Interview with Fyerool Darma

Rachael Rakes and Sofía Dourron of the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale interview Singapore artist Fyerool Darma on his polyphonic practice. Fyerools' works resist the singular progression of history, and rebelliously insist on the illegible and on speaking collectively at the same time.

Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford Oxford. Source: Bodleian Library MS. Pococke 375: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/ced0d8bd-1019-4af2-9086-e411115f1507/

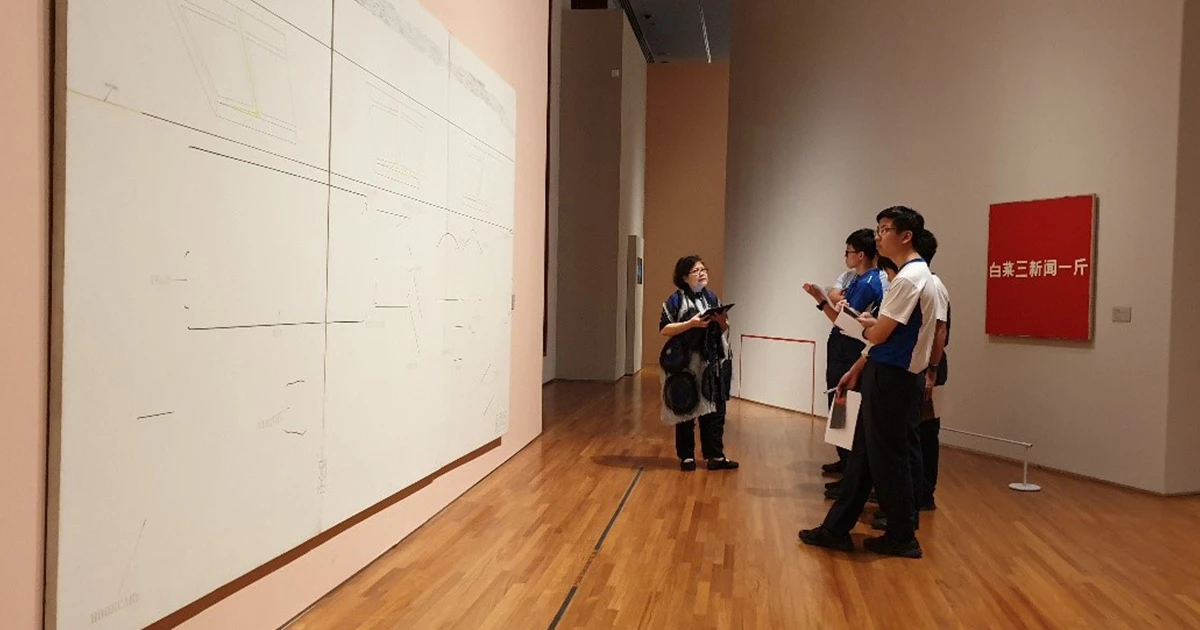

Expanding on the 12th Seoul Media City Biennale (SMB12), THIS TOO, IS A MAP, Rachael Rakes and Sofía Dourron interview Singapore artist Fyerool Darma on his polyphonic practice that resists the singular progression of history. Fyerool’s work resists the particular resolutions, aesthetics and imaginations of an advanced technological human future all nations and people should pursue. His work at SMB12, l♥ndsc_₱€$s (poienxcinoti) (2023), is produced by a community of artists and a collection of art. It features rawanxberdenyut, Aleezon, Lee Khee San, Autaspace, CC1, Dahlia, Alawiyah, 风 and Lé Luhur from NUS Museum's South and Southeast Asia Collection. In unpacking the different layers of this work and Fyerool’s practice, Rakes, Dourron and Fyerool unveil the complex legacies of pattern-making in cartography—such patterns have left their mark on the knowledge systems perpetuated by museum collections, and contine to define our present and future. Ultimately, their conversation points to the urgencies of artistic practices like Fyerool’s that rebelliously insist on the illegible and on speaking collectively at the same time.

RR: This issue of Perspectives deals with intersecting probes around retro-futurism, in particular, recovering the pasts futurisms of Southeast Asia, as well as looking at how the Western surveying and mapping of various parts of the world foreclosed countless modes of future-thinking. So maybe we could start off by discussing the multiple notions of futurity in your work?

FD: For me, futurity is always a constitution of reading time and its contingencies. From where I sit, time is like a reverb, with sound and echo growing alongside one another. Despite the chronological disjunctures, past-present—or the then-here-now—kind of move together at any moment, shifting into different social venues. This perspective was informed by multiple stories, personal experiences, listenings and the act of eavesdropping as I moved between grounds, spaces and places. And when I travel via land, sea or air—and even in sleep—I am constantly shifting between time zones. This idea of time is also informed by spiritual understandings, and what I like to think of syncretism. I grew up hearing and encountering multitudes of voices embedded within my head, ina multitude of accents—telo and slang too. I have lived with the Gregorian calendar, lunisolar calendar, lunar calendar, the Hijri calendar and the digital calendar. These are interwoven with an understanding of shifting moon patterns, and amidst all this, the tenderness of ancestral time.

RR: Would you call this then a temporal syncretism?

FD: Temporality is not fixed, yeah? Time is a construct and guide instead of a concrete barometer that one follows. But of course, within the context of Singapore, as with elsewhere, time is understood as a rule of efficiency and inefficiency. Hence its monotonous linearity.

SD: I think this manifests in your work in different ways: in the techniques that you use but also the materials and the overlapping of times and scales. Maybe you can elaborate on how these materials and ideas show up in your work.

FD: It’s a constant cycle of exiting and entering, re-scaling and de-scaling, and the skewing of identifiers. The goal is to shift their intended functions so that the components of the work can read as time-stamps: the patterns, when one considers how it was made, can be read as a technique; the materials, which were extracted to be utilised, serve as texts for technological growth, degrowth, or even its dormancy. These ideas are displayed through the assembly of motifs and leitmotifs; the materials, in their raw or synthesised moments; the series of screenshot, where the salvaged textiles are sliced and rewoven with easily found materials (polyvinyls, polycotton threads etc.) that are off the shelf or taken from construction areas (xylene, polypropylene tapes); the drawings or carvings on surfaces; and that which dangles (ropes) and is suspended. They are all interwoven, ziptied, screwed on or tied to literally present the entanglements of aspirations and the contradictions of a hyper-consumerist society. These are elements and matters that are either hidden or left dormant within certain institutions due to their sus provenance. They are markers of different periods of time, stemming from a historicised or speculative summary.

I first encounter them on the screen, and then beyond that, in the streets and in the home. They, in turn, traverse heritage, the personal and collective, and the subcultures that draw from them. Often, several motifs or patterns are present at the same time. How one can read them is to see them as markers, or even entrances, into understanding the technologies used in creating these motifs or patterns. I was thinking of how they arrived at these vicinities. Historically, this was not just by way of trade but by forced inclusion, and many a time through expositions as well. Hence, it becomes a question of that persistence, and how eventual decay takes place not because of potential affinity but of the constituency of one's perception of the identifiers. It is a mode of working that reflects on the access and inaccessibility that I encounter even within a place familiar to me.

The first layer of patterns I used in the work for SMB12 came around from an earlier project at NUS Museum, After Ballads. It was then that I encountered the textile pelikat (pink and blue). Its provenance was unknown, but it got me thinking of painting, gridsmovement and shifts The grid reminded me of a map. It was housed in a museum, and like other museums, questions of ethnography, anthropology, archeology and their legacies reverberated—the anthropological body is a data body even when one refuses to claim it. I realised what I was experiencing was a constant state of being in between—a refusal as much as it was an embracing of it.

Having them assembled all in one space and drawing over them with a knife was a way to interact with them and bring them into the conversation. The patterning of the various textiles was conceived after my computer crashed— it was a screenshot of that failure to compose. It reflects the constant erasuresand generative nuances. Constant because patterns were part of a large industry: the textile industry. At the same time, I am also thinking about how these different entrances and exits is a constant need, and indeed constitute a constant flow, with the changes of technology. I guess that mix explains that inquiry.

RR: Yeah, it could be. Could you also speak more directly about the way that you mix several kinds of histories and heritages via patterns and how this practice changes meaning?

FD: So the vinyls were informed by specific motifs that were woven by several hands and (intellectual) influences that had been compressed to jpegs taken either from stock images or archives that point to affinities between Tamil Nadu, China, Bali, Batam, Pattani, Palembang, Scotland, Terengganu, Johor, Mindanao, Java, Singapore, Sumatra and Tanjung Pinang (to name what I remember). I’m referring to brocades, songket, etc. They motifs come from different time periods, and are residues of histories and legacies from the triassic, to the stone and gilded ages of Srivijaya, Langkasuka, Song and Jambi, to the Bujang Valley—they are collections of varied interpretations, akin to synthesised forms from fossil fuels. There is the motif of the young bamboo, stylised from the Bawean, Bugis, Palembang and Minang, the plain grids were from Tamil Nadu,and the dazzle camouflage employed by the allied forces during World War I; the cut motifs or diagrams were amalgamations generated from my muscle memories after I had processed the motifs, diagrams symbols and signs encountered through my affinities, ranging from custom culture, leets, syair toto, chinoiseries, geometries to the silhouettes of emojis and wingdings.

It was during the process of translating them from thought to the surface that these meanings shifted and drifted from their sources. It was not an exercise in seeking a new mode but rather, a way to find possibility after all these overloads, to retain the opacity if I may, despite the density of all these matters. I have noticed that the rendering of the motif over the patterned vinyls allows for a shift in reading not just of the pattern, but also of the stratas of its influence and what could come after that. It was intuitive at first—the arrangement and re-arrangement (of vinyls)and the acts of slicing or cutting upwere forms of annotation and collaboration;the re-scaling and shifting of it to another place would take place after that.

SD: You work with different shapes present in various patterns—for instance the triangle that refers to looking at one's life in a humble way—or other forms that could point towards other ways of looking at the city and other systems. So, there are a lot of implications in the patterns you use and the way you manipulate them that have to do with the ways that we perceive the world.

FD: This leads directly into the marks left on the ways that we see the world. By remixing and oversampling these different ways of seeing and thinking, you're creating alternative ways of perceiving one's lives, but also the city, the territory and even history itself.

I think one could allude to a constant re-shifting, if I may put it in that sense. Take the grid structure for example—we understand it as fixed right? I’m curious how can we prod the shift in our thinking with updated forms. It's still an aspiration, a potential.

RR: What I talk about in the essay that I contribute to this project is about how maps are visual culture: all maps can be seen as simply as that, even if they're weaponised otherwise. In a case like Singapore, as with many others, this extremely particular formation patterning emerges. Again, there will be one that won against others for various reasons, or was more powerful for various reasons at a certain point time. I guess when I see that reading in your work. there's a fine line between what seems to be technical or scientific and what seems to be in the realm of the visual or the creative or artistic. Where's the line between the technical image and visual heritage?

FD: It’s entangled from the beginning of its knowledge. Where the technical image does not inform the heritage, and vice versa, rather, it grows together, alongside, despite the discordances, despite the multi-mis/readings of it. The exercise was this – To not separate or categorize them, but rather draw and think with as you witness their nuances. The technical moment in the exercise was informed initially from the weaving techniques, through the act of weaving in the physical, where it's meditative, yet thoughtless, it's a metaphor in literary or conceptual approach in artmaking. Later it was informed from the gestures in dances like the boek, after which the feng as orated or boom, or written in a poem. The line of the visual heritage is constantly in the non-tangible, like the installation period, any moments before the display took place – the process where only an intimate few witnessed, here, the exhibition making crew. The technical image or images, are the carvings or renderings flattened onto the surface or that suspended from the wall, these are residues of that unrecorded performance.

RR: It would be great from here to speak about collectivity and whether in your or material collectivity, we can discuss that in your work.

FD: The idea of collectivity is really important for me. Growing up in a big family, interruptions are constant, and we were all constantly cooking, washing, cleaning and living to make a series of events together, not for profit or as a business, but as a communal approach in making and creating something together. Within that process, there are also the disruptions and interruptions of varying opinions—and this is where the non-linear approaches that inform me come from. This is also where contradictions stem from.

The works are always a result of varied individuals that come through so that we can make the works together, with their chosen display names. I use the time to also understand different approaches so that I may unlearn and relearn nuances that I was uncomfortable with. It acts as a working group to understand rhythm and music, to readings or misreadings of poetries and philosophy; there is the knowledge that are informed by these collaborators, ranging from fashion, music, to exhibition-making; we have house painters, mememakers, and also a delivery rider, these are people that someone within the arts might consideroutsiders. It’s like a series of informal sessions of note- sharing. There is a commitment to sit with, converse with and think with the talents. As for the materials, it’s an assembly of matters, an inventory of fossilised materials, synthesised through moments of output, beneficial or otherwise, and sometimes even discarded or with questionable provenances. Zooming out from this, there was an intentionto constantly map, including mapping the various facets of talents to learn from and with, and to play, dance or sing with. This approach was informed by speculations from an earlier project that looked into the works or writings of Munshi Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, where I became fascinated at how the writings presented a map of people who signed off as him for unrecorded or unknown reasons. I see it as a map of friends and students, whose occupations varied, ranging from theologians to surveyors, transcribers and individuals who just wanted to write.

SD: I was thinking how allowing for this to happen, and having this network of collaborators as foundational to the work, shows up in the images and in the materials themselves. It feels like maybe your work is creating a space or an organism for dissent or contradiction to happen: in the ways that you allow for collectivity to happen, but also in the way that you use materials and histories that can sometimes contradict one another. So in that way, the work is not in unison, as you said; it's not smooth. It's very loaded and allows for all of these things to clash. I was thinking about the way those processes also contradict the way in which maps are usually conceived of as a rational and truthful representation of the world. Maybe your work does the opposite or goes against the grain of that aspect of mapping, creating a territory full of alterity.

FD: Thank you, I think of it as a reflex, deflex and a flex too. I guess I am always sus when encountering the advancements of technology or the demands of it. My first encounter with a map was actually of one done by a scientist and astrologer, al-Idrisi. It was interesting that it looked like an ![]() —maps were and are about perspective, vision and thinking. It’s personal and it connects yet disconnects. It also projects a biasness of view, viewing and the viewed. As with the current day, the maps we witness are accumulations of the several perspectives by named and many more unnamed individuals. Is it then a synthesis of the various minds (human or non-human alike) that clashes?

—maps were and are about perspective, vision and thinking. It’s personal and it connects yet disconnects. It also projects a biasness of view, viewing and the viewed. As with the current day, the maps we witness are accumulations of the several perspectives by named and many more unnamed individuals. Is it then a synthesis of the various minds (human or non-human alike) that clashes?

After that first each encounter, there's always that sus point in time when looking at maps: Is this real? Is this not?