Performing Uninvited:

Tang Da Wu and Don’t Give Money to the Arts

Don’t Give Money to the Arts—the remains of Tang Da Wu’s seminal performance interventions in 1995—hangs in the DBS Singapore Gallery. Goh Wei Hao (Intern, Curatorial and Research) explores the historical and cultural contexts of these performances.

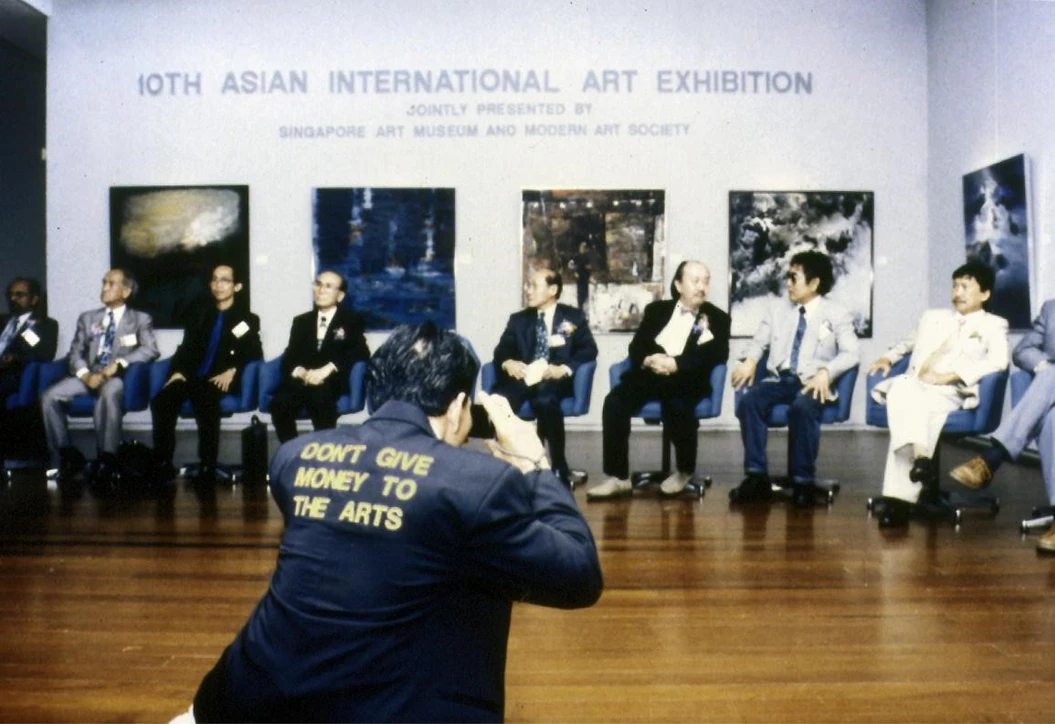

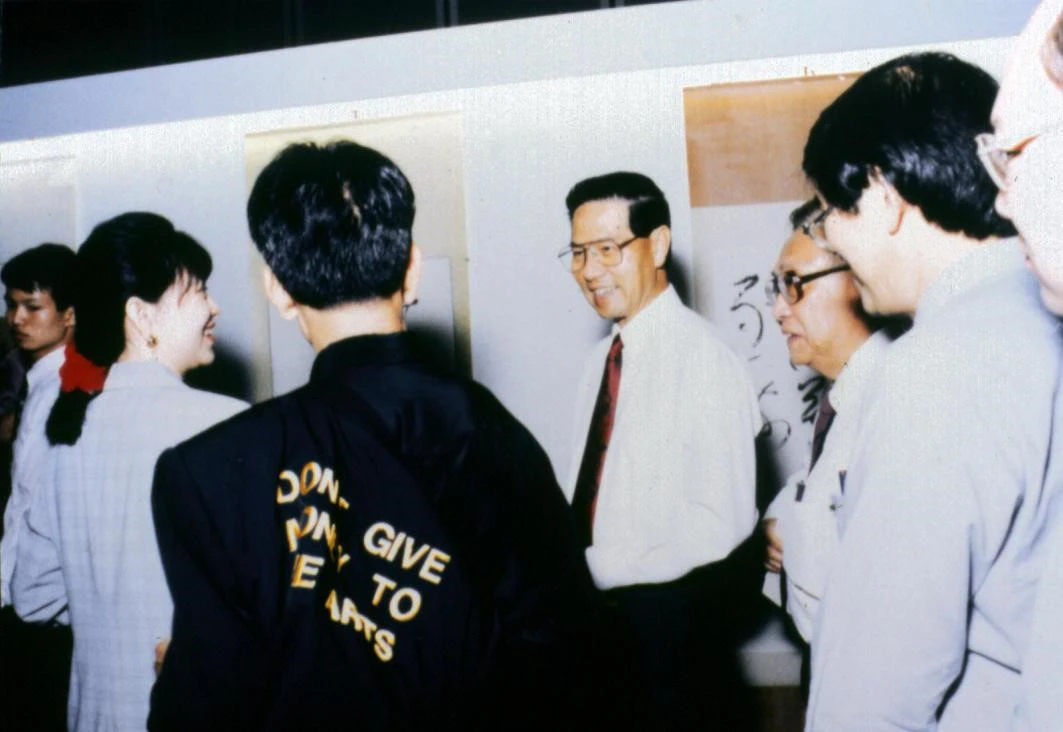

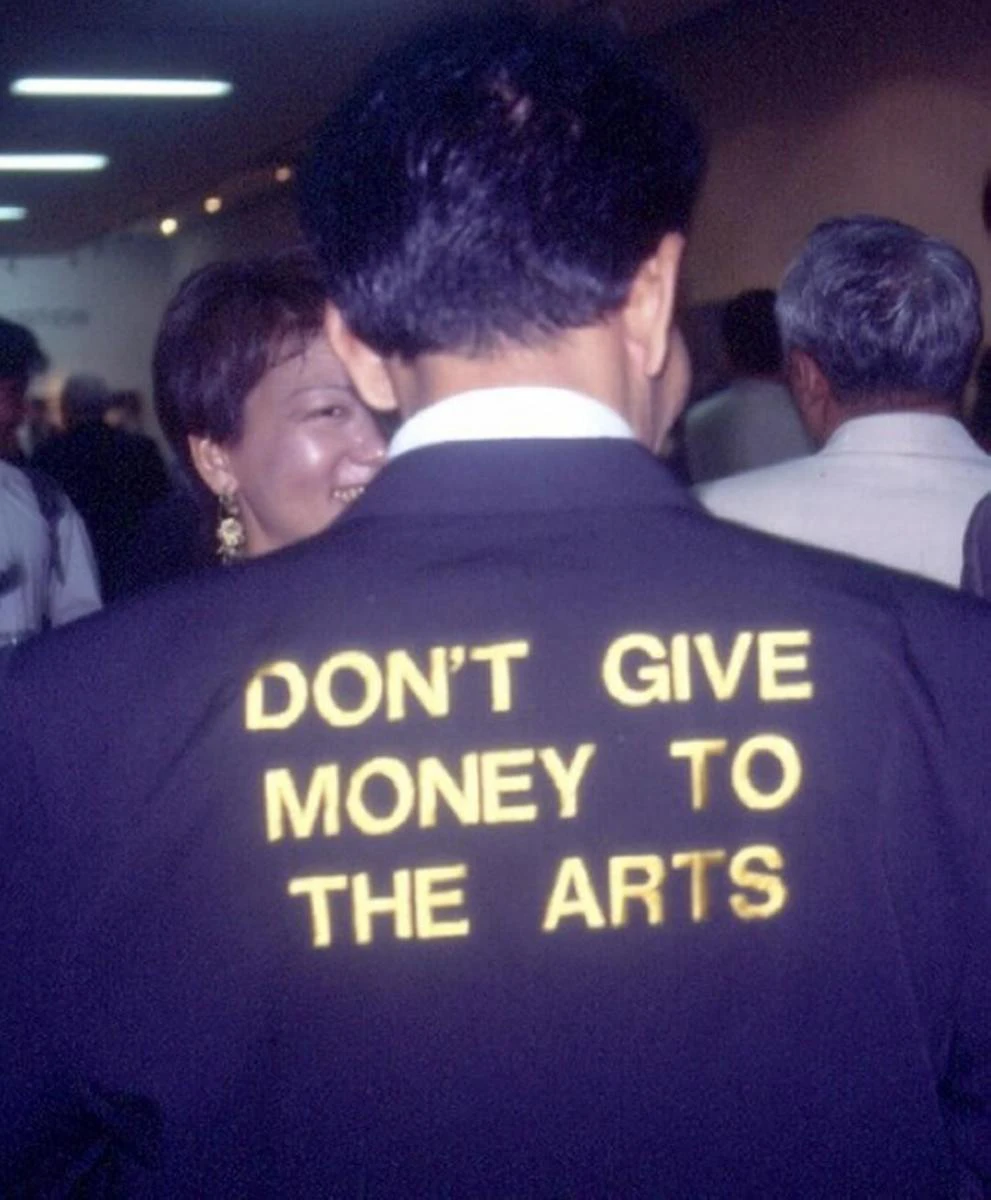

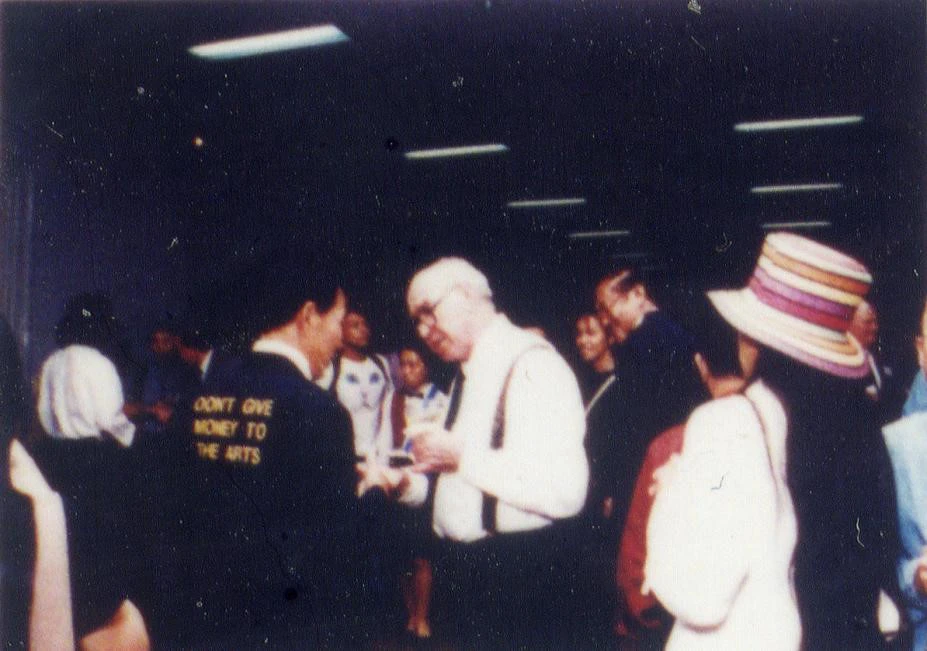

Don't Give Money to the Arts, 1995

Documentation of performance at the 10th Asian International Art Exhibition

Courtesy of Tang Da Wu,

photography by Chua Chye Teck.

In August 1995, the National Arts Council (NAC) and National Heritage Board (NHB) co-organised Singapore Art ’95 to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Singapore’s independence and the 50th anniversary of the United Nations. The biggest art event of the year was graced by guest-of-honour, then-President Ong Teng Cheong.1

Also in attendance was the artist Tang Da Wu, who approached the President and asked if he could put on his jacket with the words “Don’t Give Money to the Arts” embroidered on the back in gold.2 With the President’s consent, Tang proceeded to put on his jacket, before passing Ong a handwritten note with the words: “I am an artist. I am important.”3

Discussions of Tang’s performance have tended to focus on only three details: the jacket with its embroidered slogan, the handwritten note, and the encounter between the artist and head of state. What these past analyses ignore is the artist’s use of performance intervention, a mode of performance defined as intervening into a space to which the artist has no formal invitation. The aim of such transgressive and disruptive performances is to question the practices of the place that it is performed in.4

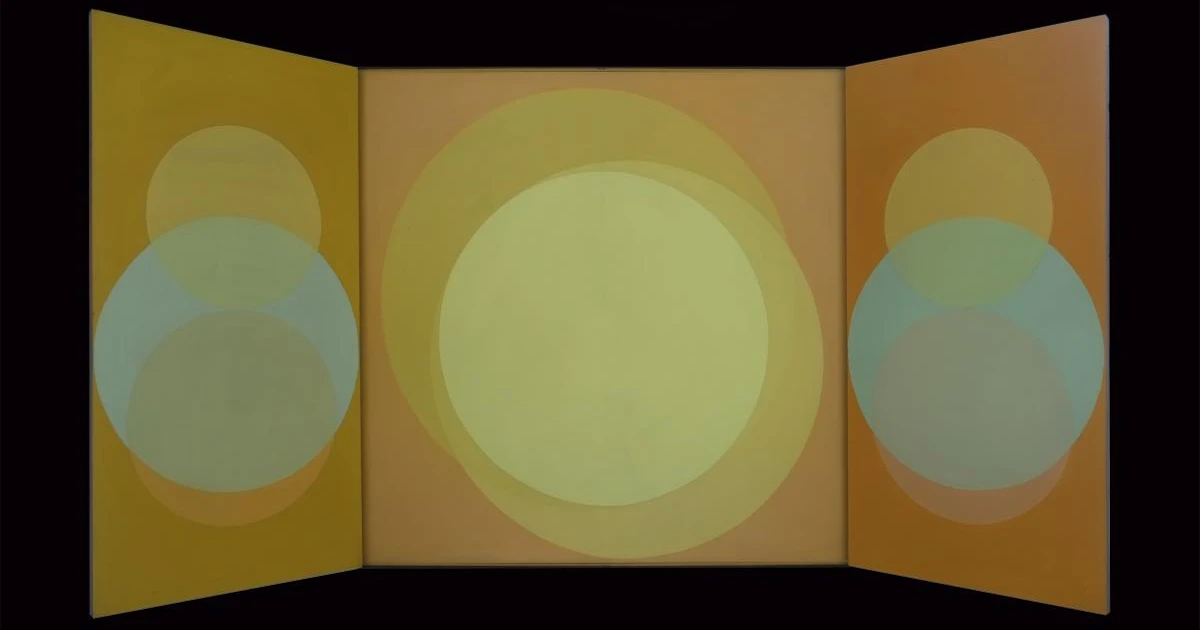

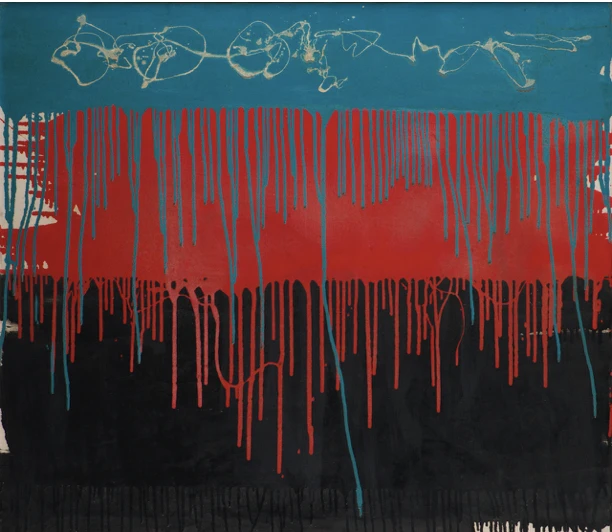

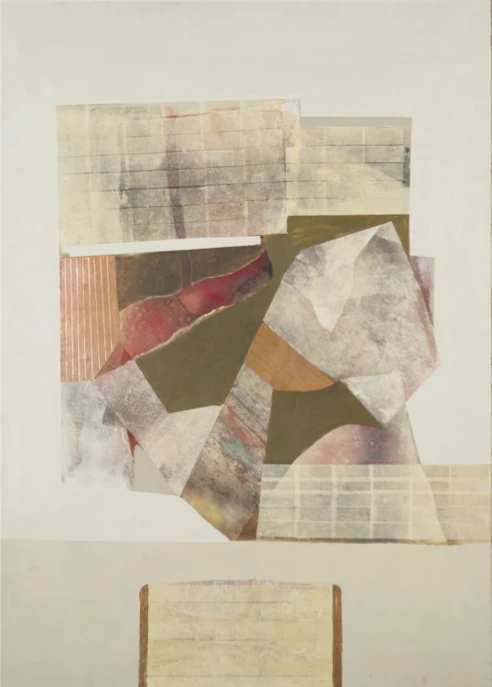

After the event, a reporter asked Tang about the intention behind his performance, to which the artist explained that he wanted to let the President know that public money was being used to fund “the wrong kind of art.”5 Tang never specified the art he meant; however as the artworks displayed at both events were predominantly modernist, abstract art, it is not difficult to hazard a guess. Modernism in visual arts is characterised by an experimentation with form and an emphasis on the medium, materials and process of the artwork. Stylistically, modernism in Singapore incorporated vernacular elements including local subjects such as shophouses, tropical fruits and the Singapore River. Modern artists believe that art “ought not to refer to anything other than itself”.6 Works by Ho Ho Ying, Wee Beng Chong and Thomas Yeo, members of the Modern Art Society who exhibited at the 10th Asian International Arts Exhibition, are part of the Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

In fact, Tang performed Don’t Give Money to the Arts twice. There has not been any writing on his first performance at the 10th Asian International Arts Exhibition (AIAE). The exhibition, which opened a week before Singapore Art ‘95, was co-organised by the Federation of Asian Artists (FAA), Singapore Art Museum (SAM) and the Modern Art Society (MAS) (Singapore).7 Performing the same intervention as he did for Singapore Art ’95, Tang went around the National Art Museum Gallery with his jacket, mingling with guests as fellow artist Chua Chye Teck followed closely behind to photograph these interactions.8

As a former member of the MAS, Tang would have been no stranger to those present at the Gallery that day. He had presumably left the Society as his practice differed from the abstraction that dominated the practice of MAS members.9 Although he went through several aesthetic phases over his decades-long career, certain key themes can be identified from his practice: advocacy for artists’ active participation in every stage of the artmaking process, the activation of the audience, and his concern for socio-political issues. These themes are best exemplified in Earthworks (1979), which deliberated the rapid urbanisation of the 1970s, and Tiger’s Whip (1991), which protested the hunting and consumption of tigers as an aphrodisiac.10

In the same interview after his second performance intervention with President Ong, Tang critiqued the “kind of art” that was being funded by the government as “too commercial” and said it had “no taste”.11 Both Singapore Art’ 95 and AIAE were co-organised and sponsored by the government through the NAC and NHB, but at the time of Tang’s performance, the NAC had ceased all public funding towards performance art – or more specifically, “script-less performances”.12

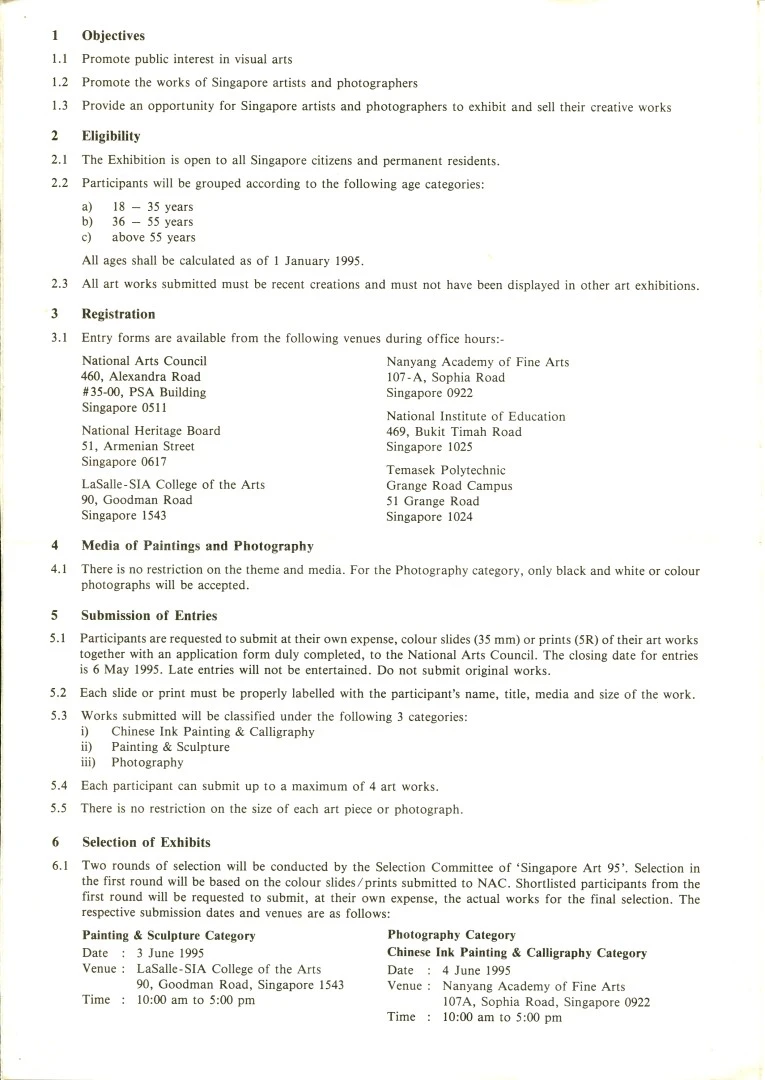

In addition to what is now commonly known as the “no-funding rule,” the government tightened the requirements needed obtain a Public Entertainment License (PEL), requiring applicants to submit a synopsis of the performance and a deposit.13 Even if Tang did apply for a license, it would arguably have been rejected due to the stigma surrounding performance art during that period as a result of Josef Ng’s 1994 public performance of Brother Cane, during which the artist snipped his pubic hair and stubbed out a cigarette on his arm. Many in the media, public and government questioned if his performance, and performance art in general, could be considered art. In the end, Ng was charged with committing an “obscene” act and banned from all public performances. From then on, the NAC withdrew funding for all “script-less” performances.14 According to the call-for-entries form for Singapore Art ‘95, only paintings, sculptures, photographs and Chinese calligraphy were accepted, effectively excluding performance art.15

Undeterred, Tang intervened in both exhibitions by performing at the openings. The artist managed to execute his performance as it was not immediately clear to the people present, including the organisers themselves, that Don’t Give Money to the Arts could be considered performance art. With the exception of being “live” and involving the artist’s body, despite its “no-funding rule” the government had no clear definition of performance art.16 Interestingly, Tang’s unwitting performance collaborators—the guests he greeted with his jacket on—were all part of the existing cultural milieu which privileged a certain artistic style over others. As Eugene Tan notes in his article on the work, “By implicating the [P]resident in a performance that had not been permitted, Tang demonstrated artists’ ingenuity in circumventing restrictions on artistic expression and highlighted the significance of art that could not be readily commoditised.”17 By performing in exhibitions that represented a rejection of performance art, Tang reclaimed these spaces, taking on the rules that withheld acknowledgement of his work. He transformed these restrictions into the aesthetic strategies that allowed his performance art to flourish.

Notes

- National Arts Council, Singapore Art ’95: 12-16 August 1995, (Singapore, 1995).

- Chua Chye Teck, interview by author, Singapore, December 26, 2019.

- The Straits Times, “Pay More Attention to the Arts – President,” August 12, 1995.

- Paula Serafini, "Prefiguring Performance: Participation and Transgression in Environmental Activism," Third Text 29, no. 3 (2015): 203.

- Low Sze Wee and Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, “Some Introductory Remarks,” in Siapa Nama Kamu? Art in Singapore Since the 19th Century, ed. Low Sze Wee (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2015), 21.

- The Straits Times, "Pay More Attention," 1995.

- Low and Mustafa, “Some Introductory Remarks,” in Siapa Nama Kamu?, 21.

- The Exhibition’s Singapore Organising Committee, 10th Asian International Art Exhibition: 4-31 August 1995, (Singapore, 1995).

- Chua, interview by author, 2019.

- Charmaine Toh, “Notes on Tang Da Wu’s Earth Work,” in Earth Work 1979, by Tang Da Wu (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2016).

- The Straits Times, “Pay More Attention,” 1995.

- The no-funding rule for unscripted performances which began in 1994 was only lifted in 2004; Clarissa Oon, “The National Arts Council,” in The State and the Arts in Singapore: Policies and Institutions, ed. Terence Chong (Singapore: World Scientific, 2018), 189.

- Ibid.

- Mayo Martin, “‘Brother Cane is a Part of Me’: Josef Ng Opens Up about Past Controversies and Future Hopes,” Channel NewsAsia, May 7, 2017, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/lifestyle/brother-cane-is-part-of-me-josef-ng-opens-up-about-past-8726810.

- A copy of the call-for-entries form was shown to the author by Koh Nguang How.

- Roselee Goldberg, Performance Art: From Futurism to Present (London: Thames and Hudson, 2013), 9.

- Eugene Tan, “Tang Da Wu’s Audacious Performance ‘Don’t Give Money to the Arts’,” Frieze 200, January 8, 2019, https://frieze.com/article/tang-da-wus-audacious-performance-dont-give-money-arts.