History Students Ask a Curator | Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960–1990s

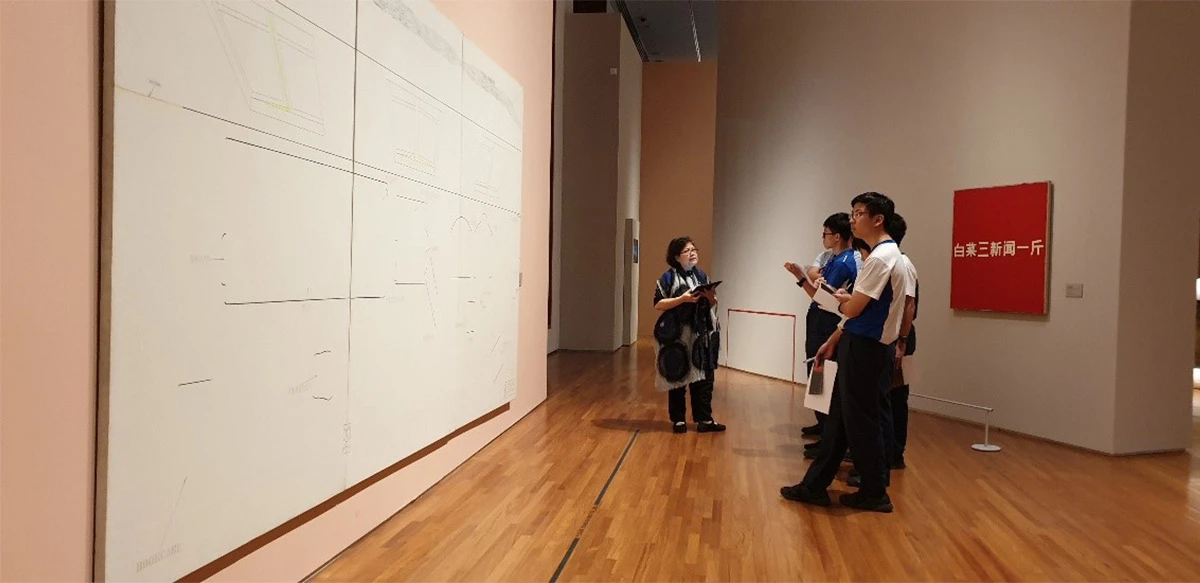

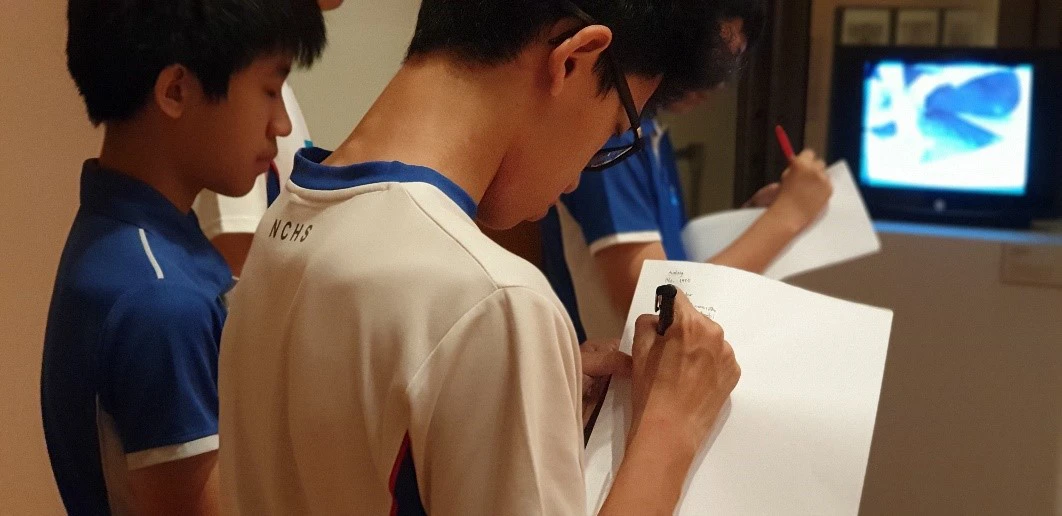

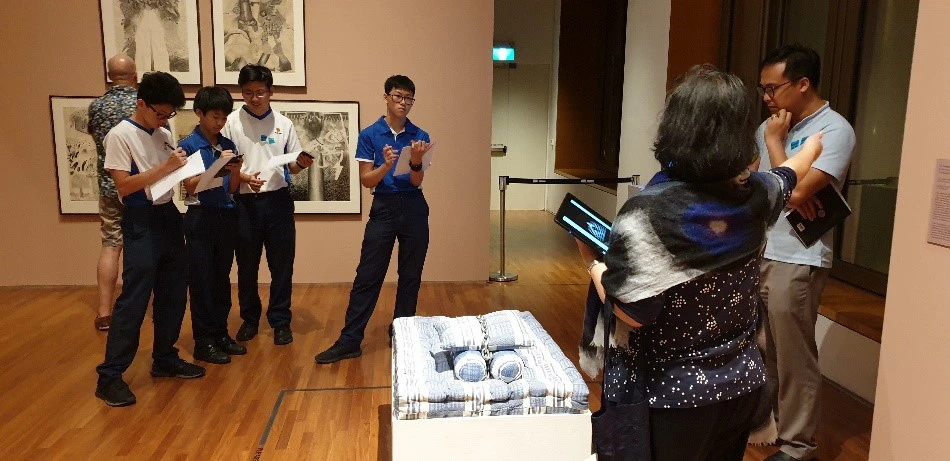

History students from Nan Chiau High School and River Valley High School had their curiosities piqued by Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960s–1990s. After a tour of the exhibition, students had a chat with curators Charmaine Toh and Seng Yu Jin over the messaging platform Telegram to answer their burning questions about the exhibition.

Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960s–1990s brings Asian histories to the fore by focussing on the complex relationships between art and society. In this edition of Ask A Curator, history students from Nan Chiau High School and River Valley High School visited the exhibition, and pitched their questions to curators Charmaine Toh and Seng Yu Jin over the messaging platform Telegram.

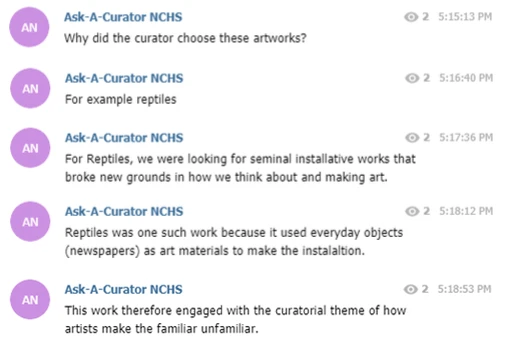

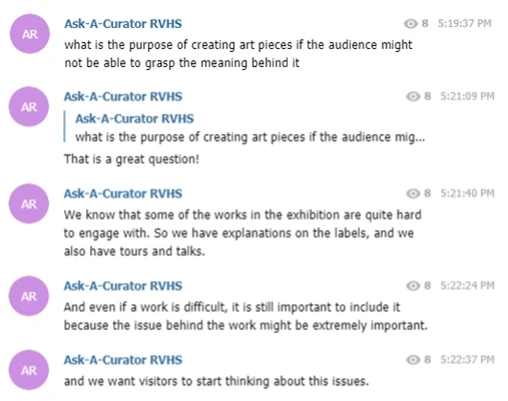

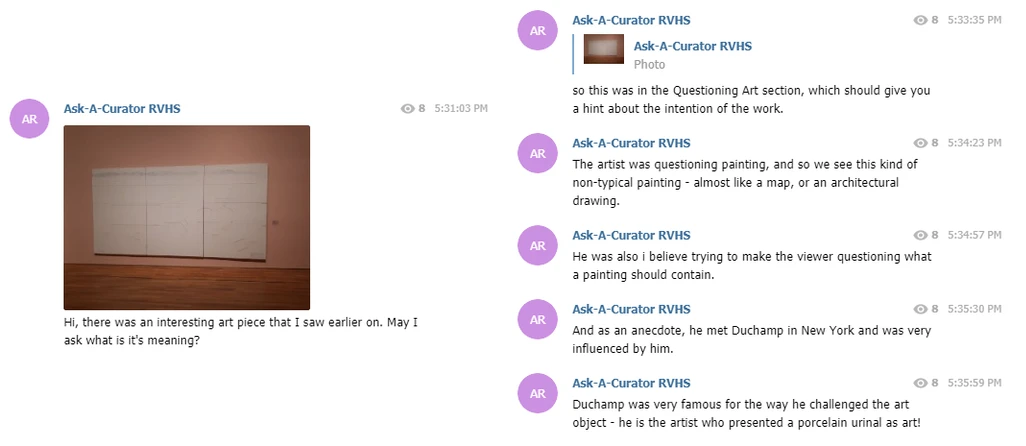

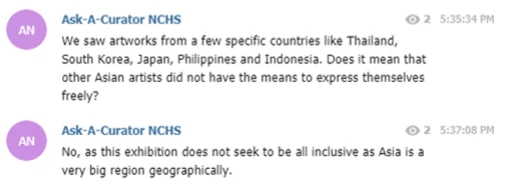

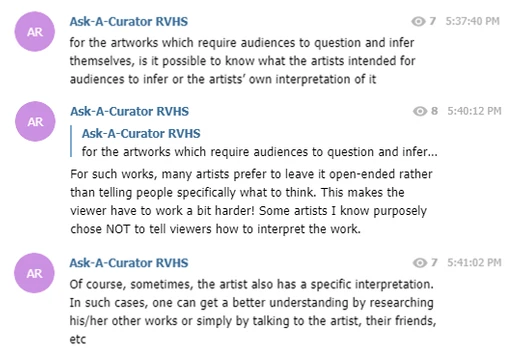

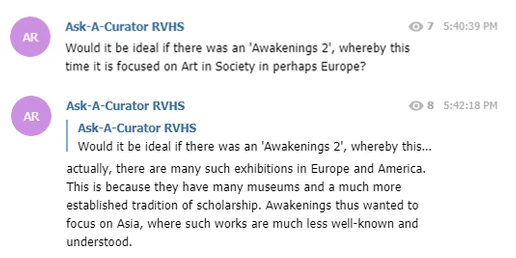

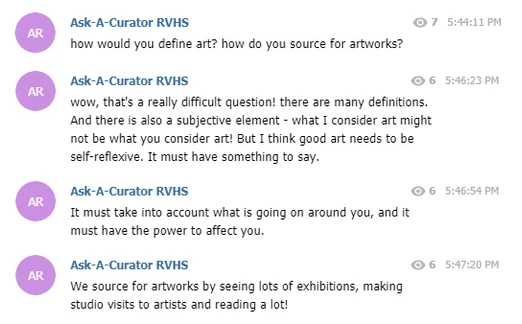

Students were encouraged to initiate frank discussion about the art on display and art itself. Parts of their conversations have been reproduced for this article. To read more, screenshots of their Telegram chatroom have been included in the image carousel below.

How did you decide the different topics to focus on in Awakenings?

Charmaine: We started out wanting to do an exhibition about the relationship between art and society. As we did our research, we gradually started seeing clearer connections between artworks, artists and cities, and we finally decided on key themes to feature in the exhibition.

What are some things you want visitors to come away with from the exhibition?

Yu Jin: The key message that we want visitors to take away is how art provides an avenue for us to question our assumptions and structures of power, and expose cultural hegemonies. The other key message is that we are as empowered as artists to affect change, and how Asian artists were making radical and experimental works, therefore not “belated” to the West.

Are there some works relevant to current social or political situations?

Charmaine: There are many pieces that, even though from the past, are still relevant today. For example, Tang Da Wu’s work They Poach the Rhino, Chop Off His Horn and Make This Drink about the poaching of rhinos – such animal protection issues are probably even more crucial now than ever before. Also, the work by United Artists’ Front of Thailand was created in support of democracy and Thailand is still debating such topics today.

I noticed many audio-visual works in the exhibition, is there a reason for this?

Charmaine: We did not specifically set out to include lots of videos, but the 80s and 90s was a period where artists gravitated toward video. This was a time when such technology became widely available and accessible, and artists responded accordingly. Media and advertising also started to occupy our imaginations – so artists used the same sort of language to communicate instead of “traditional” mediums like painting and sculpture. Naturally, they ended up being included in this exhibition.

There were some artworks on display that were first staged as street performances. These were presented as videos for this exhibition. Do you think the meaning of the original performance is lost if they are presented as videos?

Charmaine: This is a great question because art historians and curators have been debating this issue for many years! Of course, watching a live performance versus a video is a completely different experience. But many times, only the video (or photos) survives, so it is still the only way for future audiences to access the work. I don’t think the meaning is lost, but the experience is different.

Did people then understand what the artworks were meant to be, or how they were supposed to be interpreted? And how would you suggest one could form stronger interpretations of these works?

Yu Jin: Interpretations by the viewer have no right or wrong per se, only stronger or weaker interpretations based on how the work is analysed. Improving one’s interpretative skills requires an understanding of formal analysis (e.g. composition, colours, iconography), art historical knowledge (e.g. art movements and styles), and broader knowledge of culture, history and so on to contextualise artworks.

If there is one work that we must see, which would you recommend?

Yu Jin: I would say FX Harsono’s Pistol Crackers (at the end of the exhibition) as the work poses the question “What would you do if these pistol crackers were real?” This work is participatory as the viewer writes their answer in the book provided as part of the installation. It therefore provokes and empowers the viewer to be active in taking the first step to make changes, and awakens them to how they can think differently and question assumptions.

How do you define art?

Charmaine: That’s a really difficult question! There are many definitions. And there is also a subjective element – what I consider art might not be what you consider art! But I think good art needs to be self-reflexive. It must have something to say. It must take into account what is going on around you, and it must have the power to affect you.

Students interrogate their own assumptions by questioning art; learning, thinking and exploring art on their own terms. Questioning art is important to unlock the doors to knowledge, to develop appreciation for and understanding of art from multiple perspectives.

Editor's Note

If you're a student with questions or teacher wanting to get in touch for more related programmes, contact the Education team at shaun.soh@nationalgallery.sg.