out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 Debbie Ding

out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 is a special series of creative, critical and personal responses by artists on the significance of the coronavirus to their respective contexts, written as the crisis plays out before us. Debbie Ding searches for the answers to optimise work-life balance whilst juggling her latest project—a child.

Detail of Flatlands, 2020

Image courtesy of Debbie Ding

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

Is productivity truly productive? What does it mean to work as an artist in this time of crisis? While in isolation, Debbie Ding sought the answers to optimise work-life balance whilst juggling her latest project—a child. Debbie is a visual artist and technologist who researches and explores technologies of perception through personal investigations and experimentation. Her work focuses on prototyping, a conceptual strategy for artistic production that iteratively explores potential dead-ends and breakthroughs in the pursuit of knowledge.

What Keeps Us Making? Art, Motherhood, and Productivity

Debbie Ding

I

Productivity and art are not words that usually go together. Art can be poetry, art can be incomplete and imperfect, art can be raw and a process, art can be intangible or ephemeral in ways that are impossible to pin down; art can’t be readily measured in calculable outcomes. Yet when all else grinds to a halt, we find ourselves wondering: what keeps us making? What keeps us working? Why do we make work?

Some might say that I’ve been obsessed with working all my adult life, always having several projects on the go. I’ve even worried that my obsession with “always working” might be a “Singaporean thing.” As the endless noise of construction floods in through my windows, I have often wondered if I have spent so long in Singapore’s system, built upon continuous work and progress, that I have internalised the notion that hard work is a virtue in itself?

There is tonnes of self-improvement literature online: lifehacks, mental frameworks, an entire rash of Medium articles, some written by machines. As someone used to working a day job alongside making my art, part of the territory of trying to multitask is an interest in productivity systems. You name it, I’ve probably read it: Cult of Done, Getting Things Done (GTD), Pomodoro Technique, Eat That Frog, Pareto Principle, Bullet Journaling, Stoicism 101, meditation, mindfulness, Second Brain, PARA Method, Zettelkasten, Agile, Scrum, quantified self-trackers that collect all sorts of data to analyse where your attention is leaking…

I said I was into productivity, but this is mainly because I procrastinate a lot. (This article, for example, is very late! Apologies to the editors.) Prior to the pandemic, I had two “jobs”—my day job, and my art. To add to the mountain of the work I was already doing, I took on a new decades-long project—raising a tiny human being! Babies, particularly when they are small, are probably one of the most ambitious, complicated projects that one can embark on.

Not only is parenting an unpaid job, there are even more bills to pay. There are the basics such as clothing, shoes, carriers, food, milk, diapers, car seats, strollers. And beyond the basics, a world of technological innovations to help new mothers on top of all the domestic work and child-rearing–along with everything else that women do before they have children.

The source of my guilty pleasure quickly changed from systems that enhance productivity, to genres of YouTube videos I never knew existed: “HACKS FOR PACKING SNACKS,” “How I pack my jujube brb diaper bag for a newborn and a toddler in diapers for quick outings!,” “BEST baby nasal aspirators 2020!”

You would think that with all these hacks I’d have optimised my life to do it all. But instead, I found that any free time I saved was ploughed back into working. It is almost as if being productive is expected to be the intrinsic good itself that gives meaning to our lives. Why do I always catch myself saying “the right balance,” as if I exist on a scale that balances work and baby? Why can’t I do all the work I want to do, and do it with the baby strapped to me?

When the circuit breaker began, I could only picture in my head the sort of pandemonium depicted in disaster and catastrophe movies. But no. Besides a few long queues for toilet paper and rice, there was simply silence. Singapore had responded with a concerted effort to halt activities involving close social interaction, switched off large parts of the economy, closed the schools, stopped us from meeting friends and family. We were told to change how we lived overnight. And so we did.

What this shows us is that society as we know it is actually programmable. If society was an app, then you could say that the app developer was asked to disable several features of the app that couldn’t be run safely anymore whilst they rewrote other features, but some of the basic code was still allowed to run unmodified. If everyone was able to change their behaviour for the greater good in a pandemic, then couldn’t we have rewritten the way we do things for the greater good of society in other ways?

At this point, what does it mean to work as an artist? I write this from the position of someone who currently is a full-time employee in an institute of higher education. I am fortunate and privileged to have that security, but I have worked in more short-term, precarious employment in the past —as a full-time artist—and I know that it must be an incredibly difficult time to be working in the arts with exhibitions, performances, and interactive experiences restricted for the sake of public health.

COVID-19 has stripped bare the most pressing issues of long-term sustainability faced by so many artists—the lack of financial return from a creative practice that may have taken years, if not decades, to hone, the lack of long-term professional development and progression, the lack of time and space to do creative work due to everyday pressures and family commitments, the difficulty of growing and cultivating an audience. If this is not sustainable, we need to rethink how we teach and practice art.

II

COVID-19 has been a time for digital reinvention. There were many things that people said could not be done from home, but now that we cannot meet in person, we’re finding new ways to do things. Meetings, classes, workshops, festivals, screenings, gigs, and performances.

I’ve never liked being referred to as a “digital” artist or “new media” artist because I think artists should not need to delineate whether their artforms are “digital” or not. (And what is “new media,” and when does a medium get “old”?)

Even if an artist has made a painting or a sculpture or a work in a traditional medium, it is going to be photographed or captured on video and a digital version of the work will circulate through digital platforms, whether the artist likes it or not. Art will be mediated through screens and interfaces. This doesn’t have to be cast as a problem or pain point, but rather as an opportunity to expand the field of one’s artistic practice.

Artists should have a basic understanding of digital platforms, so that they can be involved in translating, producing and publishing their works into appropriate digital mediums to enable them to reach a wider, now-socially-distant audience. The act of translating a work to a digital medium, whether done directly by the artist or through collaboration, should be regarded as an important part of contemporary “art-working.”

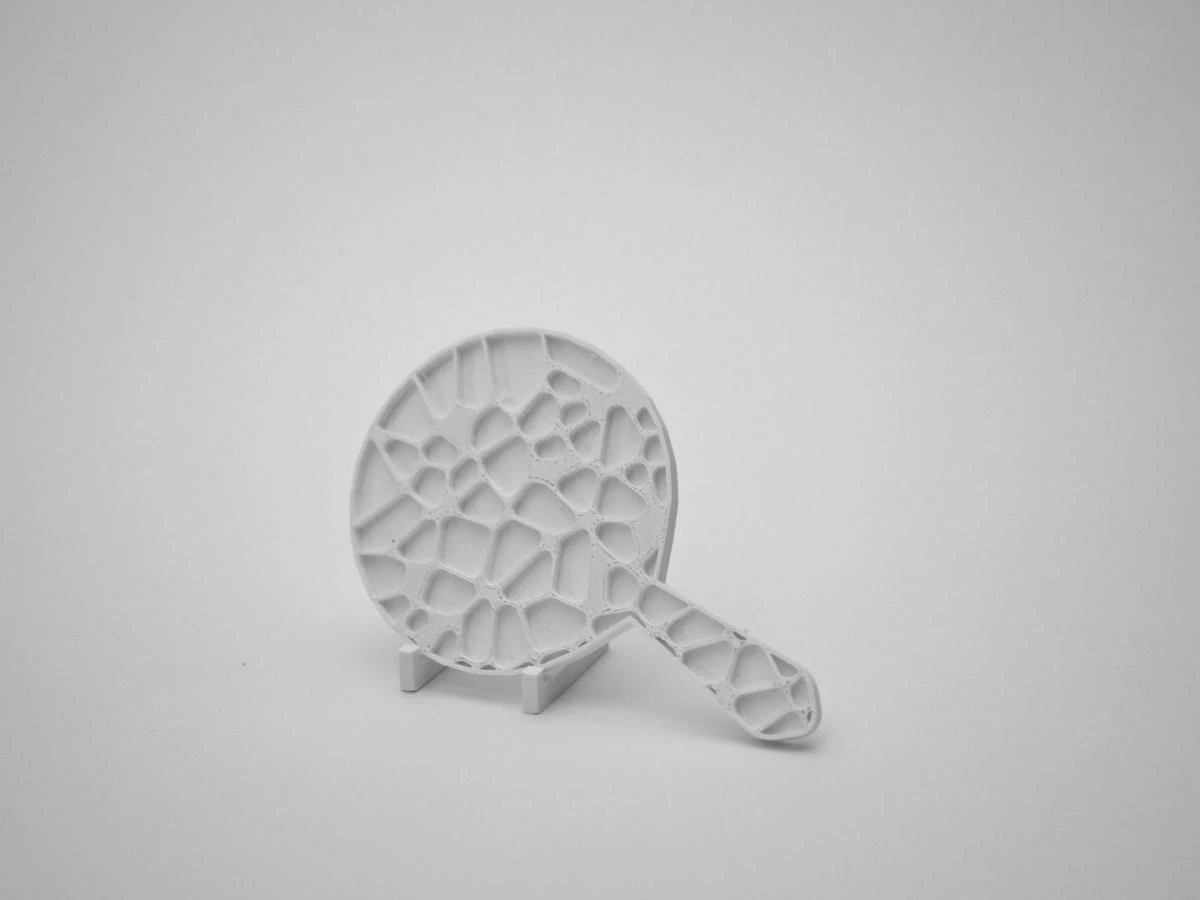

To me, finding the right medium for each work is an important part of the process. In the past, my experiments have led me to explore mediums such as 3D printing and rapid prototyping (the prototype is full of narrative potential!), holography (an obsolete visual technology medium being used once again for image-making!), and game development (the 3D game engine as a platform for exploring experimental interaction and narrative design!).

As an artist, I aim to be proficient enough in a certain technology to produce a conventional project to professional standards. After mastering the medium however, I choose to be playful with it. I want the work to be produced intentionally, never simply because I do not understand, or lack control over the medium.

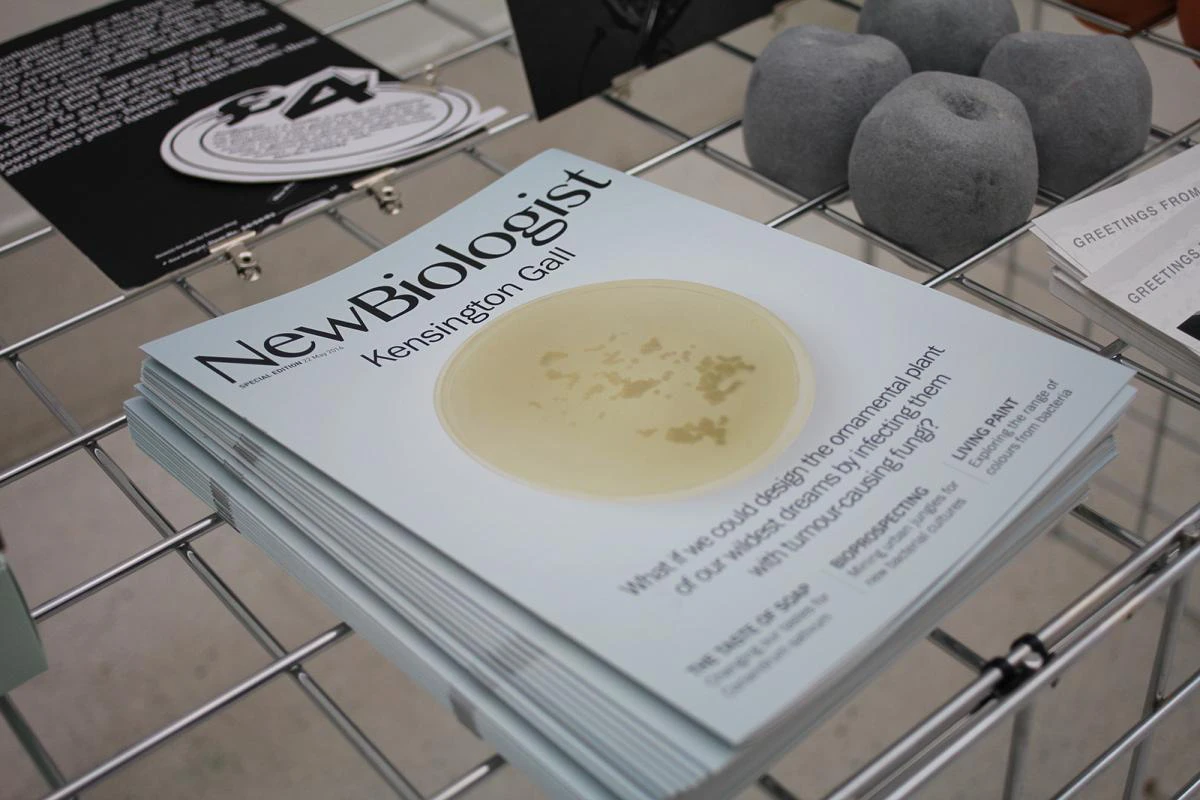

Debbie Ding, NewBiologist, 2014. Image courtesy of Debbie Ding.

Debbie Ding, The Library of Pulau Saigon, 2015. Image courtesy of Debbie Ding.

Along the way, I discovered the issues with different mediums. For example, through my experience with pulsed laser holography, I realised it likely fell out of popular favour because it is very complicated (no one understands what is happening even though the science has been thoroughly explained), very costly (it requires an optics lab, so not quite a medium to be used for everyday images), and you have to light the work from a specific angle and stand in a specific place to properly perceive the image on the holographic plane (audiences don’t like to be told to stand in just one spot to see the image!). It does explain why holograms are generally regarded as anachronistic and retrofuturistic today, but the medium’s cultural history and obstinacy also attracts me to it.

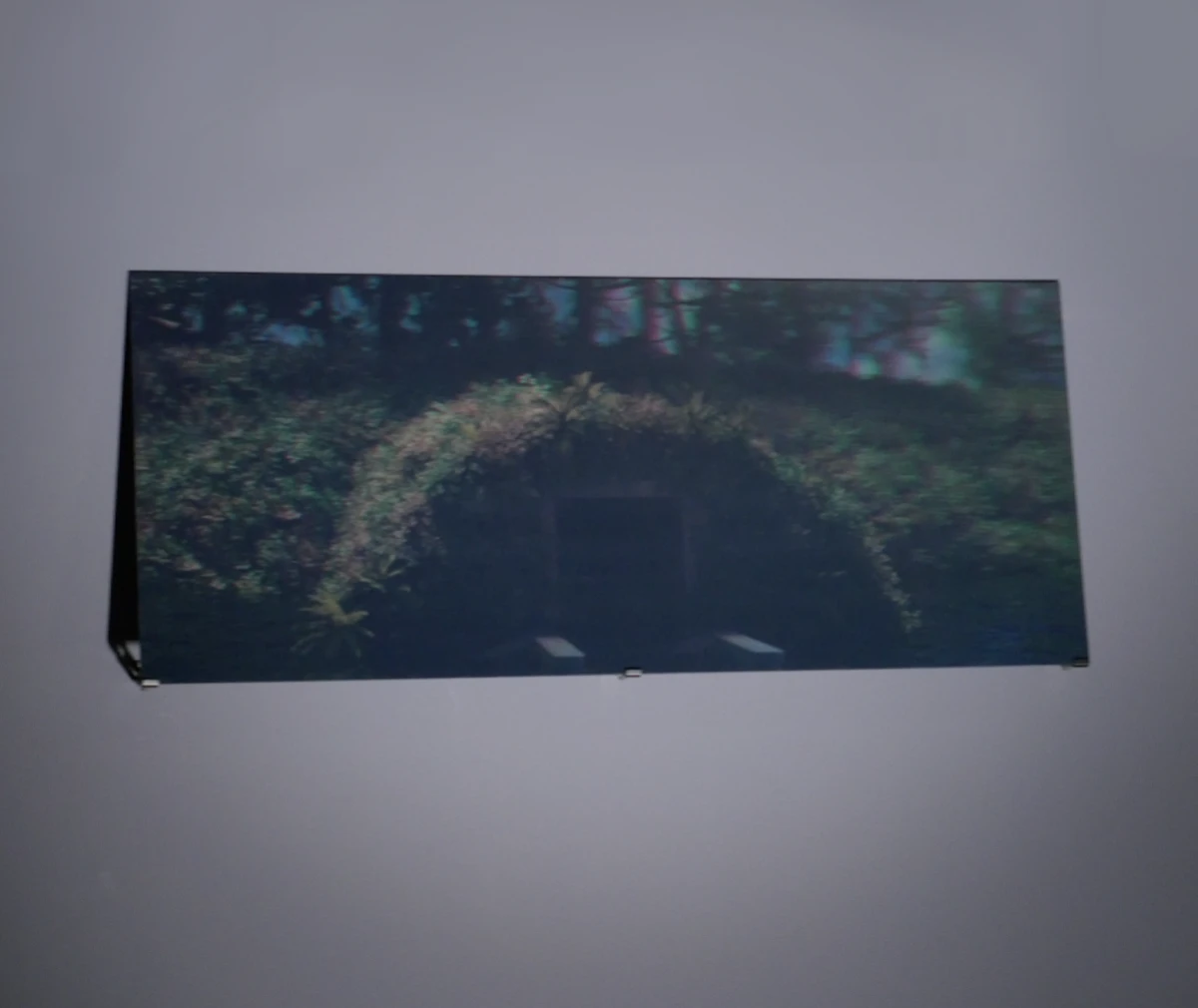

Debbie Ding, War Fronts, 2016. Image courtesy of Debbie Ding.

The whole process of finding the right medium is frequently hit-and-miss. It is okay to produce complete duds and weird mashups and “minor works”; that’s part of the process of creation. The failures, mistakes and errors—I keep them all.

Debbie Ding, Paintpusher, 2020. Image courtesy of Debbie Ding.

In times like these, art, literature, music, and culture become even more crucial in showing us alternate possibilities for the world we want to live in. By producing a new visual image, we force the viewer to see a different perspective, and make new readings of our own world.

Being the mother of a small baby and with the precautionary COVID-19 measures, I’ve been forced to turn to digital projects; I’ve spent time thinking about how I would translate the presentation of my assemblages and collections of physical objects to the digital.

Debbie Ding, Flatlands, 2020. Image courtesy of Debbie Ding.

At first, I tried to find ways of arranging works in a space, in a direct translation of how we position objects in the real world, but recently I’ve been visualising the collective body of my work instead as a dynamic column, a different kind of living archive, one that I could query for answers.

A work in progress (Mobile app, 2021)

MOTHER is always on display

MOTHER is a repository of experiences

MOTHER is still busy trying to digest and process everything

MOTHER will never be finished with work

MOTHER is somehow always close but also far

MOTHER will speak and interact with you when your battery is low

MOTHER will try to answer your questions

MOTHER doesn’t have all the answers, but

MOTHER will comfort you

Image courtesy of Debbie Ding.

When you produce an artwork for another time and place, then surely the search for new mediums of expression shouldn’t stop at the traditional. As artists, we need to learn from one another through collaboration, and grasp the full potential of the digital technologies available to everyone.