Vietnamese Lacquer Painting: Between Materiality and History

Written to accompany the 2017 exhibition Radiant Material: A Dialogue in Vietnamese Lacquer Painting, this essay discusses conceptual shifts in Vietnamese lacquer painting, as seen in the work of Nguyễn Gia Trí and Phi Phi Oanh, the two artists featured in the exhibition.

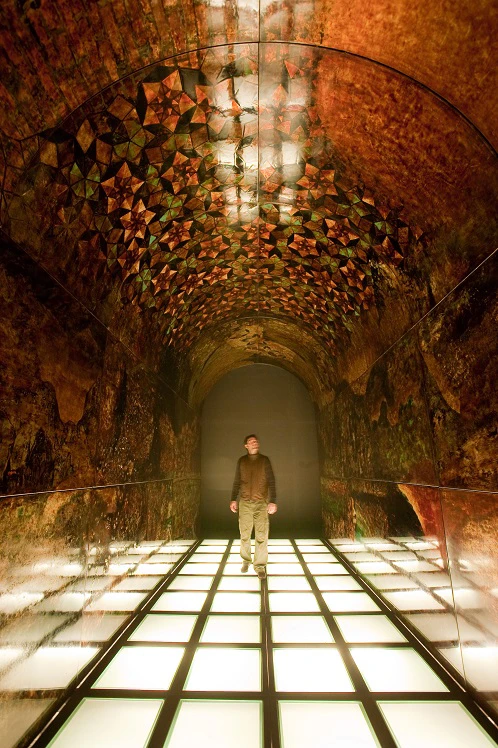

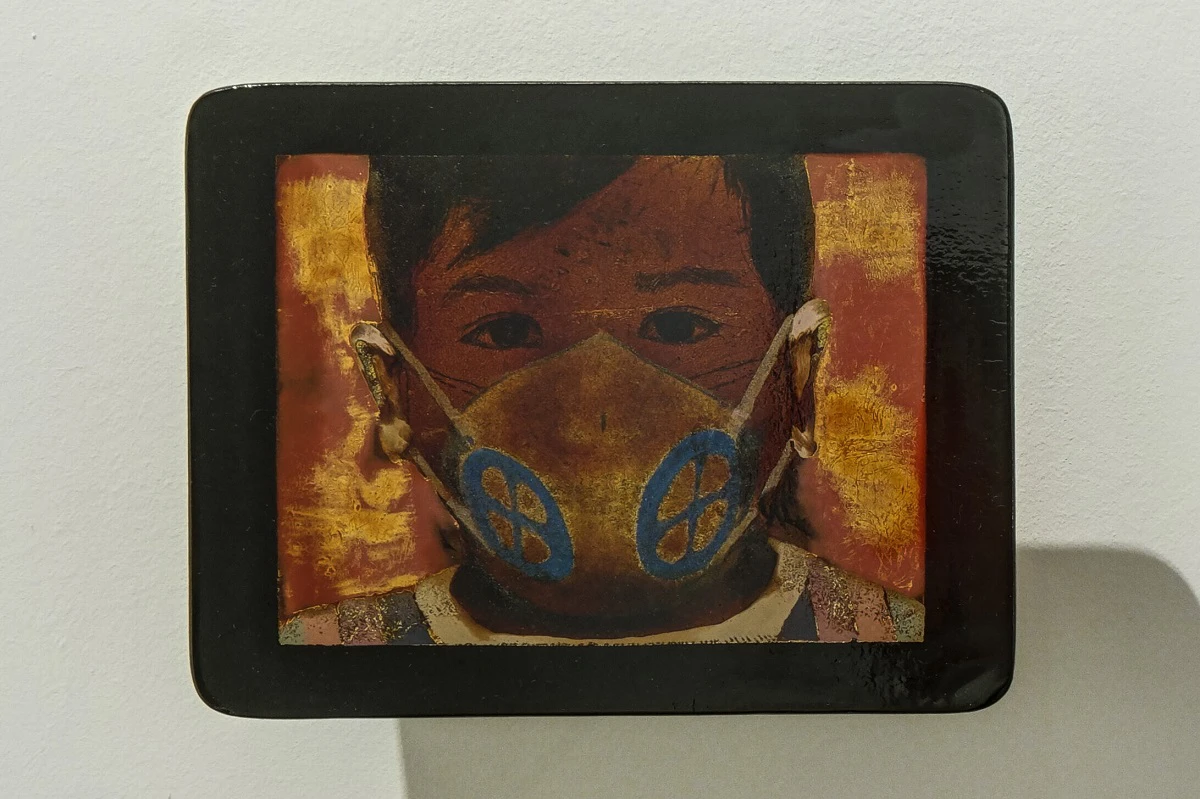

Phi Phi Oanh

In exhibition view of Radiant Material: A Dialogue in Vietnamese Lacquer Painting, National Gallery Singapore, 2017.

Photo by Ken Cheong.

This essay was originally written to accompany the exhibition Radiant Material: A Dialogue in Vietnamese Lacquer Painting, Nguyễn Gia Trí and Phi Phi Oanh, National Gallery Singapore, 2017.

Translucency and opacity, roughness and sheen, surface and depth, radiance: the use of lacquer in Vietnamese art is inextricably linked to the substance’s unusual materiality.1 Natural lacquer, or sơn ta, has been in use for centuries in Vietnam, for both practical and aesthetic reasons. It could give a hard and impermeable surface to everyday objects and structures, while the luminous effect created by layers of red-gold lacquer could elevate an object from the profane to the sacred realm, as seen in temple sculpture. From the 1930s, lacquer became widely used as a painting medium, applied to a flat, two-dimensional surface.2 This offered the painters of the era a potent path to localising the influences of Western painting, creating a new art form that was simultaneously modern and Vietnamese. After 1954, in the postcolonial period, such experiments came to be reframed as national achievements.3 In this way, developments in lacquer painting in the 20th century can be linked to broad historical and ideological paradigm shifts.

However, artists’ fascination for the medium transcended such historical boundaries. Lacquer painting’s history thus must also be seen as an ongoing inquiry into the material properties of the substance itself. As Tô Ngọc Vân, a passionate advocate for lacquer painting, wrote in his manifesto-like text of 1948:

"The radiant substance of lacquer pleases artists who are thirsting to find a new medium, more eye-catching and more moving than oil paint. The substances of “cockroach-wing” lacquer, black lacquer, gold and silver in lacquer are changeable, flexible, no longer substances without soul […] Not one red of oil paint can stand beside the red of lacquer without being made pale. There has never been a black of oil paint that could be put beside the black of lacquer without being made to seem faded and motionless." 4

The exhibition Radiant Material: A Dialogue in Vietnamese Lacquer Painting takes the material qualities of lacquer as its point of departure. It presents two artworks made using sơn ta. The first, Les Fées (The Fairies), was made in the 1930s, in the heyday of lacquer’s modern development by one of Vietnam’s most innovative painters, Nguyễn Gia Trí. With its ambitious scale and variety of visual effects, it is a statement of lacquer’s expressive capacities. Pro Se is a new installation by contemporary artist Phi Phi Oanh, who is Vietnamese-American and based in Hanoi. Her practice over the past decade has reimagined the technical and conceptual boundaries of the lacquer medium. Pro Se was commissioned by National Gallery Singapore as a response to Les Fées, but the connection between the two works is conceptual rather than formal. Both use the organic sơn ta lacquer and share the iterative production process of layering, inlaying, sanding and polishing. But while the monumentality and style of Les Fées was responsive to the needs and values of artists in Hanoi in the 1930s, Pro Se is an inquiry into the relations between the lacquer medium and contemporary visuality. Through a series of different components, Pro Se explores the potential of a medium that is inherently physical, material and tied to climate, in an era when images are increasingly viewed as digitised, disembodied, ephemeral and device-based.

Product for the Colonial Market, or Modern Expression?

The use of lacquer as a painting material began with the innovations of artists working at the École des Beaux Arts de l’Indochine (EBAI) in Hanoi, during the French colonial period. This art school, founded in 1925, promoted aspects of academic art pedagogy under the European model, such as drawing from life and painting in oil. The inaugural director, Victor Tardieu, also encouraged students to localise their work. A lacquer painting studio was introduced in 1927, where the artisan Đinh Văn Thành, from a village specialising in lacquer, worked alongside students like Trần Văn Cẩn and Trần Quang Trân, and their French painting teachers Alix Aymé and Joseph Inguimberty.5 The result of this collaboration was an open and experimental approach to lacquer. The EBAI was also involved in producing artisanal items for sale in the colonial market, and some artists therefore produced decorated lacquer furniture and boxes, as well as lacquer paintings. However, the distinction between art and craft, artists and artisans, was a sensitive issue in this period, embedded in the cultural politics of the colony: the divide between the French “artist” and the Vietnamese “artisan” implied a hierarchy of value and status. Some Vietnamese artists fought for their position as artists, contesting the lesser position that colonial discourse tried to assign them.6 The implications of this discourse spilled over into the reception of the developing field of lacquer painting.7

Trí was widely acknowledged as the artist who moved lacquer painting most definitively away from the realm of decorative arts and craft.8 Les Fées was painted early in his career, and is an immense work realised in ten narrow vertical panels. It is one of his most striking and ambitious paintings. The work is open to multiple interpretations. As Trí worked as an illustrator and satirical cartoonist for the modernising periodicals Phong Hóa (Mores) and Ngày Nay (Nowadays), he was connected to Hanoi’s literary intelligentsia, who were intent on modernising both Vietnamese society and its forms of cultural expression. His experiments in lacquer can thus be seen in parallel with the new developments in Vietnamese literature and poetry at the time.9 Aspects of Les Fées can also be thought to engage with sources from European art (especially Henri Matisse—Nguyễn Gia Trí appears to have referred to Matisse’s 1905‒1906 Joy of Life for the composition of Les Fées). Additionally, Trí’s embrace of the lacquer medium can be read through the lens of his avowed nationalism.10 However, none of these interpretations sufficiently capture the overwhelming impression given by the artwork itself: that it is intended as an experimental essay into the capacities of the lacquer medium.11

The work’s most noticeable characteristic is the juxtaposition of varied techniques and effects. In the lower left, it begins with an expanse of red lacquer that appears thick and matte. Immediately above, the lacquer is applied in multiple translucent layers which have then been sanded back, causing the red lacquer to appear to dissolve and then reappear amongst blacks, browns and fragments of gold. The form of a woman appears loosely as an area of colour, but she is present, largely through an eggshell inlay forming her face and hand. Curving above, the variegated coloured lacquer marking out a tree trunk is contained by a thick gold line, separating it from a section of black lacquer so opaque and shiny that it appears almost viscous. Throughout the composition, a variation in opacity and translucency is matched by a disorienting variation in open and closed forms, positive and negative spaces.12 Trí exaggerated this disorienting quality by using the same technique to describe different types of phenomena: one use of eggshell inlay, for example, describes the subtle fall of light on a face, while elsewhere, it creates a solid volume within an architectural form; gold appears in leaf and powdered form, as thick, expressive lines and thin meticulous ones, and painted into incisions in the surface of the work. By clustering these different effects, the artist draws insistent attention to the medium, emphasised by the untrammelled, almost rough, treatment of parts of the painting. In later works, such as Landscape of Vietnam (1940), in the collection of National Gallery Singapore, Nguyễn Gia Trí combined a similar variety of lacquer techniques within a single perspectival space, creating a sedate and meticulous composition. By contrast, the deliberately free and experimental treatment of the lacquer in Les Fées can be read as a self-conscious assertion of the artist’s unbridled creativity—a message which had a loaded significance in the colonial context in which the work was made.

Lacquer as Substance and Process

To appreciate the full impact of Les Fées, it is necessary to acknowledge how difficult it is to achieve such an expressive effect using a technique that is inherently slow and meticulous, affected by climate, the seasons and has the unpredictable qualities of an organic substance. The French lacquer painter Alix Aymé saw the process as a kind of antidote to industrial modernity, writing that:

"We are often unaware of what tireless perseverance is necessary to conquer this most rebellious of substances. The lacquer artwork is born slowly, coat by coat, worked, polished with love, and only reaches perfection after months or years […] In an era where is seems that the machine must more and more take the place of man, beautiful lacquers attest to the wisdom of those who knew, disinterestedly, how to submit themselves to the exigencies of a severe technique, in order to realise a marvellous collaboration of material and spirit." 13

While her account is tinged with a kind of Orientalism—with lacquer representing a pre-modern “east”—it nonetheless reflects the poetics of a demanding technique.

The substance of Vietnamese sơn ta is derived from the sap of the rhus succedanea tree, one of several related lacquer-producing trees in Asia.14 To harvest the lacquer, the tree is tapped through incisions in the trunk. Quality is affected by the climate, the season, the age of the tree, and even the placement of the incision. The harvested lacquer settles into layers, each with a different grade of purity. The lacquer is then worked, either by hand or with a churn. When worked with a wooden paddle, the lacquer becomes a soft brown colour, known colloquially in Vietnamese as cánh gián, or cockroach wing. If worked by an iron tool instead (or with the addition of iron powder), a chemical reaction causes the lacquer to reach an opaque black, known as sơn then.

To prepare the lacquer baseboard, or vóc, a flat wooden board is wrapped in lacquer-soaked cloth. The surface is smoothed out with a mixture of lacquer, wet clay and sawdust. Then, layer after layer of lacquer is applied. Each layer must be carefully set to hardness, which can only happen at a particular level of humidity. The artist must work in the correct season, or carefully induce higher humidity by hanging wet cloth in a contained space where the lacquer can set. The dried individual coats of lacquer—of which there can be dozens—are individually sanded and polished. This creates the artist’s painting surface. It is usually a deep black, although by adding pigment to the final layers a red ground can also be made.

To paint the lacquer, the artist must conceive of multiple layers, which may not be completely visible in the finished work. This is because the process works by building up layers of different coloured lacquers and inlays, and then sanding them back down. There is an inherent element of chance, as it is not always apparent how under-layers will look as they resurface through the sanding. The first layers to be added to the vóc are the inlays, which can be crushed egg shell, snail shell or mother of pearl, creating a range of whitish, greenish or purplish tones. Fragments of shell are meticulously flattened and crushed into wet lacquer, sometimes laid into a shallow trough cut into the baseboard. Next to be added are the layers of coloured lacquer. Traditionally, the colours were restricted to the translucent brown cánh gián, black, and different tones of red, which were made by mixing natural red pigments into the lacquer. In the past, it was difficult to create cool tones, as the reactive nature of the lacquer responded poorly to many pigments.15 Today, chemical pigments can be mixed with the sơn ta to allow for a more extensive range of colours. The artist may also add metals, either beneath or on top of the layers of lacquer paint. These are typically silver, gold or aluminium in powder form, which can be sprinkled onto wet lacquer, or else applied in leaf form.

Once the painting stage is complete, the artist may sand the lacquer down. This sanding process was one of the characteristic techniques of the colonial period, and sơn mài (or sanded lacquer) became a by-word for Vietnamese lacquer painting. Through sanding, hidden under-layers of colour and metal or shell inlay can reappear, and it is this interplay between the layers which gives lacquer paintings their compositional complexity. The radiance of a lacquer painting is also caused by the intimation of depth, created by light passing through the build-up of translucent lacquer coats, until it meets the opaque vóc beneath. After the first sanding, the artist may continue the process of painting lacquer and sanding back. When the artist is satisfied with the composition, the work is given a final polish—at this stage, using fine polishing powders or even the artist’s hands alone—and is complete.

The Vóc in the Expanded Field

For the lacquer painters of the 1930s, the vóc, or baseboard, represented a work surface that resembled the white rectangle of the oil painter’s canvas: blank, flat and two-dimensional. Like the canvas, the vóc could sustain the “window” metaphor so crucial to the history of Western painting, where a two-dimensional surface could create the illusion of a three-dimensional world. This was critical for lacquer’s transition in status from craft to art at the time.

But for the contemporary artist working in lacquer, what is the relevance of such a starting point? In her work of the past decade, Phi Phi Oanh has consistently challenged the sense of the vóc as a two-dimensional surface. In Specula, of 2007–2009, she experimented with binding sơn ta to epoxy-fibreglass composite, creating an immersive lacquer work supported by a large-scale structure in the form of a curved apse. The vóc was thus pushed into an expanded form, and lacquer was returned to its traditional alliance with architectural space. In Palimpsest, of 2013–2015, lacquer was bound to transparent sheets of glass, which were then projected like slides. Seen through projected light, the lacquer was bright and delicate, its manifold layers visible rather than concealed. Liberating the medium from a dark and opaque substrate, this work represented the de-materialisation of the vóc, while the glass slide and projector format alluded to modern visual technologies like microscopy, photography and cinema.

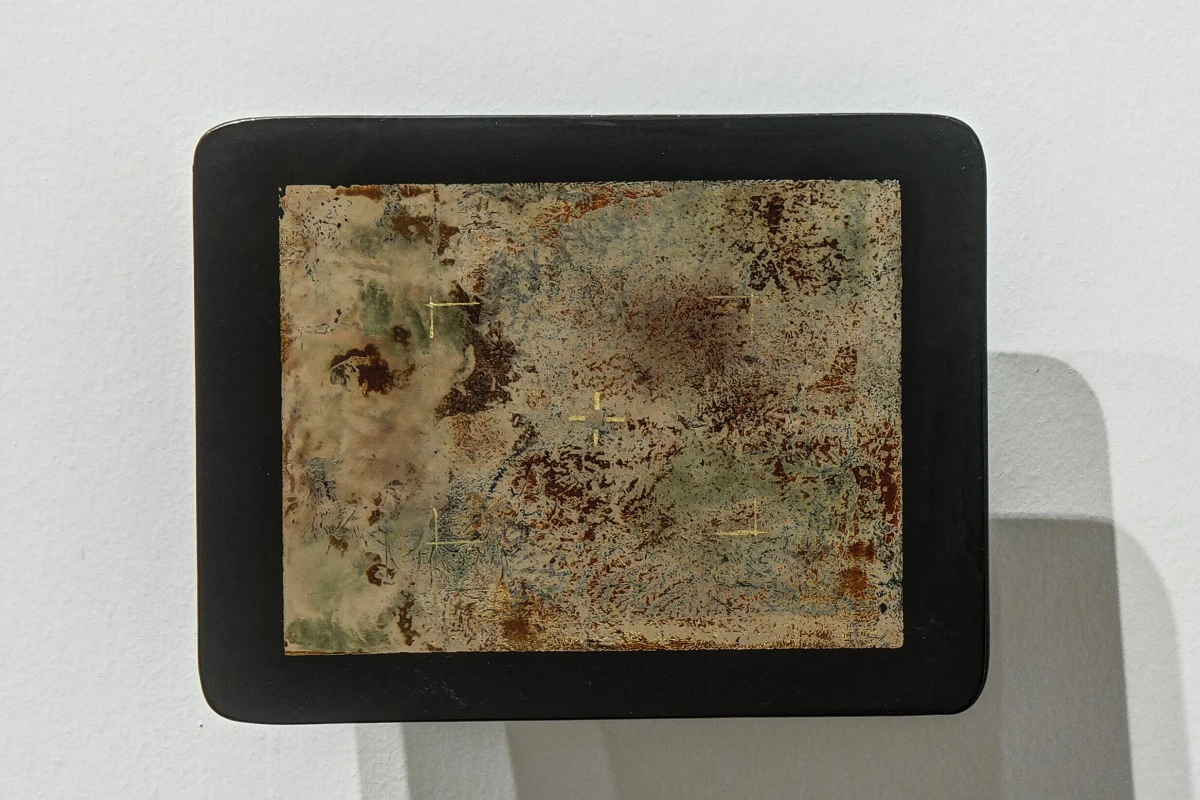

Pro Se continues the artist’s investigation of the relationship between lacquer and visuality, pushing into a meditation on contemporary experiences of image-making and viewing. Recurring throughout the installation are small format works on 24 x 18.5cm panels, evoking iPad-like tablets. Constructed in either lacquer on wood or lacquer on metal, the deep, polished black of the lacquer simulates the sleekness and sheen of a digital device. The format is a loaded double entendre, referring both to the ubiquitous digital screen, but also the traditional screen format of much East Asian lacquer painting. We might also consider the retina, our internal screen onto which all that the eye takes in is projected, and which, due to the portability and ease of digital photography, is now closer than ever to the streams of images preserved in our personal devices. A series of 40 small format paintings within Pro Se refers explicitly to a digital photo stream. They recall a flood of consciousness that sweeps up images from the precious to the banal, the accidental to the narcissistic, as well as the “digital abstractions” produced by pixelation, blurring, dead and sleeping screens, and the after-images of retinal fatigue. When rendered in lacquer, images which, in digital form, are taken or discarded within seconds, attain an uncanny prominence and dignity, forcing us to give them new, considered attention.

Installation Views

The installation also addresses the exaggerated powers of sight rendered by new technologies of digital viewing and image delivery. A sequence of lacquers on metal tablets contains a poetic evocation of a geographical search function like Google Maps, with the series depicting a zooming out from the exhibition space to the universe. Although this visual experience has become increasingly democratised and normalised, as such functions are easily accessible on personal devices, the treatment in lacquer contrives to return a sense of intimacy and wonder to this astronomical reach. Viewers are invited to handle these tablets, with the cool weight of the metal reminding us that our digital devices have their own compelling tactile qualities. According to the artist, the weight of the tablet also makes us conscious of physically being in a location in space, during an otherwise disembodied experience of viewing digital images. Elsewhere in the installation, lacquer paintings on glass tablets are presented under a magnifying device, exploring the visuality of the extreme close-ups and internal imagery. Under the magnifying lens, the lacquer material appears separated and distended, its layers probed and revealed. It is a play between medium and image, as the painted motifs blur the line between digital and physical anatomies. Throughout these elements of the installation, lies an insistent substantive presence of the lacquer itself, which returns the dematerialised and disembodied image to material presence and physicality.

Conclusion

For Phi Phi Oanh, whose practice is iterative and intuitive, it is the experience of a long immersion in the studio and a sustained inquiry into the material that generates the conceptual apparatus of her art. Looking at the evident concerns of Les Fées, perhaps the same could be said of Nguyễn Gia Trí. For both artists, the lacquer medium and its qualities are the driving force behind timely conceptual and aesthetic developments. The work of both artists can be read through such expansive interpretive thematics as modernity, nationalism, identity or contemporary visuality, but in each case, these potential meanings are manifested as an experimental and reflexive approach to the medium.16 By reinvesting the history of Vietnamese lacquer painting with a close reading of its materiality, it is possible to move beyond ideological abstractions, and appreciate the singularity of a discourse generated through the particular qualities of a compelling medium.

Notes

- Parts of this essay relating to the history of Vietnamese lacquer painting and the work of Nguyễn Gia Trí have been adapted from Phoebe Scott, “Forming and Reforming the Artist: Modernity, Agency and the Discourse of Art in North Vietnam, 1925–1954,” (PhD. Diss., University of Sydney, 2012). I would also like to thank Phi Phi Oanh, whose ideas and insights about lacquer painting––both in relation to this project, and in our conversations over the years––have been formative and influential for me.

- There is one existing example of a late 19th century pictorial lacquer painting on a flat substrate in the collection of Vietnam Fine Arts Museum in Hanoi. However, it was not until the 20th century that such a practice became widespread.

- On the nationalist reception of colonial period developments in art, see Nora Annesley Taylor, Painters in Hanoi: An Ethnography of Vietnamese Art (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), 38–40.

- Tô Ngọc Vân, “Sơn mài (Lacquer),” Văn Nghệ 5 (1948): 21, trans. Phoebe Scott with the assistance of Vân Trần.

- On the technical and artistic developments made in this studio, see Quang Việt, Hội họa sơn mài Việt Nam (Vietnamese Lacquer Painting) (Hanoi: Fine Arts Publishing House, 2005), 170–171 and Kerry Nguyen-Long, “Lacquer Artists of Vietnam,” Arts of Asia 32:1 (2002).

- Taylor, op. cit., 33–34. A petition signed by students protesting their status as artisans was published in a Vietnamese newspaper, see Nguyễn Đỗ Cung, “Những sự cải cách của Trường Mỹ Thuật Đong Dương (Reforms of the Indochina School of Fine Arts)”, Ngày Nay 144 (1939): 9.

- For example, an interesting discussion of this debate is Tô Ngọc Vân, “Sơn ta: mỹ thuật thuần túy hay mỹ thuật trang sức?” (Lacquer: A Pure Art or a Decorative Art?), Thanh Nghị 45 (1943): 2-4.

- This is reflected in some reviews of Trí’s work from the period, which emphasise his role as a creative artist such as Tô Ngọc Vân (writing as Tô Tử), “Nguyễn Gia Trí và sơn ta” (Nguyễn Gia Trí and Lacquer), Ngày Nay 146 (1939): 9.

- I have written previously about Nguyễn Gia Trí’s connections to the literary circle of Hanoi, as well as of the various possible interpretations of Les Fées. For more details on these interpretations, see Phoebe Scott, op. cit., 114‒126 and Phoebe Scott, “Towards an Unstable Centre,” in Reframing Modernism: Painting from Southeast Asia, Europe and Beyond, exh. cat., (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore: 2012), 26‒27 and 36‒37. The work is also discussed in the context of the Asianising tendencies at the EBAI in Phoebe Scott, “Imagining ‘Asian’ Aesthetics in Colonial Hanoi: The École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine (1925-1945)”, in ed. Fuyubi Nakamura, Morgan Perkins and Olivier Krischer, Asia through Art and Anthropolgy: Cultural Translations Across Borders (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 53 – 54.

- Scott, “Forming and Reforming the Artist”, 114–126.

- That Nguyễn Gia Trí’s practice was largely driven by the encounter with the medium is also borne out by several statements about his process that he made later in life, as recorded by his informal student, lacquer artist Nguyễn Xuân Việt. See Nguyễn Xuân Việt, Họa sĩ Nguyễn Gia Trí nói về sáng tạo (Painter Nguyễn Gia Trí’s Words on Creation) (Ho Chi Minh City: Nhà xuất bản Văn Nghệ, 2009).

- It should be noted that originally the work also had visible figures in its central area, which now only appear minimally, due to the darkening that can occur with lacquer over time, depending on how it is combined with other materials. This is evident from comparison with an earlier image of the artwork, published in Alix Aymé, “La Laque en Indochine et L’École des Beaux-Arts d’Hanoi” (Lacquer in Indochina and the School of Fine Arts in Hanoi), Études d’Outre Mer (December 1952): 409 – 412, images n.p.

- Alix Aymé, “L’Art de la Laque” (The Art of Lacquer), Tropiques: revue des troupes coloniales 327 (1950): 53, 60.

- In preparing this account of the lacquer working process, I am indebted to several existing published accounts, including those of Quang, op. cit., Nguyen Long, op. cit., Aymé, “L’Art de la Laque”, as well as the kind assistance of a number of lacquer artists, including Nguyễn Văn Bảng of the Trường Trung cấp nghề Tổng hợp Hà Nội (Hanoi Vocational School), Phi Phi Oanh and Nguyễn Xuân Việt.

- Pigments that could form yellows and greens were already known by the 1940s, see Aymé, “L’Art de la Laque”, 58, but these did not come into wide use in Vietnam until after 1954.

- In a recent article, Pamela N. Corey notes that certain contemporary artists of the Southeast Asian diaspora (especially Sopheap Pich and Dinh Q. Le) use a critical engagement with craft materials to forge a conceptual practice. Although Corey relates this phenomenon primarily to diasporic subjectivity, it is also possible to see this as a general case for forms of local conceptualism forged through engagement with specific culturally loaded materialities, see Pamela N. Corey, “Beyond Yet Toward Representation: Diasporic Artists and Craft as Conceptualism in Contemporary Southeast Asia,” The Journal of Modern Craft 9:2 (2016), 161–181.