Bumi-antara: Other Perspectives on Pattern-making and Mapping the Future

Kathleen Ditzig rounds up this Bumi-Antara takeover of Perspectives, demonstrating how the discursive threads and engagements underlying curatorial work go beyond the institution of the museum. With the increasing prevalence of AI technology in our everyday lives, she also discusses how research into Southeast Asian Futurism can help us grapple with the new patterns and "maps" that computational logic is now generating.

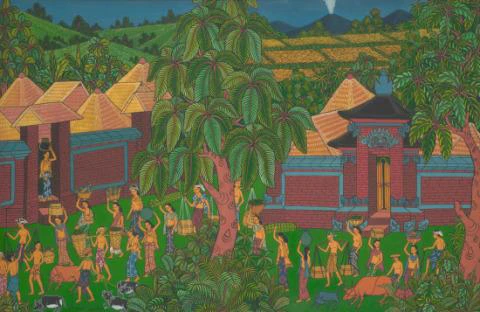

Ubud Bali

Undated

Tempera, 89.3cm x 136 cm

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board, Singapore

One of the Gallery’s aspirations for this Bumi-antara takeover of Perspectives is to provide a peek into the museum—a lens into embryonic research and projects beyond exhibition-making that bubble and boil under the hood of the institution, and the development of the multitude perspectives on the rich collection of Southeast Asian art. In this spirit, Qinyi, Anissa and I have sought to pull the proverbial curtain aside on the community of thinking and discursive collaboration that underlines an expanded curatorial research project. Our inquiry into the histories and aesthetic aspirations of Southeast Asian Futurism ties to a lesser-known history of global futurology, based in Southeast Asia and developed through the work of Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana. All of this will ultimately take shape in an upcoming research publication in the coming years.

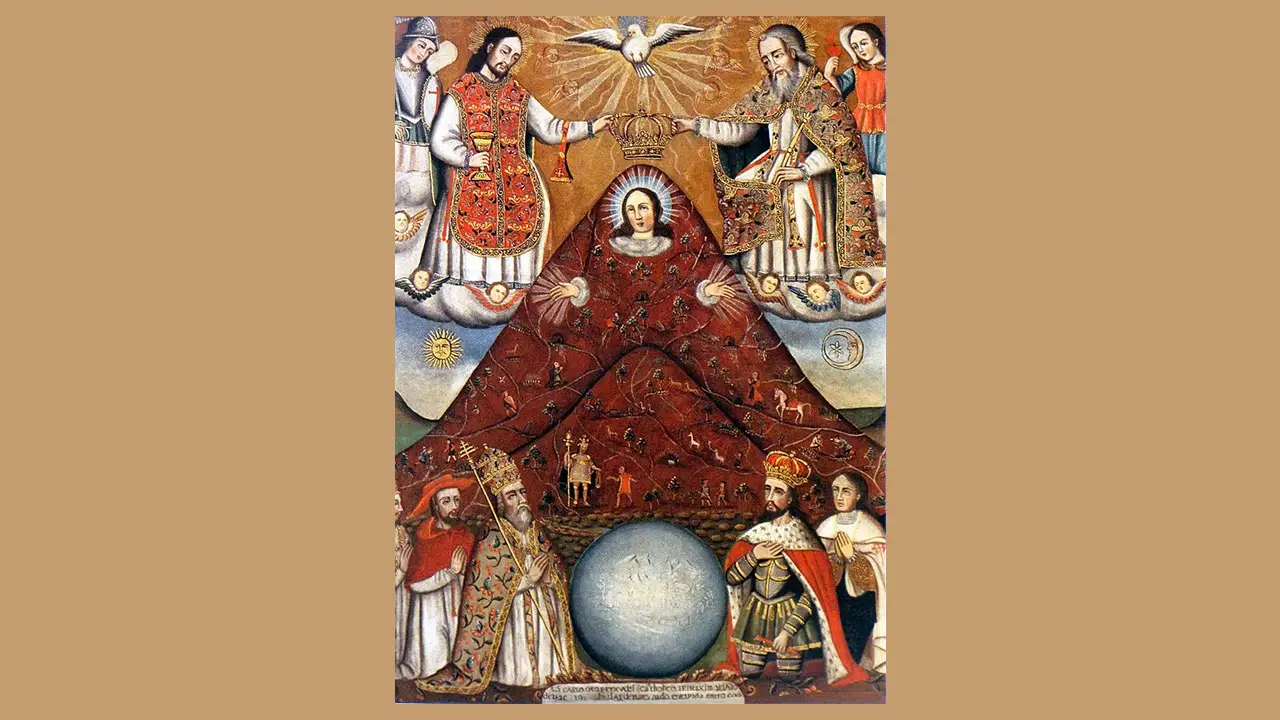

This project of defining Southeast Asian Futurism is a fundamentally historical project as we trace the idea that artworks by artists from Southeast Asia offer “a cultural pattern.” The byproduct of the region’s numerous civilisations, crossings and translations, this pattern can provide a vision that will seed the values of a collective human future in its audience. Working with thinkers of the region, we have sought to produce more varied and multidisciplinary approaches to define futurism from the region, across artistic and curatorial perspectives. This intervention into Perspectives has pulled together different visual systems that conceptualize the (multiple) horizons of the future using the national collection’s wide ambit of modern and contemporary art practices.

Such articles have been presented alongside research by the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale (SMB12) artistic director Rachael Rakes and associate curator Sofia Dourron, who have argued for abstract forms of data and representations of cosmological systems as parallel forms of map-making, highlighting how pattern-making can be alternative knowledge foundations. Their theme for SMB12, THIS TOO, IS A MAP, reveals how pattern-making and “stylistic motifs that lead to common understandings” can be understood as counter-mapping or forms of alternative map-making that throw into relief underclasses, non-human beings, less visible extractive or data-driven systems (both overground and underground) that evade the aesthetics and knowledge of Western dominance and colonialism. In their interview with Singapore artist Fyerool Darma, Rakes and Dourron show that pattern-making is a politic of retro-futurism.

This Bumi-antara takeover, which seeks to reveal the tendrils of cross-disciplinary discussions and affinities of considering the futures of Southeast Asia, is preceded by several collaborative initiatives: one with SMB12, and another with the External Assessment Summer School. The former has culminated in an essay by myself and Anissa Rahadiningtyas in SMB12’s catalogue entitled “Countermapping Futurism: Bali and A Cybernetic Primitivism.” The External Assessment Summer School, a pedagogical program held with the support of KONNECT ASEAN in August 2023, yielded a thoughtful reflection by the participants, Diandra, Akmal, and Angelica from Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB – Bandung Institute of Technology), where the workshop took place. The programme was developed for ASEAN cultural policymakers and students looked at different forms of forward-thinking practices in Bali, Majalengka, and Bandung, where we collaborated with artistic collectives such as NUSA CMYK and Jatiwangi Art Factory and an art school, ITB.

By featuring these different text types (research pieces, interviews, field notes and more), this Bumi-antara takeover of Perspectives is a loose map of the discursive threads and engagements underlying curatorial work that are not always contained within the singular frame of the museum or institution. More than just going beyond the confines of the museum, Bumi-antara also makes nascent research related to Singapore’s National Collection and the region’s histories accessible to the public as they develop. Sharing an ethos of meta, parallel and practice-based discussions, the two research projects THIS TOO, IS A MAP and Southeast Asian Futurism point to a zeitgeist of critically engaging with pattern-making, alternative knowledge systems, and visions of the future that speak to the urgencies of our present and resist the colonial and extractive logics of global capitalism. By being alongside and dissolving into other contexts, their research inquiries have also been a process of seeking affinity and shared logics beyond history and geography, and solidarity in difference.

Looking towards the immediate future, Bumi-antara also speaks to a wider and urgent field of inquiry on pattern-making as a form of political logic. Earlier this week, AI Singapore announced Sea-Lion (Southeast Asian Languages in One Network), an open-source Large Language Model (LLM). Trained on eleven major languages used in Southeast Asia, the multimodal speech-text model is meant to be representative of the region’s cultural and linguistic diversities. The increasing prevalence of artificial intelligence (AI) as infrastructure that defines our everyday—and the value of knowledge and data in society—has raised questions about the bias of knowledge systems and languages upon which these governance models have been built. What are the patterns that these governance models, schooled in Western system systems of knowledge, producing? Of these, how many are there that we do not see?

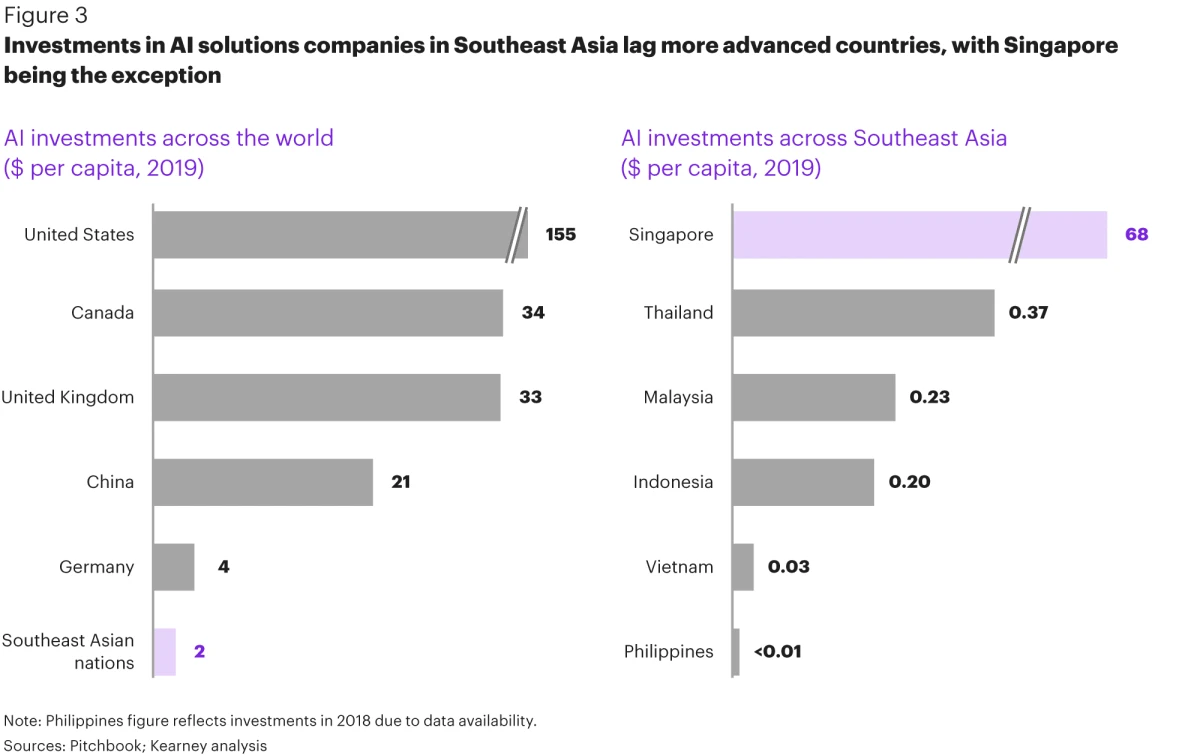

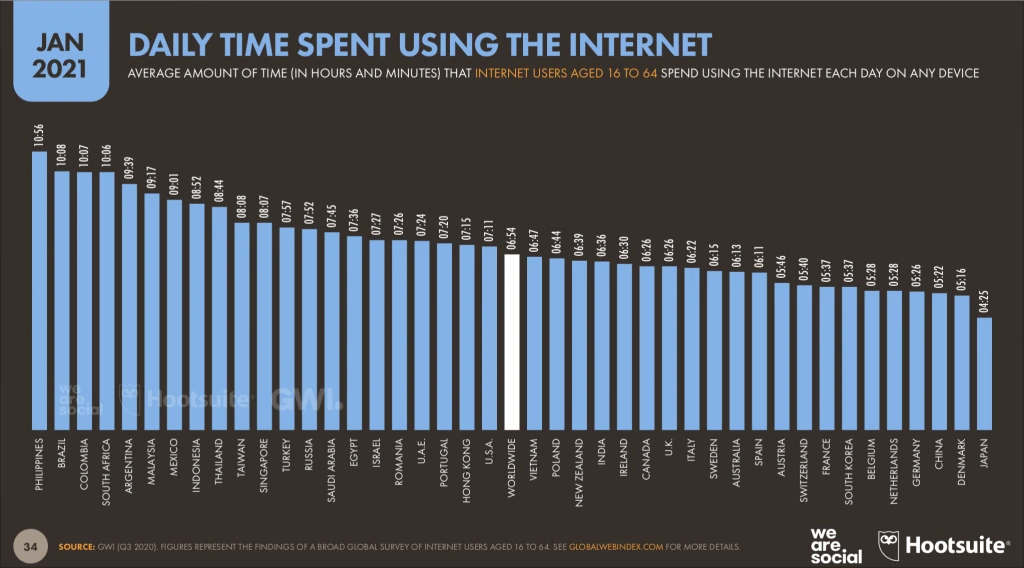

With Southeast Asia’s diversity of languages and cultures, the answer has been to produce new tools based on language systems and nuances found in the region. This is critical given that while Southeast Asia accounts for only 2% of global investments in AI, its nations are among those that produce the most data in the world.1 Clearly, AI models promise to have considerable influence in the region, with many models being owned or constructed by Southeast Asian nations or companies. While Sea-Lion seems to be an answer to this, it is imperative that we question what patterns are being left out by computational logics. A computer is a type of map, producing a very specific form of intelligence. The recovery of a history of Southeast Asian Futurism as part of a global history of futurology and cybernetics‒the roots from which AI developed—is as valuable as inquiries into counter-mapping and pattern-making. In this way, these projects looking into Southeast Asian Futurism aim to ensure the preservation of alternative knowledge systems that form the seedbeds for alternative visions of our shared futures.

Note

- Soon Ghee Hua and Nikolai Dobberstein, "Racing toward the future: articial intelligence in Southeast Asia," Kearney, posted 7 October 2020, https://www.kearney.com/service/digital/article/-/insights/racing-toward-the-future-artificial-intelligence-in-southeast-asia; Kristie Neo, "Southeast Asia: Digital Life Intensified," We are Social, posted 8 March 2021, https://wearesocial.com/sg/blog/2021/03/southeast-asia-digital-life-intensified/