Yayoi Kusama’s Late Requiem for the Now

This essay, written to accompany the 2017 retrospective exhibition YAYOI KUSAMA: LIFE IS THE HEART OF A RAINBOW, considers the meaning of Kusama's art in today's world, as an artist who resists easy categorisation, balancing positions of self-obliteration and self-promotion.

Yayoi Kusama

2014.

Acrylic on canvas.

194 × 194 cm.

Collection of the artist.

Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore, Victoria Miro Gallery, London.

This essay was originally written to accompany the exhibition YAYOI KUSAMA: Life is the Heart of a Rainbow, 2017.

"My revolution of the Self, which has been such an essential part of my life so far, is all about discovering death. My destiny is to make art for my own requiem: art which gives meaning to death, tracing the beauty of colours and space in the silence of death’s footsteps and the ‘nothingness’ it promises." – Yayoi Kusama

“In the history of art late works are the catastrophes,” wrote the German critical philosopher Theodor Adorno when analysing the late musical style of the great Romantic composer Ludwig van Beethoven in his final years.1 To Adorno, these catastrophes do not indicate any decline in quality or a deleterious appraisal of the work of art in question. Rather, they are meant as a revelation of the productive and profound powers in innovative late works of art, whose disharmonies, dissociations and disjunctions point to a rejection of the extant order of things. They represent, as the cultural theorist Edward Said puts it, an “idea of surviving beyond what is acceptable and normal.”2 Catastrophe, or catastrophic thinking, could thus be one way to reconsider the wide-ranging oeuvre of Yayoi Kusama, who continues to put out work after work, and stage exhibition after exhibition, across the globe. One of the most recognisable names in art today, Kusama has become a tour de force brand and art industry superstar, whose life story and psychological hardship supply us with a gripping narrative to ground her expansive body of work. Yet if we prise the clichés and caricatures away, could a “catastrophic” reading of her intense prolific presence in the current art market bring us to a renewed understanding of what her art might mean for the world today?

Given the immense popularity of Kusama and the crowd-pleasing effects of her recent works and exhibitions, it is almost too easy to be cynically or despairingly dismissive of her success as an effect of the current art and lifestyle market. A more appreciative stance comes from the writer and curator Kevin McGarry, who called her recent collaboration with the high fashion house of Louis Vuitton a “fantastic symbiosis” that “triggered a re-evaluation of her impact in the light of the present.”3 Yet, it is sharply ironic that he now regards Kusama and her art as “atemporal,” despite crediting her as an artist who once responded incisively to her time:

"It emerged suddenly and has persisted without interruption or modification, apart from the expansive, continual evolution of its core components. Kusama hasn’t really changed with the times. The New York mid-century avant-garde and subsequent counter culture scene, where Kusama, the artist, was conceived, was the first and last time and place that her work would respond directly to. Her constancy has been a stable force that cultural and political epochs can be measured against. History can be witnessed in the changing of the world held in opposition to the continuity of Kusama."4

Unfortunately, such ways of complimenting the artist relegate her artistic production to a fetishised social viability locked within a particular period and place (1950s and 1960s America and Europe)5. Instead of constancy and continuity, Kusama’s vast production, right up to her latest My Eternal Soul series, needs to be considered as the artist arguing for the possibility of alternatives, variations and elaborations. As Adorno points out, late works by significant artists are often untimely (rather than atemporal) and part of a process of irascible subjectivity which produces an overabundance of material that cannot be reduced to a method or system, and allows them to step out of their time frames.6 And as Said might have, I see Kusama’s “artistic lateness not as harmony and resolution but as intransigence, difficulty, and unresolved contradiction.”7

Done mostly in the past decade, Kusama’s two large-scale series Love Forever (2004–2007) and My Eternal Soul (2009–ongoing) emerged quite unexpectedly and diverged from her more usual motifs of dots, nets, plants and phalluses. Comprising 50 white-based canvases replete with chains of motifs such as eyes, dolls, gadgets, flowers, saw blades as well as profiles of female faces, the images in Love Forever were initially completed with a black felt marker, a quick-drying and thus spontaneous medium that did not allow for any revisions but allowed Kusama to showcase her tremendous dexterity and drawing skills.8

The monochromatic schema of the series belies a change of attitude, one which reached towards a freer spirit of humour and optimism. The title of the series is a phrase which was written on round cards that she handed out at her 1966 solo exhibition at Castellane Gallery in New York, Peep Show/Endless Love Show. Here, a torrent of happy images overflows from her canvases and upbeat words like “spring,” “morning,” “youth,” “flower,” “star,” “universe” and “love” surface repeatedly in the canvases’ individual titles.9

As the curator Masahiro Yasugi suggests, “Kusama shifted from an introverted, gloomy mental state to an affirmation of her own existence and a sense of emancipation in regard to the outside world.”10 But the scholar Akira Tatehata also notes that even with these new pastoral sentiments, the pictures remain undergirded by a strong desire for repetition and proliferation, an obsessive quality rooted in the fear of emptiness (rarely does she leave voids in her images) and which counteracts the upbeat fecundity implied in her imagery.11

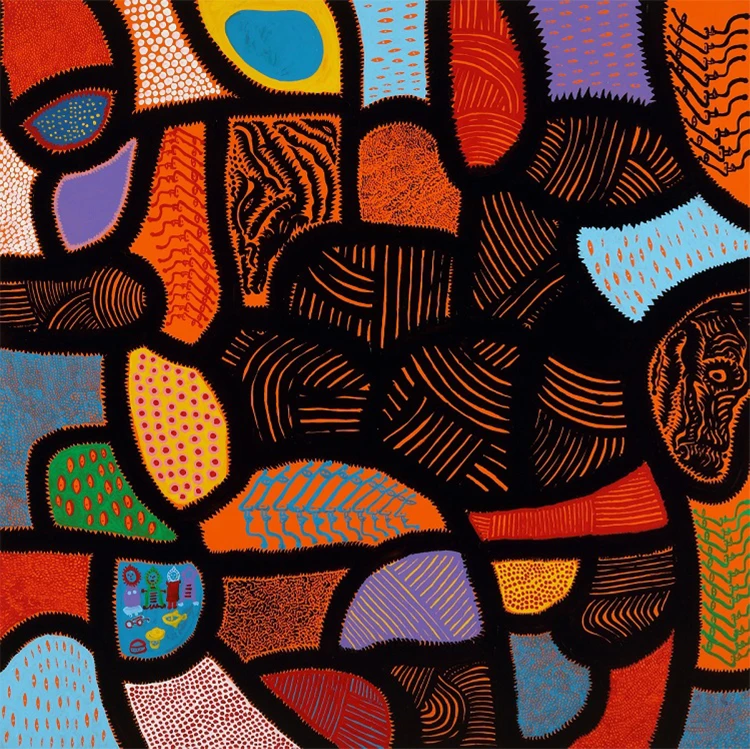

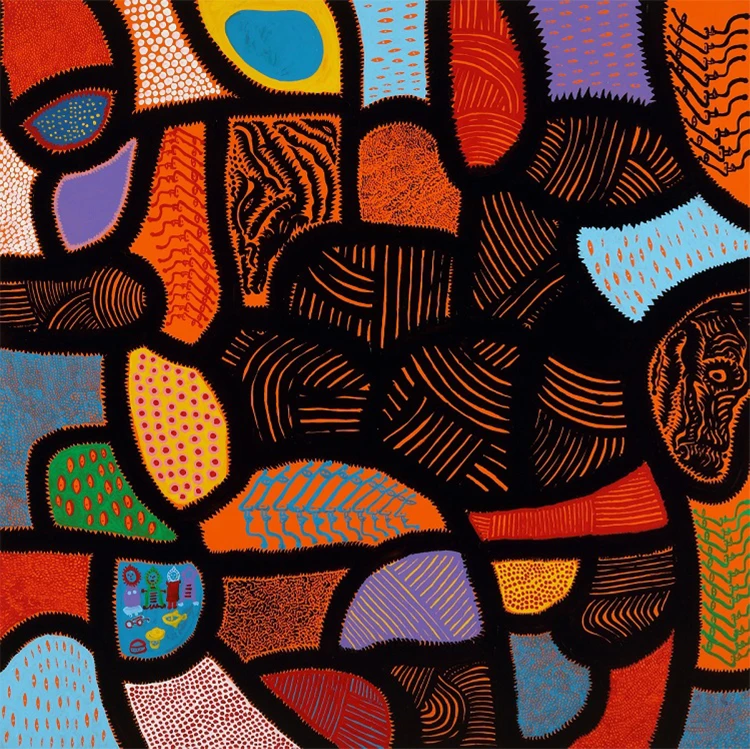

Kusama’s ongoing series My Eternal Soul presents an extension of this outwardly friendly face but her canvases now integrate both drawing and painting techniques, and a riot of brilliant colours from acid and electric hues to metallic shades of copper and silver. They are filled with an abundance of decorative, iconographic and biomorphic elements never before encountered in her previous works, alongside older motifs from the 1950s.

This fresh departure has made scholars like Tatehata both perplexed and excited, with each wanting to reach an explanatory framework for these brave new works:

"While it may be an exaggeration to state that My Eternal Soul breaks down the all-over composition that Kusama has maintained in her paintings thus far, it is also evident that she is no longer attempting to control space in a uniform manner. She sometimes expands her signature polka dots so they become coloured surfaces with roughly rounded edges; it addition to representational images, such as the profile of a human face, organic shapes that appear to be amoebae or other small organisms float against the grounds of the paintings. Thus the grounds have transformed from repetitive geometric patterns to “homages to life” that provide the compositions with teeming narrative."12

More remarkable is how Kusama herself executes her canvases. Initially wanting to complete only 100 paintings, she found herself unable to stop (they now number over 500) and her canvases have become progressively larger, evolving from the F100 (130.3 x 162 cm) used in Love Forever to the S120 (194 x 194 cm) that now dominates. Similar to Love Forever, the canvases are not worked on vertically as per easel painting, but positioned horizontally on her table and painted on from all directions, either by rotating the canvas or moving her own body. It has been mentioned that many of the canvases in My Eternal Soul possess an omnidirectional structure, and understandably so as their final orientation is only decided by Kusama after the paintings are completed.13 Whilst critics have tried in their formal analyses of concrete and abstract images to distinguish the transformations inherent in the paintings of My Eternal Soul from those in Love Forever and past paintings, the more enduring sense conveyed is that of Kusama’s surprising ingenuity, that “the works reveal a certain repetition of imagery until Kusama suddenly takes a completely different tact, suggesting a production process in which she faces the canvas without any conscious plan and spontaneously creates a painting.”14 Yasugi concedes that her recent or late paintings “in no way represent a final destination” even when one looks back at the past decade of her career:

"To many people, by 2004, Kusama’s art had already seemed to have peaked, no one could have imagined that a work like Love Forever was just around the corner, or that having finished that phase in her activities, a holistic compilation of every aspect of her work would subsequently emerge. All expectations were once again defied in a spectacular way with the emergence of My Eternal Soul."15

But what might such defiance suggest for audiences who are seduced by the bright and aestheticised surfaces of the My Eternal Soul paintings? Or put off by Kusama’s seeming complicity with the art market, with the profuse production of wall-friendly paintings and sleek infinity mirror rooms that speak to today’s screen-saturated era of entertainment, and in contrast to her earlier counter-culture activities of the late 1950s to 1970s? Scholars and curators have tended to speak more redeemingly about her earlier practice in America and Europe.

Yuko Hasegawa sees Kusama’s art and its reception as indexical of the negative but increasingly prevalent social and psychological realities (she speaks about schizoid otaku cultures of extreme obsession and acute social withdrawal) that arise from an electronically and information-driven society. But she harks yet again to Kusama’s work of the 1960s, and the putative utopianism of that period which is seen as a more incisive counterpoint and answer to overcoming today’s ills (with Kusama overcoming hers through art practice).16 Similarly, the art historian Jo Applin also positions Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field from 1965 as the most critically successful version of her mirror rooms. Kusama’s more recent “dazzling” room installations, such as Fireflies on the Water (2000) offer “a more joyful—because fantastical—experience, something her earlier installations such as Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field never quite achieved,” but this spectacularity is achieved at the cost of the “more complicated dialectical position upon which the earlier rooms necessarily rely.”17

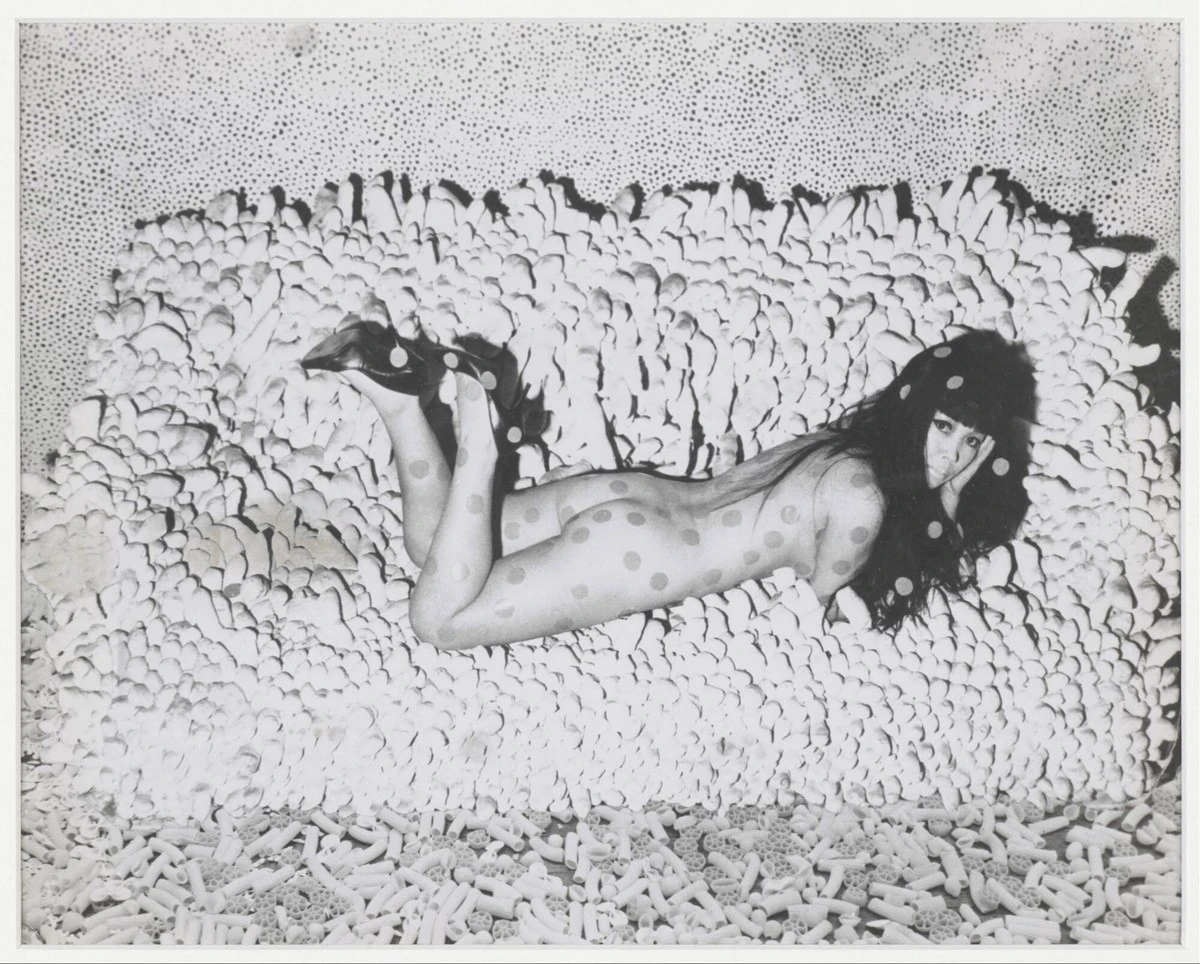

It is perhaps counterproductive to champion one phase of Kusama’s art over the others given that she is also still making artworks, but also in light of her defiance against categorisation in the 1960s art world. In 1961, she announced her own ambitions by unveiling a monumental painting (the size of a 33-foot wall), rivalling the works of other male American abstractionists but at the same time posed nude on her phallus-studded couch Accumulation No. 2, which itself critiqued phallocentrism by compounding it, parodying and then de-differentiating the phallic symbol through compulsive repetition.18 Rather than isolating one part from the other, it is infinitely more productive to mine the gaps between the parts—the relationships between people, society and nature—revelling in the psychological and physical frictions that Kusama sees between human beings, the accumulation of which forges her work.19 Kusama’s late works are not divorced from her early oeuvre, and one way to understand their connections and fissures would be to read them against one another. Paradoxically, this is most efficiently done in her large exhibition surveys and retrospectives, where the range and depth of her practice can be demonstrated and produce other fractious conclusions.

It can thus be said that Kusama confounds our expectations with contradictions—her calls to universal harmony and humanitarianism are continually undercut by words and actions that seem to head in the opposite direction, thereby confounding our understanding and stalling our acceptance. And she has never been coy about holding these different energies together even till today. The viral and proliferative branding strategies––now used to great effect by multinational companies like Kusama’s recent collaborative partner Louis Vuitton – and the production of instantly recognisable symbols or monograms have not been alien to Kusama (who has consciously deployed these tactics since the 1960s, even talking proprietarily about polka dots as the trademarks of her Kusama Happenings). In the late 1960s, she founded a slew of commercial and professional ventures—Kusama Enterprises, Kusama Polka-Dot Church, Kusama Musical Productions, Kusama Fashion Company, Kusama International Film Production and the Body Paint Studio. Each of these had their discrete function, but they also worked together as a whole, aiding the impact of adjacent counterparts. Her film company documented her Happenings, which would then be sent to television stations to be broadcast; her fashion business provided costumes (with scandalous cut-out holes to showcase the body) for her performances and fashion shows, some of which were sold at major department stores in New York. She was also keenly aware of the need to document and be documented (this brings to mind the importance of Hans Namuth’s iconic photos documenting Jackson Pollock dripping paint all over his floor bound canvas in cementing Pollock’s artistic impact). Hiring photographers to capture her works and herself posing with them, she also courted the media whose press reports, which sensationalised her life and art and made her famous.

Her presentation of 1,500 mass-produced reflective silver balls on the grounds of the 1966 Venice Biennale was one of her boldest acts. This performative installation was entitled Narcissus Garden. She was not officially invited to be an exhibiting artist but had received permission from the committee chairman to use the lawn outside the Italian Pavilion (and the financial assistance of Italian artist Lucio Fontana to fabricate the work). What eventually caused a scandal was her daring during the opening week to sell the mirror balls for two dollars each to passers-by (her advertisement placard stated “YOUR NARCISSIUM [sic] FOR SALE”), together with flyers printed with British critic Herbert Read’s praise of her work.20 She was eventually stopped for unauthorised hawking of commodities (although the work remained) but not before capturing the attention of the international press, becoming the art world outsider who deigned to uncover, and even protest, the economic system and commercial transactions embedded in the production, exhibition and circulation of art, whilst at the same time benefitting from the added attention showered upon her practice. The icing on the cake came finally in 1993 when she was invited back to Venice to represent Japan as the first artist to be granted a solo presentation in the Japanese Pavilion. Narcissus Garden has since become a high-value work that has been reconstructed for a multitude of international museum exhibitions but without its original orientation as a participative performance with the artist and visitor.21

It is therefore not entirely clear who is co-opting whom: Kusama is a figure who enigmatically challenges our understanding at every turn with her equal but countering positions of self-obliteration or enclosure, and self-promotion or exposure. She is on the one hand hermetic and obdurate, yet on the other driven to exhibit her work everywhere and be completely open to the public and to the future. It would be wrong to regard Kusama today as a benign purveyor of delight: the charming and disarming ways in which she uses and outsizes motifs such as animals, vegetables and flowers, do not diminish the seriousness and the somewhat ambiguous radicalism of her intent. After all, in the 1960s era of Flower Power, floral spectacles were extolled as virtuous forms of non-violent resistance to the Vietnam War. As someone who has witnessed the major geopolitical conflicts of the twentieth century, Kusama is in the twenty-first (digital) century an adroit operator who already exploits the slippage between the art and the entertainment industry, where visual material and information data flow together in computing streams to various audiences, and ideas, songs and speeches can be repackaged into business proposals.

I want to return once more to the question of Kusama’s relevance in today’s Trump and Twitter times, a period of growing religious, rightist or even fascistic rhetoric; of media opportunists who peddle soundbites and “alternative facts.” In a book aptly and presciently titled, Amusing Ourselves to Death, the American cultural critic and educator Neil Postman has accurately diagnosed our current plight: that we had mistakenly feared the restrictive, censorious and emaciating powers of the state as depicted in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four but did not seriously contend with its obverse picture in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, where society is sedated by technology and engorged by instant-gratification consumerism. Postman sums it up in his Foreword:

"What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy."22

Postman’s description and warning of a Huxleyan trivial television and social media culture fits largely with the popular, if misguided, reception of Kusama’s early and late works. Kusama herself has projected an ugly disaster scenario for human society and the planet.23 But if Postman seeks to foreclose the death of human sanity and sentience (that people “did not know what they were laughing about and why they had stopped thinking”) through political education,24 Kusama seeks death itself, placing it at the centre of her artistic being, having spent a lifetime chased by the nightmare of her own obliteration by her hallucinations. Yet this fixation on death is what propels her “to make art that will last forever,” to live beyond 500 years, pitting her meaningful cosmic eternity against the abject, temporary culture of today’s world. Against her 24 brightly cheery My Eternal Soul canvases (2014–2017) displayed in this exhibition, darkly worded epithets in their individual titles such as “THE URGE TO DIE COMES ON A DAILY BASIS. HOPING THAT YOU COME ACROSS MY DEATH” contrast starkly with others that are brimming with “LOVE,” “LIFE” and “PEACE.” “Without illusory hope or manufactured resignation,” Kusama can thus be considered a figure of lateness alongside Adorno and Beethoven, “an untimely, scandalous, even catastrophic commentator on the present.”25 And as Said surmises, “late style does not admit the definitive cadences of death; instead, death appears in a refracted mode, as irony.”26

Installation Views

Notes

- Theodor W. Adorno, “Late Style in Beethoven,” in Essays on Music, ed. Richard Leppert, trans. Susan H Gillespie, (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2002), 567.

- Edward W. Said, On Late Style: Music and Literature against the Grain (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006), 13.

- Kevin McGarry, “Epilogue,” in Yayoi Kusama, ed. Louise Neri (New York: Rizzoli International, 2012), 255.

- Ibid.

- Kusama's mature career can be broken down into three distinct phases: her time spent in New York in the 1950s and 1960s; a period spent mostly in Japan from the mid-1970s until the 1980s; and her return to international attention from the late-1990s onwards. There is more critical literature devoted to her Euro-American phase than her subsequent two phases.

- Adorno, op. cit., 566–567.

- Said, op. cit., 7.

- Akira Tatehata notes that the style first appeared at the KUSAMATRIX exhibition at Mori Art Museum in 2004 where she drew profiles of herself directly onto the museum walls with marker pens. See Akira Tatehata, “Everyone’s Avant-gardist,” in YAYOI KUSAMA: Eternity of Eternal Eternity, exh. cat., eds. Masahiro Yasugi, et al. (Tokyo: The Asahi Shimbun, 2012), 16.

- Masahiro Yasugi, YAYOI KUSAMA: Eternity of Eternal Eternity, exhibition catalogue (Tokyo: The Asahi Shimbun, 2012), 25. Since the late 1990s, Yayoi Kusama has been the subject of a remarkable re-evaluation. This process began with a solo exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1998 that, under the title Love Forever, focused on the time Kusama spent in New York City between 1958 and 1968.

- Ibid., 144.

- Tatehata, op. cit., 17. This sentiment is borne out once more when the mirrored peep box Infinity Mirrored Room – Love Forever, first made in 1966 for Kusama’s Peep Show/Endless Love Show and subsequently remade in 1994, is later in 2008 displayed together with and surrounded by the entire series of Love Forever canvases, reflecting all around the wall hung pictures of the series. The installation features a box with peepholes that uses facing mirrors and flashing coloured light bulbs to produce infinite reflections. Yuko Hasegawa argues that peep boxes are more than a simple optical device “because they embody Kusama’s monomaniac fears––fears that compel her to continue weaving surfaces in order to confirm her own existence” and expose our underlying anxiety about the uncertainty between the internal and the external. See Yuko Hasegawa, “The Spell to Re-integrate the Self: Yayoi Kusama,” in Afterall 13 (2006), https://www.afterall.org/journal/issue.13/spell.re.integrate.self.significance.yayoi.kusamas (accessed 20 March 2017).

- Akira Tatehata, “New Paintings,” in Yayoi Kusama, ed. Louise Neri (New York: Rizzoli International, 2012), 240. Despite the admiration of the ostensible breakthrough, Tatehata finds himself unable to shake off what he knows of Kusama: the new works are humorous but also eerie and estranging, containing “paradoxical elements of obsessive oppression and emotional salvation” that he sees as consistent with her oeuvre.

- Yasugi, op. cit., 144.

- Ibid., 145.

- Ibid., 146.

- Hasegawa, op. cit.

- Jo Applin, Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirror Room - Phalli's Field (London: Afterall Books, 2012), 80.

- Mignon Nixon, “Posing the Phallus,” in October 92 (2000) 112–4.

- To sell the artwork in the price range of food in the supermarket or handkerchiefs and socks. Based on the idea of equal access to all, the price should be as low as possible to meet the lifestyles of ordinary people.

- Lightweight and can be moved freely. Anyone can have a new experimental garden of their own design in their own garden and the idea of landscaping is contradicted.

- Despite this about-face, Narcissus Garden can still be regarded as a cautionary tale against the excessive visual self-love encouraged by photographic selfies of the Internet and social media age, if one recalls the myth of Narcissus who became tragically transfixed by his own watery reflection.

- Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, (London: Penguin Books, 2006), xix.

- Kusama, Infinity Net, op. cit., 229. Kusama writes in her final entry titled “To Make Art that Will Last Forever”: “The arrogance of human beings, who have progressed so far through science and the mastery of machinery, has caused them to lose touch with the radiance of life and led to the impoverishment of the imagination. The increasingly violent information society, the homogenisation of cultures, the pollution of nature––in this hellish world, the mystery of life has ceased to breathe. The death that awaits us has lost its sublime quietude and we have abandoned our claim to a peaceful end.” hello

- Postman, op. cit., 163.

- Said, op. cit., 14, 24.

- Ibid., 24.