Fernando Zóbel: The World of Abstraction, and the World Within

This essay by curator Clarissa Chikiamco explores the distinction between non-objective and abstract art through the practice of Philippine artist Fernando Zóbel.

Detail of image with permission from the Manila

Times and courtesy of Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation.

I

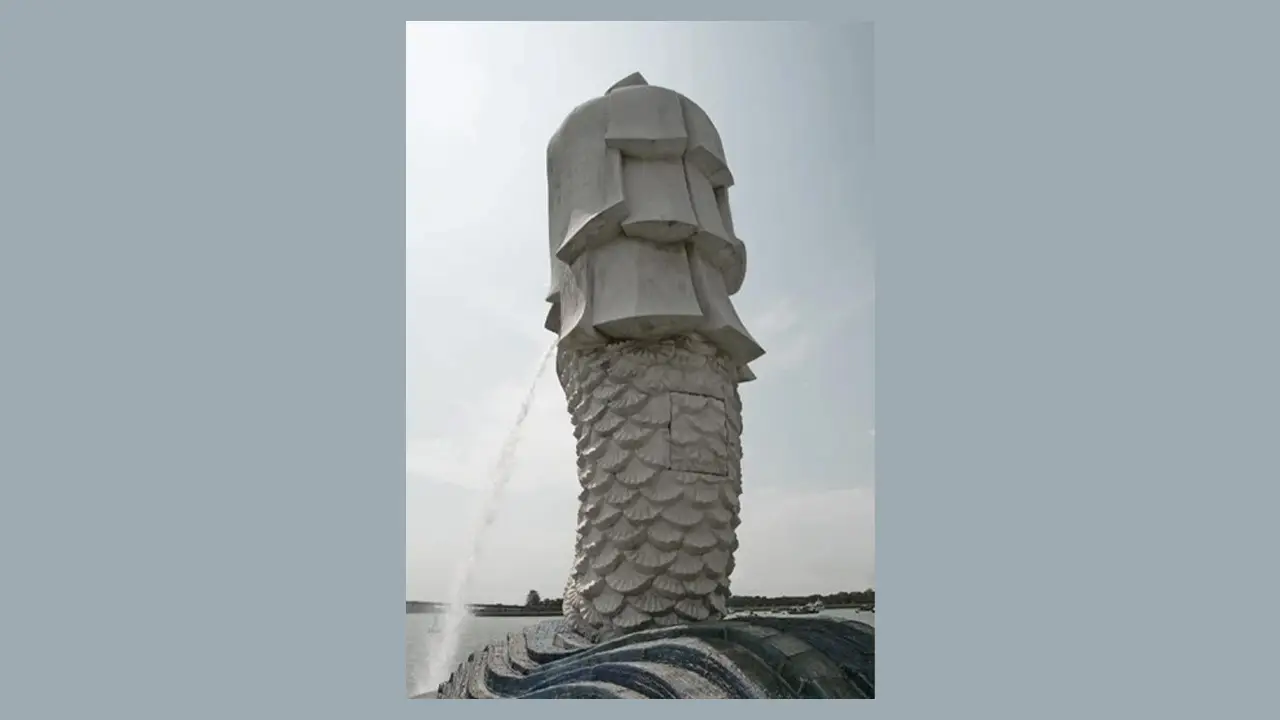

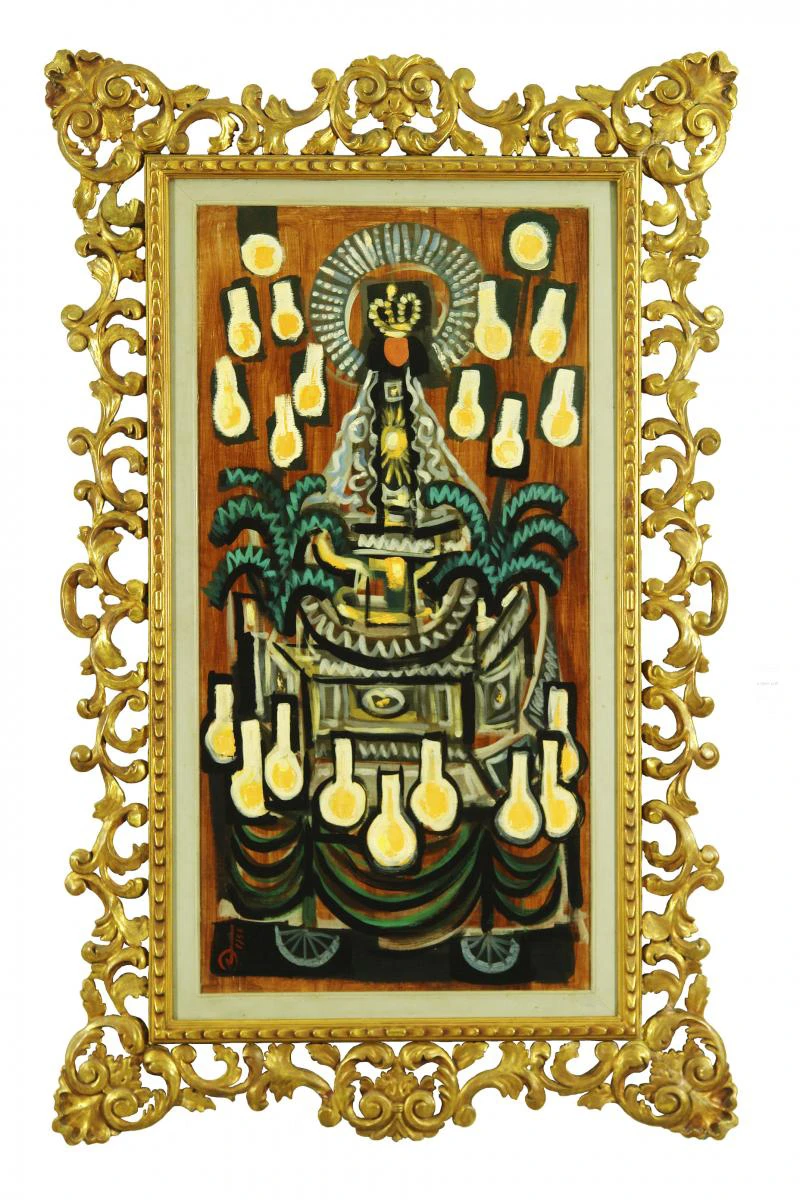

From an obsession with the individuality of existing objects that are so common to the country, they are no longer noticed, such as the design and decorations of the calesa lamp, the naïve magnificence of the elaborate carroza of local processions, and the peculiarly individual stance of the cigarette boy in Manila, Zóbel has swiftly moved farther and farther away from objective to non-objective painting.

-- entry on Fernando Zóbel in the Philippine Art Gallery catalogue of 19581

In 1957, under the auspices of the Art Association of the Philippines, Manila held the first exhibition-competition and conference of Southeast Asian art in the region. Aside from the international competition among the participating countries, the Philippines also had a local competition, divided into the categories of representational, abstract, non-objective, graphic arts, sculpture and photography. Among the fewest entries was the non-objective category, with only ten entries. The winning artists were Jess Ayco for Plutonian Passage (third prize), Emilio Lopez for Necrotomy (second prize), and Fernando Zóbel for Painting (first prize).2

That non-objective art was treated as an entirely separate category from abstract bears more investigation. Zóbel, its first prize winner, was a leading advocate of the non-objective, today understood as the same as abstraction or non-figurative art. Active in Manila during a time when art and artists were tensely pulled between the classifications of “modern” and “conservative,” Zóbel articulated his own artistic motivations as well as that of his peers who identified with the modern. Conflated with the non-objective, the labour of abstraction as manifested in the Philippines during the post-World War II period resonated with similar efforts in Southeast Asia. Yet it would be associated with such terms as “international” and “universal”, in tension with the burgeoning question of Southeast Asian national identities wrung from centuries of a colonial past, and the Cold War agendas intent to promulgate the language of abstraction.

II

A self-taught artist, Zóbel initially practiced with and received informal training from Boston-based artists Hyman Bloom, Reed Champion and Jim Pfeufer during his studies at Harvard University. After returning to his place of birth, Manila in 1951, Zóbel worked in his Spanish-Filipino family’s real estate business while practicing art in his free time. In Manila, he frequently exhibited with artists considered “modern” at the Philippine Art Gallery (PAG). While the “moderns” had diverse approaches to form, what they had in common was that their art was, at least in appearance, different from the prevailing idealised representations of women, landscapes and genre scenes. The latter was popularized by Fernando Amorsolo, an artist whom Zóbel’s own father patronised in the early 20th century, and whose followers came to be known as “conservatives”, as they hewed to the establishment.

Zóbel’s art in these early years partly took on Philippine form as inspiration, derived from observations in reality. His Carroza (1953), which won the gold prize in the modern category of the 1953 semi-annual competition of the Art Association of the Philippines, was an abstracted form of the ornately decorated float used for religious processions in the Catholic country. Even then, he was less preoccupied with capturing the essence of a subject than its form. The art critic Ricaredo Demetillo wrote on Zóbel’s art then:

The subject matter of Zóbel’s paintings generally are of a representational nature, even when he is at his most abstract. You somehow feel that he is concerned with purging the object of its surface features to reveal the form beneath, that he eschews the retinal impression to contemplate purely thingness and compositional relationship of objects.3

If form was primary, Zóbel, however, struggled with making art of a completely non-figurative idiom. Few artists in the Philippines had ventured into it at that time. In 1953, the same year that he won the prize for Carroza, he participated in the First Exhibition of Non-Objective Art in Tagala, also held in the PAG. The poet Aurelio Alvero, writing for the exhibition catalogue as Magtanggul Asa, considered two of Zóbel’s entries, Plaza and Snappers, as the most distinguished of the twenty-eight artworks by eleven artists.4

Alvero described the non-objective as thus, “In this new trend, the artist does away with the depicting of the external of the object. He goes into the internal which to him is definitely more valuable. He fragmentizes his subject and finally reassembles the fragments into a composition that completely eliminates cognizable representation.”5 Within this is obviously inscribed a debt to the Manila-based group of post-World War II “moderns”, specifically the Neo-Realists. Composed of six artists who frequently exhibited together at PAG, the Neo-Realists had their first exhibition in 1950 and associated themselves with a quote by Italian literary critic Francesco de Sanctis that “to create reality, an artist must first have the force to kill it. But instantly the fragments draw together again, in love with each other, seeking one another, coming together with desire, with the obscure presentiment of the new life to which they are destined.”6 Alvero actually attributed the early exponents of a non-objective art to two of the Neo-Realists, Victor Oteyza and Hernando R. Ocampo, who were also exhibiting artists in the First Exhibition of Non-Objective Art in Tagala.7

To Alvero, abstraction was considered distinct from the non-objective with the latter being at the extreme, the non-representational. Finding some similarity with how Hilla Rebay, the first curator of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (precursor to the Guggenheim Museum), considered abstraction, Alvero thought of abstraction as literally abstracting from reality, reducing something from the objective world into forms to a varying degree.8 For as long as an abstracted image in the artwork somehow retained recognition to an object in reality, it could be considered abstract but not non-objective. This is evident in some of the paintings which were put in the abstract category of the First Southeast Asia Conference and Competition of 1957. Available images include those of City by Arturo Luz, The Joyous Kingdom by David Medalla, Carousel by Manuel Rodriguez, and Fiesta by Hernando Ocampo.9 This shows the range by which the term “abstraction” was considered at that time. The term would then come to subsume the “non-objective” as more artists turned to non-figurative forms.

Zóbel included non-objective art in his lecture notes for Ateneo de Manila University, where he taught “Introduction to Contemporary Painting” for a brief period in the 1950s. Under the non-objective, he noted that a “painting need have no relation with the appearance of natural objects. It can deal either with emotions (organic school: abstract expressionism) or with constructions (geometric school).”10 Though Zóbel would be a judge in the AAP’s 1958 annual competition under similar categorisations as the Southeast Asia exhibition, Zóbel was said to have actually preferred the term “non-figurative” over “non-objective.”11 With the confusion and arbitrariness of terms and categorisation, however, it is no surprise that Zóbel eventually concluded, “The whole abstract versus figurative thing bores me; I find it beside the point."12 For Zóbel, it appears he actually saw little difference between modern painting and conservative painting, thus by implication the abstract and figurative. Both were for visual pleasure, but modern art, with its predisposition to abstraction, was even more so. He wrote,

Modern painting, like painting of every age, is meant to please the eye and only the eye. Its main difference from conservative painting is that it can afford to do this without any other pretenses. In the old days, a painting tried to please the eye, it also tried to bring in recollections, to go with the furniture and give a social boost to the owner. Modern painters have dropped most of these adjuncts.13

For Zóbel, it was a matter of course that the figure would altogether be eliminated. He preferred the uninterrupted visual aesthetic on a flat surface, unencumbered by the associations figuration complicated the picture with. Within the painting was a world in itself, independent of the objective world. Zóbel had also begun to practice photography, which he realised best fulfilled the needs of representation and even exhibited his photographs at the Philippine Art Gallery in 1956.14 With this aside, he could pursue painting for nothing but painting itself.

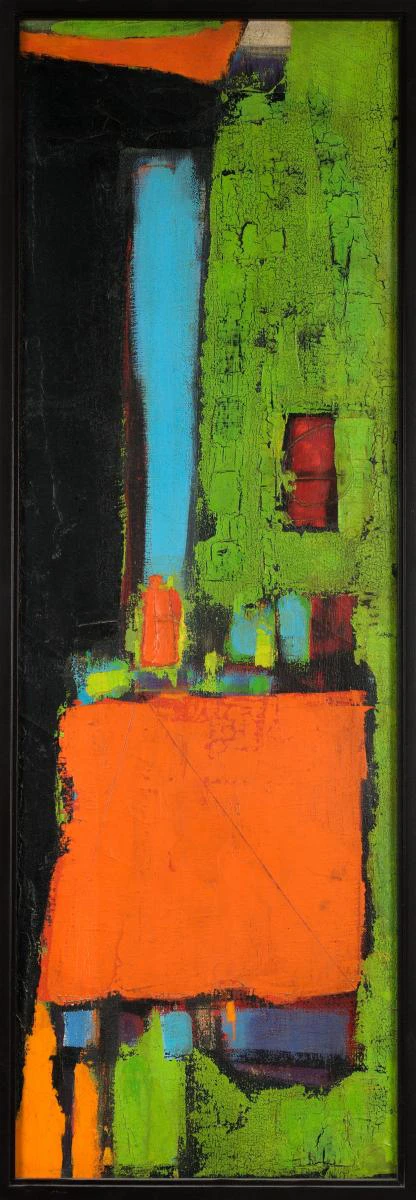

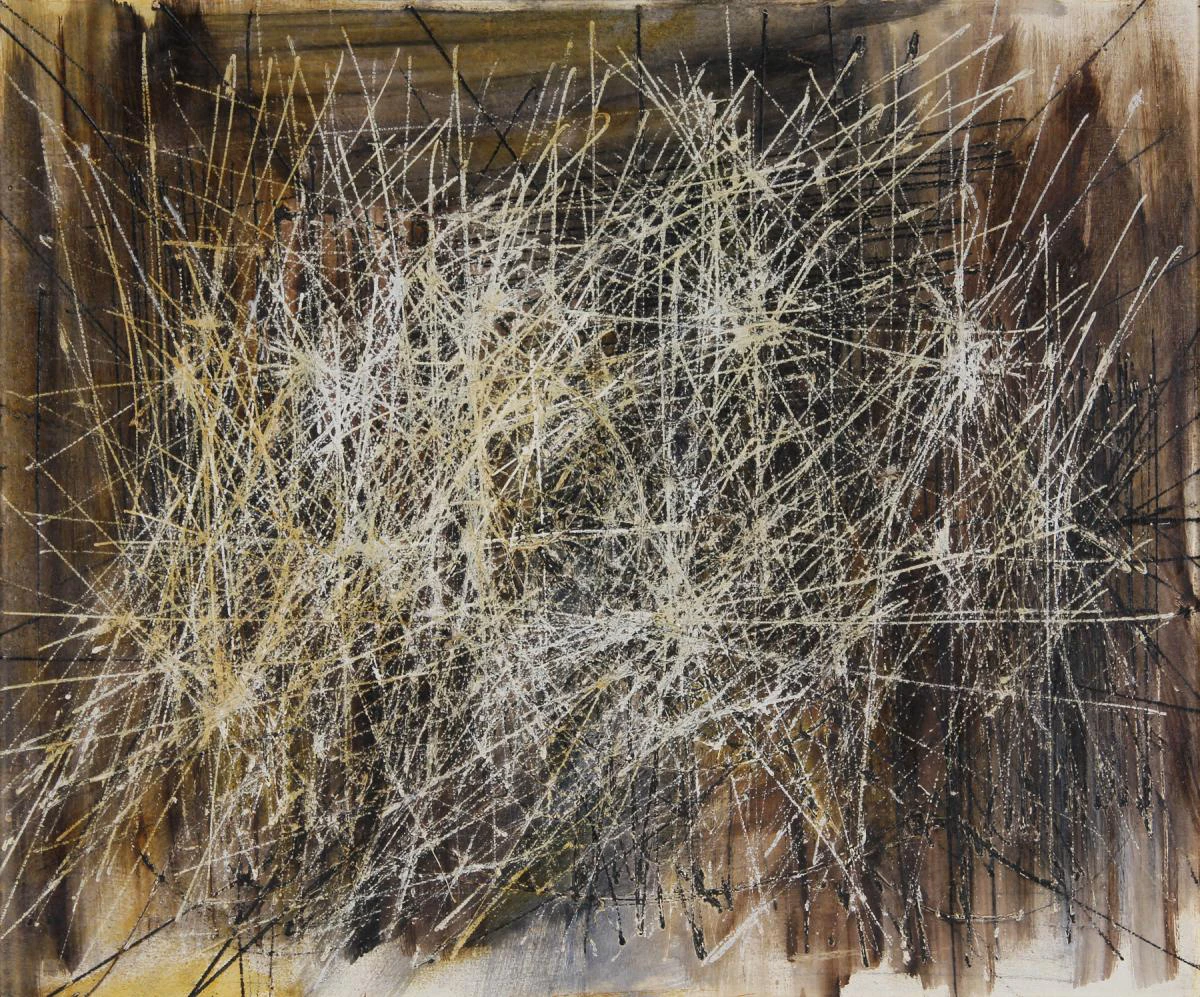

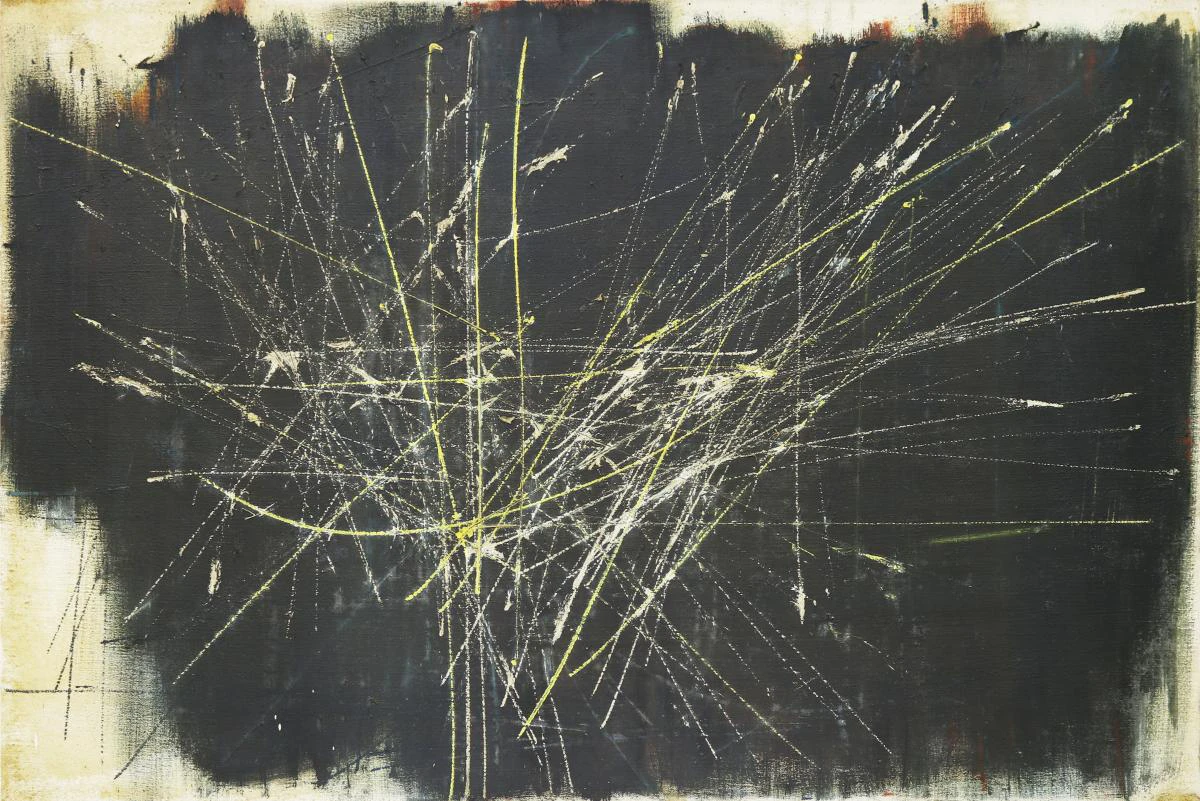

Wider appreciation of this purity of form in painting would, however, be difficult. Zóbel exhibited his Saeta series, paintings of lines administered via syringe-filled paint, at the PAG in 1957. He considered it his successful approach in abandoning representation, though the idea initially took flight from the lines of scaffolding he often saw while working for his family business. In reaction to the show, one writer asked, “THAT is art? All we saw were a bizarre collection of lines drawn and painted every which way, on vari[ous]-sized canvases.”15 A magazine featured Zóbel and his Saetas, and a member of the public wrote in that all he saw in this modern art were meaningless lines.16 When another Philippine artist, Lee Aguinaldo, Zóbel’s close friend and colleague, exhibited his Jackson Pollock-influenced paintings, it had likewise been dismissed as chicken scribbling.17 Abstraction was met with scepticism as people tended to look for the object, judge the work by its faithful representation to life, or to look for meaning in an artwork rather than only looking for visual pleasure. The works of modern artists were frequently trivialized as those which could be done by a child, as implied in one essay by Zóbel.18

Yet, Zóbel rebutted the idea that working on abstraction could be so simplistic. As recounted by the critic Demetillo: “Discussing [Jackson] Pollock’s technique of dripping paint on canvas, Zóbel said, in answer to an objection that such technique can be easily duplicated by a child at play: ‘Pollock’s art is totally calculated and craftsman-like; for he destroys as many canvases until he has achieved exactly the right effect. I have seen him do this.’”19 That Zóbel claimed to have witnessed Pollock in practice was likely an advantage he received by being a distant cousin of the New York-based Alfonso Ossorio, an accomplished artist in his own right and also Pollock’s patron.20 Zóbel worked in a way similar to the renowned Abstract Expressionist. His paintings were likewise calculated, produced only after numerous preparatory studies. He described preparation as taking several months to even as long as two years, destroying works he found unsatisfactory.21 Perhaps since being an artist was not widely considered a “proper” occupation in the Philippines at that time, Zóbel endeavored to approach his practice with discipline, neatness, and professionalism, countering it simply being hobby. His close artist friends Arturo Luz, Lee Aguinaldo, and Roberto Chabet had similar attitudes, being both erudite and methodical in their approach to art-making.

Acquisition made possible by Lam Soon Cannery Pte. Ltd.

III

It was upon seeing an exhibition of Mark Rothko, one of the American Abstract Expressionists, in 1955 that Zóbel realized abstraction’s potential.22 The exhibition, Recent Paintings by Mark Rothko, had been organized by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1954 and had travelled the following year to the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, where Zóbel was studying graphic techniques. Zóbel became convinced of abstraction’s possibilities, though he was far from alone as a foreign artist moved by this American movement. In parallel, Malaysian artist Syed Ahmad Jamal had seen a group exhibition of American Abstract Expressionism at the Tate during his stay in England.23 Jamal had noted its profound effect on him, the “main impact of Abstract Expressionism, [is] that of the emotive and mystical qualities, of the exteriorisations of the feelings and the sense, as a kind of direct form of mediation which telegraphs the intenseness of feelings[,] thought and imagination through plastic means.”24 Jamal would later be credited for making the first non-objective paintings of Malaysia with Umpan (The Bait) and Winter Wind in 1959.25

Umpan and Winter Wind were possibly a direct response to the Abstract Expressionism exhibition Jamal saw, which likely was either Modern Art in the United States or The New American Painting, shown at the Tate Britain in 1956 and 1959 respectively.26 The year before, The New American Painting went to Madrid where it left a deep impression on some of Zóbel’s Spanish contemporaries, artists from the abstract art group El Paso.27 Both shows were touring exhibitions by the Museum of Modern Art supported by the CIA-funded Congress for Cultural Freedom.28 Abstract Expressionism was covertly promulgated by the American government as it was associated with freedom of expression and the liberal values of democracy during the Cold War. Though not intended by its artists, their individual practices were grouped together, united as a cultural weapon against the more rigid Socialist Realism of the Soviet Union.29

The success and global reach of this American movement was traced by art historian Serge Guilbaut in transitions: “American art moved first from nationalism to internationalism and then from internationalism to universalism.”30 Before the war, American art was actually considered provincial and secondary to the art capital of Paris, hence the need to move away from previous conceptions of American painting. Veering away from notions of “national schools,” “internationalism” allowed the new movement of Abstract Expressionist art from America to be presented as worldly and avant-garde and moreover, to be claimed as universal—elevating their representation above the national to humanist ideals.31 The aggressive approach and widespread marketing, in part through touring exhibitions, magazines, scholarships, and exchanges with America, were effective. Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, principal founder of the Art Association of the Philippines, and Amadis Guerrero observed: “The effect of all this was to shift attention away from the school of Paris to the school of New York. Filipino artists who looked up to such masters as Picasso and Braque now began to acknowledge the leadership of their American counterparts.”32 Artists the world over started to recognise America as the new cultural superpower.

“International” and “universal” were two particular words embraced in discussing abstraction. In Southeast Asia, examples abound. It was demonstrated, for example, in art critic Leonidas Benesa’s article on Zóbel: “Zóbel himself is the least bothered about the universal character of his style, and is even glad about it. ‘After all,’ he says, ‘the vocabulary of art has become international in almost every respect.’”33 In a section describing the art scene of Malaysia, after independence from British colonial rule, Syed Ahmad Jamal implied Malaysian artists’ turn to abstraction when he said, “The art scene was shifting from low-key provincialism to high-profile universal internationalism.”34 An art critic writing of Damrong Wong-Uparaj, a Thai artist who turned to abstraction in the 1960s, remarked of him, “He has become known as the defender of abstraction and of ‘universalism’, which some of his critics take to mean Westernization.”35

The last quotation brings us to the paradox that abstraction, though “international” and “universal,” was also often co-opted by the “national”. If some thought of abstraction as Western, it was also because of the widespread branding of Abstract Expressionism as American. Guilbaut noted of the contradiction, “In order to be international and to distinguish their work done in the Parisian tradition and forge a viable new aesthetic, the younger painters were forced to emphasize the specifically American character of their work.”36 Because the aim of abstraction was not objective representation, art of the movement was malleable enough to conform to individual artistic sensitivities and bolster the agenda of particular national identities. This was true of the art of America but also elsewhere.

In Southeast Asia, this was particularly important in the post-World War II era, a time when many countries in the region were modernising and nation-building, following independence from colonial rule. Art’s role in representing national identity was a hotly-discussed topic and abstraction figured into the discussion because it was a dominant global trend. While abstraction and even semi-figurative forms were considered Western by some, others saw the possibility of it connecting to earlier local traditions. Syed Ahmad Jamal claimed that Abstract Expressionism was not, in Malaysia, a borrowed idiom. He believed it was a natural development from their watercolour tradition and found that its immediacy and mystical quality “appealed particularly to the Malaysian temperament, sensitivity[,] and cultur[al] heritage, and with the tradition of calligraphy found the idiom the ideal means of pictorial individuation.”37 Gregorius Sidharta Soegijo from Indonesia was spurred by the abstract patterns from local traditional arts for his sculptures and prints.38 Other artists rendered abstraction in the unique properties of a local medium, such as batik in Malaysia and lacquer in Vietnam, as one method of nationalisation.

Having played a significant role in the art scenes of both Spain and the Philippines, Zóbel represents a special case. While he had always been a Spanish citizen, it was noted that “he refers to the Philippines as ‘our country,’ to Filipino painters as ‘our artists,’ to Filipino art as ‘our art.’”39 He was among the artists representing the Philippines in the Spanish-American biennale in Havana in 1954, yet represented Spain in the Venice Biennale in 1962, after moving there permanently in 1961. His dual nationalism has made it tempting for others to look for Spanish and “Oriental,” if not specifically Filipino, characteristics in his practice. While he has stated that his Saeta series and subsequent Serie Negra series—black on white abstractions—were not consciously influenced by Asian calligraphy, it was easier and more convenient for people to read them as such.40 The black paint on a white surface was often associated with Chinese or Japanese calligraphy, but it was, for Zóbel, seemingly more motivated by eliminating the distractions of color than the influence of a particular culture.41 In contrast, Peter Soriano, in the catalogue of Zóbel’s posthumous exhibition at the Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University, wrote of one Serie Negra work as being reminiscent of the work of Spanish artist El Greco. He thought that for others to consider the series as “Oriental” was to misunderstand it.42 Zóbel remarked on the different interpretations of Serie Negra, “they may look Oriental in Spain, but I notice with some amusement that they look very Spanish when shown in the Orient.”43 To read a painting, most looked for identifying traits or markers, comfortable with points of sameness—or of difference.

Though he was comfortable enough to write about Philippine and Spanish art and speculate on its national identity, Zóbel usually tended to avoid labels on his own art. In all likelihood, he would have thought classifying his paintings as having Philippine and Spanish characteristics would invite unnecessary disruptions that might cloud people’s judgment and prevent them from examining the painting for itself. The premise of non-objective painting, after all, was that, in Zóbel’s words, the “subject of a painting is the painting itself.”44 To nationalise it would occlude its primary purpose.

Leonidas Benesa, surmising Zóbel’s art and national identity, cited R. Taylor, an American critic who had seen Zóbel’s work and likened him to the Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana. Zóbel also being between two countries, Taylor had conjectured the following to also ring true for Zóbel: he “was adrift between two worlds and managed to absorb the best of either so that it was equally impossible to tell where his allegiance lay; at bottom his nationality was the land of the human mind…”45

IV

Zóbel’s pursuit of visual pleasure of form on a flat surface led him to abandon representation to devote himself fully to the non-objective, or abstraction as is commonly understood today. His efforts, and those of other artists in the Philippines and in the region who turned to abstraction, were not without resistance by the public, who struggled to understand such paintings. Likely to some bewilderment, Zóbel expressed that his paintings were nothing else but paintings: “My pictures are statements, rather than gestures, criticisms, ornaments, imitations, constructions or all the other different things that a picture can be. I enjoy the other sort of thing but I paint what I paint."46 Other matters—those other than painting—were diversions, intrusions, and just clutter.

Though artists like Zóbel sincerely believed in abstraction and its international character, abstraction – particularly the influence of American Abstract Expressionism – was also deliberately cultivated as part of Cold War propaganda. That it could be “international” and “universal” were attractive words to associate with liberal human values and democracy, as championed by America. Abstraction could also be innovated and adapted to various contexts, leading to its widespread appeal to a region like Southeast Asia, as artists sought to make it their own and at times assimilate it to a nationalist agenda. This was the world of abstraction, but for artists like Zóbel, abstraction was simply a world in itself. Zóbel may have wished to reiterate his plea: “Pictures that don’t remind us of things and places, that don’t go well with the furniture…. Pictures that are merely meant to be seen and enjoyed in their own right. Every time we really look at a good picture we enter into one of the most exciting adventures available in our world."47

Editor's Note

This essay was published in Zóbel: Contrapuntos, edited by Guillermo Paneque (Makati: Ayala Museum, 2017). It is reproduced here with permission and minor edits.

Work from Zóbel's Saeta series is on display in Suddenly Turning Visible: Art & Architecture (1969–1989) and Between Declarations and Dreams: Art of Southeast Asia since the 19th Century.

Notes

- Entry on Fernando Zóbel in A Report Covering Seven Years of Philippine Contemporary Art [1951-1957] as noted through the Philippine Art Gallery (Manila: Philippine Art Gallery, 1958), 46. For consistency throughout the essay, direct quotations and sources which use Zóbel’s name without the diacritic have been changed to include it.

- “Malaya Wins First Prize in Art Tilt,” Manila Bulletin, 30 April 1957, 6. PKL Archives ART VII, 414. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc. The author has drawn materials from the archives of Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, which consist of clippings about art and culture, her notes, letters, invitations, and catalogs compiled into several scrapbooks. Because of the nature of these volumes, the precise source information for some of the materials are not readily available. This author has therefore cited “publication unknown,” “date unknown,” or “page unknown” for incomplete source information. The author has also relied on Purita’s handwritten notes that cite publication name and date, so the author acknowledges the possibility of human error. Citations in the footnotes identify the scrapbook and page numbers as referenced in the Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.’s pdf files where the archives are kept.

- Ricaredo Demetillo, “Fernando Zóbel: Man and Artist,” publication unknown, date unknown (c. 1956), 5. PKL Archives ART VI, 124. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Magtanggul Asa [Aurelio Alvero], The First Exhibition of Non-Objective Art in Tagala (Pasay City: House of Asa, 1954), 11. The other ten artists were Hernando R. Ocampo, Manuel Rodriguez Sr., Nena Saguil, Lee Aguinaldo, Jose Joya, Victor Oteyza, Leandro Locsin, Carl Steele, CV Pedroche and Fidel de Castro.

- Magtanggul Asa [Aurelio Alvero], “Non-Objectivism in Philippine Art,” Philippine Herald Magazine, 2 January 1954, 4.

- “AAP to Sponsor First Neo-Realist Art Exhibition,” Manila Times, 9 June 1950, 5. PKL Archives ART II, 3. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Magtanggul Asa [Aurelio Alvero], The First Exhibition of Non-Objective Art in Tagala, 10.

- Jerome Ashmore, “Some Differences between Abstract and Non-Objective Painting,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 13, No. 4 (June 1955): 488. Magtanggul Asa [Aurelio Alvero], “Non-Objectivism in Philippine Art,” Philippine Herald Magazine, 2 January 1954, 4.

- David Medalla’s Joyous Kingdom is in the Ateneo Art Gallery collection. Images of Arturo Luz’s City (different from the City in the Ateneo Art Gallery collection), Manuel Rodriguez’s Carousel and Hernando Ocampo’s Fiesta are reproduced in First Southeast Asia Art Conference and Competition (Manila: Art Association of the Philippines, 1957), n.p.

- Fernando Zóbel de Ayala, “Lecture Outline for the Course Introduction to Contemporary Painting,” Ateneo de Manila University Graduate School, 1954-1955, in Rod. Paras-Perez, Fernando Zóbel (Manila: Eugenio Lopez Foundation, Inc., 1990), 190.

- The categories for the AAP 11th Annual Art Exhibition in 1958 were non-objective, abstract, representational, special awards, sculpture, graphic arts, photography and purchase prize. Purita Kalaw-Ledesma and Amadis Guerrero, The Struggle for Philippine Art (Quezon City: Vera Reyes, 1974), 187. For preference to use the term non-figurative, see Leonidas V. Benesa, “Portrait of an Executive as Artist,” Sunday Times Magazine, 5 January 1958, 19. PKL Archives ART VIII, 266. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Rod. Paras-Perez, Fernando Zóbel (Manila: Eugenio Lopez Foundation, Inc., 1990), 38. The whole quotation is italicized in the original source.

- Fernando Zóbel, “An Artist Talks on Modern Art,” publication unknown, date unknown (c. 1956), 42. PKL Archives ART VII, 171. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Author unknown, “Zóbel,” This Week, 9 [? Day illegible] September 1956, 52-55. PKL Archives ART VII, 216-217. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Author unknown, “Fernando Zóbel’s Lines,” Woman and the Home, 8 August 1957, page unknown. PKL Archives ART VIII, 14. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Letter from F. Reyes to This Week, This Week, 15 August 1957, page unknown. PKL Archives ART VIII, 14. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- 1973 interview with Lee Aguinaldo in Cid Reyes, Conversations on Philippine Art: Interviews by Cid Reyes (Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1989), 120.

- Zóbel, “An Artist Talks on Modern Art,” 42. PKL Archives ART VII, 171. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Demetillo, “Fernando Zóbel: Man and Artist,” 4. PKL Archives ART VI, 123. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Peter Soriano, “Fernando Zóbel; A Biographical Sketch of Zóbel’s Formative Years,” in Pioneers of Philippine Art: Luna, Amorsolo, Zóbel (Makati: Ayala Foundation, Inc., 2006), 93.

- 1978 interview with Fernando Zóbel in Cid Reyes, Conversations on Philippine Art: Interviews by Cid Reyes (Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1989), 50.

- Paras-Perez, Fernando Zóbel, 12.

- Redza Piyadasa, “Syed Ahmad Jamal,” in Redza Piyadasa and T.K. Sabapathy, Modern Artists of Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Ministry of Education Malaysia, 1983), 85.

- Syed Ahmad Jamal, Syed Ahmad Jamal Retrospective (Kuala Lumpur: National Museum of Art, 1975). Quoted in Piyadasa, “Syed Ahmad Jamal,” 85.

- Piyadasa, “Syed Ahmad Jamal,” 86.

- The exhibition dates for Modern Art in the United States were 5 January – 12 February 1956 and or The New American Painting, the dates were 24 February to 22 March 1959. Tate Museum, “Tate Britain Exhibition: The New American Painting,” accessed 11 March 2017, http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/new-american-painting. Syed Ahmad Jamal studied in London from 1950 to 1956, briefly returned to Malaysia, and then taught at the Malayan Teacher’s College in Kirkby, England from 1958-1959. Piyadasa has noted that Jamal returned to Malaysia at the end of 1959. Jamal said he had seen the exhibition during the latter half of his stay as a student in England. While he completed his studies in 1956 and had been teaching by the time he left in 1959, it might be possible he was also referring to his overall stay in England rather than just the period he was a student. Jan Goldman, “Congress, operation,” in The Central Intelligence Agency: An Encyclopedia of Covert Ops, Intelligence Gathering, and Spies, ed. Jan Goldman (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2015), 82.

- Juan Manuel Bonet, “A tribute to Fernando Zóbel,” in Zóbel (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2003), 264.

- Goldman, “Congress, operation,” 82. Eva Cockcroft, “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War,” in Pollock and After: The Critical Debate, ed. Francis Frascina (New York: Harper & Row, 1985), 131.

- Cockcroft, “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War,” 129, 131. Former CIA case officer Donald Jameson, in talking about the CIA’s role in promoting Abstract Expressionism, has been quoted as saying, “We recognized that this was the kind of art that did not have anything to do with socialist realism, and made socialist realism look even more stylized and more rigid and confined than it was.” See Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid the Piper?: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War (London: Granta, 1999), 260.

- Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 196.

- Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art, 175.

- Kalaw-Ledesma and Guerrero, The Struggle for Philippine Art, 67.

- Benesa, “Portrait of an Executive as Artist,” 21. PKL Archives ART VIII, 267. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Syed Ahmad Jamal, Seni Lukis Malaysia – 25 Tahun (Kuala Lumpur: Balai Seni Lukis Negara, 1982), n.p.

- Hiram Woodward, Jr., “Damrong Wong-uparaj,” Bangkok World, 18 February 1965, 18.

- Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art, 175.

- Syed Ahmad Jamal, Seni Lukis Malaysia – 25 Tahun, n.p.

- Jim Supangkat and Sanento Yuliman, G Sidharta di Tengah Seni Rupa Indonesia (G Sidharta within Indonesian Art), trans. Joke Moeliono assisted by Titi Sudibyono and Wendy Gray (Jakarta: Penerbit PT Gramedia, 1982), 65.

- Author unknown, “Fernando Zóbel de Ayala: ‘Democratic’ is an inevitable word,” Woman and the Home, 13 May 1954, 7. PKL Archives ART IV, 245. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- That it was not consciously influenced, see 1978 interview with Fernando Zóbel in Cid Reyes, Conversations on Philippine Art: Interviews by Cid Reyes, 50.

- Paras-Perez, Fernando Zóbel, 38. See also Rafael Pérez-Madero, “About Fernando Zóbel’s painting,” in Zóbel (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2003), 273.

- Peter Soriano, Creative Transformations: Drawings and Paintings by Fernando Zóbel (Boston: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, 1987), n.p.

- Quoted in Paras-Perez, Fernando Zóbel, 57.

- Zóbel de Ayala, “Lecture Outline for the Course Introduction to Contemporary Painting,” in Paras-Perez, Fernando Zóbel, 190.

- R. Taylor quoted in Benesa, “Portrait of an Executive as Artist,” 21. PKL Archives ART VIII, 267. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Fernando Zóbel quoted in Benesa, “Portrait of an Executive as Artist,” 21. PKL Archives ART VIII, 267. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.

- Zóbel, “An Artist Talks on Modern Art,” 42. PKL Archives ART VII, 171. Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation, Inc.