Art x War: Painting the Revolution: Child Artists in Indonesia’s War of Independence—A Review of Two Books

Dr. Wulan Dirgantoro reviews and compares two books, one recent and one published in 1982, that address the work and life of the artist Dullah.

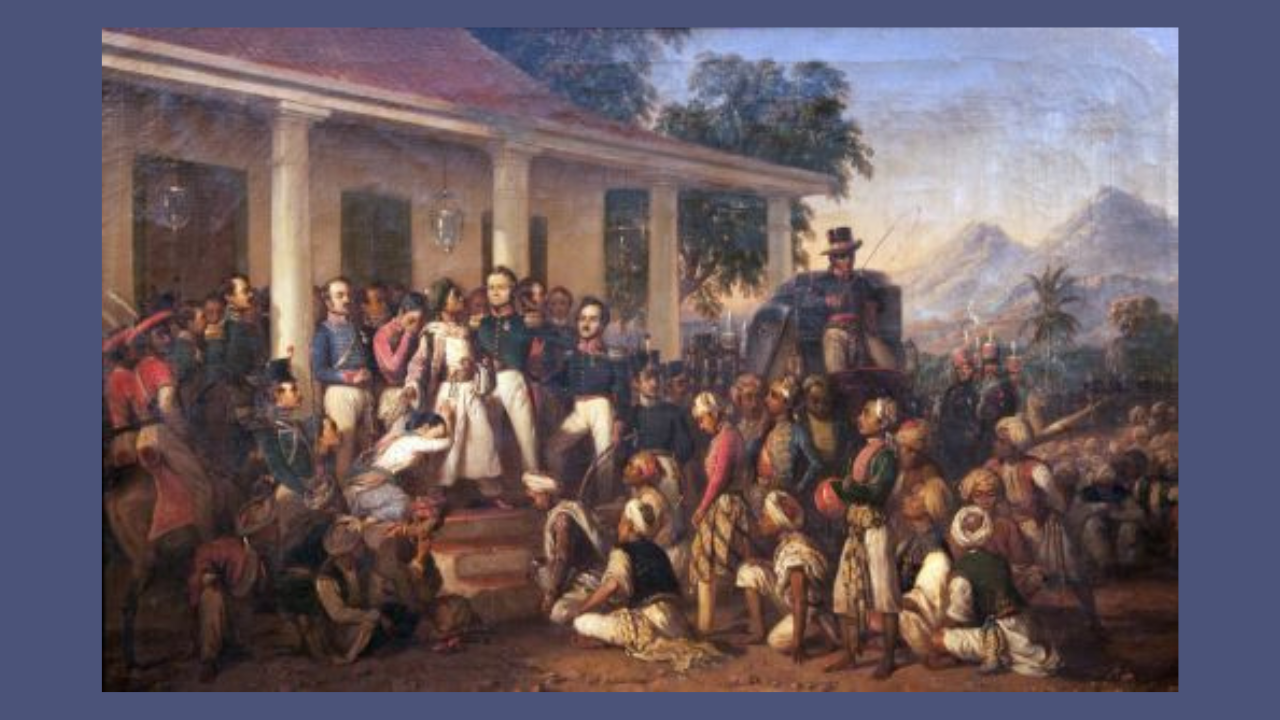

War and conflict profoundly affect society and leave lasting scars that extend to artists and their communities. During postcolonial struggles, it became almost imperative for artists to produce artworks that supported their causes or document the conflicts for the future. The latter is the drive behind the 1982 folio book Dullah: Karya dalam Peperangan dan Revolusi (Dullah: Paintings in War and Revolution), published by Balai Pustaka in 1982. Dullah (1919‒1996) was an Indonesian war artist who actively documented the revolutionary period (1945‒1950). A close confidante of Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, Dullah was eventually entrusted with the task of curating the first president’s art collection that will eventually become the Presidential collection.1 The publication documents a 1978 exhibition and contains colour reproductions of 84 paintings from the show.

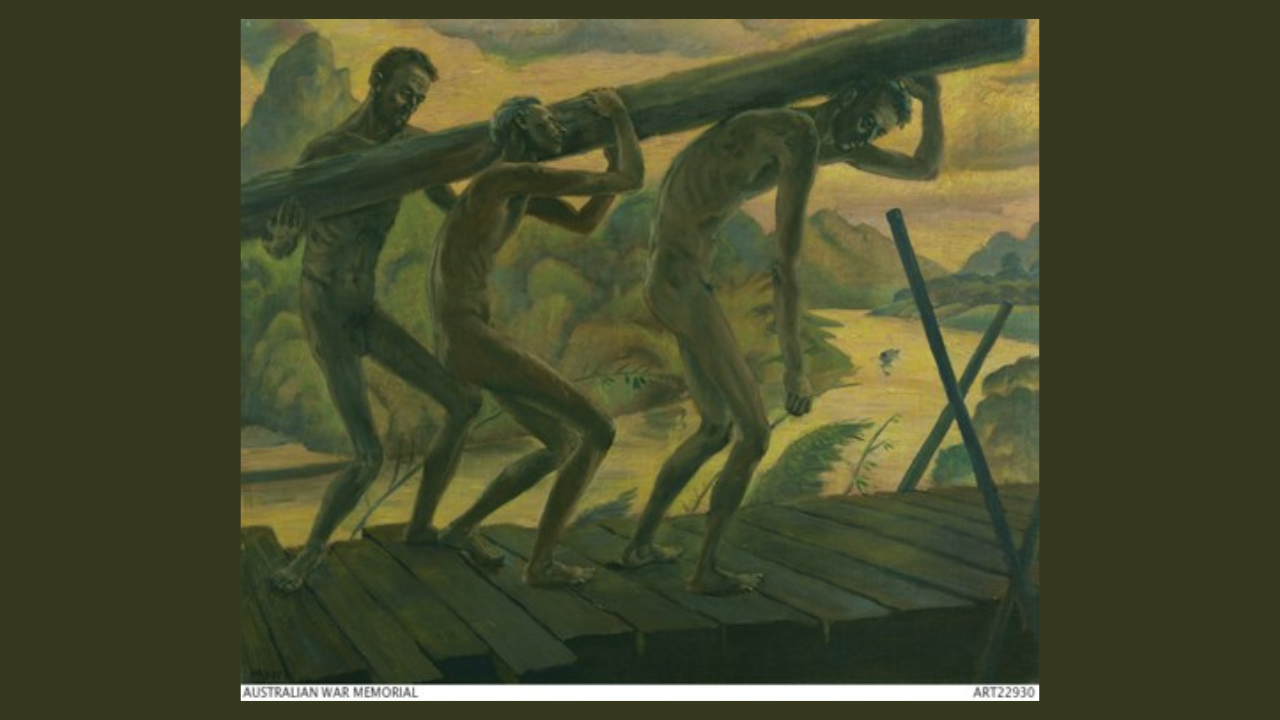

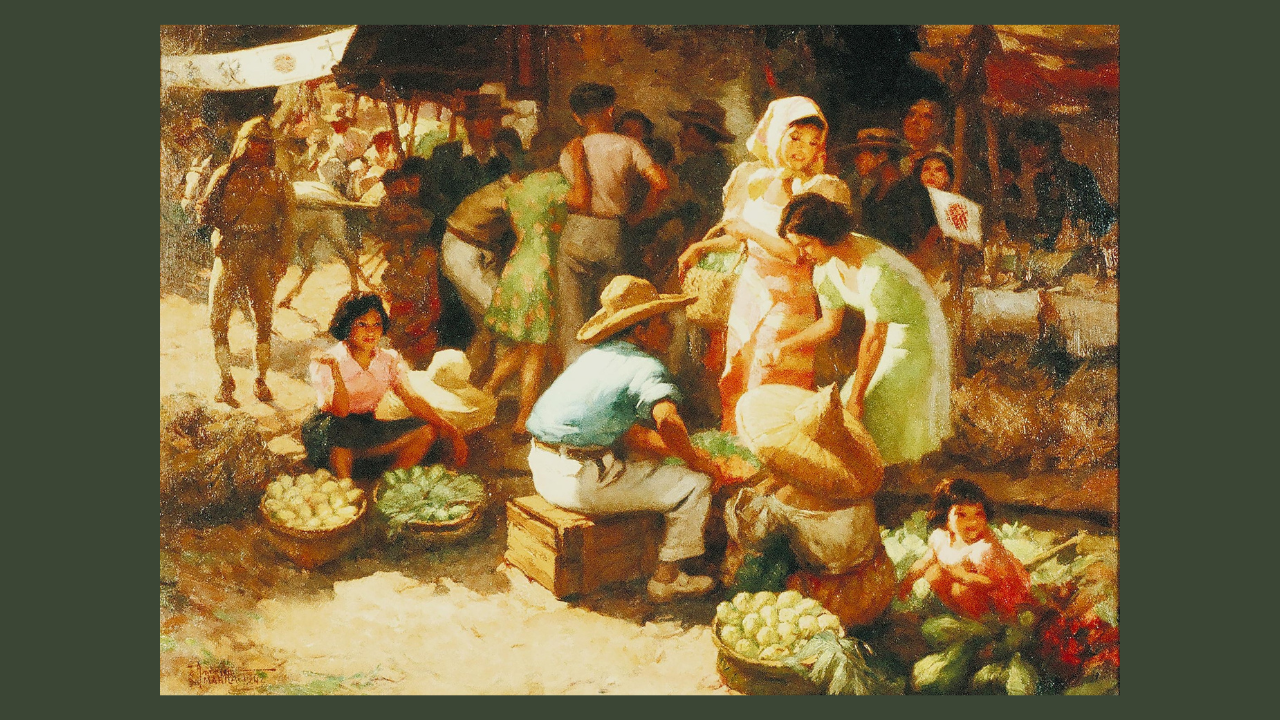

Yet the paintings discussed in the book were not Dullah’s. Instead, they were by Dullah’s students: Mohammad Toha (11 years old), Muhammad Affandi (12 years old), FX Soepono (15 years old), Sri Suwarno (14 years old) and Sarjito (14 years old). With some of the artists barely in their teens, they were on the front line documenting fighting that took place during the second Dutch aggression in Yogyakarta between 1948 and 1949. Supplied with basic art materials and strong encouragement from their teacher, the children witnessed and painted plein-air depictions of historical events, such as the aerial bombing of Yogya, Dutch soldiers’ violence on civilians, and the moments when the Dutch military exiled Sukarno and Hatta. Their works captured these events. In the words of the renowned Indonesian painter, Affandi, as quoted in the publication,

As the product of innocent children these paintings are even more realistic than a photo of the same theme. A photographer would perhaps not have the courage to make photos of Dutch soldiers shooting at local inhabitants.2

Yet, as scholars who research visual culture would be aware, images have a long tradition of both documenting and distorting the facts. Of what use, then, are images to historians? What types of historical evidence do images provide? Abdulbari’s Melukis di Tengah Perang grapples with these questions by thoroughly examining some of the paintings made by Dullah’s students. Unlike Dullah’s book, Melukis is not an art history text; it is a history book that investigates the use of images as a historical source. Abdulbari carefully explains that historians should consider non-textual sources, factual and historical, equal to textual sources commonly used by historians.3

Melukis di Tengah Perang fills the gaps in our knowledge about this period in Indonesian art history. Indonesian art history tends to gloss over this period, focusing instead on nationalistic representation of the conflict, often gleaned from direct observation. Examples include Sudjojono’s Seko 1 ( Guerilla Patrol, 1949) and Affandi’s Mata-mata Musuh (The Enemy Spy, 1947), as well as later, post-facto ones such as Hendra Gunawan’s Pengantin Revolusi (Bride and Groom of the Revolution, 1955). Yet few have examined what it means for artists to be in a conflict zone. Abdulbari astutely notes that Dullah was uncertain whether to depict the “heroism of the revolution or stay true to Persagi’s realism…[T]hat revolution is not only heroic events but there is also the reality of the ordinary people.”4 Dullah’s anxiety is, in a way, common to many artists when they situate their role as eyewitnesses in conflict. Activating the images during an ongoing conflict through painting arousing slogans and posters to raise political consciousness for ordinary people, rather than after the fact, is arguably more effective.

In Melukis di Tengah Perang, Abdulbari observes that Dullah was driven by his passion for dokoementasi nasional (national documentation)—to record the nation's historical achievements between 1962‒1963. Another factor that contributed to this drive was that he was not in Jakarta to witness Indonesia’s proclamation of independence in August 1945. Importantly, Dullah also lost the sketches and paintings he collected from his students, as well as his own, during the Dutch aggression in 1948.5 Prompted by this and determined not to miss out on more, Dullah asked his young students to document the front line, believing that their age would protect them from the suspicion of the Dutch army.

Melukis di Tengah Perang thus complements Dullah’s book by situating the paintings in the time's turbulent political and social context. Using a range of secondary sources available to the author (the book originated from a Master’s thesis in History at Gadjah Mada University), Abdulbari cogently put together a picture of each artist, their stories and fate after the war, giving recognition to their important contributions and legacies, and a response to Dullah’s ambition for dokoementasi nasional.

Indeed, it was a singular man’s ambition that drove this project of documentation. Thwarted twice to document historical events during the turbulent period, he sent his young students to the front line to complete what he had failed to do. Yet, in both publications, none of the authors seem to think that sending children to the front line would be ethically questionable. The traumatic experiences experienced by these artists seemed to occur with the tacit understanding that war is an act of force and, theoretically, has no limits.

Toha, for example, witnessed how Indonesian fighters hacked a Dutch soldier to death, Sri Suwarno’s fate was unknown after 1949, and Sarjito was captured by the Dutch and sentenced to seven years in a youth prison in Tangerang.6 Instead, praises for their innocence, bravery and patriotism in the acknowledgements by the vice president, mayor and Sultan of Yogyakarta and the sponsor of the 1978 exhibition encapsulated the overall response:

Thousands of lives have been sacrificed, millions of [property] were destroyed and much suffering were experienced by Indonesians to achieve the independence. All events related [to the conflict] have been sweetly documented by the children who were in their teens, driven by patriotism where they volunteered themselves to be war reporters without ulterior motives.7

In Abdulbari’s book:

Their paintings are truly authentic and depict what really happened. Especially in the case of Dullah’s five students, the paintings are truly innocent and naïve but therein lies the honesty [of the paintings].8

In both books, images function as historical agents. They not only record events of the time but also influenced the way in which those events are being viewed, namely as a propaganda, documentation, or eyewitness accounts. With the role of images as agents more pronounced during times of conflict, what kind of agency or imagery do we see in these books? Unsurprisingly, what we get is a masculine view of the war; all the artists are men (or boys), and both books were written and edited by men. This is despite existing records confirming that Indonesian women actively participated as combatants, journalists and members of ancillary groups.9 Yet, within these books, they were invisible, appearing only as “devoted mothers with patience and love.”10 Despite their evidentiary claims, images of war and conflict are complex representations during a violent time. For this reason, while both books provide important sources about the revolutionary time in Indonesia, one must also note their omissions are as significant as their inclusions.

Notes

1. See Mikke Susanto and Irwandi, “Sejarah and Makna Fotografi Karya Pelukis Istana, Dullah (History and Meaning Behind the Photography Work of Dullah, the Palace Painter)," in Jurnal Rekam 16, No.1, 2020: 1–14.

2. Fatih Abdulbari, Melukis di Tengah Perang (Painting in the Middle of War) (Yogyakarta: Dicti Art Lab, 2023), 17.

3. Abdulbari, Melukis di Tengah Perang, 14–15.

4. Abdulbari, Melukis di Tengah Perang, 90.

5. Abdulbari, Melukis di Tengah Perang, 101.

6. Dullah, Karya dalam Peperangan dan Revolusi (Paintings in War and Revolution) (Jakarta: PN Balai Pustaka, Ministry of Education and Culture, 1982), 15.

7. Dullah, Karya dalam Peperangan dan Revolusi, 9.

8. Abdulbari, Melukis di Tengah Perang, 185.

9. See Galuh Ambar Sasi, “The meaning of independence for women in Yogyakarta, 1945‒1946,” in Revolutionary Worlds: Local Perspectives and Dynamics during the Indonesian Independence War 1945‒1949, eds. Bambang Purwanto et al., (Amsterdam University Press, 2023), 35‒46. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.399493.5.

10. Dullah, Karya dalam Peperangan dan Revolusi, 15.