The Nanyang School: A Fantasy in the Hearts of Commentators

In this essay, Yeo Mang Thong questions the overarching frameworks of the “Malayan school” and “Nanyang school” that have been used as broad descriptors of art produced in Singapore during the 1950s and 1960s.

Dancing Lesson

1952

Mixed media on paper, 45.6 x 61 cm

Gift of the artist's family

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

© Family of Chen Chong Swee

In this essay, Yeo Mang Thong engages with the historical development and usage of the term “Nanyang” and its accompanying qualifiers in relation to art in Singapore. Tracing the entanglement of these terms alongside shifting visions of national and regional identity from the 1950s to the 1960s in Singapore, Yeo questions overarching frameworks of the “Malayan school” and “Nanyang school” that have been used as broad descriptors of art produced in this time period. His observations and analyses draw from English and Chinese newspaper sources, as well as interviews, to present a critical perspective in the ongoing discourse about the aesthetic and stylistic characteristics of art from Singapore. This English translation accompanies Yeo’s original Chinese essay, included below, to promote accessibility of his research as well as discourse.

Yeo Mang Thong is a Singaporean scholar and senior educator whose research is recognised in the area of pre-war Singapore art and artists. He is known for his use of newspaper sources from the pre-war period as a means to study Singapore’s art history, and his 1992 publication Xinjiapo zhanqian huaren meishushi lunji (Essays on the History of Pre-War Chinese Painting in Singapore) is one of the most cited references for scholars in the field. Other publications include the 2019 title《新加坡美术史论集》(Essays on the History of Chinese Painting in Singapore) and the 2017 title《流动迁移 · 在地经历-新加坡视觉艺术现象(1886-1945)》, which the National Gallery Singapore translated and published as Migration, Transmission, Localisation: Visual Art in Singapore (1886-1945) in 2019. Yeo holds a Master of Arts in Chinese Studies from the National University of Singapore, and was awarded a National Day Commendation medal in 1996.

The Nanyang School: A Fantasy in the Hearts of Commentators Yeo Mang Thong

Translated from Chinese by Chow Teck Seng

Preface

“Nanyang,” literally “the southern oceans,” historically referred to the geographical region south of the Chinese mainland. Between 1927 and 1948, many of China’s intellectuals migrated south to Malaya (today Malaysia and Singapore), and they soon came to narrow Nanyang’s scope by equating it to Malaya. For instance, traditional Chinese calligrapher Goh Teck Sian, who was one such migrant, said in 1955 that the “Nanyang style [of art]” was equivalent to the “Malayan style.” The terms “Singapore and Malaya,” “Malaya” and “Nanyang” were used interchangeably then, and was not till 1961 that Hsu Yun Tsiao made it clear that in the Chinese world, “Nanyang” referred to Southeast Asia1.

Beginning from the 1920s and up till the 1950s, ethnic Chinese organisations, schools, literary and art circles and business corporations of Malaya often used “Nanyang” as a prefix. One such example is “Nanyang literature,” a term created to refer to Malayan Chinese literature.

“Nanyang” was also used to demarcate visual art that fuses Eastern and Western painting techniques in the depiction of local scenery, people and cultures, as in “Nanyang style” and "Nanyang feng."2 The Westerners living in Malaya, however, preferred “Malayan style.” As such, we now have three different terms referring to the same visual art form: Malayan style, Nanyang style, and Nanyang feng.

The Chinese community favoured the use of “Nanyang” to express their attachment to the rich multicultural flavours of this area3, while Westerners preferred “Malayan” as it related to “The Grand Design,” a colonial policy aimed at creating a coherent entity of the region.

Within art circles, “Nanyang style” and “Nanyang feng” are often used interchangeably, which is inaccurate. The two are not equivalent. “Feng” (风) is a much richer concept than “style” (fengge风格) in Chinese cultural traditions, and the use of “Nanyang style” precedes that of “Nanyang feng.” Some translators also erroneously use the term “school” for “Nanyang style”—“style” refers to the characteristics of a piece of art, whereas “school” is a collective concept. Even seasoned practitioners in the field mix the terms up, leaving readers confused.4

Part 1: How the confusion began

In March 1950, the Singapore Art Society (SAS) held its first annual exhibition of works by local artists at the British Council Hall. Roy Morrell, a member of the exhibition’s selection committee and professor at the University of Malaya, said that “the Singapore Art Society is trying to establish a ‘Singapore school’ of painting5 […] in common with other parts of the world, there has been a general revival of amateur art in Singapore since the war […] A few members of Singapore Society of Chinese Artists were breaking away from tradition and experimenting on an essentially Malayan line.”6 We will come back to the connotations of “Malayan line”, but for now, let us see how Morrell’s words affected people’s perceptions towards art in these parts.

1.1 In an article for The Straits Times, the special correspondent deemed the exhibition “first-rate and not unencouraging”.7 The article analysed the works of Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng, and Chen Chong Swee:

“Chen Wen Hsi’s Coffee Boys… [is] not quite western, not quite eastern in conception.”

“Cheong Soo Pieng, a rather surer hand, [had] the same qualities in his watercolours, notably Cathedral and Scenery. These are most attractive pictures.”

“Chen Chong Swee particularly illustrates the point again in two of his scrolls, Morning Toilet and A Home on the Beach, but this synthesis of style is at least hinted at in many compositions.”

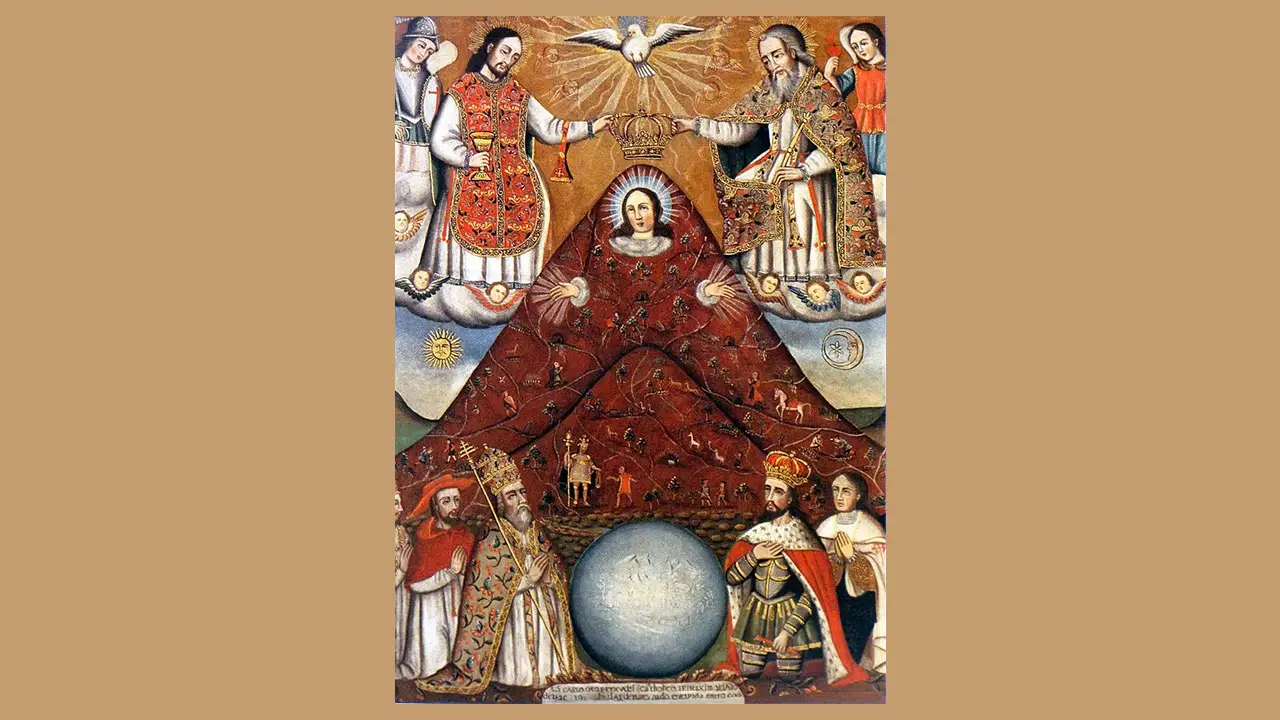

Chen’s A Home on the Beach featured a stilt house, sampan boats, and Malay women and children, evoking a spirit that was distinctly Nanyang, as did his earlier paintings. His Kampong Scene (1937), for instance, was filled with Nanyang imagery: a lone boat lying gently on shore with stilt houses standing silently in the background; passing clouds and moving water; and a sense of time passing slowly, just as people’s lives did.

1.2 In their reports on the exhibition, Nanyang Siang Pau and Sinchew Jit Poh described Cheong Soo Pieng’s oil paintings and watercolours as “displaying bold and innovative techniques,” concluding that “his artistic spirit is a rare gem in the field.” They also commented on Liu Kang’s oil paintings, describing them as “rich in colour” and “true to life.”

In November 1951, Chen Chong Swee, Liu Kang, Chen Wen Hsi, and Cheong Soo Pieng held a group exhibition. Sinchew Jit Poh reported on it, commenting that by “fusing the characteristics of Chen Chong Swee’s and Liu Kang’s art, we get something that represents the style of a new Malaya.”8

These commentaries focus on techniques and subject matter, which tells us that the Malayan style was characterised by fusing Eastern and Western painting techniques and often depicted local scenery and humanity.

1.3 In October 1950, SAS held an exhibition of works by Singapore teachers and art students, with the hope of displaying a Malayan style of painting. Viewers found the use of traditional Chinese ink painting techniques to depict of local scenery visually refreshing. As The Straits Times put it: “A bunch of red rambutans hanging amid green leafage on a Chinese scroll painting forms a novel and pleasant touch of Malayan influence upon Chinese life.”9

It must be said, however, that despite media outlets creating the impression that such art was fresh and novel, migrant artists had been incorporating the flavours of Nanyang and rich colourful tropical scenery into their works since the 1930s. Those earlier efforts were described as “exotic” and “a fusion of Eastern and Western art.”10 This is an important point that I will get back to later.

Works by art students from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) at the same exhibition attracted the attention of The Straits Times reporter Noni Wright. He interviewed NAFA’s principal, Lim Hak Tai, for his report, which opened with a quote from Lim: “I can teach a student to paint in Eastern styles, I can teach him in Western styles. He learns all ways, and then it’s up to him to experiment and develop his own style. In Malaya the styles can mix. It will take time for a ‘Malayan school’ of painting to develop. You can’t force it, but it will come.”11

In a 1951 NAFA publication, which included Wright’s report, Lim emphasised once again that NAFA aimed to “communicate Eastern and Western art and establish a new art of Malaya”. How, then, did this “new art of Malaya” morph into “a ‘Malayan school’ of painting”? Was something lost in translation? Or were there other forces at work?

1.4 In a 1952 article,12 Morrell expounded on the emergence of a Malayan culture in the arts:

“If as it is often claimed, ‘East meets West’ in Singapore and Malaya, it might well be asked whether anything expressing a truly ‘Malayan’ culture has arisen in any of the arts […] We forget that culture is something which should give meaning to life here and now, and that if there is to be a true Malaya—not merely an assortment of unfused and conflicting elements, with nothing but a geography in common—that culture should express something for all of us […] What is happening in the other arts I do not know, but it seems to me that in painting there is the beginning of a truly Malayan style.”

In the same article, he cites artworks by Chen Wen Hsi, Chen Chong Swee, and Cheong Soo Pieng as examples of what the “Malayan style” looked like: an attempt to fuse Eastern and Western drawing techniques, and which feature local scenery and humanity as subjects. The following quotes by Morrell elaborate on the significance of “the Malayan line,” which appeared in the review of the 1950 SAS exhibition mentioned earlier:

“Chinese shop boys [is] a study by Chen Wen Hsi, an artist of international repute. It shows Chinese delicacy of line with western realism in composition.”

“[Chen Chong Swee] has been led away from the refinement and idealism of Chinese art towards the humour and realism of everyday life, and his paintings are ‘composed’ in the Western sense, instead of existing more or less in vacuo on their scrolls.”

“[The] strength of Soo Pieng’s painting, at first sight so western, and with rather a cubist synthesis, derives as much from the flexible brush stroke line of Chinese calligraphy.”

Morrell viewed the unique Malayan style—an artistic concept—in the context of politics, whereby art comes under the umbrella of an imagined cultural entity. His vision of such a “Malayan style” eventually became the “Malayan school.”

The art exhibitions by SAS mentioned above created a ripple effect, with a slew of related terms popping up in reports put forth by the English media: “an essentially Malayan line,” “Singapore school,” “Singapore style,” “Malayan style,” and “Malayan school.” All of them were by Westerners residing in these parts, which brings us to the following conclusion: the Grand Design of the British, conceived in 1945, was designed to merge the various British colonies scattered across Southeast Asia into one coherent entity for easy rule.13 Aside from political consolidation, elements such as cultural soft power were also important considerations.

In August 1947, the British Council was set up in Singapore. During a press conference on 25 August the same year, representative J.P. Lucas stated that “exhibitions of paintings, photographs, etchings and musical items would be arranged by the Council. He hoped [sic] the local people to come forward and help him.”14

This is a good time to remind readers that migrant artists were already experimenting with a local style of art some two decades before terms like “Malayan style” came into vogue with the media. Lucas’s statement is one example that shows how the British Council had clear political motives, and was considering different ways to best mollify those under colonial rule—in this case, using the arts.

Cultural soft power was to be used to help foster closer ties with Malaya. In addition, close cooperation with the SAS (whose seven founding members were, with the exception of Liu Kang and Inche Mahat bin Chadang, all Westerners residing in Singapore)15 would promote a common Malayan identity among the country’s various ethnicities, hence mitigating the rising threats from communism and nationalism.16

Morrell and Wright were staunch supporters of the Grand Design.

Part 2: The myth of the Malayan school

Did this “Malayan school” talked about by the Westerners ever exist? We will attempt to answer this question by examining Lim Hak Tai’s art ideology, as well as Chinese media reports on the local art scene in pre-independence Singapore.

2.1 Did Lim Hak Tai ever talk about a “Malayan school”?

Lim Hak Tai set up NAFA in 1938 because Singapore—a part of Nanyang—was a key traffic hub connecting the East and West, and was decidedly multicultural. He had hoped that the school would eventually give rise to art with the tropical characteristics distinct of the Nanyang. Come 1951, Lim reiterated that NAFA aimed to “communicate Eastern and Western art and establish a new art of Malaya”—in other words, it aimed to establish a Nanyang painting style that embodied both East and West and was innovative at the same time. Lim was someone who walked the talk, writing academic essays and creating paintings that described and demonstrated his vision for art in Nanyang. A decade’s worth of hard work culminated in NAFA’s annual exhibition of 1948, which attracted some 8000 visitors and positive reviews on how everything was, indeed, uniquely Nanyang.17

In 1954, Lim proposed that “artists should understand trends in World Art, depict subject matter that displays social awareness, and create new art with ‘Nanyang feng.”18 A year later, Goh Teck Sian interpreted “Nanyang feng” as something that was “in fact, Malayan feng.” In Goh’s view, Malaya was on the path to independence and hence could not be without her own national feng. This feng was tropical, resulting from a melting pot of traditional art forms of the local Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Eurasian communities.19

The 1950s was a time of widespread anti-vice and anti-colonialism protests. Lim felt that art should reflect life—and in fact, artists were actively creating works that reflected the demands of the people. Lim felt that the “new art of Malaya” should be imbued with elements expressing the historical significance of the times, and also effect change in society. This was what he meant by the term “Nanyang feng”—it was a concept based on the desire for a cohesive and inclusive multicultural society.20

At the same time, migrant Chinese were slowly identifying themselves as people of Nanyang. That local identity was something born of organic interaction. It was certainly not the imagined identity the British had in mind with their Grand Design, and neither was it something transplanted wholesale China. Everyone was first and foremost Malayan. This is clear in the six guiding principles Lim mapped out for Nanyang Art, the first of which was “to fuse the cultures and customs of the various ethnicities.”21

Lim himself was an accomplished artist who created multiple works reflecting his ideals for a what having “Nanyang feng” entailed. For instance, Malay Wedding (1954) was a display of multiculturalism; Sentosa (1953) an exotic tropical scene; Inner Beauty (1954) a response to the anti-vice movements; and Riot (1955), a piece on anti-colonialism influenced by Cubism. NAFA students, too, did not disappoint. At a 1956 exhibition, Lim praised their works for blending societal themes of the day with art.22 Such works included Chua Mia Tee’s Epic Poem of Malaya, Tay Kok Wee’s Picking, Lee Boon Wang’s Construction Workers, and Lim Yew Kuan’s Searching for Truth. By 1958, NAFA graduates were active in the art scene, setting up organizations as the Equator Art Society. Lim felt that his vision was finally a reality. 23

For two decades since NAFA was established in 1938, Lim had been calling for art with tropical characteristics distinct of Nanyang, and for a new art of Malaya that reflected Nanyang feng and was in the Nanyang style. Nowhere, however, do we see any traces of a "Malayan school.“

2.2 Did the Chinese media in pre-independence Singapore ever talk about a “Malayan school”?

The short answer is no. According to my research, official and private entities in pre-independence Singapore only emphasised “the effort to create a Malayan Art,” and never a “Malayan School.” Below are some examples that illustrate what was actually said then.

2.2.1 1956: Chen Wen Hsi’s solo exhibition. Ho Kok Hoe, then president of the SAS, said that Chen was “a famous Malayan artist who […] was committed to creating art with a unique local style”. Vice-president Dr Michael Sullivan also praised Chen’s art as a bridge that could link the East and West, and that it combined the best of both worlds, be it in terms of technique or culture.24

2.2.2 1957: Cheong Soo Pieng’s solo exhibition in Penang. Critics praised his work as “containing the unique style of Nanyang."25

2.2.3 1957: NAFA’s 15th anniversary exhibition. Visitors described the works as “rich in colour” and possessing “the unique sentiments of Nanyang art.”26

2.2.4 1958: SAS’s 9th annual exhibition. Then-president Ho Kok Hoe said in his speech, “What the exhibits present are a type of ‘Malayan style.’ They are neither Western nor Eastern art.”

2.2.5 1958: In a commentary published for NAFA’s anniversary exhibition, Marco Hsu wrote that from “the local subject matter, the strong colours, you knew at a glance if you were looking at something from Malaya […] however, it may be too early to define what constitutes 'Malayan style.'"27 If it was too early then to talk about a “Malayan style” then, surely a “Nanyang school” would have been out of the question.

2.2.6 4 Feb 1960: The Equator Art Society invited then Minister for Culture, S. Rajaratnam, to speak at their second annual exhibition. The minister said that the exhibition was further proof that “we have competent and dedicated local artists who are striving to create a Malayan art.”28

2.2.7 2 Jun 1960: A countrywide art exhibition was held to commemorate the first anniversary of Singapore attaining self-governance. Lee Khoon Choy, then Minister of State for Culture, pointed out that “The inaugural Singapore Art Exhibition is clear proof that local artists are working hard to creating Malayan art. However, the characteristics of a Malayan Style will only come about with time.”29

2.2.8 1963: NAFA’s 25th anniversary art exhibition. Then acting principal Lim Yew Kuan said that NAFA was confident in achieving its goal of establishing a new art based on a “Malayan style.”30

2.2.9 1966: SAS’s 17th Local Artists’ Exhibition. Lim Yew Kuan, by then principal of NAFA, spoke as the vice-president of SAS: “All the exhibits here display the unique individuality, creativity, and vitality of each artist. This is a correct and healthy direction to pursue, so that we may create an art form unique to us.”31

In this section, I have collated various snippets written about Singapore’s art scene, specifically about solo and national art exhibitions in the decade of 1956 to 1966. While terms like “new art” and “style” were commonly used, I could not find a single instance of "Malayan school."

In that case, do we have a “Nanyang school”?

Part 3: Does a “Nanyang school” exist?

Between 1981 and 1985, Singapore’s Ministry of Culture and the National Museum of Singapore held a series of retrospectives as a tribute to Liu Kang, Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Chong Swee and Georgette Chen. On 5 November 1985, Nanyang Siang Pau carried an article on Georgette Chen’s retrospective, praising the five artists for grooming many successors for local art and, more importantly, establishing a Nanyang painting style and forming an influential “Nanyang school”.32 The keywords to note here are “establish […] a Nanyang school”. The article suggests that a Nanyang school blossomed under the influence of these five pioneer artists.

Back when Chen Chong Swee, Cheong Soo Pieng, Liu Kang and Chen Wen His held their sensational exhibition Pictures of Bali, it too was seen as a milestone for the rise of a Nanyang school. Some critics felt that Chen Chong Swee was undoubtedly a key member of a Nanyang school.33 On the other hand, there were others who felt that Liu Kang’s life was more closely linked with the development of a Nanyang school.34

Now, for something to be termed as a school of art, it should possess four characteristics. One, members should share the same views on art and possess similar painting styles distinct from that of other schools. They should also have a comprehensive theoretical framework for their views on art. Two, the artists should be active in the same geographic region, and are representatives for their style of art. Three, works in this style have been passed down to the present and still exist. Four, there is a continuation beyond the original group of artists. Does the "Nanyang school" possess these characteristics?

3.1 The pioneer artists painted in vastly different styles

Liu Kang wrote that Cheong Soo Pieng’s style was ever-changing—from Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism to Abstraction, Cheong had tried them all before reverting to realism and imbuing his oil paintings with the characteristics of Indonesian painting. His was a unique style. Chen Wen Hsi, on the other hand, was well versed in both Chinese and Western painting. His oil paintings were influenced by artists like George Braque and Paul Klee, and were exceptional in idea, composition, colour, and execution. Chen’s style reminds one of a grand master. Chen Chong Swee focused on ink and oil painting, achieving much in both realms. His works boasted tight compositions and a dark palette. As for Liu Kang himself, he professed to loving Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, and all things cheerful and bold.35 From this, we can see that the four artists possessed vastly different painting styles.

To further clarify my doubts, I interviewed several NAFA lecturers, including Chua Mia Tee, Wee Beng Chong, Poon Lian and Tan Kee Sek. All of them shared that view that the four aforementioned artists had such distinctly different styles that it was doubtful a Nanyang school ever existed.

Artist Koh Mun Hong also shared some of these doubts. “After all,” he said, “Indonesia has many exceptional artists and could be considered number one when it comes to Southeast Asian art. If the first-generation artists, simply by virtue of having painted local subject matter, could be considered a Nanyang school, wouldn’t that be too shallow a view?” Koh felt that it would be more appropriate to name the four artists Exceptional First-generation Artists of Singapore instead.

Art critic Toh Lam Huat felt that the so-called Nanyang style or Nanyang school is, up till this day, only in an embryonic stage. The definitions mostly centre on geography or imagery of depicted subject matter, and have in no way taken shape.

Ex-NAFA president Choo Thiam Siew gave his take based on the concept of an art school: “It is true that the four artists held an exhibition following their trip to Bali, which attracted great attention and interest from the art world. However, to say that that was a Nanyang school is not appropriate.”

President of the Federation of Art Societies Singapore, Stephen Leong, also felt that it was still too early to conclude whether, in those decades, a Nanyang style—let alone a Nanyang school—was formed.36

3.2 The “Nanyang school” lacks a comprehensive theoretical framework

Liu Kang left many essays. Unfortunately, they are of topics too diverse to be of any use in establishing a theory of art. This might have been a result of—in Liu Kang’s own words—“being too busy with painting to be concerned with establishing a theory.”37 Chen Chong Swee’s writings too, while possessing gems related to the principles of drawing and establishing a painting practice38, were lacking a comprehensive framework.

3.3 It begs the question to derive a “Nanyang school” from the Pictures of Bali exhibition

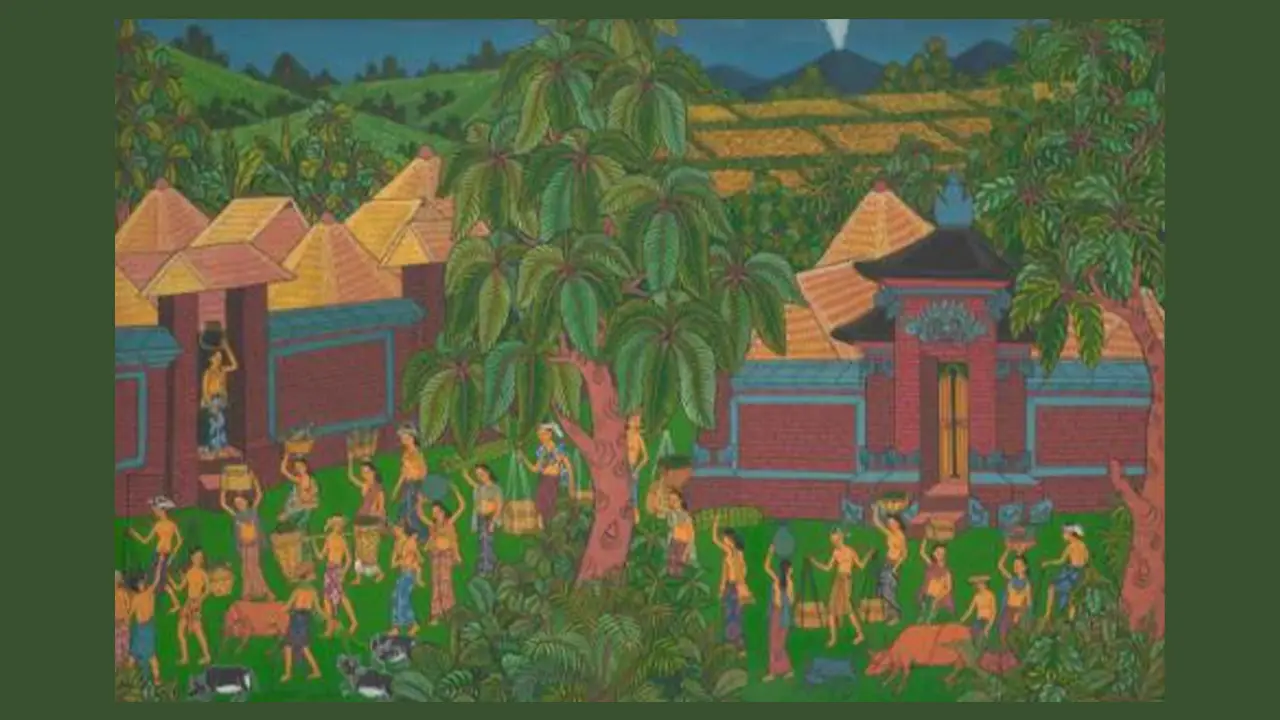

The Pictures of Bali exhibition ran from 6 to 15 November 1953 at the British Council Hall. The exhibits featured oil, pastel, and ink brush paintings, amounting to some 100 pieces. The Indonesian Consul commended the exhibition for giving visitors the opportunity to learn about the humanity and scenery of Bali.39 Visitors were mainly Westerners, taking up some 60% of the total number. Buyers were also mostly Westerners, with the High Commissioner, Malcolm MacDonald, visiting three times and buying a total of six artworks. He even invited the four artists to his official residence for tea.40 Generally, visitors found the exhibits innovative in style, special in subject matter, and novel to Singapore.41 SAS President, Gibson-Hill, praised the artists for expressing the humanity and scenery of Bali in various styles.42

The four artists have contributed greatly to Singapore’s art history; Pictures of Bali was brimming with the flavours of Nanyang. However, that hardly amounts to a Nanyang school. Let us recall that in 1958, Lim Hak Tai called for “new art reflecting Nanyang feng”—a Nanyang style of the times, for the times. With that in mind, even if we were to take a step away from “Nanyang feng,” to say that Pictures of Bali alone established a Nanyang style and hence a Nanyang school is a logical leap.

In 1979, a retrospective was held in Kuala Lumpur to recognise NAFA’s contributions to regional art. This retrospective is viewed as the first attempt to define Nanyang art and Nanyang style. Redza Piyadasa praised NAFA for cultivating a group of Nanyang artists, which includes NAFA alumni, teachers, enrolled students, as well as students who took private lessons from NAFA teachers. T.K Sabapathy felt that Nanyang artists depict their subjects by fusing traditional Chinese painting techniques with techniques from the School of Paris, resulting in the Nanyang style.

Sabapathy was also a key proponent of tying the Nanyang style to Pictures of Bali. He felt that “it was as though they were following Lim Hak Tai’s call”—to paint Nanyang in a way that reflects actual life—when they went to Bali to paint. Referencing Lim was meant to make his article appear more credible. Indeed, people became convinced that the styles of the four exhibiting artists directly resulted from their Bali trip; as a result,they even equated Nanyang artists with the Nanyang style.43 However, one only needs to read Liu Kang’s article on the trip, published in Nanyang Siang Pau, to know that Liu had always wanted to go to Bali, Lim Hak Tai or not; he didn’t even mention Lim.

Piyadasa and Sabapathy may be art historians, but they were not fully informed of the key ideas of Nanyang art or its development before making the above statements. This is due to a lack of access to Chinese sources from pre-independence Singapore. As a result, they distorted what Nanyang style connotes and has diluted Lim’s “Nanyang feng.”

In the 1980s, “Nanyang feng” somehow became merely “Nanyang style,” which commentators then morphed into the “Nanyang school.” This piling of errors upon errors even made it as far as Japan. In 2002, the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum held an exhibition titled Nanyang 1950-65: Passage to Singaporean Art, which was based on the views of Piyadasa and Sabapathy. Organisers translated “Nanyang feng” as “Nanyang style” and listed the four artists as representatives. What’s worse was that they defined “Nanyang art” as works which depict exotic flavours and women, even going so far as to group social realist pieces in a separate category as a point of contrast.44 They clearly did not understand that the idea of reflecting societal realities was, precisely, part of Lim Hak Tai’s conception.

Of course, the four artists are key figures in Singapore’s art history; I have no intention of diminishing their contributions. But the fact remains that their wonderful paintings of Nanyang do not amount to a Nanyang school. The “Nanyang school” and “Malayan school” seem to be fantasies that exist solely in the hearts of commentators.

3.4 Nanyang feng is no more

Following independence and economic stability in the late 1960s, artworks that reflect ideologies and have the aim of educating the masses slowly fell out of favour. The Equator Art Society held its last annual exhibition in 1968. With that, Nanyang feng slowly fizzled and faded away.45 How then do we talk about continuation beyond the pioneering artists?

In 2003, the Society of Chinese Artists (SOCA) organised an exhibition with the theme of “Nanyang feng.” A collection of the artworks was also published. Poon Lian, then SOCA president, wondered if Nanyang feng, with its combination of modernist ideologies and social realism, had died off due to a lack of nourishment. He went on to question exactly what Nanyang feng was and if it had truly become a thing of the past. “Do we want ‘ASEAN art’ or ‘Singapore feng’? Have we completed the homework Mr Lim Hak Tai set for us, the later generations? What is the way forward? May this exhibition inspire more like-minded people to create a new Nanyang feng.” Poon’s laments, doubts, and hopes for the future capture the uncomfortable status of Nanyang feng.

Conclusion

In 1950, Westerners residing in Singapore put forth the idea of a Malayan style. In 1954, Lim Hak Tai, in response to the times, called for new art with Nanyang feng. While both of these had the aim of creating a coherent cultural identity for the people in these parts, the former was a reaction to the wishes of the colonial government and the latter was a people’s hope for independence.

In the two decades following NAFA’s establishment, all the way up till Singapore’s independence, the art world used terms like “Malayan style,” “unique style of Nanyang,” “Nanyang feng,” “new art in the Nanyang style,” “Nanyang art,” and “Malayan art” to describe art that used both Eastern and Western techniques to depict local people and scenery. In the 1960s, S. Rajaratnaman and Lee Khoon Choy, then Minster for Culture and Minister of State for Culture respectively, shared the opinion that a Malayan artistic style would take a long time to develop and form. How, then, do we even begin to talk about a Nanyang school?

The 1980s saw the erroneous premise that the four artists went on their trip to Bali “as if to answer Lim Hak Tai’s call.” This spiralled into the illogical conclusion that the Bali trip established the Nanyang style, which then became a Nanyang school. This all but took over art commentaries written in English. I hope I have made clear that this mix-up was due to mistranslations, misunderstandings, and misinformation.

Singapore began a new chapter in 1965. I fear it would not be appropriate for today’s artists to persist in using the term “Nanyang feng” to describe Singapore art. After all, “Nanyang feng” was borne out of a specific time and is now merely a part of history.

To end, I would like to bring to your attention Chen Chong Swee’s small wish for Singapore art: “May the Singapore art world one day create an internationally renowned ‘Singapore School.’” This may have been said in the 1970s, but its value is timeless. It does and should continue to inspire us.

Notes

- In 1955, D.G.E. Hall’s A History of Southeast Asia became the first published text to treat Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines as one coherent region. (T/N: nations have been listed using their present names.) Quoted in Li Jinsheng 李金生, “一个南洋,各自界说:“南洋”概念的历史演变” (Yige Nanyang, gezi jieshuo: ‘Nanyang’ gainian de lishi yanbian) [One Nanyang, various definitions: The historical development of “Nanyang” as a concept], Asian Culture, no. 30 (2006): 120–121.

- T/N: The terms brought up by the author, 风格 (fengge) and风 (feng), are usually loosely translated as “style.” This is not entirely accurate. Fengge generally refers to a set of characteristics that define, in this context, a type of art. Feng, which literally translates into “wind,” is a broader concept that encompasses traditions, fashions and customs. As concepts, “style” does not fully map onto fengge. However, I chose “style” to represent “fengge” to reference the way in which artists choose to portray their subject matter.

- In the 1920s, the Malayan Chinese literary circle proposed in various literary supplements that literature should have Nanyang feng [or display Nanyang colours; 南洋的色彩 (Nanyang de secai)]. In 1950, Marco Hsu’s essay “南洋之美” (Nanyang zhi mei) [The beauty of Nanyang], found in a collection of writings with the same title, also praised the various aspects of Nanyang.

- Yao Tianyou 姚天佑 (ed.), 南洋风作品集 (Nanyang feng zuopinji) [Nanyangism] (Singapore: The Society of Chinese Artists, 2003), 6–7 and 12–14.

- This is also a view expressed by then SAS Chairman Gibson-Hill: “And the hope is, Dr. C. A. Gibson-Hill, chairman of the Society, told me yesterday morning, that eventually a distinct Singapore style will emerge, a marriage between the Eastern and Western styles of painting.” See Mary Heathcott, “Colony Artists: Singapore Re-Visited,” The Straits Times, 24 November 1950.

- “Aim at ‘S’pore School’ in Art,” The Straits Times, 17 March 1950.

- “S’pore Art Show A Big Success,” The Straits Times, 13 March 1950.

- Gao Yun 高云, “四人画展观后记” (Siren huazhan guanhouji) [Thoughts from viewing the Pictures of Bali exhibition], Sinchew Jit Poh, 25 November 1951.

- “The Rambutans,” The Straits Times, 24 October 1950.

- Yiming 一鸣, “华人美术研究会第四届展览参观记” (Huaren meishu yanjiuhui disijie zhanlan canguanji) [Thoughts from viewing the fourth exhibition of the Society of Chinese Artists], Sinchew Jit Poh, 12 December 1939.

- Noni Wright, “East and West Meet in a Malayan Style of Painting,” The Straits Times, 29 October 1950.

- R.C.R. Morrell, “Towards a Malayan School of Painting,” The Straits Times Annual for 1952, 38–40.

- Ou Qingch i欧清池 and Li Yiping 李一平, eds., 新加坡华人思想史 (Xinjiapo huaren sixiangshi) [The history of thought of Singapore Chinese], (Singapore:新加坡斯雅舍, 2018), 134.

- “Chief Aims of British Council in Singapore,” Malaya Tribune, 26 August 1947.

- “S’pore Art Society,” The Straits Times, 23 November 1949.

- On The Great Design and SAS, see Seng Yu Jin, “Art and ideology: The Singapore Art Society and the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960),” in From words to pictures: Art during the Emergency (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2007), 10–15.

- “南洋美专展览会开幕:琳琅满目独具南洋风趣” (Nanyang meizhuan zhanlanhui kaimu: linlangmanmu duju Nanyang fengqu) [NAFA Exhibition opens: dazzling array uniquely Nanyang], Nanyang Siang Pau, 21 February 1948.

- Lim Hak Tai 林学大, “刊首语” (Kanshou yu) [Foreword], Nanyang Siang Pau, 9 April 1954 and “南洋美专十六周年纪念举行大规模全校美展” (Nanyang meizhuan shiliu zhounian jinian juxing daguimo quanxiao meizhan) [Large scale schoolwide exhibition held to commemorate NAFA’s 16th anniversary], Nanyang Siang Pau, 10 April 1954.

- Goh Teck Sian 吴得先, “南洋风” [Nanyang feng], in《南洋青年美术》(Nanyang qingnian meishu) [Art of the Nanyang youth] (Singapore: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, 1955).

- Yeo Mang Thong 姚梦桐, “南洋风的界说” (Nanyang feng de jieshuo) [The definition of Nanyang feng],《源》(Yuan), no. 114 (2019).

- Lim Hak Tai 林学大, “刊首语” (Kanshou yu), in《南洋青年美术》(Nanyang qingnian meishu) [Art of the Nanyang youth] (Singapore: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, 1955).

- Yeo Mang Thong 姚梦桐, “狮岛的历史印记——一九五十年代的艺研会与巡回美展” (Shidao de lishi yin ji: yijiuwushi niandai de yiyanhui yu xunhui meizhan) [Historical marks of Singapore: SAS and art exhibitions in the 1950s],《怡和世纪》(Yihe shiji), no. 40 (July 2019), 106–110.

- “林学大述创校理想已次第实现” (Lin Xueda shu chuangxiao lixiang yi cidi shixian) [Lin Hak Tai talks about how his vision when establishing NAFA has been realised], Nanyang Siang Pau, 25 July 1958.

- “陈文希画展开幕” (Chen Wenxi huazhan kaimu) [Chen Wen Hsi art exhibition opens], Sinchew Jit Poh, 5 May 1956 and “陈文希中西画展昨由最高专员苏高德揭幕” (Chen Wenxi zhongxihuazhan zuo you zuigaozhuanyuan Sugaode jiemu) [Chen Wen Hsi art exhibition opened yesterday by High Commissioner], Nanyang Siang Pau, 5 May 1956.

- Nanyang Siang Pau, 1 July 1957.

- “南洋美专假纪念堂举行常年美展今开幕” (Nanyang meizhuan jia jiniantang juxing changnian meizhan jin kaimu) [NAFA’s annual art exhibition opens today at Victoria Memorial Hall], Nanyang Siang Pau, 29 November 1957.

- Marco Hsu玛戈, “南洋美专常年美展观感” (Nanyang meizhuan changnian meizhan guangan) [Thoughts on NAFA’s 1958 art exhibition], Sinchew Jit Poh, 5 November 1958.

- “Minister: Artists have a duty to society,” The Straits Times, 5 February 1960.

- “全星美术展览会今日下午在纪念堂揭幕” (Quanxing meishu zhanlanhui jinri xiawu zai jiniantang jiemu) [Art exhibition opened this afternoon at Victoria Memorial Hall], Nanyang Siang Pau, 2 June 1960.

- Ji Qing 纪青, “! 让美术摇篮的花朵盛开罢!” (Rang meishu yaolan de huaduo shengkai ba) [May the flowers of the cradle of art blossom!], Nanyang Siang Pau, 20 July 1963.

- “本地画家作品展览昨日举行开幕典礼” (Bendi huajia zuopin zhanlan zuori juxing kaimu dianli) [Local artists’ exhibition opened yesterday], Nanyang Siang Pau, 23 April 1966.

- “Georgette Chen’s Retrospective”, Nanyang Siang Pau, 5 November 1985, 5. This article states that Georgette Chen is the last artist to be honoured in the series, which would conclude in the same year.

- Ho Kah Leong, “画与画理兼优的画家——陈宗瑞” (Hua yu huali jianyou de huajia: Chen Zongrui) [Proficient in art practice and theory: artist Chen Chong Swee] (Singapore: Chen Qixin, 2020).

- Yeo Wei Wei, Liu Kang: Colourful Modernist, (Singapore: National Art Gallery, 2011), 8.

- Liu Kang, “四十五年来新加坡的西洋画” (Sishiwunian lai Xinjiapo de xiyanghua) [Singapore’s Western paintings in the past 45 years], in《刘抗:文集新编 》(Liu Kang: Wenji xinbian ) [Liu Kang: Essays on Art and Culture], ed. Sara Siew萧佩仪, (Singapore: National Art Gallery, 2011), 232–233.

- Huang Xiangjing 黄向京, “梁振康画展延续南洋风貌” (Liang Zhenkang huazhan yanxu Nanyang fengmao) [Stephen Leong’s art exhibition carries on the flavours of Nanyang], Lianhe Zaobao, 8 January 2019.

- “廿年来新加坡之艺术动态” (Niannian lai Xinjiapo zhi yishu dongtai) [Art in Singapore in the past 20 years], Nanyang Siang Pau, 1 July 1955.

- “When painting the scenery of the South, I always use Chinese techniques. In this particular painting, however, I complemented Chinese techniques with Western techniques for showing light and shadow. This might be a first attempt, but I don’t like how it turned out. I shall not paint like this again.” See Grace Tng 唐瑞霞, “生机出笔端——陈宗瑞的艺术 Strokes of Life: The Art of Chen Chong Swee,” in Strokes of Life: The Art of Chen Chong Swee, eds. Low Sze Wee and Cai Heng (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore), 36–43.

- “刘抗、陈文希、陈宗瑞、钟泗宾峇厘画展昨日开幕” (Liu Kang, Chen Wenxi, Chen Zongrui, Zhong Sibin Bali huazhan zuori kaimu ) [The Pictures of Bali exhibition opened yesterday], Nanyang Siang Pau, 7 November 7 1953.

- “四画家峇厘绘画展览会参观者西人最多” (Si huajia Bali huihua zhanlan canguanzhe xiren zuiduo ) [Visitors to Pictures of Bali mainly Westerners], Nanyang Siang Pau, 15 November 1953.

- “本坡四画家峇厘画展参观者众,麦唐纳氏订购数幅” (Benpo sihuajia Bali huazhan canguanzhe zhong, Maitangna shi dinggou shufu) [Pictures in Bali draws crowds, MacDonald buys several pieces], Nanyang Siang Pau, 8 November 1953.

- Nanyang Siang Pau, 7,8 and 15 November 1953 and The Straits Times, 16 November 1953.

- Yeo Mang Thong 姚梦桐 and Foo Kwee Horng 胡贵宏, “多元对话的反思——解读陈宗瑞的战前作品以及‘南洋美术’的界说 Reflections on diverse dialogue: Interpreting Chen Chong Swee’s pre-WWII works and the definition of ‘Nanyang art,” in Strokes of Life: The Art of Chen Chong Swee (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), 57–72.

- Lü Caizhi 吕采芷, “林学大的艺术世界” (Lin Xueda de yishu shijie) [Lim Hak Tai’s world of art], in Crossing Visions: Singapore and Xiamen: Lim Hak Tai and Lim Yew Kuan Art Exhibition (Singapore: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, 2011), 51.

- Yeo Mang Thong 姚梦桐, “他们走过的峥嵘岁月——掀起赤道艺术研究会的重重面纱” (Tamen zouguo de zhengrong suiyue: xianqi Chidao yishu yanjiuhui de chongchong mian sha) [The extraordinary times they experienced: lifting the veils on the Equator Art Society],《怡和世纪》(Yihe shiji), no. 41 (October 2019) and no. 42 (January 2020).

- Chen Chong Swee 陈宗瑞, “艺苑拾零” (Yiyuan shiling) [Tibits from the realm of art and literature], in Unfettered Ink: The writings of Chen Chong Swee, Low Sze Wee and Grace Tng, eds. (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), 55.

“南洋画派”——纯然是论者流淌心中的美丽憧憬

姚梦桐

前言

“南洋”泛指中国南方的海洋,是以中国为中心而言的地理区域名称,范围无严格限定。1927至1948年间大批中国知识分子南来,他们的到来出现了以新马两地即是“南洋”的概念,“南洋”的词义缩小了。第一代书法家吴得先于1955年解释“南洋风”即是”马来亚风”,如此“南洋”的词义,等同于“新马”也等同“马来亚”,在那个年代里,“新马”、“马来亚”、“南洋”这三个词经常替换使用,1961年许云樵明确提出“南洋”专指东南亚,至此南洋有了公认的定义。1

在上世纪20年代与50年代华人团体、学校、文艺界、商业机构习惯以南洋为前缀,如文艺界视新马华文学为“南洋文艺”。一种呈现“融汇东西方画技,题材以当地人文景致”的视觉艺术也以 “南洋”为前缀,如“南洋风格” (Nanyang style) 以及添加了新元素的 “南洋风” (Nanyang feng)。旅居本地的西方人则以 Malayan style” (马来亚风格) 名之。 同一区域(新马)同一艺术风貌的绘画作品出现不同指称:“马来亚风格”、“南洋风格”以及“南洋风”。华人本着对南洋绚烂多彩的在地情愫而以“南洋”作前缀,2 西方人则在英国人“宏伟计划”(Grand Design)的框架中,从融和多元文化的政治视角考量而以“马来亚”为前缀。

艺术界往往把“南洋风格”与“南洋风”混为一谈。这两个概念的出现有先后序列,“南洋风格”比“南洋风”早,“南洋风格”不等同于“南洋风”;后者的“风”并非风格,有其深厚的中华文化意涵,比“南洋风格”更为丰富。译成英文时,“南洋风格”等同“南洋风”,甚至把“南洋风格”译成“南洋画派”;风格是绘画作品所呈现的状态,画派属于群体概念。这几个概念模糊不清,即便是资深美术工作者诠释“南洋风格”与“南洋风”时也让读者满头雾水,不知所云!3

1. 一块石头泛起层层涟漪

1950年3月新加坡艺术协会(Singapore Art Society)首届本地画家作品展在文化协会礼堂举行。画展遴选委员之一马来亚大学教授慕礼尔(Roy Morrell) 在一次演讲会上指出:“与世界其他地区一样,战后新加坡艺术活动普遍复兴。新加坡艺术协会正试图团结艺术家创立‘新加坡画派’ 4……。有几位新加坡华人美术研究会的成员尝试打破传统创造一种本质上以马来亚画风为主的路线。”5 文中“马来亚画风为主的路线”的内涵,后文将给予解释。慕礼尔这一番话犹如一块石头抛进水里泛起层层涟漪:

1. 《海峡时报》特稿《新加坡艺术展大获成功》赞誉“新加坡艺术协会1950首届本地画展“是一个一流且令人鼓舞的展览。” 6文中分析陈文希,钟泗滨以及陈宗瑞的作品:

"陈文希《咖啡男孩》的艺术构思“不太西方也不太东方”

“钟泗滨具有同样特点,他的水彩与油画一样优秀,水彩画《大教堂》和《风景》尤其引人注目 “

“陈宗瑞两幅画轴《清晨的洗手间》与《海边人家》,尤其表现这种特点,这种构思再次显示了他已往的绘画风格。”7

展品 《海边人家》,画幅右边树丛下有浮脚屋,舢舨,马来妇女与小孩,这幅作品沿袭探索画家之前充满南洋情调的作品,如陈宗瑞画于1937年的《甘榜景色》,画面尽是南洋风情,画境丰盈——孤舟静摆,浮脚楼默然静对;白云自白,流水自流,云自无心水自流的“山静日长”东方哲理境界。

2. 《南洋商报》与《星洲日报》的画展报道:“钟泗滨的油画与水彩大胆突破的创新手法,形成的艺术气魄是艺坛的一朵奇葩。刘抗油画色调鲜明浓烈,题材富有生活的现实性”,其参展作品之一《爪哇街》题材来自本地街景。

1951年11月陈宗瑞,刘抗,陈文希以及钟泗滨举行“四人画展”,《星洲日报》记者高云参观展览后报道:“……把陈宗瑞与刘抗的特点融汇陶铸另立典型,从而创造一种代表 ‘新马来亚的风格’。”8

上述几家报章的评论从技巧题材切入,可知“马来亚风格”的特色是“融汇东西方画技,题材多以本土人文景致”为主的画风。

3. 1950年10月艺术协会举办首屆全马教师学生美术作品展,呈现出“一种马来亚风格的绘画”。观众觉得以中国水墨画技法来画本地景物,予人一种崭新的视觉效果:“画轴里一簇簇红毛丹垂挂在绿叶丛中,给观众一种新的、愉悦的视觉享受,这是马来亚景物对华人画家的影响。”9 其实20世纪30年代,南来画家已经将洋溢南洋风情与热带斑驳色彩的景物入画,并以“热带情调”、“融冶中西艺术于一炉”来描述华人美术研究会年展中的艺术现象。10 美专学生的展品引起《海峡时报》记者诺尼·赖特(Noni Wright)的注意。他访问了林学大校长并发表了《东西方艺术在马来亚风格的绘画中相遇》。11 文中引述林校长的一段话语:“我可以教学生画东方风格的画,也可以教他们画西方的风格。学生在创作实践中发展成自己的绘画风格。在马来亚,东西风格可以融汇一起。‘马来亚画派’的发展需要时间,你不能强求,但是它一定会到来” 。这篇文章转载在1951年《南洋美术专科学校画刊》第一集里,该刊《卷首语》林学大重申“沟通东西艺术,建立马来亚的新美术”是美专创办的目的之一。怎么他主张的“马来亚的新美术”在诺尼·赖特的文中却变成了“马来亚画派” ?是语译的偏差或者其他原因?

4. 慕礼尔在1952年《走向马来亚画派的绘画》阐释马来亚文化的艺术形式出现了:

“如果像人们常说的那样,在新加坡和马来亚,‘东方与西方相遇’,那么有人很可能会问,在哪个艺术领域里出现了表达真正‘马来亚文化’的形式。我担心的是我们之中有许多人,尤其是那些非马来裔的马来亚人,把‘文化’ 看作是对往事的怀旧,或是几百英里之外已经难以接近的东西”。“我们忘记了文化应该赋予当下生活以意义,我们也忘了,若要一个真正的马来亚,那么其文化应该代表我们所有人进行表达,而不是只呈现一个由多种元素组成,但除了共同的地理背景之外,内部无法融合、互相冲突的杂烩。[...] 我不知道其他艺术的发生情况,但依我看来,在绘画中已经萌芽了一种真正的‘马来亚风格’” 。12

慕礼尔认为文化赋予当下生活的意义,住在同区域(新加坡与马来亚)的人们应该将周遭的人文景致呈现出来,不应眷恋属于自身的文化,而忽略了一种真正代表马来亚文化之“马来亚风格”已经悄然萌芽。

慕礼尔以大篇幅的文字用陈文希,陈宗瑞与钟泗滨的作品来描述“马来亚风格”——尝试融汇东西方画技,题材多以本土风景人文所形成的艺术风貌。此段文字为慕礼尔“马来亚画风为主的路线”的意义作进一步的申述:

"艺术家陈文希《华人店里的小伙计》,此幅构图结合了中国线条的细腻与西方的写实手法。"

"陈宗瑞脱离了中国艺术的精致和理想主义,转而面对日常生活的幽默和现实主义;他的画作也可视为西方意义上的构造,而不是卷轴上所呈现的那种用线条虚拟构成的画面。"

"钟泗滨画作的实力,乍看是西方却有点立体派,而这衍生自中国书法的线条。"

按照慕礼尔的文章思路:将描述新马区域的独特艺术风貌 “马来亚风格” 披上政治色彩的外衣说成“马来亚文化”——一种共同想象的文化体。他憧憬“马来亚风格”的路线延续下去最终形成“马来亚画派”。

新加坡艺术协会1950年3月与10月的美展泛起“涟漪效应”,新加坡英文媒体对马来亚艺术的描述与展望,众说纷纭:“马来亚画风为主的路线” 、“新加坡画派”( Singapore school)、“新加坡风格”(Singapore style)、“马来亚风格” (Malayan style) 、“马来亚画派” (Malayan school)。提出这几个概念者都是旅居本地的西方人,人们不禁感到吊诡,其中“马来亚画派”的提出更是早在1950,这串疑问可从以下得到答案:

1945英国人的“宏伟计划”(Grand Design)拟把分散在东南亚各英国殖民地以合并方式形成一体化的统治。13当然政治合并之外,也必须设计其他诸如文化软实力的配套。

1947年8月新加坡英国文化协会(British Council)成立,主其事者是卢卡斯(J. P. Lucas)。是年8月25日他在记者会上重申:英国文化协会将为个人或艺术团体安排绘画、摄影等展览并寄望本地人能与他联系。”14 英国文化协会的成立显然有着政治意图以及怀柔政策的考量,希望借助文化软实力拉近与新马的关系,并通过与新加坡艺术协会(创会成员共7人,除刘抗与 Inche Mahat bin Chadang 之外都是旅居本地的西方人。15 首届美展在英国文化协会大厅举行,由代总督麦克伦 Sir Patrick McKerron开幕) 的紧密合作,提倡一种以马来亚文化作为各族共同文化的身份认同,从而缓和共产主义与民族主义高涨的威胁。16 慕礼尔与诺尼·赖特是贯彻这种思维的代言人。

2.“马来亚画派”的迷思

西方人所提的“马来亚画派”出现过吗?下文将从“南洋艺术之父”林学大的美术观,新加坡独立前华文媒体有关画坛活动的资料切入,慎重地审视这问题:

(1)林学大提过“马来亚画派”吗?

1938年林学大创办美专的动机是考虑到位于南洋地区的新加坡是东西交通要道,移民的多元文化,期望建设具“热带特质”的南洋艺术风貌。1951年林学大再次重申“沟通东西艺术,建立马来亚的新美术”(是东西兼容、勇于创新的南洋绘画风格)是美专创办的目之一。林学大与时并进以自身的美术修养与敏锐洞察力,用专业语言的论述与创作实践去描述、去示范他对南洋美术的期许。经过十年辛勤耕耘,美专1948年展的参观人数近8000人,社会的观感是琳琅满目独具“南洋风趣”。171954年林学大提出‘南洋风’ 的新美术。他说:“画家应该了解世界艺术动态的思潮,构思具社会意识的题材,创造出‘南洋风’ (Nanyang feng)的新美术。” 18 吴得先于1955年作出诠释:“南洋风,实即马来亚风。马来亚已走上独立自主的大道,不能不有它的国风。这“风”是以热带情调为主,融汇华巫英印四大民族美术遗留的风格于一炉,沉浸涵咏才可以完成南洋风的美术”。19 “南洋风”中的 “风”即是“国风”。按《诗经》的《国风》是西周时期十五个不同地域的诸侯国,各国有自家风土民情的诗篇。对新马画家来说,马来亚已走上独立自主的道路,美术作品也应具自家独特的艺术风貌。林学大一向主张艺术反映生活,五十年代在反黄色文化,反殖民主义的声浪中,文化工作者提倡爱国文化,以不同艺术形式反映人民诉求,为创造马来亚文化事业作出贡献。林学大期望美术界在发展爱国主义文化的工作中也扮演积极作用,于是在“马来亚新美术”的基础上,注入具时代意义(反黄,与反殖民)的新元素,从而提出“南洋风”的新美术。20 “南洋风”是特定区域、特定时代的产物,它与“南洋风格”的不同是充分体现绘画作品的时代性、配合社会思潮兼具社会功能。

1955 年林学大在《南洋青年美术》的《刊首语》中对南洋美术的内容与形式定出六大纲领:(一)融汇各族文化风尚(二)沟通东西艺术(三)发挥二十世纪科学精神,社会思潮(四)表现当地热带情调 (五)反映本邦人民大众需求(六)配合教育意义,社会功能。21 他南来后经过多年观察思索与艺术实践提出完整的南洋美术概念!“融汇各族文化风尚”位居六大纲要之首,因为它是塑造马来亚文化(爱国文化)的重要组成部分,唯有融汇各族文化才能建立一个多元性、包容性的社会!这是海外华侨自觉性的诉求,与西方人在英国人“宏伟计划”的框架中,以建设马来亚文化作为各族共同文化身份认同的想象体的内涵截然不同。1956年以美专学生为骨干的艺研会巡回美展,画展特刊封面上三个人头,其含义即是华巫印三大民族的团结,折射出华侨逐渐倾向认同居留地的愿望。这与南洋美专初期的成立宗旨:移殖“祖国文化”、“辅助华侨教育”的理念有着天壤之别。1959年冯伟英《为马来亚艺术辛苦耕耘南洋美专校长林学大访问记》,林学大再次重申上述论调,念兹在兹的就是“南洋风”!22

到了50年代末从“马来亚的新美术“发展到“南洋风格新美术”(“南洋风”)日趋定型。1958年林学大以极兴奋的语气强调地说:“我认为沟通中西艺术,形成“南洋风格新美术”的创校理想已次第实现。”23 究竟他的底气从何而来,首先是多年来的创作实践。

1954年林学大《巫族婚礼》反映不同民族习俗,表现社会的多元性,正合乎“融汇各族文化风尚”的理念。1953年洋溢“热带情调”的《圣淘沙》,1954年反黄作品《可怕的时间》,1955年反殖作品《福利巴士罢工》/《工潮》,创作手法受到立体派的影响。颜色是黑、白和灰色,画面的以灰暗为基调,构图新颖,达到震撼的艺术效果。其次从美专学生的作品而来,如蔡名智《马来亚史诗》、郑国伟《劫余》/《拾遗》、李文苑《建筑工人》/《印度工友》、林友权的《余恨》与《寻真理》等都在1956年艺研会举办的“美术巡回展览会”上交出靓丽的成绩。林学大赞赏该次展出的反黄和爱国主义作品,能把现世纪的科学社会思潮和艺术打成了一片。”24 1958年7月留学英国法国的陈存义与赖凤美陆续毕业学成归来。1958年赤道艺术研究第一届画展成功举行并引起社会广泛注意,该会主要领导人都是毕业于美专。林学大艰辛办学,终有回甘,坦言自己创校理想已次第实现!

从1938年创校到1958年,二十年来林学大提出具“热带特质”的南洋风貌、“马来亚的新美术”、 “南洋风”的 新美术、“南洋风格的新美术”,找不到任何“马来亚画派”的蛛丝马迹!

(2)我国独立前华文媒体提过“马来亚画派”吗?

让我用历史来说话,由始至终官方或民间在我国独立之前艺术界一致“强调正努力创造一种马来亚艺术”,压根从未提过“马来亚画派”:

1. 1956年“陈文希中西画展”,艺术协会何国豪会长致辞说:“他是马来亚有数的名画家,在这里生活七年之久……致力于创造一种当地独特风格的作品。” 副会长莎里文(Dr. Michael Sullivan) 推许陈文希的画沟通东西的桥梁,糅合中西画之所长,把欧亚文化融汇贯通。25

2. 1957年钟泗滨在梹城举行画展,论者赞誉他的作品“具有 ‘南洋独特之风格’及美感。” 26

3. 1957年南洋美专第15届学生常年展,给予社会的观感是“色彩强烈,‘南洋艺术’ 的独特情调。”27

4. 1958年艺术协会第九届年展,会长何国豪致辞说:“展品所表现的仍是一种 ‘马来亚的风格’,不属于‘西方或东方的艺术’ ”。

5. 1958年玛戈《南洋美专常年美展观感》,文中“……当地题材,强烈色彩,几乎一看而知为马来亚的产物……关于‘马来亚风格’是怎样的,也许言之过早。”28 按玛戈看法,要谈“马来亚风格”为时尚早,那就遑论“南洋画派”。

6. 1960年2月4日,赤道艺术研究艺敦请文化部长拉惹勒南为第二届美展主持开幕,他在致辞中欣慰地说: “这次展览会进一步证明我们有能力和奉献精神的本地艺术家,正努力创造一种‘马来亚艺术’”。 1960年2月4日,赤道艺术研究艺敦请文化部长拉惹勒南为第二届美展主持开幕,他在致辞中欣慰地说: “这次展览会进一步证明我们有能力和奉献精神的本地艺术家,正努力创造一种‘马来亚艺术’”。29

7. 1960年6月2日为庆祝自治邦周年纪念,举行全星美术展览会,文化部次长李炯才在美展特刊中指出:“第一届全星美术展清楚证明了当地的画家,正在努力创造马来亚的艺术,不过,“马来亚风格’的特性,却有待长期的发展才能形成”。30

1960年文化部长拉惹勒南以及文化部次长李炯才都认为‘马来亚风格’的特性必须经长期发展才能形成。

8. 1963年南洋美专廿五週年美展记者访问林又权代校长,他说:“我们对建立‘马来亚风格’的新艺术的这个目标,怀着无比的信心,这个目标必能达到。”31

新加坡独立以来第一次(1966年)汇集本地画家的作品展——艺术协会第17届个本地画家展,该会副会长林友权致辞时说:“这次所有展品都具有个人的独特表现风格,更特出的创造力和富有生命力,这在创造我们特有的艺术形式方面,是正确和健全的。” 32 致辞中闻不出“南洋”味道。

以上我把片片碎锦连缀起来,从个展到全国美展(1956-1966),十年来民间或官方言论:只提“南洋风格新美术”、“当地独特风格”、“南洋独特之风格”、“马来亚风格” (“Malayan style”)、“南洋艺术”、“马来亚艺术”等,从未提到“马来亚画派”。 那么,我们有“南洋画派”吗?

3. “南洋画派”存在吗?

1985年11月5日,《南洋商报》刊登《张荔英回顾展》,文中说:“我国文化部与国家博物院在1981到1985年之间举办系列回顾展,以褒扬杰出的老一辈画家(刘抗、陈文希、钟泗滨、陈宗瑞与张荔英)对新加坡画坛所作的贡献,并作为后学者的典范……这一批老画家为本地画坛培育了众多接班人,更奠定了具有南洋风情的画风,形成了‘南洋画派’,造成极大的影响力。”33 这段报道的关键词是“奠定”、“南洋画派”,在四大画家的影响下,艺坛产生了“南洋画派”。 “陈宗瑞等之巴厘写生画展,轰动一时,这一展览也被视为‘南洋画派’崛起的一个里程碑。陈宗瑞无疑是‘南洋画派’的一要员。”34也有研究者认为“刘抗的一生与‘南洋画派’的发展紧密地联系一起”。35

一般认为艺术画派必须具备四个条件:(1)一群具共同艺术观的画家,有别于其他画派的表现手法,相近的绘画风格,且有完整严谨的理论体系(2)同处一个地域;具代表性人物(3)具传世作品(4)跨越时代,承前启后的延续性。唯有如此才能把画派的意涵说得清楚,我们具备这些条件吗?我尝试用以下各点说明:

1. 四大画家的风格各异

我采用刘抗的文字说明:“钟泗滨的画风不时在变,从后期印象派,野兽派,立体派到抽象派都尝试过,现在回返抒情的写实,将印尼绘画形式的特征,渗透到油画里去,创立独特的风格。陈文希是中西画兼长的艺术家,他的油画深受布来克(Georges Braque)及克利( Paul Klee)等人的感染,往往有出奇制胜的构思,无论布局,设色,行笔都超然脱俗的手腕,一种大家的风度。陈宗瑞潜心研究水墨与油彩,均获伏越成就常作大幅度的彩绘,结构缜密,敷色沉郁,是他艺术生涯的一绝。我爱过梵高(Vincent Van Gogh)爱过高更(Paul Gaugin)也迷恋过马蒂斯 (Henri Matisse) 崇向开朗毫迈的一路。”36可知四人的画风不尽相同。

为了进一步厘清求证心中疑惑,我访问几位先后担任南洋美专的讲师如蔡名智、黄明宗、方良、曽纪策,他们都认为四大画家的风格各异,质疑“南洋画派”的存在。诗书画俱佳的许梦丰说“印尼画家甚多也甚特出,堪称享誉东南亚艺术第一大国。如果第一代画家以本地事物或风景如画便誉之为“南洋画派”,何其目光之短浅耶?我认为陈文希、钟泗滨、陈宗瑞、刘抗四画师家只当誉为‘新加坡第一代杰出画家’似较贴切。” 美术评论家杜南发的看法是“南洋风格”或“南洋画派”,迄今未止,只是略具雏形,多以地域或物象为据,未真正成型。前南洋艺术学院院长朱添寿也就画派的概念分析:“四大画家的巴厘之旅,随后的画展引起艺术界的注意和兴趣,就有了‘南洋画派’的说法是不妥的。” 担任新加坡美术总会会长11年的梁振康也认为,所谓“南洋风格”在几十年时间内是否成形,或是否形成一个画派,言之过早。37

2. “南洋画派”欠缺完整严谨的理论体系

刘抗留下的文章不少,然而内容繁杂,涉及范围又广,究其缘由或者可借他的话解释:“当地画家只顾埋头作画,而未念及正确理论之建立。”38 细读《陈宗瑞文集》一书,其中如《漫谈中国画与西洋画》,《中西画杂谈》,《略论水墨画之本质与内容——献给墨兰社》以及《漫谈国画》等篇文字不乏闪烁精辟画理,一些作品的题词总结绘画实践,如1950年的《河边洗涤》:“余写南国风光,恒以中法为之,而此帧独以阴阳之法衬托之。盖在初试,然斯法殊乖吾意,今后当不复为之。” 39 遗憾的是缺乏完整严谨的理论体系。

3. 从“四画家巴厘绘画展”推论“南洋画派”不合逻辑

四画家巴厘绘画展从1953年11月6日到15日,于新加坡英国文化协会举行。作品油彩、蜡笔、粉画、毛笔画共一百余帧。印尼驻新加坡领事致开幕辞说:巴厘绘画展促进人们认识巴厘岛人民的生话与自然美景。参观画展者以“西人为主,占百分之六十”,购画者多为西人,最高专员麦唐纳(Malcolm MacDonald)前后参观三次并购买六帧画作,还邀请四位画家到官邸茶叙。画展给社会的观感是“作风新颖,题材特殊,为本坡过去所罕见者”。艺术协会主席基逊禧尔(Dr C. A. Gibson – Hill)赞誉他们各以不同格表现峇厘人文景致。40 我国美术史上四大画家的贡献功不可抹杀,巴厘作品展呈现的是洋溢南洋风趣的南洋风情画,还远远谈不上“南洋画派”。

身为南洋艺术之父的林学大于1958年提出“南洋风的新美术”,它的意涵是“南洋风格”+新元素(作品的时代性,配合社会思潮兼具社会功能)。那么,在稀释了的“南洋风”的前提下推论巴厘绘画展奠定“南洋风格”并发展形成“南洋画派”,是可笑的、不合理的。

为了向南洋美专对本区域的美术贡献致敬,1979年在吉隆坡举行了“南洋画回顾展”,它被视为第一次尝试给南洋美术与南洋风格下定义。Redza Piyadasa 和 T.K. Sabapathy 都为画展撰写文章。Piyadasa 赞扬美专培养了一批“南洋画家”(除了是美专校友,老师或者是学生,也包括私下向美专老师学习的学生)。Sabapathy 认为南洋画家尝试融汇中国传统画法与巴黎画派(School of Paris)于一炉的技法来描绘周边景物。这是上世纪80年代 Sabapathy 在他的文章里所谓的“南洋风格”。 Piyadasa 并没有提到南洋风格,然而其言论却把南洋画家与南洋风格紧捆绑在一起的温床。

T.K Sabapathy 大力提倡南洋风格与四大画家巴厘之旅有着不可分隔的关系。他们“彷如响应了林学大的建议”(按绘画题材应反映南洋的现实,描绘我们土生土长的地方)同往巴厘岛写生。T.K Sabapathy 提出“接受名人的号召”以较强文章的可信度,结果人们有着牢不可破的概念——四大画家的风格来自巴厘之旅,南洋画家也等同南洋风格。41 其实只要读过刘抗发表在《南洋商报》的《巴厘行》,就知道刘抗是向往巴厘的,然而他并无片言只语提到巴厘之旅与林学大的关系!美术史学者 Piyadasa 和 Sabapathy 在还没有机会调查独立前之华文资料的状况下,对“南洋艺术”的脉络发展与核心内涵,一知半解,以致扭曲了“南洋风格”(Nanyang style) 的意涵,也把林学大的“南洋风”稀释了。

八十年代“南洋风”概念被偷换成“南洋风格”,之后论者又演绎成“南洋画派”,这种以讹传讹的逻辑错误越洋飘海远及日本。2002 年福冈亚洲美术博物馆举办“现代艺术 II, 南洋 1950-65:新加坡艺术之旅”,这展出依据 Piyadasa 和 Sabapathy 的看法,结果把“描绘异国情调,异族女性乐园的作品作定义为“南洋美术”,将“南洋风”译成 “Nanyang style ”,四大画家也成为“南洋风”的代表作家……该展不但将“南洋风”定义为异国趣味和乐园风的作品,还把社会写实主义的作品分出去,放在另一类来和南洋风作品相对比……42 殊不知,反映当代社会思潮的创作理念正是林学大的主张。

在我国美术史上四大画家的贡献功不可抹杀,巴厘作品展呈现的是洋溢南洋风趣的南洋风情画,还远远谈不上“南洋画派”。我想:“南洋画派”与“马来亚画派”纯然是论者流淌在心中的美丽憧憬!

4. “南洋风”已经烟消云散

谈“南洋画派”离不开“南洋风”。然而,上世纪60年代晚期随着我国独立与经济步上轨道,反映时代思潮,兼具教育意味,题材敏感的作品,慢慢不为人们所重视。赤艺最后一届年展(1968年)成为绝响,“南洋风”新美术余韵缭绕,之后,渐渐消逝,淡开化去。43 如此,何来的“跨越时代,承前启后的延续性”。 2003年中华美术研究会主办以南洋画风为主题的画展,出版《南洋风作品集》,时任中华美术研究会会长的方良,在画集《序》文中语重心长地说:“现代艺术思潮和社会现实的冲突‘南洋风’是否因缺乏营养而寿终正寝? ‘南洋风’是什么?是否已走入历史?我们要‘亚细安艺术’还是要‘狮城风’?我们对林学大先辈的教诲和发下的作业,我们完成了吗?他在结论时更是毫气万丈,这次画展与期间的座谈会,希望为迄今没有定论的课题寻求辩解,什么是 ‘南洋风’以及今后的创作方向,激发更多同道加入共创‘新南洋风’”。这段话语尤能窥视“南洋风”的窘态!

总结

1950年旅居本地的西方人提出“马来亚风格”(Malayan style)与1954年代林学大在特定时代下提倡“南洋风新美术”( “南洋风” Nanyang feng ),这两者都以塑造马来亚文化作为各族身份的共同文化想象体,然其精神内涵天壤之别,一个是配合殖民政府的意愿,一个是民族自觉性,是走向国家独立的期许。

从美专创校到我国独立,二十多年美术界主要以“马来亚风格”、 “南洋独特之风格”、“南洋风”、“南洋风情”、 “南洋风格新美术” “南洋艺术”,“马来亚艺术”等来描叙兼容东西画技,描绘本地人文景观的艺术现象。60年代我国文化部长拉惹勒南以及文化部次长李炯才都认为“马来亚艺术风格的特性,有待长期的发展才能形成”,那就遑论“南洋画派”了!

80年代在稀释了的“南洋风”前提下推论四个画家“彷如响应了林学大的号召”而有巴厘之旅,之后奠定“南洋风格”并发展形成“南洋画派”的旋风几乎“席卷”了以英文书写的美术界评论。全文追本溯源厘清“南洋风格”(Nanyang style)、“南洋风”(Nanyang feng)、 “南洋画派”(Nanyang School)等词,由于误译、释意偏差、“以讹传讹”以致给读者以及美术史研究者造成混乱的概念。

1965 年新加坡翻开历史新篇章,如果现今的画家仍沿用“南洋风”来描述新加坡的美术作品,是不合时宜的事,它,毕竟是特定时代的产物,是过去式的历史用语而已!我乐意引出陈宗瑞心中流淌过的美丽憧憬:寄望新加坡艺术界能有一日创造一个令全世界瞩目的”星洲画派“。44上世纪70年代,陈宗瑞这句激励画家的祝贺语,历久弥新,在21世纪的今天,愈加彰显启发与价值的意义。

Notes

- 1955年,第一部把缅甸、泰国、老挝、柬埔寨、南北越、马来亚(包括新加坡)、印度尼西亚和菲律宾群岛所在的地区作为一个整体来写的《东南亚史》(D.G.E Hall (1895--1979), A History of Southeast Asia)出版后,今日东南亚的范围才正式确立。引自李金生《一个南洋,各自界说:“南洋”概念的历史演变》,见《亚洲文化》,第30期 ,2006年,页120-121。

- 上世纪20年代,马华文坛的文艺副刊提倡文学应有南洋的色彩。1950年玛戈出版《南洋之美》,集中《南洋之美》,对南洋方方面面给予美丽的赞颂。

- 《南洋风作品集》中华美术研究会出版,2003年,页6-7,页12-14。

- 艺术协会主席基逊禧尔(Dr C. A. Gibson – Hill)也表示 “最终,一个结合东西方绘画特色的 ‘新加坡风格’ 将会出现“,见 “Colony Artists”, The Straits Times, 24 November 1950, 6

- “Aim at ‘S’pore School’ in Art,” The Straits Times, 17 March 1950, 7.

- “S’pore Art Show A Big Success,” The Straits Times, 13 March 1950, 5.

- 同注6.

- 《四人画展观后记》,《星洲日报》,25-11-1951,页5。

- “The Rambutans”, The Straits Times, 24 October 1950, 6.

- 一鸣《华人美术研究会第四届展览参观记》载《星洲日报》,12-12-1939;沙里《漫谈华人美术研究会画展》载《星洲日报》,20-12-1940。

- Noni Wright, “East and West Meet in a Malayan Style of Painting,” The Straits Times, 29 October 1950.

- R.C.R. Morrell, “Towards a Malayan School of Painting,” The Straits Times Annual for 1952, 38–40.

- 欧清池 李一平主编《新加坡华人思想史》,世界文学研创会《研究丛书系列》(10),2018,页134。

- “Chief Aims of British Council in Singapore,” Malaya Tribune, 26 August 1947.

- 1.Dato Sir Roland Braddell 2. Dr C. A. Gibson - Hill 3. Mr Liu Kiang, member of the Society of Chinese Artists 4. Inche Mahat bin Chadang of the Malay Art Class. 5.Roy Morrell of the University of Malaya 6. Tok Khoon Seng Secretary of the School Art Exhibitions. 7.Mr Richard Walker, Art Superintendent. See: “S’pore Art Society,” The Straits Times, 23 November 1949.

- 有关英国“宏大计划”与新加坡艺术协会的关系,见 Seng Yu Jin, “Art and ideology: The Singapore Art Society and the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960),” in From words to pictures: Art during the Emergency (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2007), 10–15.

- 《南洋商报》,1948-2-21, 页 6。

- 《美专十六周年开幕致辞》,《南洋商报》,10-4-1954页 5。又见《南洋美专美展特刊》,《南洋商报》,9-4-1954, 页 8。

- 吴得先《南洋风》,见《南洋青年美术》,新加坡南洋美术专科学校出版,1955 年。

- 姚梦桐《“南洋风”的界说》,见新加坡宗乡会馆联合总会《源》杂志,第114期,2019年。

- 林学大《刊首语》,见《南洋青年美术》,新加坡南洋美术专科学校出版,1955年。

- 《南洋商报》, 25-8-1959,页 6。

- 《南洋商报》, 25-7-1958,页 6。

- 姚梦桐《狮岛的历史印记——一九五十年代的艺研会与巡回美展》,见《怡和世纪》第40期,页106—110。

- 《精美处已臻至境 陳文希画展开幕画展》,《星洲日报》,5-5-1956 ,页6。又见同天 的《南洋商报》,页8。

- 《南洋商报》, 1-7-1957,页 9。

- 《南洋商报》, 29-11-1957,页 6。

- 《星洲日报》,5-11-1958,页16。

- “Minister: Artists have a duty to society,” The Straits Times, 5 February 1960, 4.

- 《南洋商报》,1960-6-2,页6。

- 纪青《让美术摇篮的花朵盛开罢!写在南洋美专廿五週年美展开幕后》,《南洋商报》, 20-7-1963,页5。

- 《南洋商报》,23-4-1966,页16。

- 33 《张荔英回顾展》是本地最后一个表扬本地杰出画家,明年起改另种形式,《南洋商报》,5-11-1985,页5。

- 何家良《画与画理兼优的画家——陈宗瑞》,出版人陈其新,18-12-2010。

- “Yeo Wei Wei, Liu Kang: Colourful Modernist, (Singapore: National Art Gallery, 2011), 8.

- 刘抗《四十五年来新加坡的西洋画》,载萧佩仪编《刘抗文集新编》,新加坡国家美术馆,2011年,页232—233。

- 黄向京《梁振康画展延续南洋风貌》,《联合早报》,8-1-2019。

- 刘抗《廿年来新加坡之艺术动态》,《南洋商报》,1955年7月1日,页6。

- 见唐瑞霞《生机出笔端——陈宗瑞的艺术》,载《生机出笔端——陈宗瑞艺术特辑》,新加坡美术馆,页36—43。

- 见《南洋商报》,7-11-1953,8-11-1953,15-11-1953 以及 The Straits Times, 16 November 1953.

- 参见姚梦桐 胡贵宏《多元对话的反思——解读陈宗瑞的战前作品以及“南洋美术”的界说》,见《生机出笔端:陈宗瑞艺术特展》,新加坡国家美术馆出版,2017年,页 57—72。

- 吕采芷《林学大的艺术世界》,见《传承与开拓》(南洋艺术学院,2011年),页51。

- 见姚梦桐《他们走过的峥嵘岁月——掀起赤道艺术研究会的重重面纱》,载《怡和世纪》第41与42期。

- 陈宗瑞《艺苑拾零》,见《陈宗瑞文集》,页55。

Editor's Note: A version of the Chinese essay was published in the last issue of the Chinese journal 《怡和世纪》in November 2020.