Art x War: An Editorial Foreword

Explore new perspectives on modern and contemporary war art from Southeast Asia through this special issue of Perspectives, Art x War. This issue is part of a collaborative research project involving scholars from universities in Australia and Southeast Asia, and curators from National Gallery Singapore and the Australian War Memorial.

The importance of art in depicting war and conflict for a range of state and social functions is well-established in art history and conflict studies.1 Less understood is how artists from Southeast Asia, whose work has been marginalised by the centring of the narratives of imperial and/or allied nations, have responded to war and conflict in the region. Yet artists from the region point to conflicts such as World War II being definitive turning points in development of regional art history. The Filipino Modernist, Fernando Zóbel, famously wrote in the early 1950s that the growth of modern art in the Philippines was directly tied to American GIs stationed in Manila during World War II creating a demand for abstraction.2 In fact, the geopolitical shape of Southeast Asia was defined in the aftermath of that conflict.

The 19th and 20th centuries were marked by enormous conflict in Southeast Asia, often initiated by distant imperial powers intent on resource extraction and geopolitical gain. While depictions of conflict by artists from imperial and colonising centres has been much studied as “war art,” works by artists from those resisting colonisation have been rarely addressed in the same terms.

War art itself can be a fraught category of analysis, based more on theme than adherence to a particular school or style of art. The breadth of works that could fall into this category in the collection of National Gallery Singapore and other collections in the region, demonstrates that there is much we can learn about how people living in Southeast Asia during times of war experienced these conditions—the disruptions to everyday life, the trauma of loss, the exhilaration, fear and exhaustion of combatants and the extraordinarily long sting in the tail of environmental destruction—and how they responded.

Depictions of war and conflict in Southeast Asia have the potential to contribute a great deal to the broader understanding of war art. Moreover, through examining the politics and the aesthetics of war art outside the conventional frameworks established by Euro-American art historical canons, we can advance Southeast Asian art history and make significant interventions to the field of art and conflict globally. Southeast Asia as a regional framework has long been considered a Cold War construct born out of World War II.3 This entanglement between the identification of Southeast Asia as region and the region’s art history is also evident in its museums and collections—an area that bears more research. National Gallery Singapore, with the largest public collection of Southeast Asian art in the world and home to one of the largest Vietnamese war art collections outside of Vietnam, (part of which was donated by the Witness Collection) is a natural place to start.

The essays in this issue of Perspectives are part of a collaborative research project involving scholars from universities in Australia and Southeast Asia, and curators from National Gallery Singapore (NGS) and the Australian War Memorial (AWM). These writers bring a range of expertise to the project, from exhibition-making to military history, from area studies to art history. They provide new perspectives on modern and contemporary war art from Southeast Asia. Perspectives will be publishing work from this project on an iterative basis, with a follow-up issue in September.

This issue brings together the work of curator Elise Routledge from Australian War Memorial (AWM), lead investigator Dr. Elly Kent and art historians Dr. Roger Nelson, Dr. Wulan Dirgantoro and Dr. Margaret Hutchison.

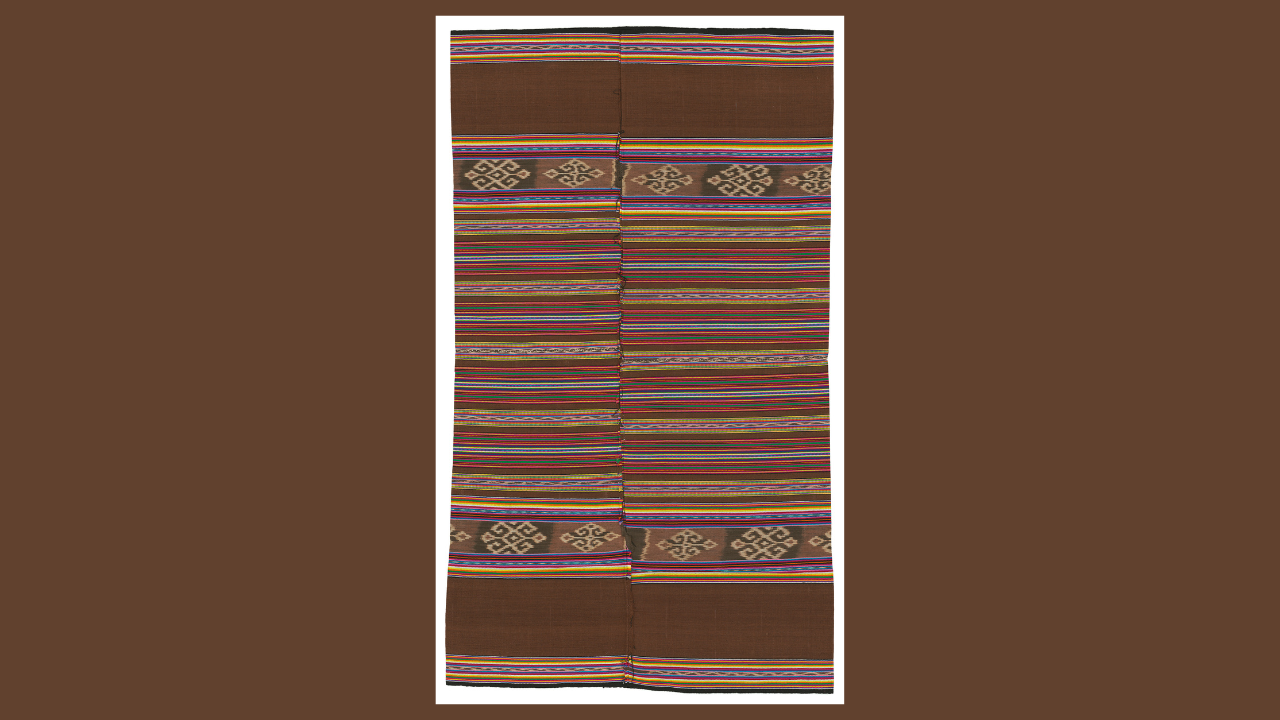

Curator Elise Routledge from AWM discusses the institution’s acquisition of works by artists from Timor-Leste, where centuries of conflict with various occupiers, most recently Indonesia, ultimately resulted in a United Nations supervised vote for independence. This was followed by a period in which United Nations peacekeepers, led by the Australian Defence Force, monitored an uneasy, and often deadly, withdrawal of occupying forces. Routledge describes the genesis and significance of works by the women’s weaving collective Koperativa LO’UD (LO’UD Cooperative) and contemporary artist Maria Madeira, who recently represented Timor-Leste at the Venice Biennale. The stories of women’s resistance and survival are rarely told in war art, but AWM’s acquisition of these works provides an important insight into the significant history shared between Timor-Leste and Australia.

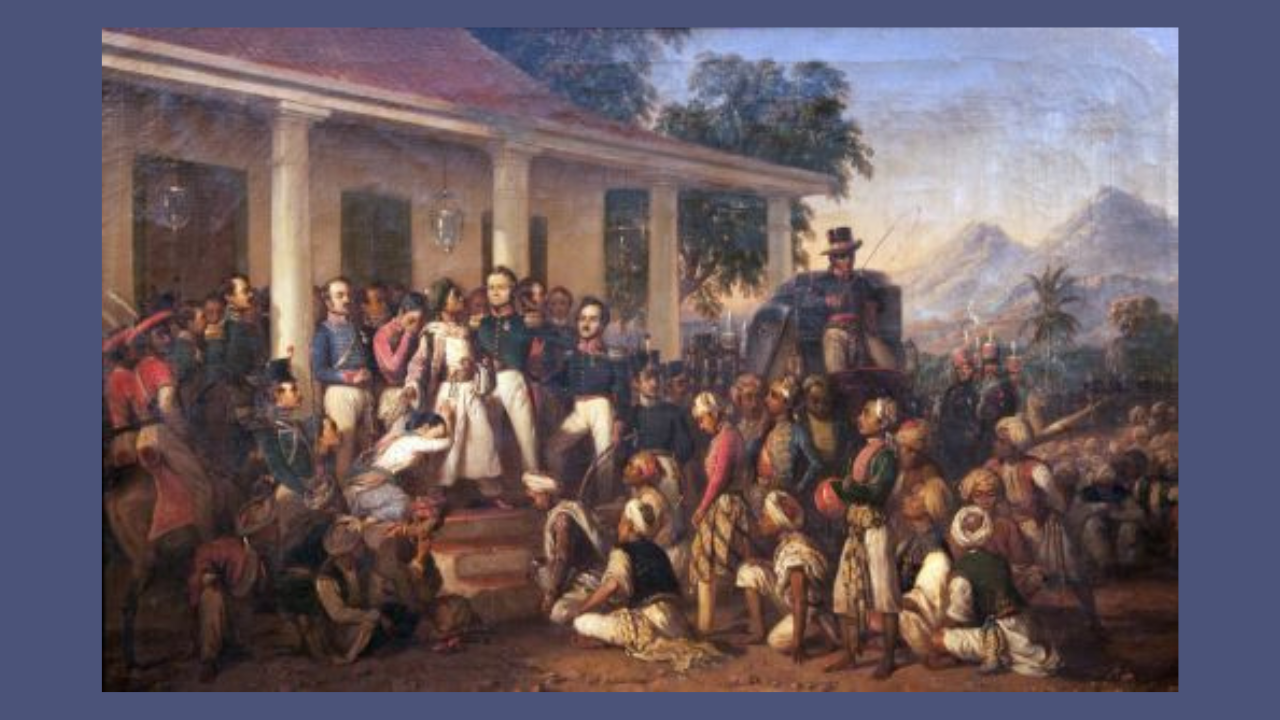

Dr. Elly Kent’s essay discusses the ongoing fascination of artists and scholars alike with the enormous history painting, Penangkapan Pangeran Diponegoro (The Arrest of Prince Diponegoro) (1857) by Javanese painter, Raden Saleh (1811–1880). She explores both the changing social import of this image over time, and just a few of the many artworks that have appropriated or responded to it during Indonesia’s tumultuous 20th and 21st centuries. The essay also looks back to the artist’s biography, and the resonances between his “proto-nationalist” painting and other revolutionary artworks depicting those who resist imperial powers, most significantly Goya’s The Third of May 1808 (1814).

Dr. Wulan Dirgantoro reviews and compares two books, one recent and one published in 1982, that address the work and life of the artist Dullah. The first book, Dullah: Karya dalam Peperangan dan Revolusi (Dullah: Paintings in War and Revolution, 1982) features a folio of paintings which are, paradoxically, painted not by Dullah, but by his painting students, who ranged in age from 11 to 15. Abdulbari’s Melukis di Tengah Perang (2023) is, as Dirgantoro suggests, a historical account rather than an art historical study, which looks at the broader context of Dullah’s work and his efforts to document the nation’s achievements.

Dr. Roger Nelson focuses on the paintings of the Cambodian artist Pech Song to answer the question “What role have art and artists played during periods of war and conflict implicated in decolonisation as a process?” Pech Song was commissioned by five successive (and opposing) political regimes in Cambodia. Nelson highlights how Pech Song’s work provides a unique and important perspective on artistic and cultural production for the Vietnam-backed People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) (1979–1989), in turn pointing to the complicated dialectic between art and propaganda during the longue durée of nation building in Southeast Asia in the 20th century.

Finally, Dr. Margaret Hutchison’s essay introduces readers to the broader field of scholarship around war art: its history, role and parameters in Euro-American art historical canons and the emerging discourses that are disrupting these centring tendencies. As a leading expert on Australia’s official war art scheme, she also provides an important analysis of the origins and changing nature of war art in the Australian War Memorial, and particularly in relation to art made in and about conflicts in Southeast Asia. As we see in Elise Routledge’s article, the AWM is working with Southeast Asian artists in Australia and the region to ensure their perspectives are represented in Australia’s largest collection of war art. Projects such as this one, and others like it, are therefore important lenses we can use, to borrow Dr. Hutchison words, “to not only reflect on a shared history of conflict but also to interpret memories of the war anew.”

Subsequent issues of Perspectives will showcase ongoing research that comes out of this collaboration, extending on the framework set up by this special issue that oscillates between modern art, contemporary art and their discursive representation of historic conflicts that stretch across regions and time periods. In turn, this will continue to highlight significant research being undertaken in the region to consider how “art,” “war” and “war art” continue to influence how we think about “Southeast Asia” in the world today.

Notes

1. Margaret Hutchison, Painting War: A History of Australia’s First World War Art Scheme (Cambridge University Press, 2018); Anthea Gunn and Laura Webster, “WAR (ART): What is it good for?” in The Politics of Artists in War Zones: Art in Conflict, eds. Kit Messaham-Muir, Uroš Cvoro and Monika Lukowska-Appel (Bloomsbury, 2023).

2. Fernando Zóbel, “Art in the Philippines Today,” 1953, RC-PH04-PKL.01.05-0160. This archive was loaned by Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc. to National Gallery Singapore Resource Centre for digitisation in 2014

3. Benedict Anderson, The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia and the World (Verso, 1998).