Tatreez Illuminations: GLISTEN in Palestinian Embroidery & Dress History

Wafa Ghnaim explores the resonances between Lisa Reihana's GLISTEN (2024) and motifs found in traditional Palestinian embroidery, also known as tatreez.

Lisa Reihana (Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Hine, Ngāi Tūteauru, Ngāi Tūpoto). GLISTEN. 2024. Steel frames, shimmer discs and a wind chime, dimensions variable. © the artist. Commissioned by National Gallery Singapore.

When I first encountered GLISTEN in September 2024, I was mesmerised by the resplendent triangular installation, a spectacle of shifting brilliance against the backdrop of the city. The luminous designs constructed with 114,000 reflective square discs chequered across each side of the sculpture and enlivened by the sunlight, peacefully scintillated in the breeze, speaking their own language through sound, movement and light.1 The sound of shimmering medallions moving with the wind intertwined with the sounds of wind chimes hanging nearby, softening the sounds of the city. The voices and footsteps of other visitors also faded, completely drowned out by GLISTEN’s symphony of sound and stillness, instilling a much-needed meditative space to reflect, wonder and listen. As a Palestinian, I had spent the last year watching the loss, destruction and tragedy that had unfolded in Gaza on my phone screen with great uncertainty and sadness.2 But when I approached GLISTEN, I was captivated by the work of Aotearoa New Zealand artist Lisa Reihana, in particular because of the electric red, yellow and gold geometric patterns reminiscent of motifs found in traditional Palestinian embroidery, or tatreez.3

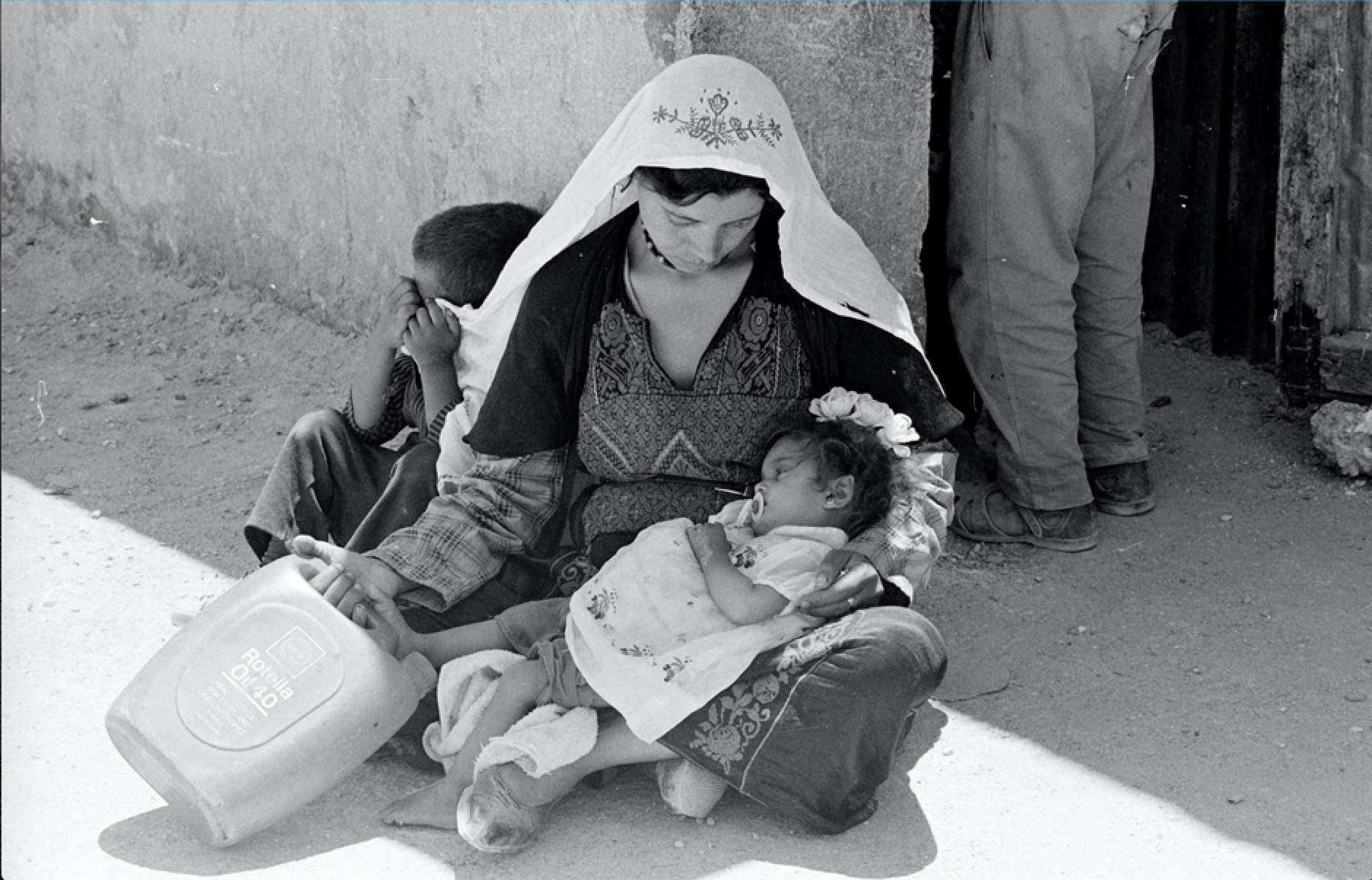

In 2021, UNESCO inscribed the art of embroidery in Palestine—including its practices, skills, knowledge and rituals—on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.4 This recognition highlighted the cultural significance of embroidered traditional Palestinian garments, particularly the thobe, which incorporates intricately stitched iconographies such as birds, trees and flowers.5 Through needle and thread, Palestinian women have illustrated their lives with vibrant stitches, patterns and fabrics, creating stunning dresses that reflect their heritage. Traditionally, young Palestinian girls learned tatreez from their mothers and grandmothers through storytelling and study, passed down generations maternally through oral transmission. In the same spirit, my sisters and I began learning tatreez from our mother, Feryal Abbasi-Ghnaim, who wielded needle and thread as pen and ink—a visual language that told the stories of our lives.6

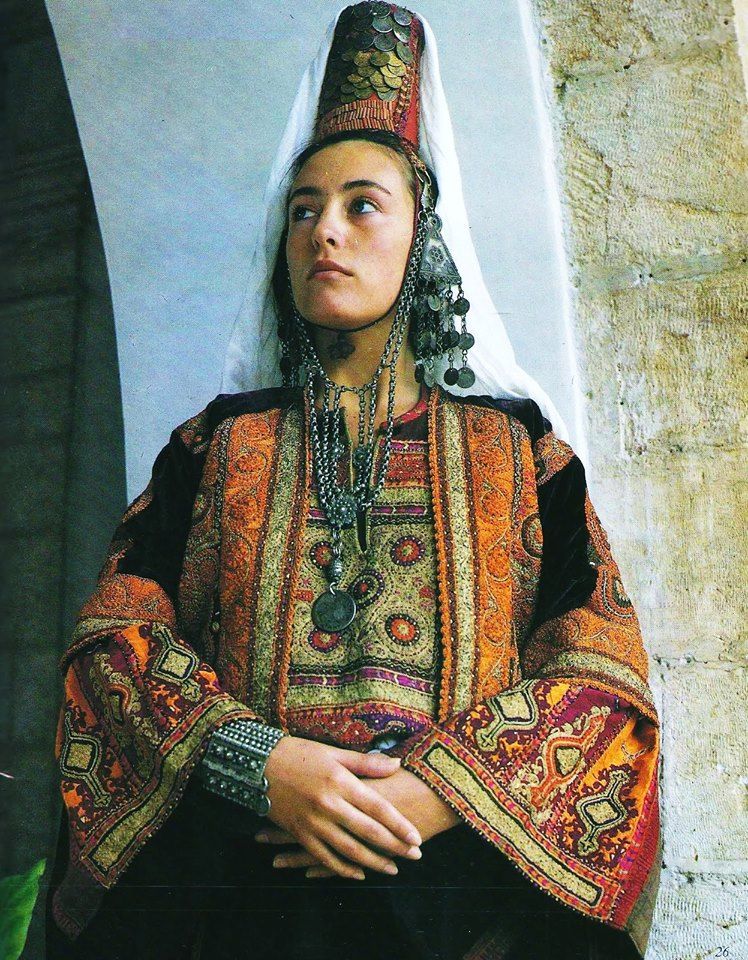

For centuries, the thobe has recorded an “individual or a place: a wife, a mother, a daughter, a family, a house, a village, a town, a field, a market.”7 During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Palestinian women adorned themselves with rich ensembles that expressed their connection to the land—first through their specific regional (city, village, tribe) identity, and then through their societal associations (townsperson, villager, nomad). Over time, Palestinian identity, beauty and fashion were understood through an Orientalist lens, shaped by “Holy Land” tourism in which Americans and Europeans sought evidence of their own Christian heritage in Palestine through its material culture, which they perceived as remnants of the biblical past.8 However, the widespread European and American belief that dress in historic Palestine was unchanging, stagnant and static since biblical times—only modernised with the advent of European influence—is an oversimplification, and ultimately incorrect.

While the fashion of Palestine can be traced over centuries, it is a constantly evolving phenomenon, far more diverse than assumed.9 Although Palestinian women and men dressed according to regional and societal affiliations, women’s styles varied even within the same village or region at any given time. Some styles were common across multiple regions, while others were shared throughout the entire country. The evolution of fashion and the distinctions in thobe styles are best understood within a geographical context that prioritises a woman’s regional identity. Tatreez symbols should be studied within the same frameworks as the thobe, emphasising how women and girls carefully and artistically crafted their identities in both private and public spaces. Handmade embroidered garments were integral to daily wear as well as ceremonial attire, each motif carrying a story, a riddle, or a biography of the maker.

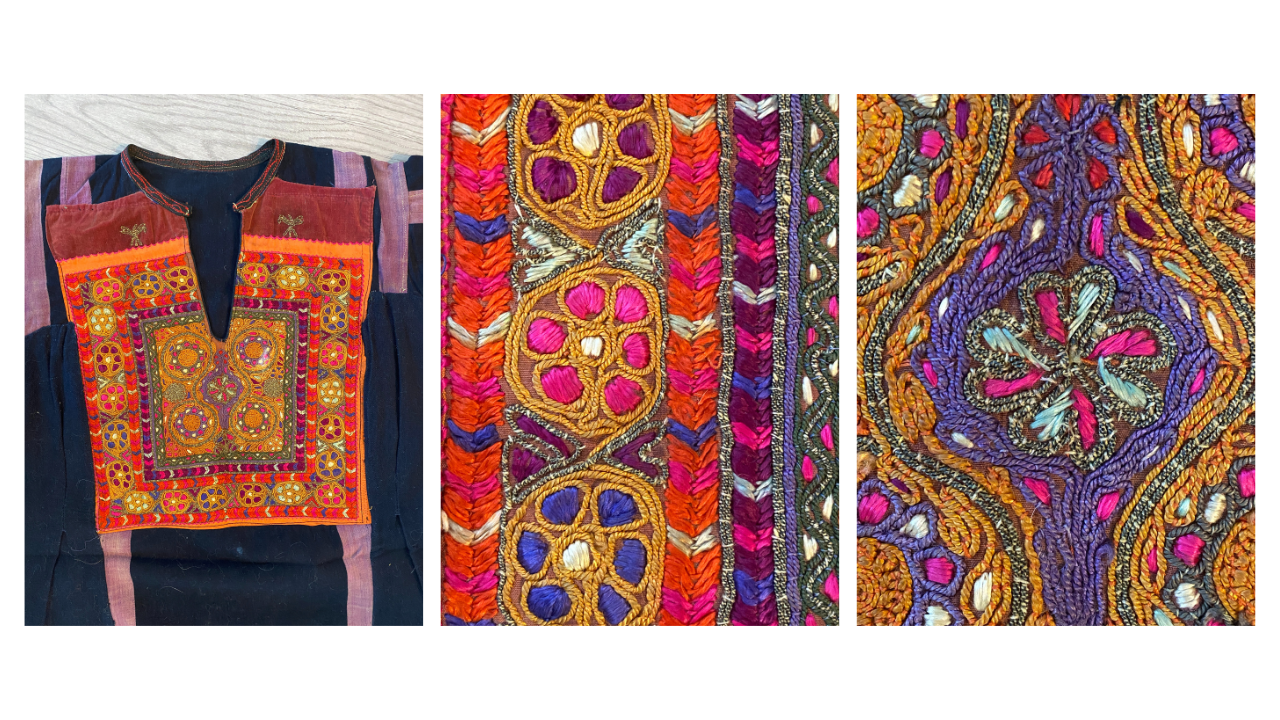

While GLISTEN was inspired by Southeast Asian Songket and Māori Tāniko weaving patterns, these same designs are also among the oldest motifs found in Syrian, Jordanian, Lebanese, Egyptian and Palestinian tatreez. They also appear across Southwest Asia and North Africa on stone, mosaic, architecture, metal and woodwork, dating back to antiquity.10 In GLISTEN, the patterns include stars, rosettes, diamonds and zigzags—each carrying distinct Indigenous interpretations depending on the culture.11 For instance, the shapes commonly referred to as stars, gilded in gold throughout GLISTEN, were stitched into tatreez motifs until the mid-20th century under various names in historic Palestine. In Bethlehem, they were called “crushed sugar,” in Yaffa, “stars,” in Ramallah, “moons,” and in Gaza, “roses.”12 As with many commonly used patterns across historic Palestine, the star was added to the thobe to ensure protection for the wearer. Arab embroidery samples from the Fatimid period (10th–12th centuries CE), as well as those of the Mamluk era (13th–16th centuries CE), feature the eight-pointed star prominently in samplers and clothes using cross-stitch and running stitch.13 In songket, the same shape is identified as a lotus flower, deeply important to Malay culture and religion. Depending on whether the flower has four or eight petals, it can symbolise different levels of existence.14

Eight-petalled motifs are also found in GLISTEN and can be found innumerably in tatreez as flowers (zahra) and rosettes. In Palestinian iconographies, the rosette is an ancient symbol that, at times, was interchangeable in meaning and reference with the eight-pointed star. In ancient Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Iran, Turkey, Syria and Kuwait) both the eight-rounded (rosettes) and eight-pointed (stars) shapes appear in a variety of objects, including anthropomorphic representations. While they are not necessarily equivalent in meaning or symbolism, at times what looks like a rosette is referred to in the literature as a star. Both motifs are widespread in the ancient world—for example, one can find in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection a Syrian-style figure of a female head found in an Assyrian palace at Nimrud with an embroidered rosette on her headdress (8th century BCE), a Canaanite figure of a seated goddess with a rosette on the top of her headdress (14th–13th century BCE), as well as an Assyrian cylinder seal that shows a statue of the goddess Ishtar with a starred crown (late 9th–early 8th century BCE).

Interestingly, in these examples, the eight-rounded and eight-pointed shapes appear specifically as adornments on the headdress, representing the status of an individual or deity. The same social function of the headdress was retained by both women and men in the region until the mid-20th century. By the early 20th century, flower and rosette motifs in tatreez displayed a significant variety of floral types and visual compositions. A motif similar to the rosette, created using the same stitch count, was also known as the “bottom of the coffee cup,” referencing the shapes left in the coffee grounds after drinking Arabic coffee. When flipped upside down to dry, these patterns were interpreted by elders as part of the cultural traditions of Southwest Asia and North Africa for fortune-telling.15

In songket weaving, and in the context of GLISTEN, the eight-petalled shape is a fruit with a colourful centre. An old Malay proverb states, “Black is the shell, but the sweetness lies inside,” reminding us not to judge a person’s worth or character by outward appearance alone.16 This proverb offers a powerful lens through which to examine the layered meanings embedded in Palestinian embroidery, where tatreez motifs and structured patterns are never merely decorative — they carry hidden elements of cultural, social and personal significance. On one level, this principle reflects a broader aesthetic and moral philosophy shared across many Indigenous arts of Southwest Asia and North Africa: the understanding that beneath traditional technique and formalized designs lie encoded messages of identity, ritual and lived histories. In the context of tatreez, this is especially evident in the geometric and floral motifs that adorn the thobe, conveying information about a wearer’s wealth, social status, and regional affiliation.

Echoing the proverb’s warning against judging by surface alone, tatreez functions as both a form of ornamental beautification and a repository of communal memory. Motifs such as the eight-pointed star or rosette, while appearing as ornamental flourishes, have for centuries served as symbolic markers of a woman’s identity and lineage. This dual role—as both beauty and knowledge—reflects the proverb’s tension between external form and internal meaning. Moreover, as seen in patterns like the “bottom of the coffee cup,” drawn from fortune-telling practices using coffee grounds, the same visual shapes circulate between everyday rituals and formal embroidery, entwining personal meaning (private) with collective cultural knowledge (public). Just as the proverb suggests that sweetness is contained within the black shell, the dark backgrounds of Palestinian dresses often serve as the base for vibrant, colorful stitches—preserving stories and meanings held within layers of paradox: dark and light, beauty and knowledge, public and private. Like the eight-petalled fruit motif in songket weaving, which holds a colorful center, Palestinian embroidery offers a “fruit” of collective wisdom—affirming that these seemingly opposite meanings can coexist—quietly asserting presence even amid loss. Through this lens, tatreez becomes not only an art form but also a record of embodiment and expression. Without one, there cannot be the other.

GLISTEN was more than a larger-than-life visual immersion of mosaiced art that memorialised Indigenous weaving traditions. It is an archive of symbols, bringing memory, inheritance and reclamation to the forefront and speaking to Indigenous histories both ancient and contemporary. The patterns that are also used in tatreez represent the continuity of culture against all odds, carrying the voices of Palestinian women across centuries. The same motifs that once adorned thobes in Bethlehem, Yaffa, Ramallah and Gaza—marking status in ancient Mesopotamian headdresses—now glow in the sunlight, embodying the indomitable spirit of Indigenous weavers and embroiderers. But just as tatreez has never been merely decorative, GLISTEN was never merely an installation. It was a reminder that beauty and grief, heritage and resistance, past and present, are profoundly interwoven. The motifs reflected in GLISTEN—stars, rosettes and geometric forms—are among the oldest symbols in Palestinian cultural heritage, preserved through tatreez and other arts, connecting us to a vast constellation of global Indigenous traditions. These patterns, stitched by Palestinian women, carved into ancient architecture and woven into textiles from Southeast Asia to North Africa, hold the knowledge and histories of people who have long resisted erasure.

Standing before GLISTEN, I watched the sun’s reflection shimmer alongside the tears in my eyes, heavy with grief. I was reminded of the Arabic proverb, “Sunshine all the time makes a desert” (kathrat ash-shams tasna‘u ṣaḥrā’), which teaches that hardship, however difficult, is essential as it is both a test and a source of strength. The genocide in Palestine was unfolding before the world’s eyes, and I spent nearly a year witnessing unbearable suffering, the destruction of homes, the loss of entire families, the suffering of my people—whose lives, heritage and history should have remained untouched under the world’s defence. In that moment, GLISTEN became more than a sculpture; it was a reflection of the beauty that endures even in the face of hopelessness and tragedy. Its patterns, evoking tatreez symbols, transported me home, to my ancestors and to the stories sewn into every stitch of my thobe—stories of survival, identity and unbreakable ties to the land, no matter how far away we are. Immediately, GLISTEN became an entity that was in dialogue with me, inviting me to listen, quieting my mind and asking me to look closer. As I heeded her call, I began to understand: the coins that sparkled in the breeze were also 114,000 tears, weeping with me.

No act of imperial conquest can erase the identities of women embroidered into their dresses, woven into fabric and stored in the collective memory of the Palestinian people now sprawled around the world. If history could be told through patterns, then we must look closer—because they are not only preserved in the threads of Palestine but woven into the vast fabric of Indigenous cultural traditions across the world. And just as GLISTEN is a tapestry of emotion—shining brightly while weeping softly through its shining medallions—so too must we exist fully in the paradox of the world, where beauty and grief are inextricably entwined and entangled, and yet, still glistening.

Notes

1. GLISTEN: Lisa Reihana, National Gallery Singapore, 2024. https://www.nationalgallery.sg/sg/en/exhibitions/glisten.html#about.

2. Rabea Eghbariah, "The Ongoing Nakba: Toward a Legal Framework for Palestine," NYU Review of Law & Social Change: The Harbinger 48 (2023): 1–20, https://socialchangenyu.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Rabea_RLSC-The-Harbinger_Volume-48-Piece-updated-2.25-1.pdf.

3. The Arabic term tatreez is generally translated as embroidery, or the ornamentation of cloth. Contemporarily and colloquially, tatreez has become synonymous with Palestinian embroidery.

4. The geographic boundaries of Palestine, referred to in this essay, is defined as the land east of the Jordan River and west of the Mediterranean Sea, bounded in the north by present day Lebanon and south by Al Naqab, or the Negev; See also “UNESCO – The Art of Embroidery in Palestine, Practices, Skills, Knowledge and Rituals,” UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, accessed 17 February, 2025. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/the-art-of-embroidery-in-palestine-practices-skills-knowledge-and-rituals-01722.

5. “UNESCO – The Art of Embroidery in Palestine, Practices, Skills, Knowledge and Rituals,” UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, accessed 17 February, 2025. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/the-art-of-embroidery-in-palestine-practices-skills-knowledge-and-rituals-01722.

6. “Feryal Abbasi-Ghnaim: Palestinian Embroiderer,” National Endowment for the Arts, accessed 17 February, 2025. https://www.arts.gov/honors/heritage/feryal-abbasi-ghnaim.

7. Widad Kamel Kawar, Threads of Identity: Preserving Palestinian Costume and Heritage, (Cyprus: Rimal Books, 2011), 1.

8. Wafa Ghnaim, “Tatreez in Time,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 26 July, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/tatreez-in-time.

9. Shelagh Weir, Palestinian Costume, (Northampton: Interlink Books, 1989), 17.

10. Hanan Karaman Munayyer, Traditional Palestinian Costume: Origins and Evolution (Northampton: Olive Branch Press, 2011), 36.

11. The United Nations defines “Indigenous” as communities, peoples and nations who have "historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories" and "consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them."

12. Grace Crowfoot, Embroidery of Bethlehem, Embroidery Magazine No. 15, 1925; see also Widad Kawar, The Traditional Palestinian Costume, Journal of Palestine Studies 10, no. 1 (1980): 118–29, 125; see also Palestinian Embroidery Motifs: A Treasure of Stitches 1850-1950, 2007, 165–169.

13. Munayyer, Traditional Palestinian Costume: Origins and Evolution, 36.

14. Qinyi Lim, ed., GLISTEN: Lisa Reihana, “Tāniko and Songket,” (National Gallery of Singapore, 2024), 43.

15. Margarita Skinner, The Journeys of Motifs: From Orient to Occident (Cyprus: Rimal Books, 2018), 147.

16. Lim, “Tāniko and Songket,” 43.