Sam Yoeun’s Etchings from the 1960s

Although little known today, Sam Yoeun was one of the most prominent artists in Cambodia during the 1960s. A recent acquisition of his artworks now on display in the UOB Southeast Asia Gallery sheds new light on this fascinating figure.

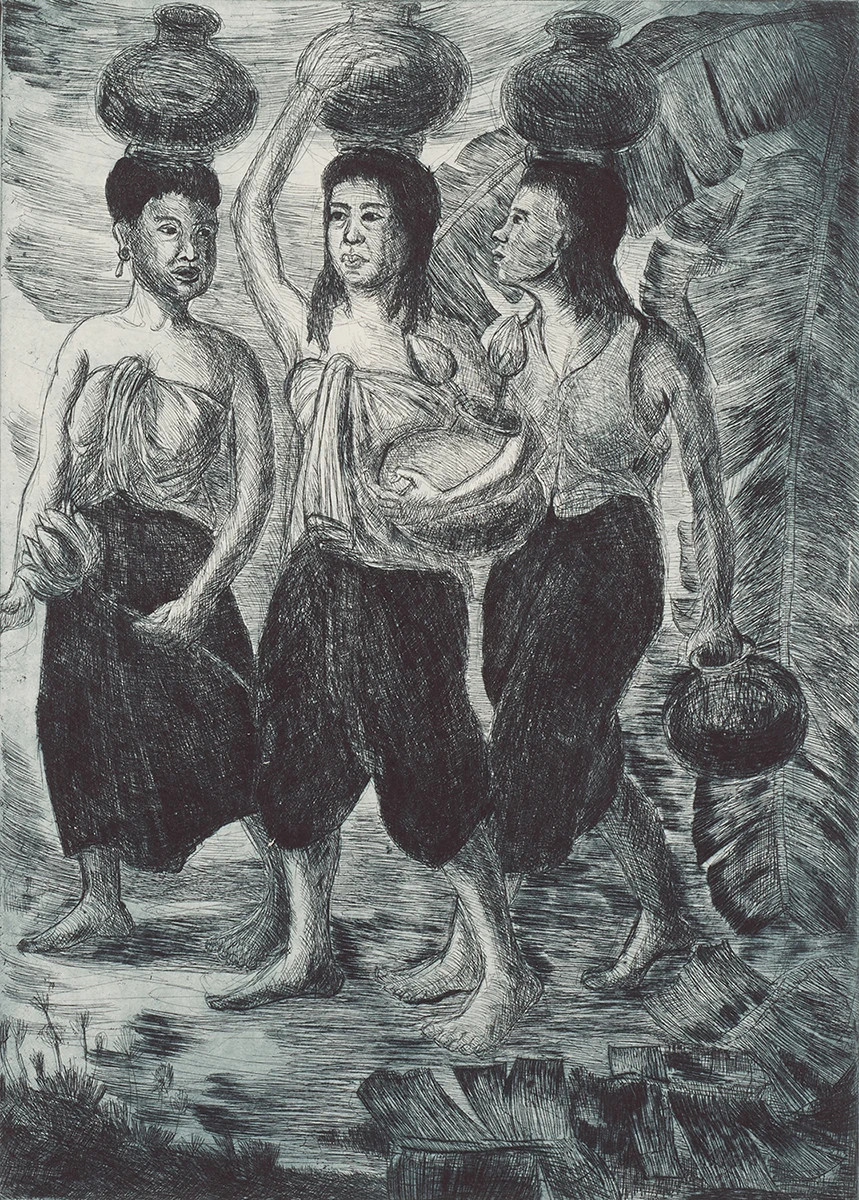

Etching on paper. 29.0 x 40.8 cm. Gift of Dr Maria Heiner, Dresden, Germany.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore. Image courtesy of National Heritage Board.

Although little known today, Sam Yoeun (b. 1933, Cambodia; d. c.1970, Cambodia) was one of the most prominent artists in Cambodia during the 1960s. A recent acquisition of his artworks now on display in the UOB Southeast Asia Gallery sheds new light on this fascinating figure.

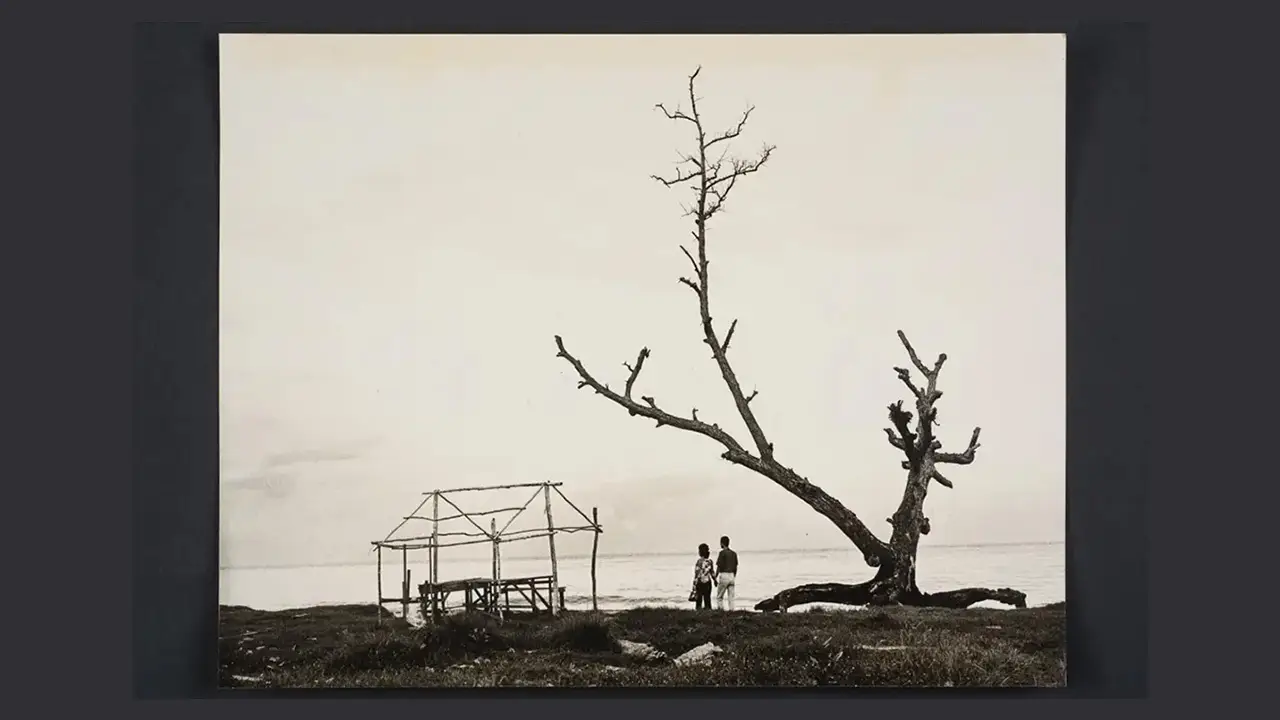

In July 1968, a photograph published in the Cambodian magazine Réalités Cambodgiennes depicted the “lovely façade” of Sam Yoeun’s Phnom Penh gallery. This is one of the only surviving images to record the appearance of one of the many exhibition spaces that flourished in Cambodia during the 1960s. The photograph shows the gallery window emblazoned with the Khmer word, vicitrakar. At that time, this newly-coined term was used to refer specifically to representational painters, who were regarded as exciting and modern. The word has since come to have a much broader meaning, referring to modern or contemporary “Cambodian artists” working across most visual media.

Just visible in the 1968 photograph and described in an accompanying review, Sam Yoeun’s gallery mostly displayed artworks depicting Cambodian landscapes. Writing of the exhibited paintings and prints, the reviewer notes that “alongside the traditional ‘figurative,’” the interested public could also see “Cambodian landscapes in a much less conventional way”.

A series of nine etchings by Sam Yoeun, recently acquired by National Gallery Singapore as part of a generous gift from Dr Maria Heiner of Dresden, Germany, are among the only surviving examples of the kinds of artwork exhibited in this gallery. They were probably considered “less conventional” because of their emphasis on depicting collectivity and labour, which is consistent with Sam Yoeun’s affiliation with communist organisations during the 1960s. He headed the Samagam Silpa Vicitrakar Khmaer (Association of Modern Khmer Painters), which was Cambodia’s only independent and oppositional artists’ association at the time. He also organised for artworks by its members to be exhibited in then-communist East Germany, where they remained until their recent donation to National Gallery Singapore.

Three of Sam Yoeun’s etchings have recently been put on display in the UOB Southeast Asia Galleries, which is the first time they have been exhibited anywhere in Southeast Asia in half a century. These prints depict groups of people engaged in everyday activities in Cambodia. In one image, women carry water in clay pots called kaam. In another, men and women harvest rice, wearing dark garments and krama chequered scarves, which would later become the compulsory uniform for Cambodians after the Khmer Rouge radical communists took power during the 1970s. A third work depicts a group of vendors carrying pineapples and other snacks in their baskets.

Although these works might have seemed “much less conventional” than more romantic depictions of the landscape by other artists prominent in Cambodia at the time such as Nhek Dim (b. 1934, Cambodia; d. 1978, Cambodia), Sam Yoeun’s interest in scenes of everyday life and work was shared by many other artists of the period, from other locations across Southeast Asia. In some places, this left-leaning approach became known as “social realism”. Such unflinching portrayals of labour and collective solidarity marked a significant trend in visual arts including printmaking, and can also be found in Southeast Asian literature, cinema, and other media from the period.

While Sam Yoeun’s approach recalls that of many artists in other parts of Southeast Asia, there are aspects of his story, and that of modern art in Cambodia, which are tragic and unique. Under the Khmer Rouge regime of the late 1970s, artists were deliberately targeted as part of a genocide that saw the deaths of around two million people. According to Chheng Phon, a choreographer and researcher, between 80 and 90 per cent of artists and intellectuals in Cambodia were killed or exiled. Describing the unimaginable horror of the Khmer Rouge period, in 1983 Phon wrote that “the summits of wisdom and creative genius… reached zero in the genocidal regime. All artists, all poets suffered greatly, terribly despondent at the evil misfortune that had befallen the nation’s cultural foundations.”

Many artworks and documents relating to modern art were lost, dispersed, or destroyed during this period of devastation in Cambodia. The recent rediscovery of Sam Yoeun’s artworks in a collection in the former East Germany suggests that exploring transnational networks within the former communist bloc may be a rich site for further research. This will assist the ongoing process of reconstructing the history of modern art in Cambodia, and its place in the history of modern art in Southeast Asia.