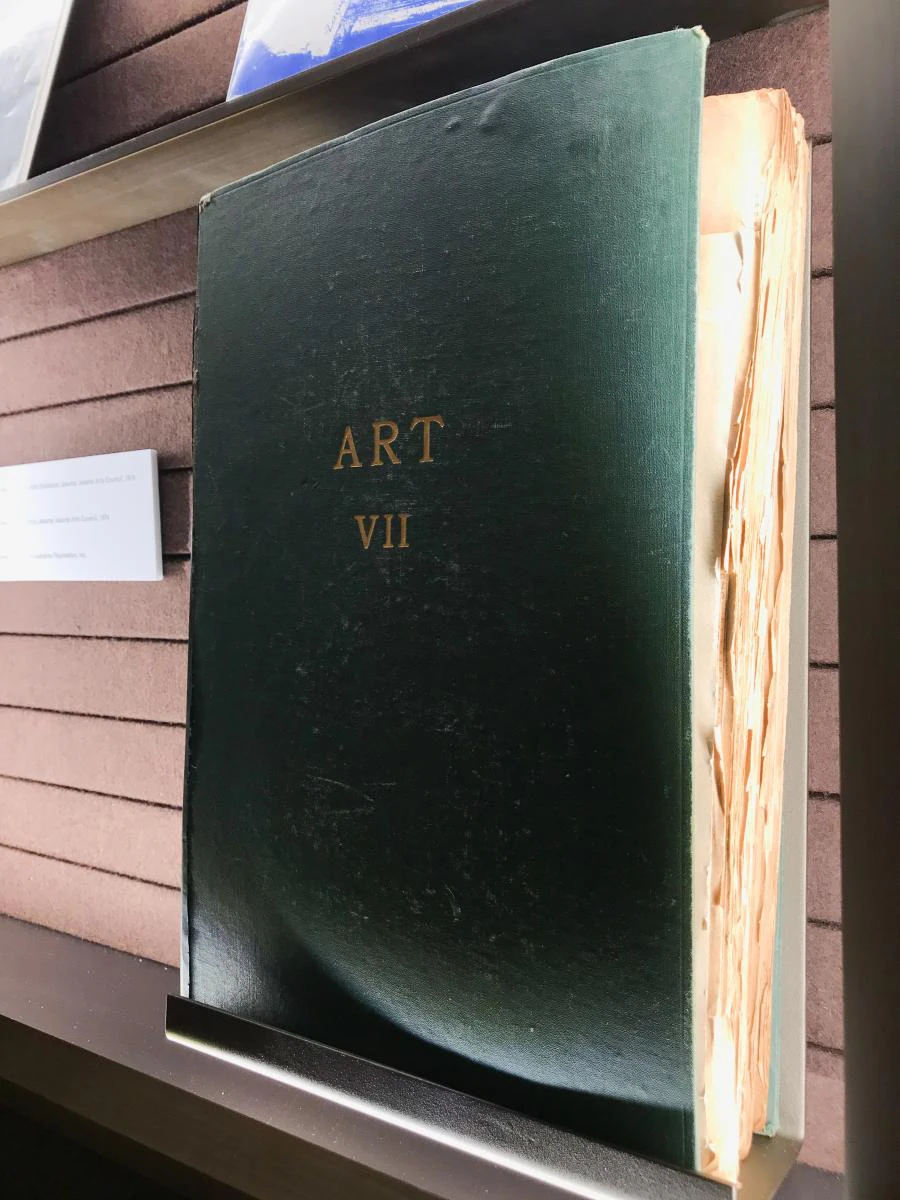

The Purita Kalaw-Ledesma Archive consists of scrapbooks filled with newspaper clippings of art and artists, photographs, letters, invitations and other bits and pieces of ephemera painstakingly collated by Purita Kalaw-Ledesma from 1948 to 2000 in 83 hefty volumes, which tell the story of Philippine art history and the Philippine art world in the 20th century. Beyond the information captured within, the scrapbooks preserve the physical qualities of the various documents stuck on each individual page, and have become in themselves objects of immense archival value. At a time when internet and digital archiving, and a systematic institutional method of archiving the arts were not yet available, these scrapbooks became her way of documenting and collecting art history, as Purissima Benitez-Johannot wrote in a biography of Purita Kalaw-Ledesma published in 2017:

“She filled reams of album paper with news clippings and ephemera, compiling these as a numerically marked hardbound series. Although others wrote the journal pieces that she clipped, Purita conceived, collected, and organized the archives, playing a decisive role in labeling and preserving their contents for posterity."9

Through partnership with the Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation in the Philippines, the Rotunda Library & Archive is fortunate to obtain on loan a digital copy of all the scrapbooks and one of the actual scrapbooks for long-term display.

Documenting the works of a pioneer of performance art in Singapore and Asia, the Lee Wen Archive forms a very important part of Singapore’s art history. The archive comprises documentations, slides, ephemeras and videos of Lee Wen’s early performance art works and his involvement in The Artists Village. The Gallery is a supporting collaborator of the Lee Wen Archive, which was started by the Asia Art Archive in collaboration with the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (for more information on this archive see https://aaa.org.hk/en/collection/search/archive/lee-wen-archive).

Shown here is just a small selection from the Rotunda Library & Archive’s collection of approximately 20,000 physical and digital items. Since the Gallery’s opening in 2015, the Library & Archive has received generous and encouraging support from artists, artists’ families and partner institutions in the region. Tertiary, postgraduate and independent researchers from Singapore and overseas have also used the collection extensively for their coursework, exhibitions and projects, in particular students from the NUS Minor in Art History programme which is co-lectured by Gallery curators and the NTU MA in Museum Studies & Curatorial Practices. By locating the library and archive collection at the heart of the Gallery, the Gallery hopes to encourage more people to realise the wealth of treasures available beyond the artworks and inspire further research into the art histories of the region. To start, please visit the Rotunda Library & Archive or browse the collections online on the Collections Search Portal.

Notes

- Anne Evenhaugen, et al., “State of Art Museum Libraries 2016, ARLIS/NA Museum Division White Paper”, p. 8. https://www.arlisna.org/images/researchreports/State_of_Art_Museum_Libraries_2016.pdf. Accessed on 24 October 2019.

- Jan van der Wateren, “The importance of museum libraries”, Inspel 33(1999)4, pp. 190-198. https://archive.ifla.org/VII/d2/inspel/99-4wajv.pdf. Accessed on 24 October 2019.

- Constance Sheares, National Museum Art Gallery Official Opening 21 August 76, p. [4]. RC-RM334.

- Dome in the City: The Story of the National Museum of Singapore, p. 85. 011706.

- “Platen betreffende Nederlandsch-Indie, in 't bijzonder ten dienste van het onderwijs. (Plates about Dutch-Indies, especially for education)”. Neerlandia. Jaargang 16. Geuze & Co, Dordrecht: 1912. Translated by former Gallery curator Melinda Susanto. https://dbnl.org/tekst/_nee003191201_01/_nee003191201_01_0574.php

- Patricia A. Morton, Hybrid modernities: architecture and representation at the 1931 Colonial Exposition, Paris. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000, p. 38. 011650.

- John B. Glass, PhD thesis. “Burmese painting and graphics in their historical context.” Vol. 2. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, 2009. 005708.

- Hội Họa Sĩ Trẻ Việt Nam: 15 họa sĩ điêu khắc gia, Ho Chi Minh: Hội Họa Sĩ Trẻ Việt Nam, 1973, p. 6.

- Purissima Benitez-Johannot, “An Overview: The Life and Times of Purita Kalaw-Ledesma”, The Life and Times of Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, Quezon City: Vibal Foundation, Inc., 2017., p. 3. 012089.

- Note: As the Collections Search Portal is still growing, some of these materials are not yet online and are not hyperlinked.