Reframing Modernism: Emiria Sunassa

The 2016 exhibition Reframing Modernism: Painting from Southeast Asia, Europe and Beyond explored new ways of looking at the history of modernism in art, through an encounter between the collections of the Centre Pompidou, National Gallery Singapore and other Southeast Asian collections. In this essay, reproduced from the accompanying publication, curator Lisa Horikawa examines the life and works of a pioneer in the modern art of Indonesia, Emiria Sunassa.

Detail of Papuan Archers, 1942

Oil on board

40 x 40 cm

Collection of Nasirun

This essay was originally written for the exhibition catalogue of Reframing Modernism: Painting from Southeast Asia, Europe and Beyond, National Gallery Singapore, 2016.

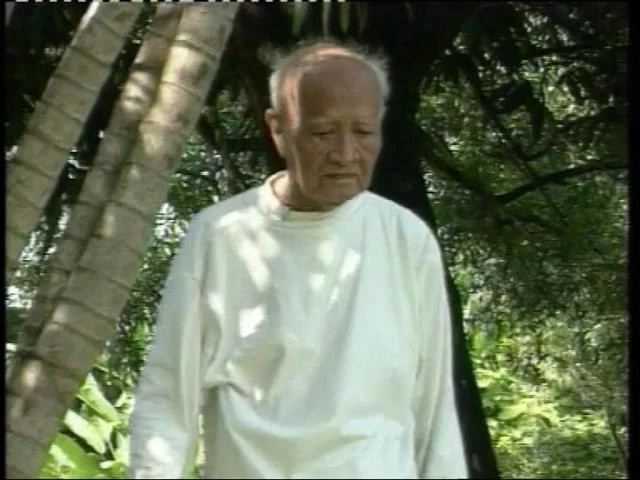

Myths abound in accounts of Emiria Sunassa.1 According to the oral and written histories unearthed by scholar Heidi Arbuckle, Emiria is recorded as a nurse (1912–1914), a student of eurhythmics in Brussels and Austria (1914–1915), a singer and pianist in Ternate (1920s), and someone who travelled widely across the Indonesian archipelago through the 1920s and 1930s working in plantations, mines and factories. During these travels, she mingled with diverse ethnic groups in Papua, Kalimantan and South Sumatra, and was remembered by those who claimed to know her as an elephant hunter, poison maker and the “tiger woman."2 While records are inconsistent, she was undoubtedly a pioneer of Indonesian modern art.

Emiria made her debut as a painter at the first art exhibition of native artists held at the Kolff bookstore in Batavia in 1940, and took part in the watershed exhibition of PERSAGI (Association of Indonesian Drawing Masters) at the Batavia Art Circle in 1941. During the Japanese Occupation, a magazine article on Indonesian artists preparing for an exhibition at the Keimin Bunka Shidosho (Centre for People’s Enlightenment and Cultural Guidance) featured a photograph of Emiria standing in front of an easel with a confident gaze, along with images of five other artists from the period, S. Sudjojono, Agus and Otto Djaya, Basoeki Abdullah and Kartono Yudhokusumo.3 The accompanying text reads: “her forceful touch and electric colours places her in a distinct position within the Indonesian art circle that has little sign of individualism,” signifying her unique positioning at that time. In all the exhibitions Emiria showed between 1940 and 1950, she was the sole female artist.

Emiria claimed to be a princess of the Tidore sultanate. Between the 1940s and 1960s, she was politically active in the struggle for Papuan independence from the Dutch colonial administration. In contrast to works by her contemporaries which tended towards social and mainstream nationalist interests, her works presented the concerns of people at the margins of the nation—ethnic groups on the eastern part of Indonesia and women. In all of her paintings from the 1940s and 1950s, she focused on those largely unrepresented in the grand national narrative of Indonesia, consistently using subversive approaches to unsettle the assumptions associated with the internal Other. In her earliest surviving work, Papuan Archers, the composition is dominated by dark hues. The stark contrast of the dark skin of the archers and their gleaming white teeth, their piercing gaze and the white of their eyes, generates a sense of unease. On the verso of the painting is a portrait of a Caucasian woman, presenting a jarring juxtaposition with the archers. Similarly, in Bahaya Belakang Kembang Terate (Danger Lurking Behind the Lotus), the taut moment of the archer with his bow drawn is captured in a dreamlike dark jungle studded with electric pink lotus flowers. The ethnic origin of the archer appears to be imaginary, with Emiria making visual references to several different ethnic groups in the archipelago. In Pasar (Market), tension is created through an everyday gesture: a female figure in the foreground, whose identity is concealed from the viewer, reaches her hand out to sample a produce.

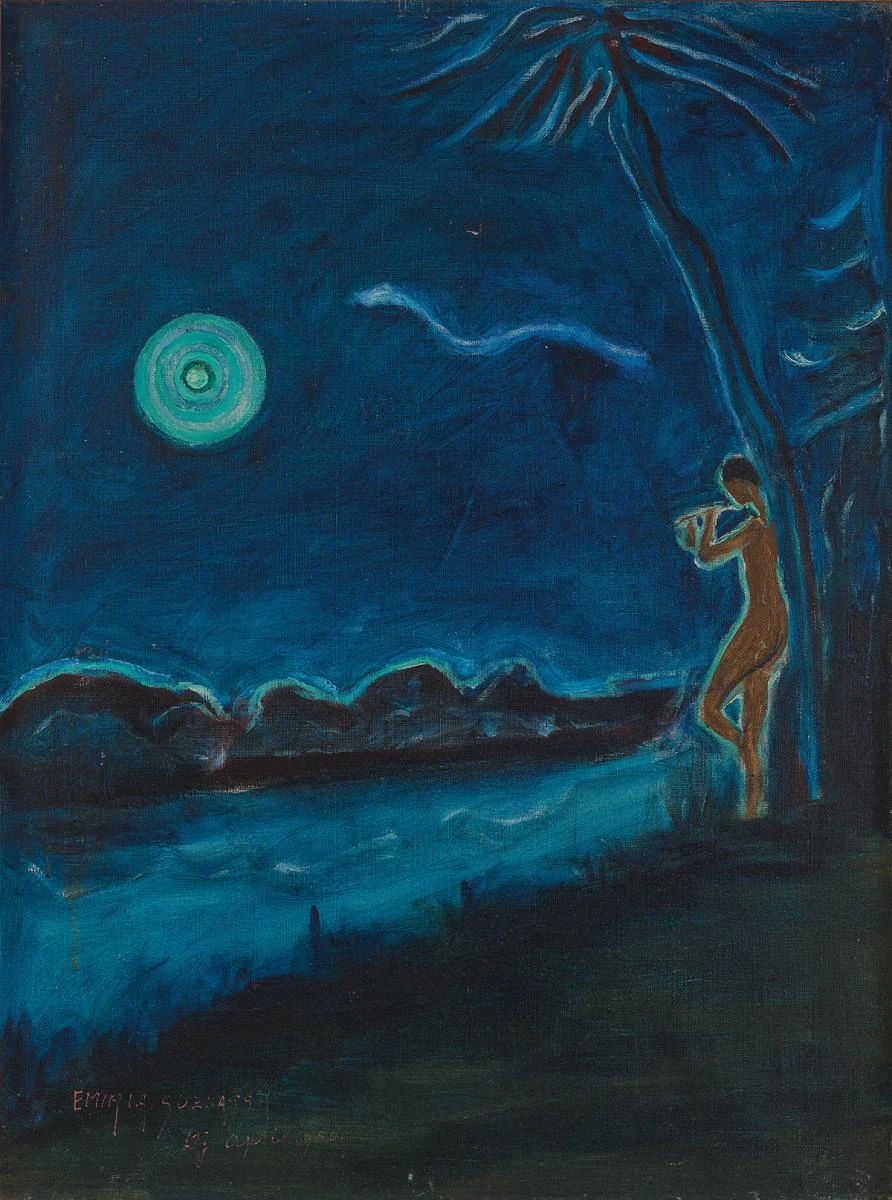

In Emiria’s later work Peniup Seruling dan Purnama (Flute Blower and Full Moon), completed in 1958, a solitary female figure stands in a fantastical nightscape veiled in rich shades of blue. Compared to her earlier works, the painting demonstrates a notable development in its fluidity of line.

Shortly after, in the early 1960s, Emiria disappeared from Jakarta. In July 1960, The Straits Times reported Emiria to be in Singapore and working to present her claim to the United Nations as the rightful monarch of West Irian,4 which was subsequently reported as dismissed by the Indonesian government.5 The complex subjectivity and reception of Emiria—as a female artist, self-proclaimed princess who struggled for the cause of Papuan independence, who experienced the tumultuous transition from the colonial period to independent Indonesia—has been relegated to near oblivion in modern Indonesian art history. Disrupting normative representation and female subjectivity, her works and extraordinary life are a resource for reconsidering the dominant and alternative imaginings of this history.

Editor's Note

Find more information and excerpts from the publication Reframing Modernism: Painting from Southeast Asia, Europe and Beyond here.

Notes

- In the publication Reframing Modernism, the artist’s name is printed according to the new system of Indonesian spelling adopted in 1972.

- For the most comprehensive research on this artist, see Heidi Arbuckle, “Performing Emiria Sunassa: Reframing the Female Subject in Post/colonial Indonesia.” (PhD. Diss., The University of Melbourne, 2011.)

- See “Exhibition of Paintings in Java,” Djawa Baroe, no. 9 (Jakarta: Jawa Shinbunsha, 1943), reprinted in Kurasawa Aiko, ed., Djawa Baroe 1 (Tokyo: Ryukei Shosha, 1992).

- Arbuckle, op. cit., see “RI: If claim proved she might be Queen of West Irian,” The Straits Times, 6 July 1960, 1; “Princess rejects ‘advice’ to keep claim out of UN,” The Straits Times, 29 July 1960, 9.

- Arbuckle, op. cit., see “Woman’s claim to throne ‘not genuine’,” The Singapore Free Press, 13 August 1960, 7.