Art x War: Representing Conflict in SEA: Australia's Official War Art Collection

Dr. Margaret Hutchison’s essay provides an important analysis of the origins and changing nature of war art in the Australian War Memorial, and particularly in relation to art made in and about conflicts in Southeast Asia.

War and art have a longstanding relationship. Art has been used to promote, celebrate, condemn and protest conflict for centuries. Yet, “war art” is difficult to categorise, often defined more by its content rather than its style. Scholars working within the Euro-American art historical canons have evaluated war art and artists for their role as witnesses to conflict. Indeed, there is often an inherent hierarchy in this witnessing, with the authenticity of the combatant artist often seen as more worthy, more “authentic,” than representations by those who were not physically there.1 War art, in this sense, encompasses both personal and commissioned responses to conflict, with little distinction between aesthetically significant artworks and pieces that are more pedestrian in their depictions of war yet remain in institutional collections because of their subject matter.

Such visual representations of conflict often draw on established narratives circulating within a culture, be they ones of celebration or resistance. Artists have long used visual templates to frame or reframe the conflict they are representing within inherited visual traditions. But such templates can also be repurposed. It is therefore essential to understand the narrative an artist decides to adopt and for what reason. While art can construct or reconstruct dominant narratives of war, it can also question or unsettle them. As Timothy Ashplant, Graham Dawson and Michael Roper argue,

Even while artistic media may seem to be operating within terms of conventional public fictions, they may still create spaces for the representation of otherwise hidden dimensions.2

Moreover, the meanings derived from or imposed on war art shift over time and space to suit the needs of a particular generation or historical/political context.

Australia has a tradition of commissioning official war artists dating back to the First World War. Examining the genesis of this enduring commemorative practice is significant to understand the role art has played in the way Australians interpret and remember their nation’s participation in conflict. In the context of the theme of this issue of Perspectives, it is important for understanding how official war art has framed Australia’s involvement in conflicts in Southeast Asia.

Origins of Australia’s official war art scheme

Ideas for an Australian art scheme emerged during 1916. Proposals put forward by Will Dyson, an expatriate cartoonist living and working in London, and Charles Bean, Australia’s official war correspondent and later historian, significantly influenced the shape and character of Australia’s official collection. Both proposals, for instance, stressed the importance of the role of artists as witnesses to war. In his letter to Andrew Fisher, Australia’s High Commissioner in London, Dyson volunteered to go to the Western Front stating:

[…] that it would be of interest to the people of Australia of today and in the future to see sketches illustrating the relationship of the Australians to the war and interpreting the feelings and character of the Australian troops in France.3

Bean too saw the value of art created in proximity to the battlefield. His ideas stemmed from his role as editor of The Anzac Book, a collection of satirical sketches and writings by Australian troops at Gallipoli.4 He envisioned a collection of artworks that would preserve an Australian experience of war, and which would be housed in a future national war museum, now the Australian War Memorial (AWM).

Dyson’s and Bean’s proposals ushered in an official art scheme that focused almost exclusively on the battlefield and emphasised the role of the artist as an eyewitness to conflict. This established a collection that privileged military themes, at the cost of Australia’s war experience beyond the battlefield. Such characteristics have persisted into the contemporary era. Official artists commissioned to capture 21st-century conflicts, such as Lyndell Brown and Charles Green, have noted how conscious they were of the legacy and tradition of Australia’s official war art when they took up their commissions in 2007. For Brown and Green, this legacy informed their interpretation of conflict. They took their role as witnesses seriously and painted only what they observed of the Australian Defence Force in Iraq and Afghanistan, drawing on an academic realist style of painting that echoed that used by official artists, such as George Lambert, to capture World War I.

Art and conflict in SEA

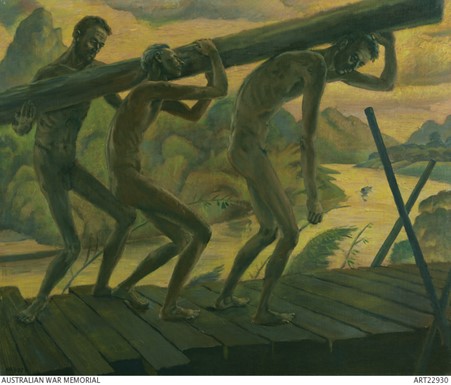

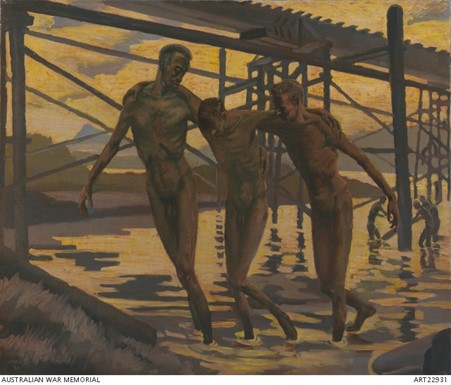

The practices established in the First World War have shaped how Australia’s participation in conflicts across Southeast Asia has been framed in the official collection. During the Second World War, 35 artists were commissioned. The work of Murray Griffin, an official artist who became a prisoner of the Japanese in Singapore, is an important record of the prisoner of war (POW) experience. His delicate and sensitive sketches portray and bear witness to the horror of life at Changi prisoner-of-war camp where he was imprisoned during the war. Most official artists focused on the Australian experience of the conflict rather than exploring the broader, complex colonial contexts in which troops were fighting. For instance, there is Harold Abbot, who was appointed as an official artist for Australia in 1943. His work reflects on the experience of Australian troops after the Fall of Singapore. A triptych of suffering, from 1946, captures the POW experience on the Thai-Burma Railway. These images, especially On the Thailand Railway, are powerful representations of the suffering of these men, depicting emaciated figures within an oppressive landscape.

The official art of the world wars and their aftermaths sought to record and interpret Australian experiences of war. However, this did not translate well into the era of the war in Vietnam. Only two official artists were commissioned by the Australian government to capture this conflict: Bruce Fletcher and Ken McFadyen. Together, these artists produced around 300 images of Australian troops in Vietnam, as well as commemorative canvases of key moments of combat, such as Fletcher’s 1970 painting entitled Long Tan action, Vietnam, 18 August 1966. Both Fletcher and McFadyen worked in a realist style and took their role as witnesses to war literally. Yet, the artistic conventions that had dominated Australia’s official war art since World War I rang hollow during this conflict. To some extent, official war art fell out of favour in this period, and it was unofficial art and photographs that protested the war that took precedence in shaping the narrative of this conflict. While photography had been used in both world wars, its enhanced versatility in this era made it a prime medium in which to document the transitory moments of the conflict and unofficial art expressed the immediacy and horror of the war, capturing the anti-war sentiment of the 1960s and 70s and providing a marked contrast to images produced as part of the official art scheme.5

Witnessing history

In the last decade or so, war art has begun to shift beyond the role of bearing witness to conflict. Works produced through a recent collaboration between the AWM and National of Museum of Singapore (NMS) explore what June Yap has termed the “historiographical aesthetic” of art, which brings to light “histories variously neglected, suppressed, suspended and left behind.”6 The AWM and NMS partnership supported artists-in-residence Debbie Ding and Angela Tiatia, who both produced works that engaged with how World War II has been preserved and remembered in Australia and Singapore, made connections across borders and between past and present. Ding’s War Fronts, a series of digital holograms, looks specifically at the landscape of war, portraying significant battle sites in Singapore that ask the viewer to “search the Singaporean landscape for traces of history that cannot be seen or observed.”7 Tiatia’s work, a film entitled The Fall, was inspired by written and oral accounts of individuals who experienced the Fall of Singapore. Her work reflects on the difference between grand historical narratives and intimate personal ones, making perceptible the complexities of history and the aftershocks of memory. Such artworks present an opportunity to not only reflect on a shared history of conflict but also to interpret memories of the war anew.

Conclusion

Understanding the origins and history of Australia’s official war art scheme affords us an insight into the politics of war art as a site of social remembering. In recent decades, there has been a redefining of Australia’s official war art tradition. The AWM’s art collection now includes a range of voices and perspectives on war and looks beyond the battlefield to consider the enduring costs of conflict. While the collection remains largely nationally focused—due to the World War I legacy of official representations presenting the conflict as a national experience—recent commissions and acquisitions have begun to move beyond this framework, as seen in Ding’s and Tiatia’s work. This has resulted in artworks that not only unsettle nationally focused narratives but also reflect on the complex colonial contexts within which these wars occurred. Such works also reframe concepts of war art as sites of memory, revealing that war art is as much about making history as it is about witnessing it.

Notes

1. Joanna Bourke, ed., War and Art: A Visual History of Modern Conflict, Illustrated edition (Reaktion Books, 2017), 7–15.

2. Timothy G. Ashplant, Graham Dawson and Michael Roper, eds., Commemorating War: The Politics of Memory, (Transaction Publishers, 2009), 36–37.

3. Will Dyson to Andrew Fisher, 23 August 1916, AWM93 18/7/5 Part 1.

4. Will Dyson to Andrew Fisher, 23 August 1916, AWM93 18/7/5 Part 1.

5. Sam Bowker, “Images for Dead Men: Australian Artists after the Vietnam War,” in War and Art (Brill Schöningh, 2020), 285–86.

6. June Yap, Retrospective: A Historiographical Aesthetic in Contemporary Singapore and Malaysia (Lexington Books, 2017), 273.

7. Debbie Ding, “War Fronts,” After the Fall (National Museum of Singapore, 2017).