out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 AWKNDAFFR

out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 is a special series of creative, critical and personal responses by artists on the significance of the coronavirus to their respective contexts, written as the crisis plays out before us. In the shadow of the onslaught of monumental events that have occurred in the space of a year, AWKNDAFFR investigates how we might move forward from the contemporary condition of exhaustion in this email to a friend. How should we recall joy, care, and pleasure in the multitude of jobs and titles and identities that we hold, amidst this crisis-laden, exhaustive condition of the present?

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

In light of the onslaught of monumental events that have occurred in the space of a year, AWKNDAFFR investigates how we might move forward from the contemporary condition of exhaustion toward a new mode of existence: pleasure. How should we recall joy, care, and pleasure in the multitude of jobs and titles and identities that we hold, amidst this crisis-laden, exhaustive condition of the present? How can pleasure be produced by labours that operate outside modes of relation in which exhaustion is the currency of exchange?

AWKNDAFFR is an artistic operation which situates itself at the intersections of art, theory, and praxis; disentangling and deviating from complex contemporary conditions of capitalism and coloniality. Its first interpellation was A Weekend Affair, a two-day rendezvous in June 2019, and more recently, was part of The Substation’s Associate Artist Programme 2020. AWKNDAFFR is currently working on a publication titled Other Options (2021), co-edited by Wayne Lim, Soh Kay Min and Diana Rahim.

MMXXCCOO

AWKNDAFFR

Re: Contribution to ‘out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19'

from: <no-reply@nationalgallery.sg>

to: <awkndaffr@gmail.com>

date: May 11, 2020, 4:13PM

from: <awkndaffr@gmail.com>

to: <no-reply@nationalgallery.sg>

date: October 20, 2020, 20:20

Dear ______,

Time is a funny concept. Somehow, by some arbitrary measure, today is the eighteenth day of the tenth month of the twentieth year of the twenty-first century. We’re terribly late in writing this letter. We were asked, on the eleventh day of the fifth month of the same year, to respond to the then-new series, out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19, initiated by the National Gallery Singapore.

I think we were meant to have responded by the twenty-first day of the eighth month of the year.

We were told that the series hoped to bring together “critical responses and personal reflections by artists and cultural workers on the significance of the coronavirus pandemic to their respective localities and contexts.” The day that we were made aware of this hopeful initiative—the eleventh day of the fifth month of the twentieth year of the twenty-first century—was the thirty-fifth day of the nation-wide Circuit Breaker1, which was announced on the third day of the fourth month of the year, and enacted four days later, on the seventh day of the month.

Recalibrate the passage of time—this time, to the timeline of the coronavirus pandemic we were asked to respond to. The beginning of the Circuit Breaker on the seventh day of the fourth month of the twentieth year of the twenty-first century was the seventy-fifth day since the confirmation of the first person in Singapore to be infected with the disease. The virus was first said to have travelled through a wet market in Wuhan in the twelfth month of the nineteenth year of the twentieth century, transmitted through Chinese whispers and digestive tracts and wild water particles flying between bats and pangolins and fish and humans. It took a hundred and seven days for the frequencies of the virus’ whispers to be detected on a global wavelength. Time jumped, tripped across an imperceptible boundary, and suddenly we found ourselves in the twentieth year of the twenty-first century. On the eleventh day of the third month, the virus was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation.

On the seventh day of the fifth month of the same year, we were late again. This time, to restart a conversation with S., whom we had last met on the first day of the fourth month of the nineteenth year of the twenty-first century. A strange time-trip, time in Double Dutch, a squaring of timelines to unfold a multiplicity of sequential realities. S. wrote us back on the eleventh day of the sixth month of the twentieth year of the twenty-first century, about the Black Lives Matter protests in the United States that had entered their sixteenth day, that had begun on the twenty-sixth day of the fifth month of the same year. The struggle continues.

S. noted that despite their international momentum and visibility, the protests inside the United States were very much tied to the country’s particularities, history, and current political moment. But that they were, and continue to be, tied to the global pandemic. He had shrewdly quipped that in the way it strikes, the virus is like an ultraviolet ray that illuminates systemic racism and colonialism, and lights up the gender, sexual, and class exploitation making so many nations “work.” And it glows in the face of would-be fascists and neo-fascists and their ghoulish, death-driven minions.2

Before and between the emails from S., a multitude of things Happened and continue to happen. Time slipped and stumbled in and out of Phase One of post-Circuit Breaker. On the fifth day of the fourth month of the year, a four-year-old Malayan tiger contracted coronavirus at the Bronx Zoo in New York. On the sixth day of the fifth month of the year, some of our fellow planetary beings located the closest-known black hole, which is about one thousand and eleven light years away from our solar system, residing in star-system HR six thousand, eight hundred and nineteen, which is visible to the Earth-bound eye. So I’ve heard, but what’s that gotta do with this black hole and me? Currently, it seems we might be in Phase Two-Point-Seven-Five-Nine-One-Six-Two within the seemingly infinite scale of Dorscon Orange, wherein the government simultaneously rolled out several plans and resilience packages to artificially stimulate the economy and cushion the impact of the bioeconomic crisis. With air travel halted, dystopian-like control measures as robust as the health surveillance system now appear to be more than necessary in curbing and suppressing the transmission of COVID-19. The threshold keeps increasing, the crisis keeps prolonging. Time and its forms of measurement are looking more and more capricious… What comes next?

What do we give attention to? We don’t want to overwhelm you like the abyss of blackhole HR six thousand, eight hundred and nineteen might, but in the second month of the twentieth year of the twenty-first century, the pandemic caused the fastest-falling stock market crash in financial history. On the fourth day of the eighth month of the year, a chemical warehouse exploded in Beirut, causing over 200 deaths, 6,000 injuries, and 300,000 left without homes. On the sixth day of the ninth month of the year, a gender reveal party in Southern California sparked a fire that caused the evacuation of over 20,000 people. Time kept dropping. Protests in all shapes and sizes erupted across the planet, with some still ongoing in the United States, Thailand, and Hong Kong. War is tearing communities apart in armed border conflicts in China-India, and Armenia-Azerbaijan. A student coalition seeks to form a Tribunal to investigate the ongoing genocide in Uyghur. Ecological crises range from wildfires in New South Wales, Chiangmai, California, to the Amazonian forest that has been burning since 2019, to a 1,000-tonne oil spill over the reefs of Mauritius, to multiple typhoons that have devastated crops and resulted in a South Korean “kimchi crisis.” As the climate crisis continues to deepen, artists Gan Golan and Andrew Boyd had an “earth’s deadline” (a climate clock) installed in New York. A string of pandemic elections continues to jeopardise the world. It is now the sixth day of the eleventh month of the twentieth year of the twenty-first century, a swollen and distended moment expanded and extended across the past one hundred and seventy-six days. I suppose you can tell by now, we are hardly fast, or first responders.

Several spatiotemporal jumps in Time’s enduring game of Double Dutch. We arrive again at the eleventh day of the fifth month of the twentieth year of the twenty-first century. Back to “work.” We were asked, in the middle of a broken circuit, what kinds of inequalities and injustices our social and economic system the current crisis has laid bare, and what changes people want to see? If the origin of the virus is bound up in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever?

Now more than ever, it feels strangely dissonant to be asked these questions in the context of “work,” as cultural producers and art workers taking a fee to respond to planetary questions huge and unanswerable, as part of our sometimes-jobs/always-occupations. To be asked questions we have no answers to, only to unearth more painfully banal questions: How do I know if I’m a “self-employed person?" How do I know if I meet the eligibility criteria to receive financial aid from the state due to loss of income? How do I prove that I have lost this elusive “income” when it comes and goes and only sometimes stays? How do I re-constitute myself to accept Humanity as pure Capital? Who am I proving myself to? Who is responsible for answering these questions? Who is responsible for answering those Questions? Is it part of my job to answer those Questions?

The direction of a question with the expectation of an answer, in the context of a job-related responsibility, feels like an oddly ineffective model. While email enquiries go unanswered, a stranger in a group chat might offer another opening—perhaps not always an answer, but sometimes ears that hear, a voice that responds, supporting legs that go on grocery runs when for whatever reason, you can’t walk out your own front door. And always, necessarily, without an expectation of a return or assumption of a result. As Hito Steyerl emphasises: “An occupation is not hinged on any result; it has no necessary conclusion. As such, it knows no traditional alienation, nor any corresponding idea of subjectivity. An occupation doesn’t necessarily assume remuneration either, since the process is thought to contain its own gratification. It has no temporal framework except the passing of time itself. It is not centered on a producer/worker, but includes consumers, reproducers, even destroyers, time-wasters, and bystanders—in essence, anybody seeking distraction or engagement.”3

With this in mind, we can’t help but ponder what might constitute work and labour in the near future. How should we recall joy, care, and pleasure in the multitude of jobs and titles and identities that we hold, amidst this crisis-laden, exhaustive condition of the present? As we move forward and backward and sideways with Time, we’d like to share a Question that has been occupying our time: how can pleasure be produced by labours that operate outside modes of relation in which exhaustion is the currency of exchange?

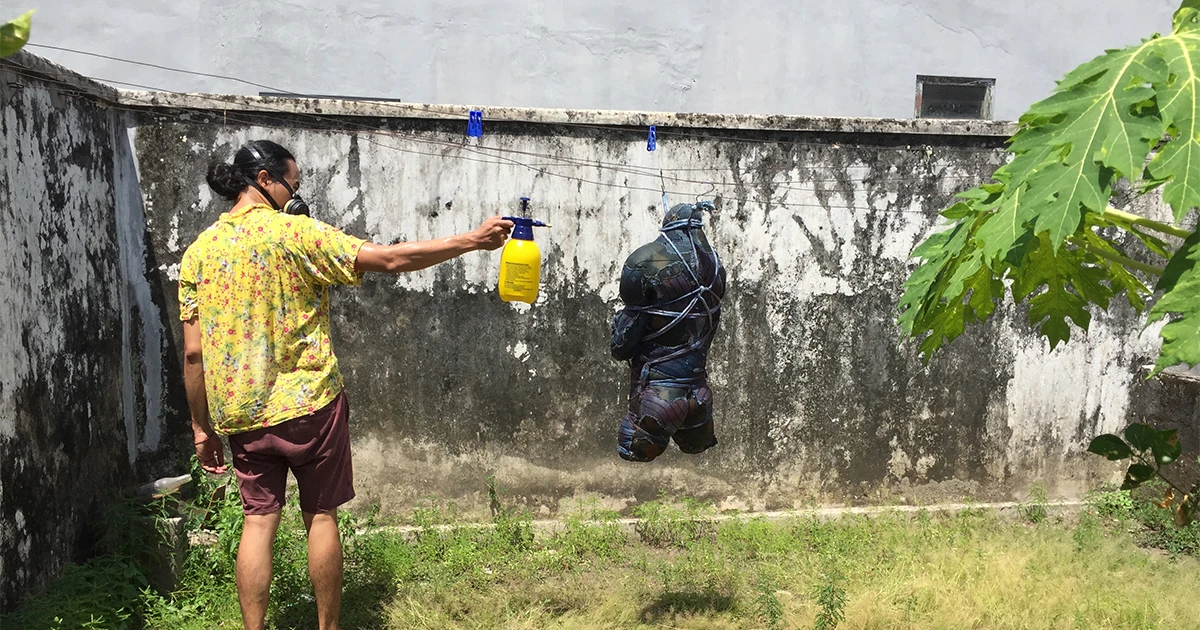

Energy is a limited resource. Its inevitable exhaustion is felt as a deeply personal incapacity to consolidate and build the autonomous forms of agency we crave. The specific sociopolitical context of Singapore enforces the confines of the “can” or “cannot;” a stifling environment that strictly limits possibilities of action, autonomy and alterity. It becomes increasingly apparent that efforts to gather and organise have to occur within in-between spaces with a strategy of covertness in order to activate methodologies of care. Perhaps it is never the intention to cheat the system, but as one continues to navigate the “can’s” and the “cannot’s,” an energy starts to accumulate; a restlessness sandwiched between the visibility of “can” and invisibility of “cannot.” As opposed to the hypervisibility—and at times the spectacle—of allyship, what does it mean to be an accomplice in an operation? What does it mean to exercise care for others in unseen and private moments of exhaustion, tied up and entangled between the threads of capital and its neoliberal hangovers?

However, as COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc around the world, unemployment rates are increasing, airlines are clipping their wings, millions of low-wage labourers are going to the frontlines without any form of security, and no amount of capital seems to be enough to soften the blow from the crisis, the answer of where to go from the point of exhaustion is thus: towards pleasure . To break from the binary of the “can” and “cannot,” and to inhabit the space of the in-between, is to access this joy, found in moments of spontaneous, collective cooperation. In order to access this pleasure, however, we have to interrogate the power dynamics that have defined and denied our pleasures—such as the ones found in our own labour, and with each other. It is necessary to liberate oneself from the conditioning and the belief that we can only relate to each other by competitive, alienating or “profitable” ways.

In order to resist the logic of human capital, it is fundamental to recognise the interdependence of coloniality and capitalism—one needs the other to maintain hegemony. To deconstruct both, exchanges between people, groups, or communities must go beyond capitalising on one another. Understanding that it would also be too naive to call any form of labour and effort within the operation to be an act of love (too soon), the hope is to transpire toward a transformation of modes of creative labour that are distinct from transactional and product-driven collaborations. In the midst of this prolonged crisis, the task is to recover what living together and participating in acts of communal care can provide outside endless permutations of systemic labour exploitation and further social alienation generated by the global condition of financial austerity.

Time skips again across borders and vast empty spaces. As Yuk Hui wrote, “True co-immunity is not abstract solidarity, but rather departs from a concrete solidarity whose co-immunity should ground the next wave of globalisation (if there is one).”4 It is not only a set of relations that defies the mode of capitalist (re)production, but effort and time set aside for the strengthening of friendships, seeking (new) affinities, and aiding accomplices. Participating and living together in forms of sociality demands an intentional and operative orientation towards active and present forms of communality. Instead of models of community-building oriented towards a future that is already slowly being cancelled5—which risks neglecting a present of care for its members—perhaps a politics of care is the answer to your Questions.

With love,

AWKNDAFFR

Notes

- The 2020 Singapore circuit breaker measures, abbreviated as CB, was a stay-at-home order and cordon sanitaire implemented as a preventive measure by the Government of Singapore in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the country on 7 April 2020.

- To S.: Thank you for your words, your presence across seas. We seem to have lost track of time again, but we did receive your most recent email. We’ll write you back soon, it’s a promise. We’re thinking of you.

- Hito Steyerl, “Art as Occupation: Claims for an Autonomy of Life,” The Wretched of the Screen (Sternberg Press, 2012), 103.

- Yuk Hui, “One Hundred Years of Crisis,” e-flux Journal #108, April 2020, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/108/326411/one-hundred-years-of-crisis/.

- Franco “Bifo” Berardi, “The Century that Trusted in The Future,” After The Future (AK Press, 2011), 39.