“East is a Big Bird:” Retro-mapping Art, Representation, and Abstractions

In this article, Rachael Rakes (Artistic Director, 12th Seoulmedia City Biennale) explores maps and the different ideas of mapping. More specifically, the article presents different visual forms that perhaps serve as necessary parallels to maps, rather than serving as direct refusals or alterations. In doing so, Rakes outlines how maps capture the incongruence between indigenous (or non-Western) and Western perspectives on territory and the meaning of space.

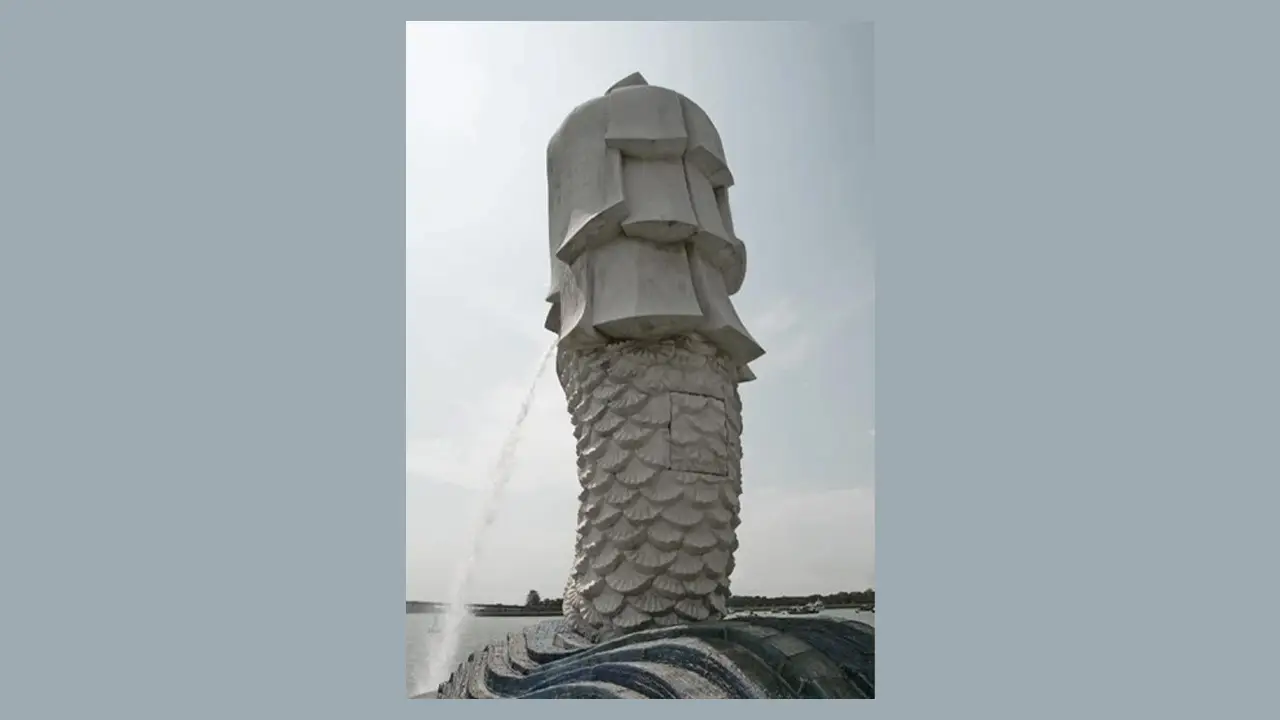

Unterbrochene Straßenmessung auf Singapore (Interrupted Road Surveying in Singapore)

c. 1865

Wood engraving on paper, 20.8 x 29.4 cm

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board, Singapore

In Nina Valerie Kolowrantik’s The Language of Secret Proof: Indigenous Truth and Representation (2019), the architect and researcher lays out the method by which she drafted community plans together with Puebla Native American communities. The plans were annotated and arranged in such a manner that make them informational enough to prove continued use by the Puebla community of land that the US government had claimed, but obscure enough to protect Puebla traditions and thus keep them sacred to the community. The final drawings produced are a mix of blueprint, abstraction and juridical documentation.

Kolowrantik elaborates on the approach:

“While Indigenous peoples’ ways of life, including farming, hunting and ceremonial practices on the land are accepted in court as proof of the existence of Aboriginal title, the formats of evidence that the US legal and judicial system considers reliable are mostly limited to empirical facts. Oral histories […] remain unheard, as they can’t be evaluated according to Western scientific standards.”1

These diagrams bridge those two ostensibly irreconcilable systems of knowledge—indigenous and Western—and serve as semi-obscured documentation nested within Western modes of enquiry. Beyond their necessity, they demonstrate what continually counts as visual representation in a specific and limiting regime of rational scientific thinking by employing coding and abstraction as ways of negotiating between Native ways of knowing and the structures that legislate them. While they are “maps,” they neither function as such for insiders or outsiders to the tribe.

The incongruence between indigenous (or non-Western) and Western perspectives on territory and the meaning of space has been studied for at least as long as coloniality has existed, but has been taken up in a more focused, reparatory way in the recent “post-” and “de-”colonial scholarship.The ongoing legacies of Western mapmaking define and coordinate not just land but also ecologies, community life, labour and time. In his book, Maps are Territories: Science is an Atlas (1994), scholar David Turnbull questions not just the rapid spread of Western cartography, but also examines why it was able to dominate so quickly. He writes, “Western maps are more powerful than aboriginal maps, because they enable forms of association that make possible the building of empires, and a concept of land ownership that can be subject to juridical processes.”2 This power is one bound up with hegemony–before the Western standard can be wielded such that it remains recursively dominant, it must first be established as definitive.

For the diagrams in Kolowrantik’s Secret Proof, line and shape are employed to deliberately obscure and preserve Puebla traditions. This is a deal brokered after centuries of erasing alternative knowledges, representations and identifications of the earth and its beings; it is a contemporary compromise to preserve or activate what little remains. The team behind the This Too, Is A Map for the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale (SMB12) has been conducting research alongside several artists and practitioners based on this present reality, examining traces, understanding the rules of representation and projecting visual communication strategies that amplify these forms.

Much has been written and proposed in recent years about the histories and uses of “alternative” or counter-maps, especially of Western-style maps that take more marginalized approaches by focusing on the underprivileged, non-human beings, less visible extractive or data-driven underground and overground systems, and so on. Artists and theorists have also long used Mercator style map subversions3—one of the most iconic being Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García’s’ America Invertida4 (1943)—to communicate the pervasiveness of the aesthetics of Western dominance and the violence of prevailing North-South perceptions. I’d like to move away from this milieu5 of artistic resistance into an introductory exploration of knowledge systems through different ideas of mapping, and consequently consider what these ideas indicate for foundations of form and abstraction, and how they might be used to modestly re-interpret or re-historicise these concepts in art and measurement systems.

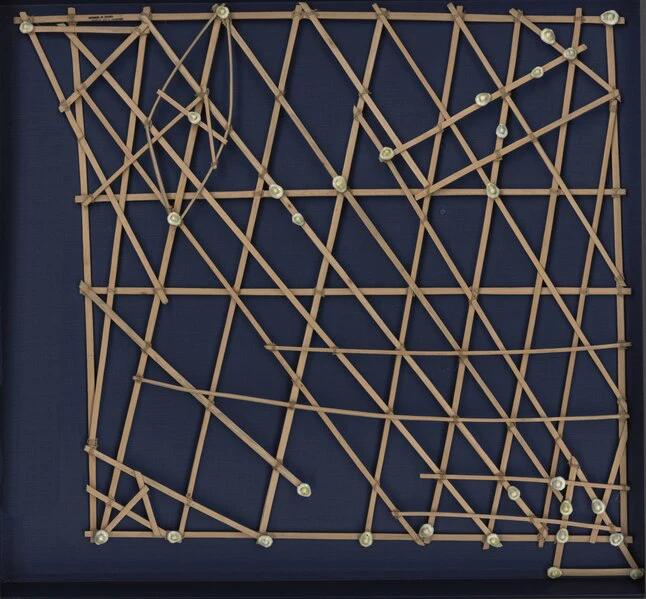

Polynesia faces the combined challenge of the climate change-induced physical erosion of its 1000 small islands and the ongoing degradation of ancestral traditions. Multiple causes contribute to the latter, ranging from the atoll bombings of the mid-20th century, industrialisation, tourism, pollution, and globialisation. The disappearance of land and cultural knowledge has resulted in the diminishment of the unique navigational knowledge employed by Polynesian fisherpeople, long-protected and passed down exclusively to only the most talented of navigators. Polynesian “stick maps,” or “shell maps,” are the traditional documents of wave patterns and ocean swells that navigators used for directing canoes to find food and move from island to island.

As is immediately evident from their form, these diagrams differ in many ways from what might be conjured when thinking of a map—almost any map. Specialised seafarers of the Islands used these charts made of bamboo sticks and cowrie shells, or “rebbelib,” to keep themselves on course during their travels between the islands, which are separated at times by hundreds of kilometers of open ocean. The sticks represent patterns of ocean swells, and the shells the locations of the islands. These patterns became embodied knowledge for navigators: information had to be memorised from diagrams, which was then combined with other knowledge, such as the “landmarks” for locations that a turtle would frequently appear at, other utterly mythical markers, as well as occasional constellational reference points. Memorisations mostly took place on land before the navigator went out to sea; the chart itself stayed on land, maintaining a position as something between an artifact and map. In anthropologist Thomas Gladwin’s ethnographic oddity of a book, East is a Big Bird: Navigation and Logic on Puluwat Atoll (1970), he records the levels of intended and innate concealment inherent to the process of this navigation, noting in one case, an example of an expedition ostensibly led by constellations during a night covered in clouds.4 This concealment extended not just to ethnographers attempting to glean insight, but to anyone outside of the navigational elite.

A recent article from the Smithsonian Institution, which has stick charts in its collection, refers to the maps as “less a literal representation(s) of an area and more of a guide to how waves and currents interact with islands.”5 The assumption about representation here marks a departure from an understanding so common in the West that it is be seen as a given. Despite the navigators’ near-perfect accuracy, representation is specific to every system of measure…... Historian Thonchai Winichakul writes about the cultural subjectivites of representation and accuracy in his book Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation (1994).6 Winichakul states that Western cartographers did not recognise the maps of ancient Thailand because they could not comprehend Thai ideas of space, which prioritised the spiritual realm as the primary index of existence. Winichakul writes, “The fact that the depictions of the earth are varied (for example, a square flat earth or a round one) does not indicate the development of local knowledge of the earth or lack of it. More probable, it suggests that the materiality of the human world can be imagined in more than one way, whereas the spiritual meaning of the world must be obeyed.”7 Space, in the Western sense, was simply not valued or respected in the same way—and this was a deliberate, systemic choice.

The “accuracy” of ancient Thai maps corresponds to the alternate accuracy of Polynesian maps, or even, for example, the scale size of rivers versus land as depicted by the great Joseon dynasty cartographer Kim Jeonghoor, who emphasised territorial shapes and waterways as key elements to life in his work. There are also the “upside down” maps of Han China and the maps of the Aztecs that co-prioritised important real and mythic birds, enlarging them to the size of whole cities. Or we can look to Australian Aboriginal maps—siblings to the stick charts in terms of their formalism—which prioritise “songlines,” or the paths of the ancestors, over latitudinal and longitudinal positions. Such relations of space to ancestry as story or cosmology have been noted in numerous pre-colonial global indigenous cultures. The Australian Aboriginal songlines are not merely ephemeral or superstitious: in addition to passing down traditional stories, they also laid out paths to food and water, recorded the historical memory of relations, and presented a ground and cosmic-level understanding of life dynamics. I want to use this example to return to the question of abstraction. Today, contemporary “abstract” paintings based on songlines from Aboriginal artists circulate at high value in art markets as quasi-abstract works. The inhabitation of realness, abstraction and the lost indexicality to other non-Western forms of the real6 make up a new kind of codex.

The paintings of Australian Aboriginal artists Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri are two such examples. Drawn from “maps” that are considered representative within their distinct knowledge systems, the paintings are traded as essential and non-representational—if culturally identifying—artworks. We have arrived at an interesting moment consequentially, in art history and the art market: paintings-as-objects interface with challenges to forms of mapping and data, not only because of the growing diasporas of people, plants and minerals, but also the resurgence and re-valorisation of non-Western knowledge. So, these “maps” inhabit multiple spaces of abstraction, formal magnetism, opaque forms of tracking and representation, and tokenised trade. They are, undoubtedly compelling, fascinating pieces in terms of what Western art history would consider “pure abstraction”, presenting an opportunity at the very least to rethink the qualifications of both sides of the representation/abstraction coin.

I’ll conclude this essay with a final example that may be familiar to readers: the recuperative mappings and subversions of artist Ho Tzu Nyen. In his installation work One or Several Tigers7, the artist employs several archival images that were part of or employed in the production of Singapore and Southeast Asia as territories. Within that work is the image Unterbrochene Straßenmessung auf Singapore (Interrupted Road Surveying in Singapore), a print produced in 1985 referring to an event that took place during a cartographic survey in 1835 conducted by George Drumgoole Coleman. The print depicts a tiger destroying the surveyors’ measuring tool, the theodolite. This print can be read as a moment of natural or spiritual revenge, or dissensus, with what’s happening over this land. The tiger living in tense but close commune with people and spirits of the land at that time serves as an occasional medium for the spirits and a meaningful force. Ho sees this event as a moment of rupture in the British survey mission. Such surveys were part of the colonial dream of imposing order in space, something, which cannot or should not be possible given that the space, in what would later be (erroneously) called Singapore, was not cosmologically measurable in such a way; spirits, animal, plant and human relations cannot be apprehended with such tools.8 Ho also points to this as the moment when extraction began, catalysed by the European demand for gambier and pepper—surveys, coordinated agriculture and nationalisation all came together to produce British Singapore, shaping it for a capitalist and Western presence.9 The separation created by the act of measurement is one of the most prominent forces in instating that wholesale change in the relationship between space and its inhabitants. The realms of the creative and mythically historic are sidelined. The abstraction of “land” via the act of scientific measurement becomes an irreparable violence, and the value generated by this specific kind of representation becomes its catalyst.

Through our research and collaboration with SMB12, we aim to present forms, shapes of data and cosmology as necessary parallels to maps, rather than focus on direct refusals or alterations. Most of the works on display do not resemble a map, and often appear more like abstractions rather than representations in the traditional art-historical sense. Instead, these works excavate knowledge foundations that might aim to pull together the traces of what bas been lost, presenting them alongside the systems of present infrastructural, surveillant and extractive cartographies, to find fellow stylistic motifs that lead to common understandings. We have additionally created, in the place of a show catalogue, an anthology that constellates research and ideas of mapping by considering multi-diasporic narratives and their entanglements with global industrial networks and revisionary mappings of infrastructures and cybernetics. This includes a new essay by our collaborators in this issue, Kathleen Ditzig and Anissa Rahadiningtyas, entitled “Countermapping Futurism: Bali and A Cybernetic Primitivism.” In a time of hyper-regimentation through the infrastructural mapping of mining, consumption, feelings, and tectonics, we are thinking about how to be realistic about the impossibility of repair while continuing to be realistic about the possibility of plurality. For all beings, diaspora life has become an index of its own, through both choice and coercion. What would it mean to speak and learn from that index first as our primarypoint of locality and departure?

In a subsequent essay in this series, SMB12 Associate Curator Sofia Dourron will discuss further inputs to this research alongside examples from the respective projects that resonate with these contributions. In a third contribution, we present a conversation with SMB12 artist Fyerool Dhama about his own conception of the aesthetics of pattern as politics, the mapping of retro-futurisms, and more.

With thanks to Yuvan Kumar for research support, and Amelia Groom for introducing the work fo Nina Valeria Kolowrantik.

Notes

- Nina Valerie Kolowrantik, “Secret Proof,” Prospections Journal: No Linear Fucking Time, https://www.bakonline.org/prospections/secret-proof/, accessed August 22, 2023.

- David Turnbull, Maps are Territories: Science is an Atlas, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press: 1994), 55.

- The Mercator map was first developed in the 16th century by Belgian Cartographer Geradus Mercator. It is distinguished by its consistent north-top orientation and an over-sized representation of the lands away from the equator, giving an implied dominance to the North and diminishing much of the tropical region.

- Thomas Gladwin, East is a Big Bird: Navigation and Logic on Puluwat Atoll, (Harvard University Press: 1970), 133-143

- How Sticks and Shell Charts Became a Sophisticated System for Navigation,” Smithsonian Magazine, 26 January, 2015, https://www.smithsonianmag.com, accessed 30 September, 2023.

- It’s worth mentioning that Siam Mapped was published contemporaneously to Turnbull’s and other landmark books from the 1990s on nationalism and Western supremacy, such as Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities and Edward Said’s Orientalism.

- Thongchai Winichaku, Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation, (University of Hawaii Press: 1994), 21.

- While this origin remains debated, many point to the origin of the name to Sang Nila Utama’s circa 15th century Malay Annals, where he identifies a large beast thought to be a lion in the region, and deemed it “Lion City” despite lions having never inhabited the place.

- Asia Hundreds and Ho Tzu Nyen, interview, “Mapping, Tigers and Theatricality: Narrating Fluid History through Media” https://asiawa.jpf.go.jp/en/culture/features/f-ah-tpam-ho-tzu-nyen/, accessed August 29, 2023