Ask a Conservator | Frequently Asked Questions with Mar Cusso

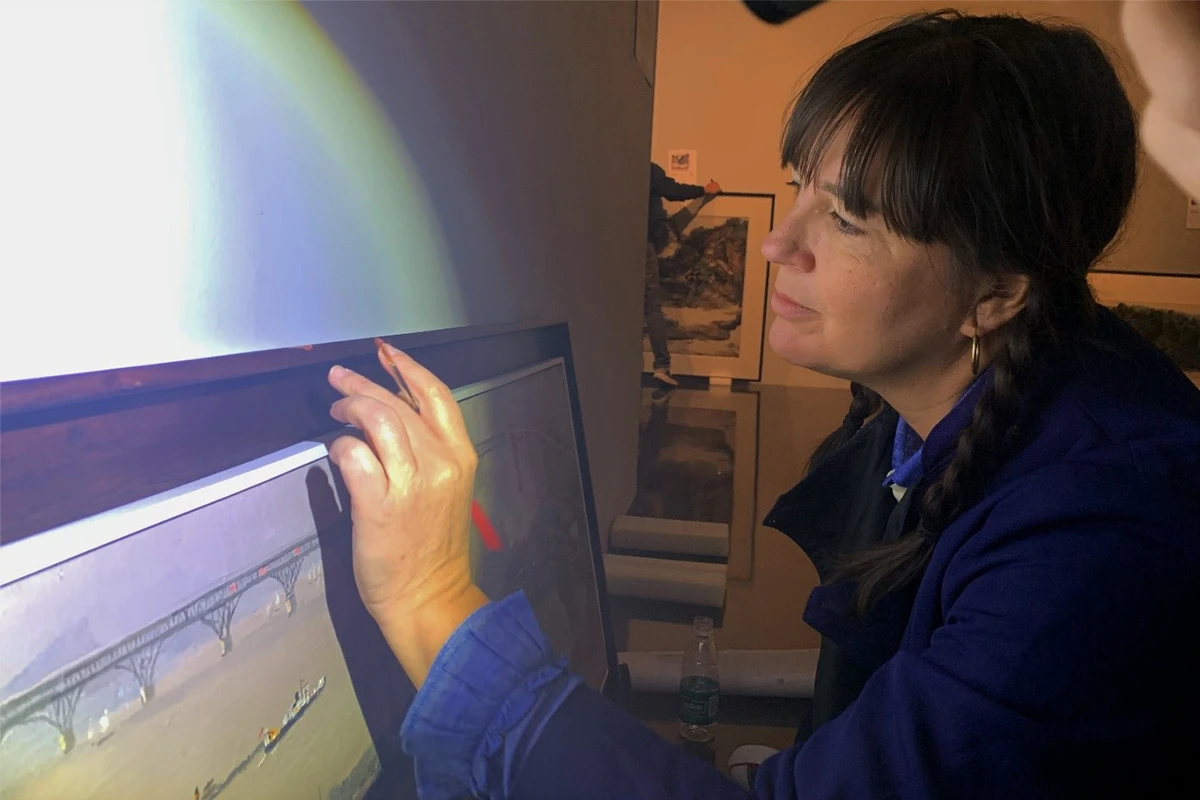

What does a conservator do every day? How do you assess the condition of a painting? Questions on conservation are some of the most frequently asked at the Gallery. Mar Cusso, one of the Gallery’s Paintings Conservators, answers them.

Questions about conservation are amongst the most frequently asked here at the Gallery, coming from everyone—first-time visitors, docents with years of guiding experience and front-of-house staff. Here to answer them is Mar Cusso, one of the Gallery’s Paintings Conservators.

Mar has 20 years of experience in painting conservation. She is based at the Heritage Conservation Centre, a state-of-the-art, purpose-built repository and conservation facility for Singapore’s National Collection. There, she cares for paintings in storage, and also conducts regular maintenance and routine condition checks on paintings on display at the Gallery. Alongside other conservators at the Heritage Conservation Centre, she ensures the preservation of these works for future generations.

How would you describe a typical day of work?

My work takes place mostly at the Heritage Conservation Centre, where the National Collection is stored and the conservation labs are located. In the lab, we have paintings undergoing different types of treatment. One of the first things I do when I receive a painting is document its condition. This is like writing a medical file for a patient, except in this case, my patient is a painting. We need to keep good and accurate documentation of the painting throughout the process, from its arrival to overall treatment.

To photograph and examine the painting’s condition in detail, we use different types of light waves. For example, ultraviolet light is used to examine any layer of varnish or coating to document any distortion. Racking lights are used to examine and document any distortions of the canvas' surface while infrared light is used to examine underlayers or underdrawings that the artist might have used for composition sketching before they added the paint medium.

Another exciting and important part of my job is to study the materials and techniques used by the artist. We use microscopes and scientific equipment to do so. We also collaborate with the Singapore General Hospital to perform X-rays on some paintings. The X-ray technique can provide valuable information on the layers underneath the paint, not visible to the naked eye.

I also conduct practical treatments on the paintings. These can include cleaning of the paint layer, removal of oxidised and yellowed varnish layers, retouching any areas of loss and consolidation of any active flaking paint. This can often be time-consuming, but it is the part of my job that I enjoy most. During treatment you end up creating a dialogue with the artwork tthrough understanding its materials and the artist's intention.

How do you assess the condition of the paintings prior to their storage at the Heritage Conservation Centre?

Conservation is an interdisciplinary science that requires close collaboration with professionals from other fields. For example, we often meet with curators to learn about the artists’ intention of their artworks and the choice of material.

The conservators follow a strong code of ethics and standards based on the minimal intervention approach and maximum respect to the original artists’ intention. As every painting is unique, each treatment is tailored to its specific need. That is why we spend a lot of time researching and understanding the behaviour of the materials used by the artists.

What is the criteria for a painting to be sent for conservation or storage?

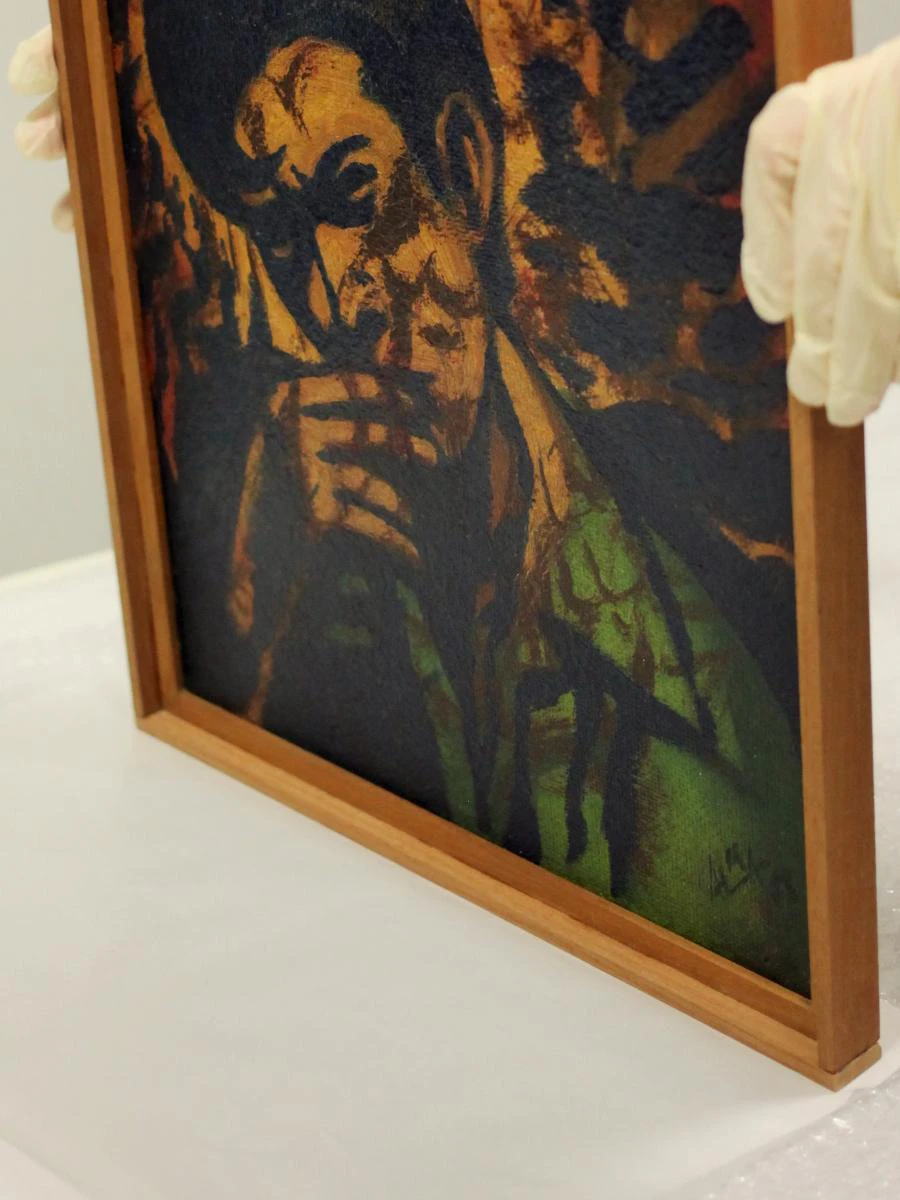

Paintings that are brought to the conservation lab generally have requirements for special treatment. They have either been selected for display at the Gallery or may be sent overseas as part of a special changing exhibition or travelling show. We also acquire paintings into the National Collection that might require immediate treatment. If a painting displays any type of instability, it will be brought up to the lab for treatment or stabilisation. One example would be a painting with active flaking in its paint layer. In this case, we would consolidate the surface to avoid further loss of paint.

I would categorise a conservator's work through two main types of intervention: structural and aesthetic. Structural interventions are used for unstable paint layers, distortions and undulations, which in the long term, can cause damage to the paint layer. Aesthetic interventions are used for oxidised and yellowed varnish layers or losses on paint layers that may require retouching, or when revisiting previous conservation treatments done in the past that may now require a new or updated approach.

I would also like to highlight that conservation is a constantly evolving science. It is very important to stay updated on the latest trends and developments in the fields of conservation research and technologies. Attending conferences and seminars are examples of useful platforms that enable the conservation community to discuss the latest scientific and technological updates.

Do all artworks undergo treatment before they enter storage?

We usually carry out an assessment as part of the pre-acquisition process. This exercise can be done either by viewing the potential acquisition pieces together with the curator in person, or photo documentation of the works if it’s not possible to be on-site. Based on this information, we write a pre-acquisition condition report to highlight any issues, including factors such as the use of particular materials prone to deterioration. We also give an estimation of the hours of conservation work that the artwork will require.

Once the new acquisitions arrive at the Heritage Conservation Centre, we conduct a condition check where we assess if the painting is in good and stable condition to be stored. We also look out for pest and mould infestation as these require immediate intervention, such as quarantine. If we find any structural issues during this check, these paintings will be brought to the lab for treatment.

How do environmental factors such as light and relative humidity affect an artwork’s condition over time? Is there a minimum or maximum duration for an artwork’s display?

Unstable environmental conditions can cause irreversible damage to artworks. All the artworks and artefacts in the National Collection are kept in a controlled environment with specific temperature and relative humidity settings. The ideal relative humidity and temperature settings for artworks in storage and on display are generally 55% (+/- 5%) and 22 degrees (+/-2 degrees). We also bear in mind that every material responds differently, and it is for this reason that artefacts and artworks of varying mediums are stored in facilities with different environmental settings. For example, artefacts and artworks made of metal are stored in a relative humidity setting of 40-55%. We face a greater challenge with contemporary artworks of mixed media, as each constituent material behaves differently.

The duration of an artwork’s display depends on many different factors. One of the most significant is the lighting lux level. Lux is the unit used for illuminance. For oil- and acrylic-based paintings, the maximum lux level for display is 200 lux, and for paper and textiles it is generally lower, ranging from 30 to 50 lux. This is because some of the materials are extremely fragile and can fade under light exposure—damage that is irreversible. As a result, the display of paper-based artworks is limited to a specific period of time, calculated with a scientific rule to compute the resting period required before the work can be displayed again.

Will iconic artworks such as Chua Mia Tee’s National Language Class, Raden Saleh’s Forest Fire and Georgette Chen’s Self-Portrait ever be rotated out of the display? Do the same conservation requirements apply for these works?

Paintings can be displayed for a long period of time unless the medium is sensitive (e.g. gouache, tempera or batik). We carry out regular artwork checks on site where we assess the condition of the paintings on display. As these are very recognisable works of art, as long as they are in stable condition, they can remain on display. As for the conservation requirements, all the paintings in our National Collection are treated based on internationally agreed standards of minimal intervention and use of reversible materials.

Editor's Note

For more on conservators’ work, watch the Heritage Conservation Centre’s series Behind the Scenes. To explore the Gallery’s collection of art online, visit National Gallery Singapore’s Collections search portal.