Archipelagic Futurisms

The "archipelagic" is not just a geographic condition of existing among islands. In this article, art historican, critic and curator Carlos Quijon Jr. expands on his idea of "Archipelagic Futurism." As a procedure, "Archipelagic Futurisms" can be used to acknowledge Southeast Asia's complex histories of imperialism, violence and displacement, as well as provide a platform for various imaginations of the future that are based on archives, methods and practices shaped by the condition of being archipelagic.

Date unknown

Etching, 201/8 × 165/16 in. (51.05 × 41.4 cm) The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949 Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

As a conceptual configuration, I see “Archipelagic Futurisms” as an opportunity to unpack discourses and methodologies that speak to the categories of the archipelagic, futurisms and the curatorial: In what ways does the archipelagic complicate notions of futurisms? How are futurisms imagined in the archipelagic context? How does the curatorial become an exceptional context in performing the possibilities of “archipelagic futurisms”?

The archipelagic in this framework is not just a geographic condition of existing among islands, among bodies of land and water. It is a configuration of space shaped by the necessarily fraught narratives of affinity that come out of the dispersals of the archipelago; the tenuous but equally tenacious connections between distant places shaped by imperial networks of violence and displacement; and the shared experiences of engaging with these histories and archives in the contemporary time as they mutate into geopolitical sites of friction or common ground.

In delineating the archipelagic, I mine the existing scholarship that explores its implications relating to the thematics mentioned above.

Working on the Spanish Imperial Archipelago, the scholar Javier Morillo-Alicea presents the archipelagic as a way to account for “horizontal connections that existed between the colonies of a single empire.” For him: “[t]he country-metropole focus…has understood the workings of colonial knowledge in a largely vertical manner, i.e., through attention to the relationship of a metropole and one of its colonies.”

The work of Yolanda Martínez-San Miguel expands on this lateral procedure, this time focusing on the Caribbean archipelago. For Martínez-San Miguel: “archipelagoes seem to index the tension between imperial economies (Spain, the Viceroyalty of New Spain) and colonial borders (the Canary Islands, the insular Caribbean, and the Philippines).” In this account, while the imperial archipelago is shaped by the centrality of imperial power, it also constitutes a horizontal nexus: “a unit of geographical meaning capable of reconnecting the Caribbean with other systems of islands that have been imagined and reimagined as colonial archipelagoes or overseas possessions of European and US-American empires.” She concludes: “archipelagoes are no longer distant overseas possessions but are now transformed into clusters of islands with anomalous political states that defy the normativity of national and transnational imaginaries.”

Looking at Sinophone literatures across Southeast Asia, literary historian Brian Bernards forwards the archipelagic potentialities that Nanyang writing embodies. For him, it embodies “the ongoing formation of multisited, multiethnic, and multilingual cultures.” For Bernards, “[b]y sustaining, establishing, or simply imagining new relations between islands (Borneo and Taiwan), capitals and port cities (Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, and Hong Kong), or regional centers (Hat Yai and Penang) that transcend national boundaries in the archipelago, the postcolonial Nanyang becomes an alternative network of affiliation to circumvent official national policies and dictates.”

The archipelagic is a dispositional space shaped by both the histories of the colonial and the contemporary. It ranges from the imaginations of the Ryukyu islands in the East Asian Sea that historically connect islands beyond the ambit of national formation from Okinawa to Taiwan; to how Manila, Hong Kong, and Shanghai made use of telegraphic connections to create a network of observatories that looked out for weather disturbances in the South China Sea; to the forced exile of intellectuals from Java to Jaffna and further out to South Africa, creating a community of Muslims in Cape Town (the Cape Malays); to narratives of Malayan exceptionalism that extend from Taiwan outward to places as far as Madagascar; to Sinophone migrations and literary cultivations in what we know as Southeast Asia; to China’s contemporary forceful incursions onto the Spratly Islands; and most recently to innovations and changes steeped in archipelagic imaginaries, such as Nusantara in East Kalimantan as the new capital of Indonesia and the creation of the Kau Yi Chau Artificial Islands in Hong Kong; and to the hypothetical String of Pearls, a network of communication lines and military and commercial facilities cultivated by China in the Indian Ocean across ports and islands, extending from the mainland to the Port of Sudan in Africa.

Considering these case studies then, the archipelagic offers not just an entry point to think about relationships between spaces, but also a way of thinking about time in more preposterous terms. The term is from cultural critic Mieke Bal through which she proposes an interventive rethinking of historical time. Thinking preposterously “neither collapse[s] past and present, as an ill-conceived presentism, nor objectif[ies] the past and bring[s] it within our grasp, as in a problematic positivist historicism.” Instead, the procedure “puts what came chronologically first (‘pre-’) as an aftereffect behind (‘post’) its later recycling,” which she nominates as “a preposterous history.” The relationship between the chronological past and the present (or the more recent past) is not unilinear, and continually inform each other in a multidirectional traffic.

As a platform, “Archipelagic Futurisms” is interested in how futurist imaginations are embodied and envisioned through continuities and latencies that may be drawn out from archipelagic dispositions. This is a futurism that necessarily shifts and moves across the varied contexts of archipelagic dispersals, displacements, and through the rather unsettled distinctions between temporal markers of the pre-, the post-, and the neo-.

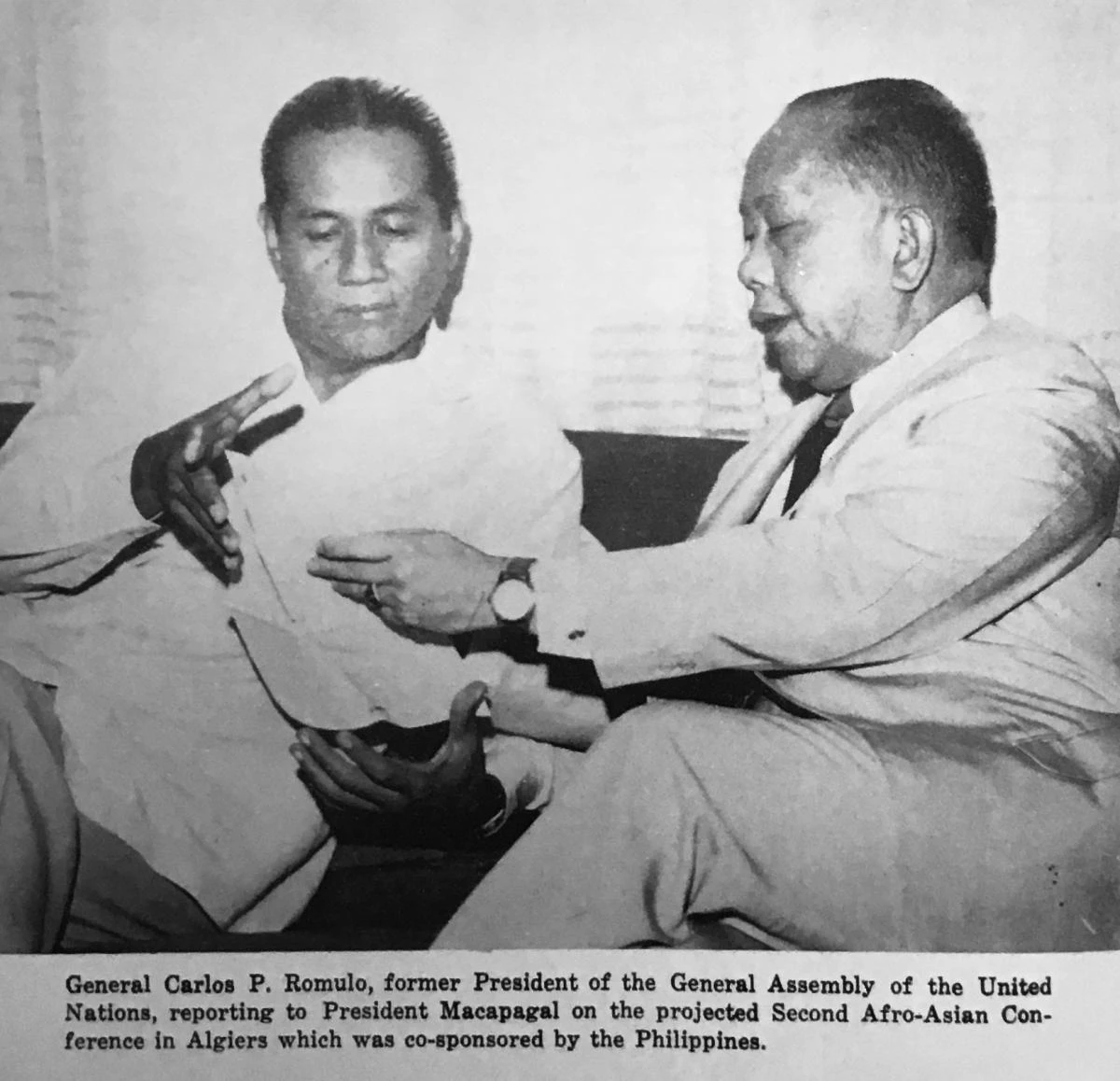

I imagine the curatorial project Afro-Southeast Asia: Pragmatics and Geopoetics of Art during a Cold War, a traveling and iterative research and exhibition project I co-initiated with Kathleen Ditzig in 2021/2 as an initial fleshing out of these ideas. For the exhibition, I did research on Maphilindo (an amalgamation of then Malaya, Philippines, and Indonesia), an imagination of Southeast Asia regionalism based on a pan-Malayan ethnos, which became a way to map out certain coordinates and trajectories that elaborate on the complex dynamics of solidarity in the context of Cold War politics. Maphilindo situated solidarity well within the multiple interfacings of neo-colonial entanglements of sovereignty and an imagination of a post-Cold War world order by way of the United Nations.

The exhibition explored the repercussions of this 1960s imagination in the contemporary time, with the hegemony of China and the usually unquestioned rehearsals of Afro-Asian discourses in historical and curatorial endeavours. It played out Bal’s “preposterous history” in the way it annotated contemporary imaginations and futurist speculations by way of agitating the sedimented histories that we now take as unproblematic and uncomplicated. The futurist moment does not rely on a scientific-developmentalist horizon, but on a more poetic reconsideration of episodes in history which signal possible recalibration of our very imagination of futures through the recurrence of latent or previously inchoate discourses or ideologies.

Informed by these parameters, “Archipelagic Futurisms” is an attempt to discern historical, contemporary and futurist possibilities of compositing histories of knowledges, lifeworlds, ecologies and art/artmaking in order to conceptualise an “archipelagic practice” and explore how this practice may lead to a particular kind of futurist imagination. Placed in the context of an expansive Southeast Asia, the platform is imagined to be a series of exhibitions and publications that propose entry points into speculating and anticipating futurist possibilities from the archives, methods and practices that shape and are shaped by archipelagic conditions.

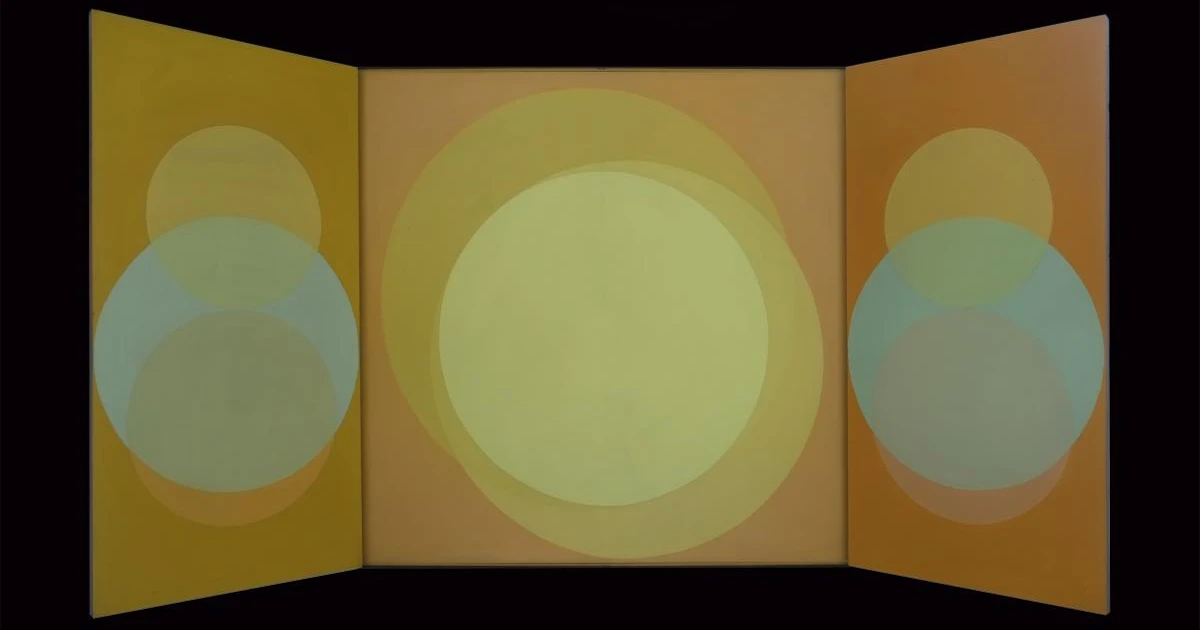

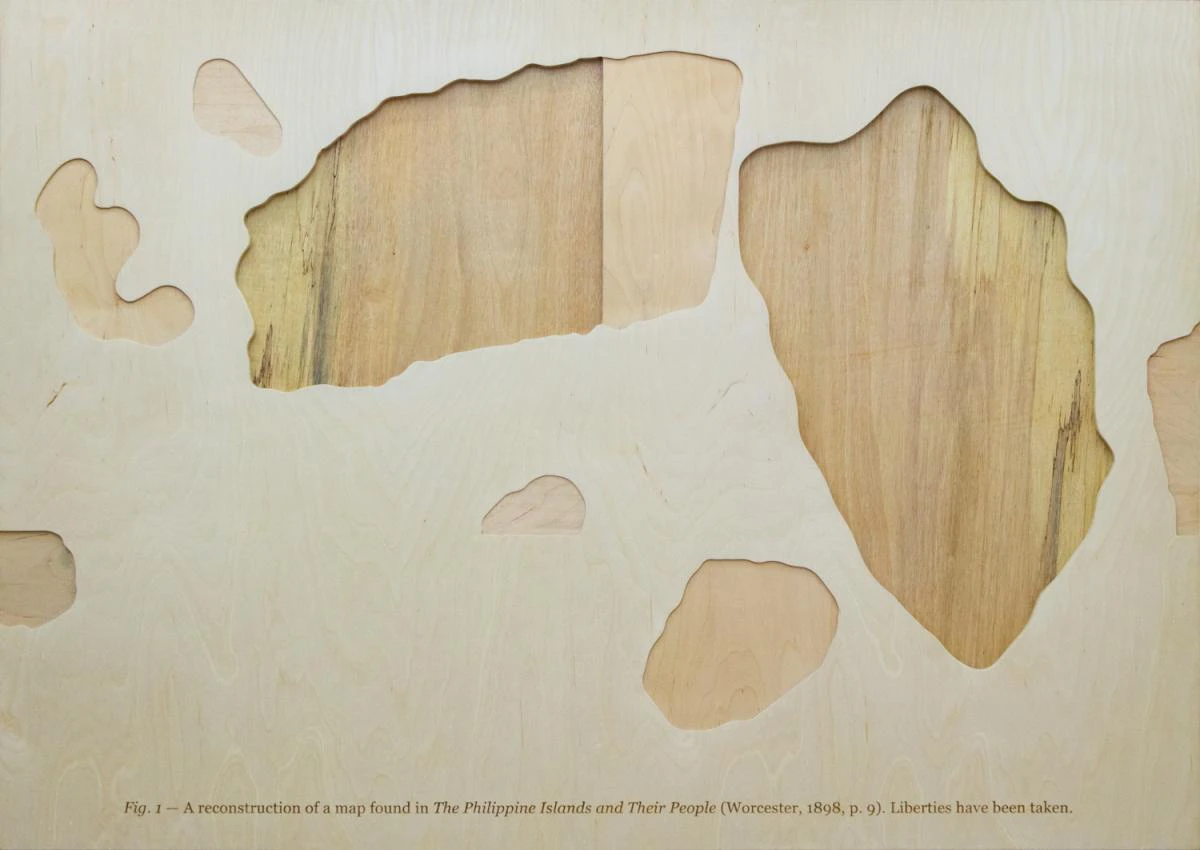

The first iteration of the exhibition series, titled and land erodes into, was developed for Calle Wright in Manila. It presented works by Nice Buenaventura (b. 1984, Philippines) and Fyerool Darma (b. 1987, Singapore). What is interesting about this first iteration is that it presents, in one exhibition, the already existing threads of research that Buenaventura and Darma have been unravelling in their own practices. In this sense, and land erodes into alludes to existing conceptualisations of archipelagic practice and refines its stakes by nominating these practices as futurist.

The exhibition involved questions of materiality and abstraction, the latter of which is shaped by the context of the archipelago and its attendant materials and conditions of materiality. Darma uses as the basic unit of his abstract works strips of vinyl, an industrial material that proliferates in Southeast Asia, known for its widespread applications due to its ability to withstand weather extremes. On the other hand, Buenaventura draws out an idiom of abstraction from photocopying, a ubiquitous means through which knowledges, especially in the Philippine context, circulate. Their works present an attentiveness to materiality: grain of wood, gradations of graphite, shiftiness of sand. There is also a keen attentiveness to the afterlife of material ephemera: from national tourism campaign materials or even materials discarded from other artistic projects.

Another layer to the exhibition is the use of technology, or at least the allusion to how technology materialises social worlds. In one of his works, Darma appropriates and remixes idioms of advertising with parameters of the internet age that have brought about novel ways of assessing quality of life, such as bandwidth, as well as the technologically novel ways in which we create worlds and connect with each other. In another work by Buenaventura, the artist presents a composite imagination of the climate crisis from crowdsourced footages found on social media.

Another layer is the circulation of genres and forms. In Darma’s UTC / Heaven is in Cloud System (2023), he works with a number of collaborators, remixing the musical genres of the Mandarin techno and dance manyao, Indonesian club dugem and Bisayan EDM budots. In another work, the artist draws out speculative histories of nusantara through the poetic form of pantoum, which in this particular showing he extends to the Tagalog form tanaga.

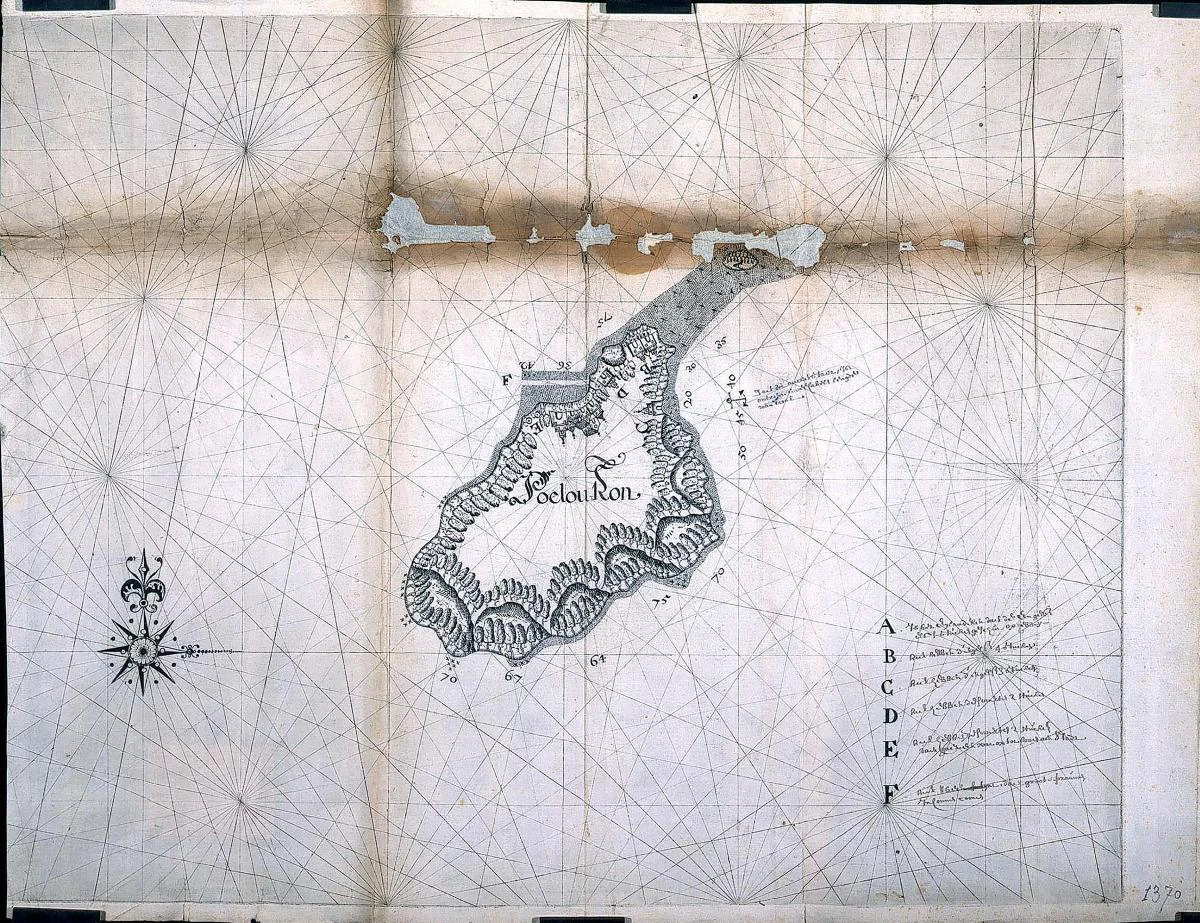

Two other iterations of the exhibition series are being developed at this point. In the iteration that will happen as part of a residency I am doing in New York, I am working with Malaysian artist Ahmad Fuad Osman (b. 1969, Kedah). Titled Archipelagic Alchemy, the solo presentation is based on Osman’s project centered on an episode of colonial history involving the exchange of two islands between New Netherland (present-day Manhattan) and Pulau Run (one of the Spice Islands, present-day Maluku Islands). The exchange of ownership, wherein the English-owned Pulau Run was exchanged for the then Dutch-owned island of Manhattan took place in the 17th century. It was one of the provisions in a treaty signed by the Dutch and the English, ending the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

Another iteration will focus on how weather, as an affective and political experience in Southeast Asia and its nearby islands, may draw out historical, metaphorical and technological affinities between islands. I am working with a space in Hong Kong in thinking about how futurisms may be derived from the history of meteorology in the vicinity of the South China Sea. In the 19th century, the network of observatories in the South China Sea—results of colonial infrastructure projects— created a system of early warning systems, connecting the region through telegraphy and emerging scientific inventions. One such invention was the barocyclonometer developed by the Jesuit priest, meteorologist and director of the Manila Observatory José Algué. This hurricane detection device was used by the US Navy at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War.

With Southeast Asia’s “instability as a regional concept and daunting diversity,” particularly considering its maritime geographies, I consider “Archipelagic Futurisms” as an earnest procedure to acknowledge the complex histories that such an expansive region embodies. The reworkings of the archipelagic as a dispersive mode of thinking and practice offers us atypical considerations and necessarily plural notions of futurist inflections. I see “Archipelagic Futurisms” as a method that allows these kinds of erratic compositions to speak to imaginations of the future across varied tenors. From this vantage, I am proposing to reconsider ideas of futurisms as ideas of another time, in which thresholds of rethinking the composition of the world reveal themselves and people are forced to reimagine our places in it.