Nhek Dim’s Village Scene: History, Tropical Abundance, and Tragedy

On first appearances, Village Scene is a lively and cheerful depiction of rural life. Yet, this harmonious-looking work is also a poignant reminder of a tumultuous time in Southeast Asia that ultimately led to a period of unimaginable tragedy in Cambodia. Roger Nelson looks into the painting's subject matter, style, and exhibition and publishing history to explore how it intersects with the Cold War and related conflicts.

Village Scene, 1960

Oil on canvas, 55 x 75.5cm

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Made in 1960, Village Scene by Nhek Dim (b. 1934, Cambodia; d. 1978, Cambodia) is a cheerful-looking painting, evoking a profound sense of tropical abundance. The artwork typifies the sentimental style of Nhek Dim, who was Cambodia’s most prominent visual artist during the period, and remains among the best-known in the country today. Yet behind its seductively harmonious appearance, the painting’s history also points to its relationship with the politics and violence of the global Cold War, as well as the escalating conflict in Vietnam during the Second Indochina War. In addition to being a lively and happy depiction of rural life, Nhek Dim’s Village Scene is a poignant reminder of a tumultuous time in Southeast Asia, which ultimately led to a period of unimaginable tragedy in Cambodia.

This short article will first examine the painting’s subject matter and style, taking into consideration the context in which it was made. It will also look at where the painting was exhibited and published, and where it eventually ended up. These aspects of the artwork’s history reveal its intersections with the Cold War and related conflicts.

Looking at Village Scene

Anyone who has spent time in a small Cambodian village may be familiar with elements of the scene depicted by Nhek Dim in this artwork. Although the artist has idealised his portrayal to convey a sense of idyllic rural harmony and plenty, he has also drawn on recognisably real aspects of rural life.

The image depicts a woman applies finishing touches to a type of clay pot commonly used for cooking and carrying water, known in Khmer as a chhnang. Several other already completed pots sit by her side. A second woman looks on, with a child in her arms and another by her side; she is dressed in a sarong which hugs her youthful figure. Two men prepare food, their bare chests bound by the strong muscles that come from working the land; meanwhile, in the background, a sturdy buffalo pulls a cart laden with rice. The figures are surrounded by banana palms and other lush foliage, reminding us of the fertility of the tropical environment while framing the scene in a manner that is picturesque and appealing. Sunlight falls in dappled patches on an open clearing behind the figures, and the sky above is bright and blue.

All these elements in the painting emphasise the abundance of the Cambodian countryside. This was a recurring concern for Nhek Dim, dominating most of his known surviving paintings. Views of rice fields, often dotted with sugar palms or being harvested by Khmer peasants, are especially common in the artist’s oeuvre. While depictions of community life in a village setting are less common in Nhek Dim’s paintings, Village Scene shares with more typical works such as La Moisson (The Harvest, 1961) an emphasis on the productivity of the countryside. Rice fields generate an agricultural bounty, while in villages, people process the rice harvested from these nearby fields, as well as producing pottery, preparing foodstuffs, growing fruits, and so on.

Looking around Village Scene

This recurrent focus on rural productivity in Nhek Dim’s work, including in Village Scene, may be best understood in the context of the agriculture-centric policies propounded by Cambodia’s principal political ruler and Head of State during the 1960s, the prince and former king, Norodom Sihanouk (b. 1922, Cambodia; d. 2012, China). Sihanouk’s policy of “Khmer Buddhist Socialism” was essentially a new way of articulating a longstanding economic and social reliance on the cultivation of rice. This and related programmes promoted in this period were described in a Khmer novel by Suon Sorin, titled A New Sun Rises Over the Old Land that was first published in 1961, a year after Nhek Dim’s Village Scene was made. Sorin wrote that Sihanouk’s policies “elevated the status of the peasants, to be valued citizens in the national society.” At Sihanouk’s direction, “every government officer must throw down his pen, once in a while, in order to take up a hoe, a spade, a scythe, and farm alongside the common people. This is in order to teach them to understand in their hearts and in their minds about the lives of the common people.”

It is known that Nhek Dim was close to Sihanouk: the Head of State collected the artist’s work, and one of his paintings even appeared in a feature film that Sihanouk directed. It is also known that other artists active in Cambodia during this the period also often concentrated on rural subject matter in their artworks. One important example is Sam Yoeun (b. 1933, Cambodia; d. circa 1970, Cambodia), whose prints from the 1960s are currently on display in UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 6, in the same room as Village Scene. Sam Yoeun’s prints portray rice farming, women carrying pots, and related scenes of countryside life. Hence, Nhek Dim’s emphasis on the fertility of the countryside comes as no surprise, and reflects the political setting in which the painting was made, during the first decade following national independence from colonial rule.

The style of the painting, like its subject matter, also reflects its context. Representational paintings that depict scenes from daily life, like Village Scene, were a new and distinctly modern phenomenon in the Cambodian setting at the time this work was made. Prior to the late 1940s, representational painting was largely forbidden at the School of Cambodian Arts (École des Arts Cambodgiens) in Phnom Penh, and students were not taught how to draw or paint scenes from life. When this policy was eventually changed at the School, it led to a dramatic rise in the popularity of representational paintings during the 1950s and 1960s. This shift also corresponded with the emergence of the first modern buildings designed by formally trained Cambodian artists, the first movies made by Cambodian filmmakers, and an expanding interest in Khmer novels written by Cambodian authors, which had first emerged in the vernacular language only two decades prior.

Representational paintings by Cambodian artists were described in Khmer at that time as gamnur samay or “modern paintings,” and practitioners of this exciting and distinctly modern form were known as vicitrakar, a neologism which referred specifically to Cambodian representational painters. The use of these terms reflects the modern cachet attached to representational paintings in the Cambodian context. By contrast, representational painting was actually being rejected in other Southeast Asian settings during this period—our recent article on Constancio Bernardo (b. 1913, Philippines; d. 2003, Philippines) describes the debate between representational painting and abstraction that was taking place in the Philippines from the 1950s onwards. In the Philippines, however, these techniques had been taught to local artists since the early 19th century, more than a century prior to the introduction of gamnur samay in the curriculum at Phnom Penh’s School of Cambodian Arts.

The warm colours and flattened forms in Village Scene are typical of Nhek Dim’s approach to representational painting. The artist worked as a designer for the American Embassy in Phnom Penh, and in 1957 he spent six months in Manila studying printmaking and publishing techniques with the support of the United States government. A number of advertising and tourism posters designed by Nhek Dim survive, in which similarly vibrant tones recur. In 1963, the artist would travel to the USA and spend more than three years there studying under the celebrated American animator, Walt Disney. Nhek Dim’s simplified approach to form and his sentimental approach to colour reflects these experiences, while his use of light impasto for his expressively visible brushstrokes in Village Scene conveys the enthusiasm with which this vicitrakar adapted the techniques of gamnur samay to evoke the look and feel of the tropical, rural environment.

Exhibiting and publishing Village Scene

We have seen that Nhek Dim enjoyed the patronage and support of both Norodom Sihanouk and the United States of America through various organisations including the American Embassy in Phnom Penh, as well as the US Information Service.

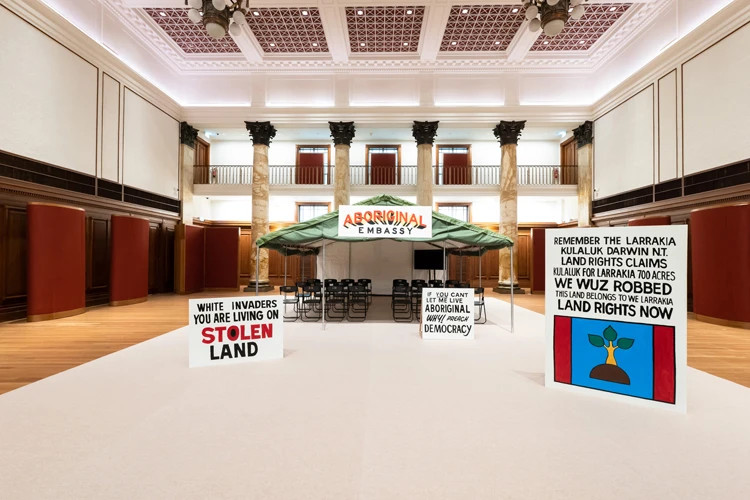

Village Scene was prominently displayed in a major exhibition organised by the US Information Service in 1961. Its image was subsequently reproduced in an American-made magazine called Free World, for distribution across Southeast Asia and internationally, as well as in a calendar distributed throughout Cambodia. This means that Village Scene would have been among the most nationally, regionally and internationally prominent of all Nhek Dim’s artworks at the time it was made. Tracing the history of this exhibition and these publications, as well as the artwork’s subsequent fate in the decades to follow, offers a fascinating insight into the painting’s entanglements with the tumult of the Cold War period.

That both the Cambodian Head of State and a foreign superpower actively championed Nhek Dim reflects the political climate in which he worked. For Sihanouk, promoting the arts and culture were central to the articulation of a Cambodian national identity in the decades following national independence from colonial rule, which had been achieved in 1953. This was a strategy adopted, in varying ways, by many of the leaders of newly decolonised Southeast Asian nations; several of Sihanouk’s peers in neighbouring countries also established important collections of modern art, and supported the arts in other ways as well. The Khmer novelist Suon Sorin asserted in his 1961 novel A New Sun Rises Over the Old Land that “under the brilliant and clear leadership of His Majesty Norodom Sihanouk, Cambodia had taken a very large step toward a new era, ‘the era of building.’” It was in this “era of building” that Nhek Dim was working, and we may imagine that it is this era that is depicted in Village Scene.

At the same time that Cambodian artists and political leaders were striving to articulate the nation’s identity in the wake of decolonisation, foreign powers were also vying for influence and control. Cambodia was officially neutral or non-aligned in the Cold War struggle during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Additionally, the nation neighbours Vietnam, where the Second Indochina War was escalating rapidly at the time. These two factors made Cambodia a key strategic battleground, with the USA investing heavily in cultural diplomacy during these years in an attempt to prevent the nation siding with the communist bloc.

Exhibitions of artworks by artists living and working in Cambodia were a key part of American cultural diplomacy efforts. From 1960 to 1962, the USA organised large annual exhibitions in Phnom Penh, showing paintings by dozens of artists. The number of participating artists increased with each edition, and the number of Cambodians visiting was also reportedly very large. Photographs showing bicycles parked outside the exhibition venue indicate the size of the crowd, and also suggest that it included large numbers of students and ordinary citizens, who travelled by bicycle, in addition to the wealthier elite who would have travelled by car.

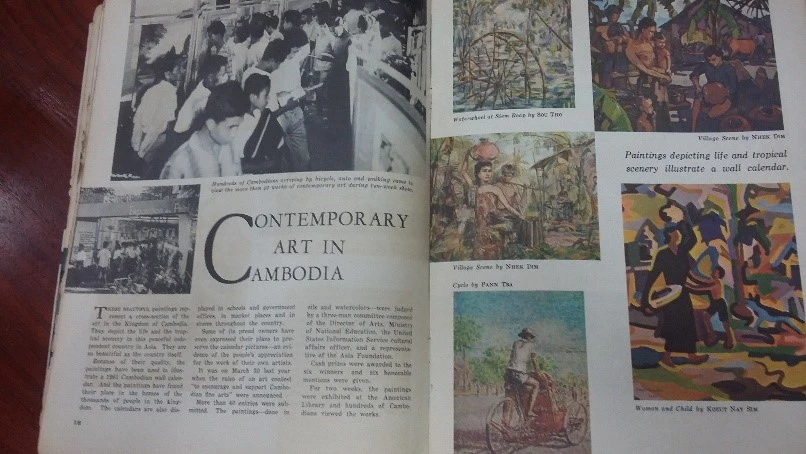

Nhek Dim’s Village Scene would have enjoyed an even larger audience in Cambodia, due to the artwork having been reproduced on a wall calendar that was printed by the US and distributed throughout the country. This large domestic audience was soon joined by a regional and international audience, as the painting was again reproduced in Free World magazine, published by the US in various Southeast Asian languages and circulated widely as part of America’s cultural diplomacy programme in this period. A view of the double-page spread in which Nhek Dim’s artwork was featured indicates that Village Scene was one of several paintings with rural subject matter, captured in a representational painting style that favoured warm colours, blue skies, and a generally cheerful and optimistic mood.

Searching for Village Scene

Likely as a result of the painting’s prominence, it probably caught the eye of an American soldier, who most likely purchased the painting, brought it back to the United States, and then abandoned it. For years, the painting disappeared. What happened to Village Scene in the decades following its exhibition and publication in 1961 is somewhat uncertain, but we can speculate with some confidence about these events. We know that the painting was found inside a cupboard in a mobile home in rural America, in the late 2010s. We also know that this mobile home had previously been owned by an American soldier who had served in the Second Indochina War.

While it may seem sad that the painting seems to have been lost and forgotten for decades before it was acquired by National Gallery Singapore in 2019, on the other hand, we may also be grateful that it survived the devastation that ravaged Cambodia in this period. Having been officially non-aligned when Village Scene was painted in 1960, Cambodia became increasingly involved in the Second Indochina War as the 1960s progressed. In 1970, civil war broke out and Sihanouk was overthrown, replaced by a new US-backed regime. Nhek Dim continued to paint prolifically in this period, but this was forcibly stopped in 1975 when the nation was thrown into unimaginable turmoil, as Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge troops took power of the nation, and banned most forms of modern art and culture. Nhek Dim was one of an estimated two million Cambodians who perished during the Khmer Rouge regime, which terrorised the country from 1975 until 1979. The writer Soth Polin (b. 1943, Cambodia) describes this period as “something that we cannot get past. It just kills the imagination.”

Village Scene is one of around 200 paintings by Nhek Dim known to have survived this period of violence, in which artists were deliberately targeted and killed, with many artworks lost or destroyed. Its cheerful depiction of a rural community that appears close-knit and prosperous takes on a special poignancy in light of the painting’s chequered history in the ensuing decades, and artist’s tragic fate.

Today, the countryside in Cambodia and many other parts of Southeast Asia is again being invoked by political leaders who watch as massive hydroelectric dams change the ecosystems of rivers and floodplains, as climate change makes it impossible to rely on once dependable weather patterns and fishing sources, and as deforestation transforms once-abundant tropical environments into wastelands.

To be sure, Nhek Dim idealised the rural environment he depicted in 1960 in Village Scene. But what might a “village scene” look like today, or in the future? Might Lim Sokchanlina’s (b. 1987, Cambodia) photographs documenting rural houses sawn in half to accommodate the expansion of a major highway offer some clues? Or Vandy Rattana’s (b. 1980, Cambodia) depictions of “bomb ponds”—craters formed by American bombing—which may still be found among the rice fields in the Cambodian countryside? Nhek Dim’s work will continue to provide a source of insight and inspiration for artists of this generation, and generations to follow.

This article draws extensively on: Roger Nelson, “‘The Work the Nation Depends On’: Landscapes and Women in the Paintings of Nhek Dim,” in Ambitious Alignments: New Histories of Southeast Asian Art, 1945-1990. Edited by Stephen H. Whiteman, Sarena Abdullah, Yvonne Low, and Phoebe Scott, 19–48. Sydney and Singapore: Power Publications and National Gallery Singapore, 2018.

References and Further Readings

For further reading on art in Cambodia during Nhek Dim’s time, see: Ingrid Muan, “Citing Angkor: The ‘Cambodian Arts’ in the Age of Restoration, 1918–2000.” PhD Diss., Columbia University, 2001.

On Khmer literature, see: Suon Sorin, A New Sun Rises Over the Old Land: A Novel of Sihanouk’s Cambodia. Translated and with an introduction by Roger Nelson. Singapore: NUS Press, 2019.

Editor’s note

See Nhek Dim’s Village Scene in person at the Gallery. The painting is currently on display in UOB Southeast Asia Gallery 6 (Supreme Court Wing, Level 3), and was installed recently in November 2020 as part of the Gallery’s regular updates to our long-term exhibitions.