Notes on Photography: Wu Peng Seng

Curator Charmaine Toh explores the aesthetic qualities of pioneer photographer Wu Peng Seng’s images, offering fresh insight into his practice.

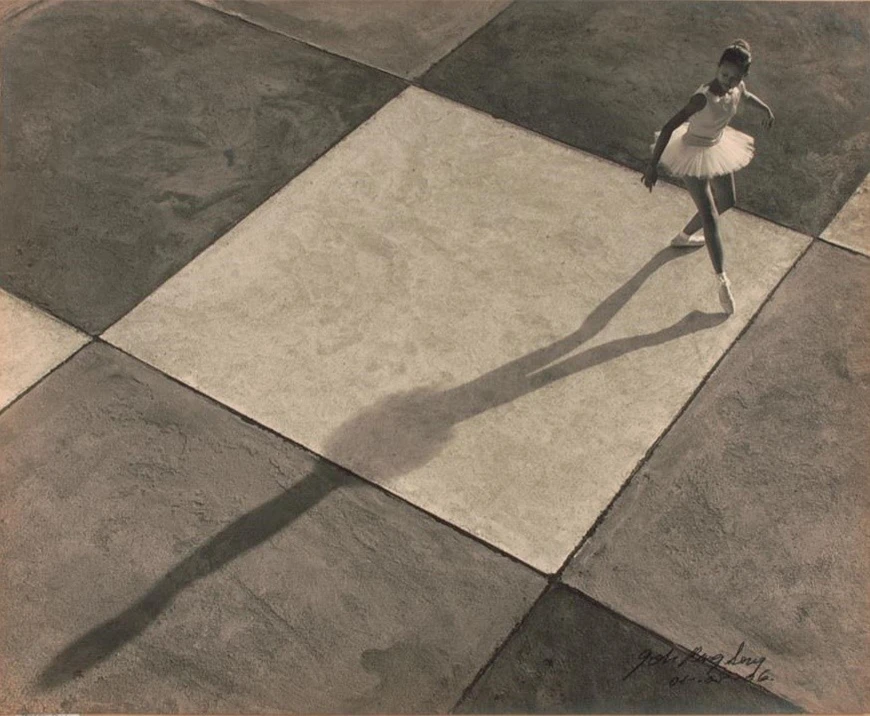

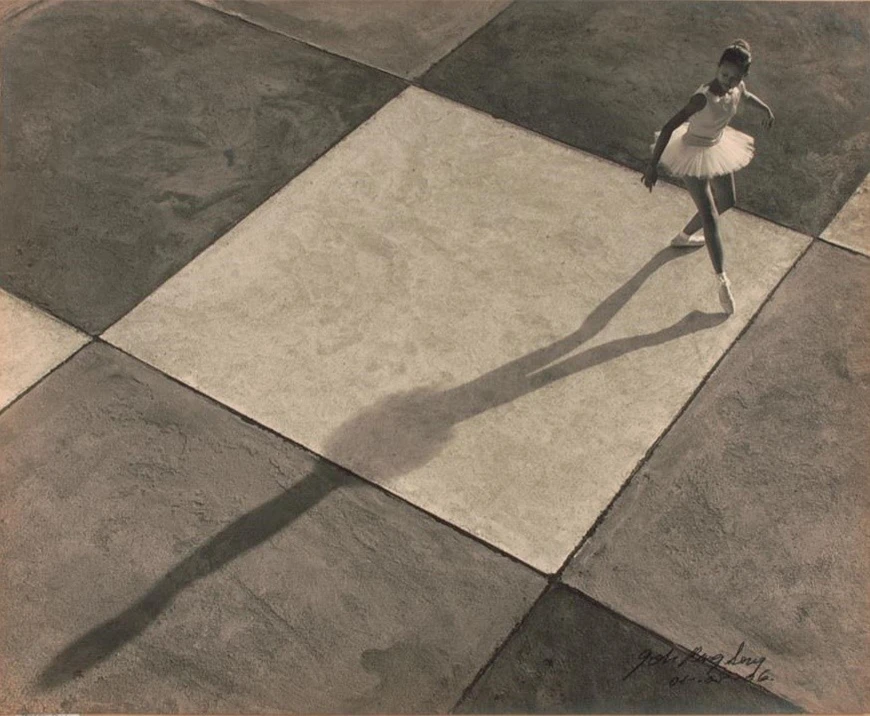

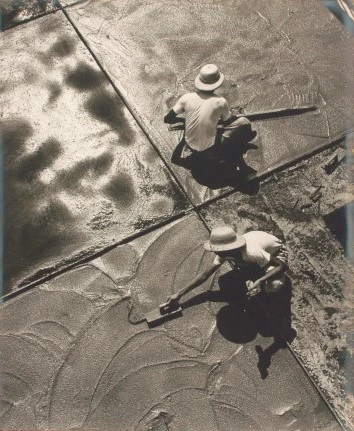

The Long Shadow, c. 1960s

Gelatin silver print

38.5 x 46.5 cm

Gift of the artist and his family.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

Image courtesy of Wu Peng Seng family

Wu Peng Seng (1915–2006) is among Singapore’s foremost photographers, noted for his landscape photography. Wu was born in Shantou, China and studied in Pui Ying College in Hong Kong before attending Guanghua University in Shanghai. His tertiary studies were interrupted by World War II and he moved to Vietnam in 1946, then to Penang two years later. In 1954, Wu arrived in Singapore and decided to settle here.

Wu was likely influenced by his father, a Qing dynasty official who was interested in photography. He taught himself photography before the war by reading books on the subject and attending exhibitions. As a result, he was able to take on a job as a photographer for a small Chinese language tabloid when he arrived in Singapore. When the newspaper subsequently folded, he went on to work as a salesman for photographic materials and later, for pens. [1] Yet Wu continued with his personal photographic practice throughout his life and remained an active and prominent member of Singapore’s photographic scene.

Wu had participated in photographic exhibitions in Singapore prior to his arrival. In 1950, when living in Penang, he submitted three photographs for the First Open Photographic Exhibition held by the Singapore Art Society at the British Council; one work, Evening Fishing, won the Silver Medal in the Landscape Category. He joined the Photographic Society of Singapore (PSS) after moving to Singapore. He quickly became an active member – he did not merely participate in its excursions and exhibitions, he also helped fellow members submit their photographs to international salons, acted as a jury member for salons, was a council member for the PSS and the Chinese editor for the club’s monthly bulletin.

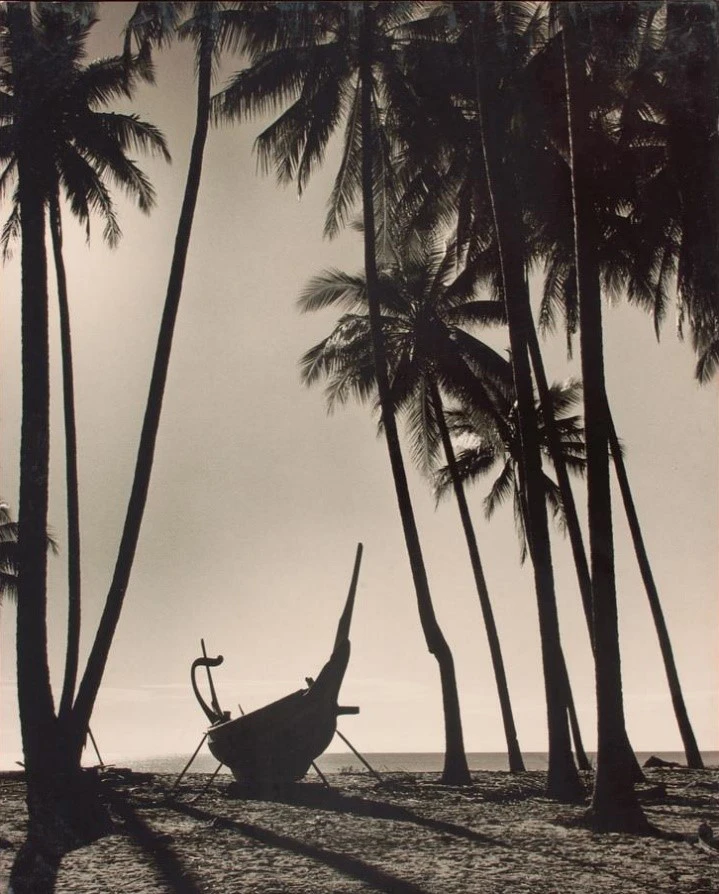

When looking at pictorial photographs from post-war Singapore, most attention is paid to images of kampongs, fishermen, labourers and street scenes that appear to offer an insight into daily life at the time. Recent interpretation of Wu’s works has therefore emphasised their evidential qualities rather than aesthetic achievements. For example, an article in Lianhe Zaobao (1996) described Wu’s photographs as showing “the idyllic country life of bygone days, featuring scenes such as geese swimming leisurely in a pond, coconut trees swaying in the breeze, fishermen casting their nets in the hope of a good catch, or a kampong maiden going about her daily chores.”[2] Another article in The Straits Times (2008) described the scenes as “everyday life from the 1940s and 1950s.”[3]

Certainly, works like At Rest (1964) and Her Daily Work (c. 1950s) lend themselves to such readings, however pictorial photographers like Wu never sought to make documentary records. Instead, their preference was for expressive, aesthetic images that prioritised technical excellence and craft. This can clearly be seen in works such as The Long Shadow (c. 1960s) and First Step (c. 1960s). Both are technical exercises involving a model ballerina and demonstrate Wu’s personal style of using geometric lines to create striking compositions. Wu was particularly fond of shooting from a high vantage point and using diagonal floor lines to create depth. Other examples include Two Cement Workers (c. 1959) and Covering with Cement (1959).[4]

When we view The Long Shadow alongside Two Cement Workers and Covering with Cement, it becomes apparent that, rather than trying to represent life in Singapore, Wu was constructing stylised photographs that played with form, tone and line. In viewing these photographs, could we consider them as a precursor to the developments in abstraction championed by the Modern Art Society in the 1960s, instead of associating them with realism or documentary photography? The human figures in his photographs were never meant to be individuals; they are simply part of the “pattern” that he was creating, a point of interest in the composition.

Photography’s close relationship with realism due to the medium’s indexical capabilities has influenced interpretation of pictorial photography in Singapore, leading to a dominance of “the real” in the reception of such work. This is partly due to photography’s absence from most art historical narratives in Singapore. In bringing these photographs into such narratives, one can begin to gain a richer understanding of the circumstances of their production and circulation. Wu’s photographs, created and shown within the camera club circuit, were always made within the context of “art” and assessed using aesthetic criteria. In shifting our appreciation of his work from the evidential to the aesthetic, one might not only gain a more complete picture of art history in Singapore, but also appreciate the complex way photography is able to slide between the opposing ends of index and icon.

Notes

- Seah, L., “He scales 600-m high mountains to shoot scenery,” The Straits Times, January 24, 1997, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- “美的旅程 [Mei de Lu Cheng],” ;联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], October 19, 1996, p. 48. English translation of description taken from http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2014-01-16_160401.html, accessed 6 October 2017.

- “Seeing Beauty in Everyday Life,” The Straits Times, April 17, 2008, p. 47.

- Two Cement Workers is currently on display in DBS Singapore Gallery 1. The work will be replaced with The First Step and Long Shadow ;in June 2020. Read more on artwork rotations here: https://www.nationalgallery.sg/magazine/the-ever-changing-uob-southeast-asia-gallery.