Art x War: Art in the Third Indochina War: Paintings by Pech Song

Dr. Roger Nelson focuses on the paintings of the Cambodian artist Pech Song to answer the question “What role have art and artists played during periods of war and conflict implicated in decolonisation as a process?”

What role have art and artists played during periods of war and violent conflict, which in Southeast Asia have often been entwined with processes of decolonisation? In this short article, we address this question while introducing the artist Pech Song (b. 1947, Kandal, Cambodia) and some of his paintings.

These paintings, which were remade in 2019, were originally produced during the early 1980s as models for paintings that were widely reproduced across Cambodia as billboards. The paintings were printed on small, cheap newsprint paper, and one copy was distributed to each province, where a local painter would use it as the model to create a billboard-sized work.

These images are precious records of art and visual culture in Cambodia during the tumultuous aftermath of the Khmer Rouge genocide, which took place between 1975 and1979. During these years, an estimated 80 to 90 per cent of all artists died, and many artworks were lost, dispersed, or destroyed.

About Pech Song

Pech Song holds the unique position of having been commissioned to create paintings used as propaganda by five successive (and opposing) political regimes in Cambodia: first for Sihanouk’s royal government in the late 1960s, then for the US-backed Lon Nol government of the Khmer Republic (1970‒1975), followed by Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge in Democratic Kampuchea (1975‒1979), the Vietnam-backed People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979‒1989), and finally Hun Sen’s post-1990s government. Pech Song’s artistic and political flexibility, seamlessly transitioning from creating art used as propaganda from one regime to the next, is unparalleled in Cambodia’s art history.

Also unparalleled is Pech Song’s ability to capture, in his images, the centrality of art and culture to the Vietnam-backed People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) regime during the 1980s. Unpopular with the population due to its Vietnamese backing and refusal to restore the monarchy, the PRK prioritised the rebuilding of arts and culture above many other social reconstruction efforts in the wake of the Khmer Rouge genocide. Artists, especially performing artists, were among the first groups allowed to return to Phnom Penh after the 1979 overthrow of the Khmer Rouge. This privileging of arts and culture was likely an attempt by the regime to win support and legitimacy.

Artists featured prominently in PRK propaganda during the 1980s, as evidenced in two of these three propaganda paintings. References to Cambodian art of the decades before the Khmer Rouge takeover of 1975, such as visual quotations of the aesthetics popularised by Nhek Dim (1934–1978), for example, were also prominent, as evidenced in one of the paintings discussed in more detail below.

Born to a rural family, Pech Song excelled in artistic skills from a young age and worked as an assistant to the painters of large movie posters that adorned cinemas during the 1960s. He recalls that these painters would wash away the previous poster image in the Mekong River and then repaint a new movie poster on the same canvas.

However, he was forbidden by his parents to study art. In 1965, he stole his birth certificate to change his name from Meas Chann Than, as it was at birth, to Pech Song. He sat the entrance exam for the art school—which in 1965 was transformed from the School of Cambodian Arts to the Royal University of Fine Arts—and was awarded first place in the category of representational drawing/painting.

Because he did not have the support of his family to study, Pech Song struggled to find accommodation during his studies. He solved this problem by playing in a popular music band in Phnom Penh nightclubs, first as a drummer and later as a guitar soloist. “Because of these efforts, I gained much experience about life in the circle of artists,” he remembered in a 1997 account.

In 1970, Pech Song prepared a solo exhibition supported by the French Embassy in Phnom Penh and began receiving commissions for his paintings from the Lon Nol government, which used them as gifts. After 1975, during the Khmer Rouge regime, he survived by painting educational billboards and other materials. After 1979, when the Khmer Rouge was overthrown, he immediately won the support of the new regime, opening a permanent exhibition in Phnom Penh in the early 1980s and making propaganda paintings that were displayed on large billboards in the city and throughout the countryside.

We will now turn our attention to examine some of his paintings from this period.

7 Makara 1979 – 7 Makara 1984 (January 1979 – 7 January 1984), 1983 (remade 2019)

This work was originally produced to commemorate five years since the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge on 7 January 1979, in an effort to garner popular support for the Vietnam-backed People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) regime.

The central group in the painting shows a peasant (with bale of rice in her arms), soldier (with rifle in hand and dressed in uniform), worker (with a wrench in hard and dressed in a hard hat), and artist (with canvas/sketchbook under his arm and dressed in a collared, button-down shirt). The familiar communist triad of worker, peasant and soldier is expanded to include the figure of an artist, explicitly positioning artists as a distinct and integral component of the revolutionary vanguard, in the eyes of the artist, and by extension of the PRK regime.

Further emphasising the importance of arts and culture, a troupe of musicians playing Khmer instruments is seen to the left, dressed in Khmer kraben sampot-trousers.

Monks and laypeople dressed in neat, pleated and collared clothes are depicted among the masses in the background to the right, making clear the PRK’s embrace of urban life, religion and education, all of which had been banned during the Khmer Rouge regime.

7 Makara Maha Jog Jay (7 January Victory Day), c. 1980–1985 (remade 2019)

As in the previous work, this image shows the centrality of arts and culture to the PRK regime.

The principal element in the composition is a musical troupe, playing Khmer instruments and dressed in Khmer attire.

In the background, to the right, is the unmistakeable silhouette of the “Grey Building” apartments, designed by Vann Molyvann and constructed as part of the Bassac Riverfront Complex in the 1960s.

A crowd of cheering masses looks on, including workers and soldiers (identifiable by their uniforms) alongside others dressed in attire that makes them appear distinctly urban and educated.

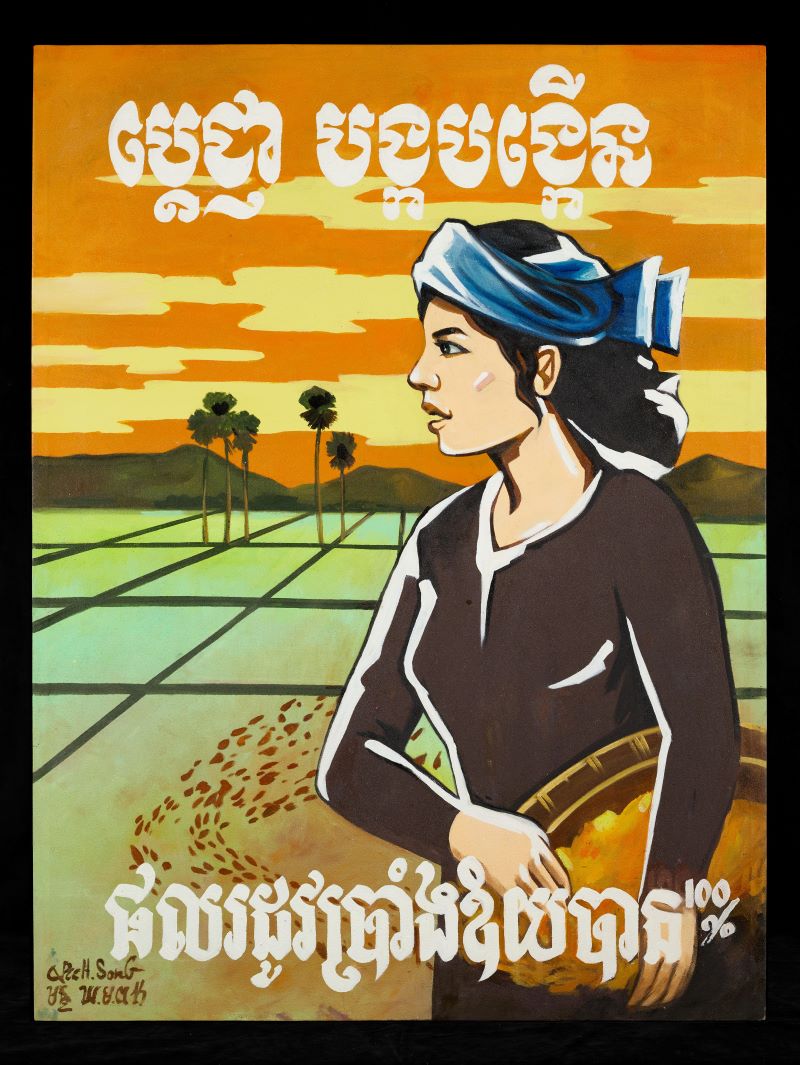

Ptejna Pangka Pangkoen Phal Ratuv Pramng Oy Paan 100% (Commit to Create 100% Harvest During the Dry Season), 1983 (remade 2019)

This work does not depict artists but demonstrates the importance of arts and culture to the PRK regime’s propaganda efforts by visually quoting from the aesthetic tropes of pre-Khmer Rouge Cambodian artworks, such as the landscape paintings popularised by artists like Nhek Dim (1934‒1978).

The prominence of the sugar palm trees, a Cambodian nationalist symbol, is familiar from paintings by artist like Nhek Dim, as are the warm tones and the krama scarf on the woman’s head, identifying her as ethnically Khmer.

Further Reading

Information on Pech Song, including his biography, as well as quotes from the artist recorded in 1997, are from:

Archives on Pech Song, held in the Ingrid Muan Papers, National Museum of Cambodia Library, Phnom Penh.

Additional information on Cambodia’s art-historical context is from:

Ingrid Muan, “Citing Angkor: The ‘Cambodian Arts’ in the Age of Restoration 1918–2000,” unpublished PhD dissertation, Columbia University, New York, 2001.

Additional information on Nhek Dim can be found in:

Roger Nelson, “‘The Work the Nation Depends On’: Landscapes and Women in the Paintings of Nhek Dim,” in Ambitious Alignments: New Histories of Southeast Asian Art, 1945–1990, eds. Stephen H. Whiteman, Sarena Abdullah, Yvonne Low, and Phoebe Scott (Sydney and Singapore: Power Publications and National Gallery Singapore, 2018), 19–48.