Edhi Sunarso: A Life Through Archives

Edhi Sunarso is known for his monumental sculptures, many of which have come to define the cityscape of Indonesia's capital, Jakarta. Using archival material ranging from a student card and personal photos to newspaper clippings, Gerald Sim gleans insights into Edhi's artistic practice while examining the socio-political circumstances of post-war Indonesia.

Dirgantara (Airspace), 1963

Bronze

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

2012-00450

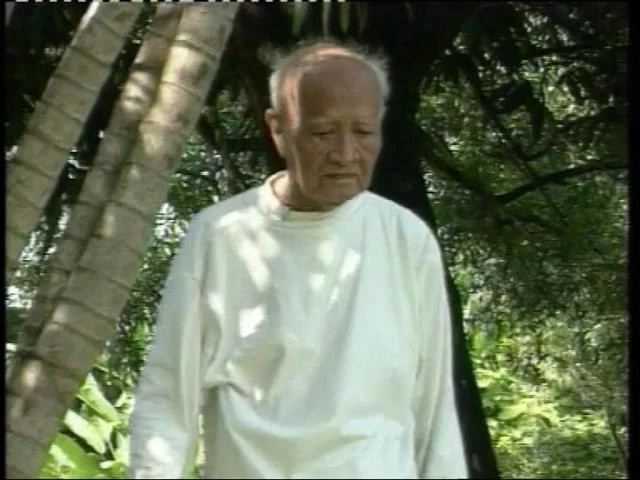

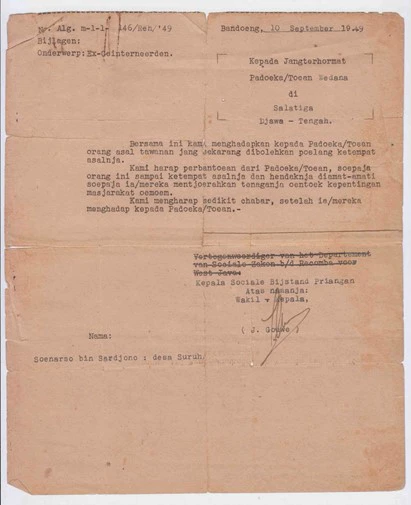

To examine Edhi Sunarso’s body of works is to examine the socio-political background of post-war Indonesia. Born in Salatiga, Central Java, in 1933, Edhi Sunarso’s primary education was interrupted by the raging Indonesian independence struggle against Dutch colonial presence. He joined the guerilla forces and rose to become commander of a sabotage force that fought in West Java. In 1946, at the very tender age of 13, he was captured by the Dutch forces and held as a geïnterneerde—an intern. Unlike the author, his internship was conducted not in the air-conditioned comfort of National Gallery Singapore but at the Kebonwaru Prison, Bandung.

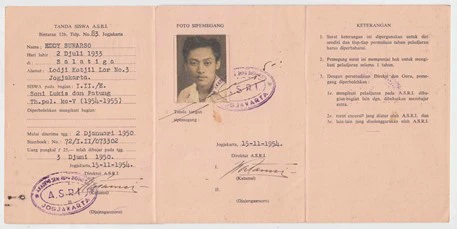

While held captive, Edhi Sunarso learnt English, Bahasa Indonesia, arts and crafts and drawing from older prison inmates. He was released three years later in June 1949, shortly before his 17th birthday. Eager to rejoin the Indonesian armed forces, he would walk to the KUDP (Kantor Urusan Demobilisasi Pejuang, the Fighters Demobilisation Affairs Office) in Yogyakarta every day in search of opportunities. It was during these daily journeys that he first encountered students from ASRI (Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia, Indonesian Fine Arts Academy) painting outdoors. Edhi would sit at the back of the class and join in painting practice. Hendra Gunawan, who was then an instructor in ASRI, noticed Edhi during these classes and with the help of Hendra Gunawan, as well as other ASRI instructors Affandi and Katamsi, Edhi was accepted as a student in painting and sculpture at the Academy in 1950.

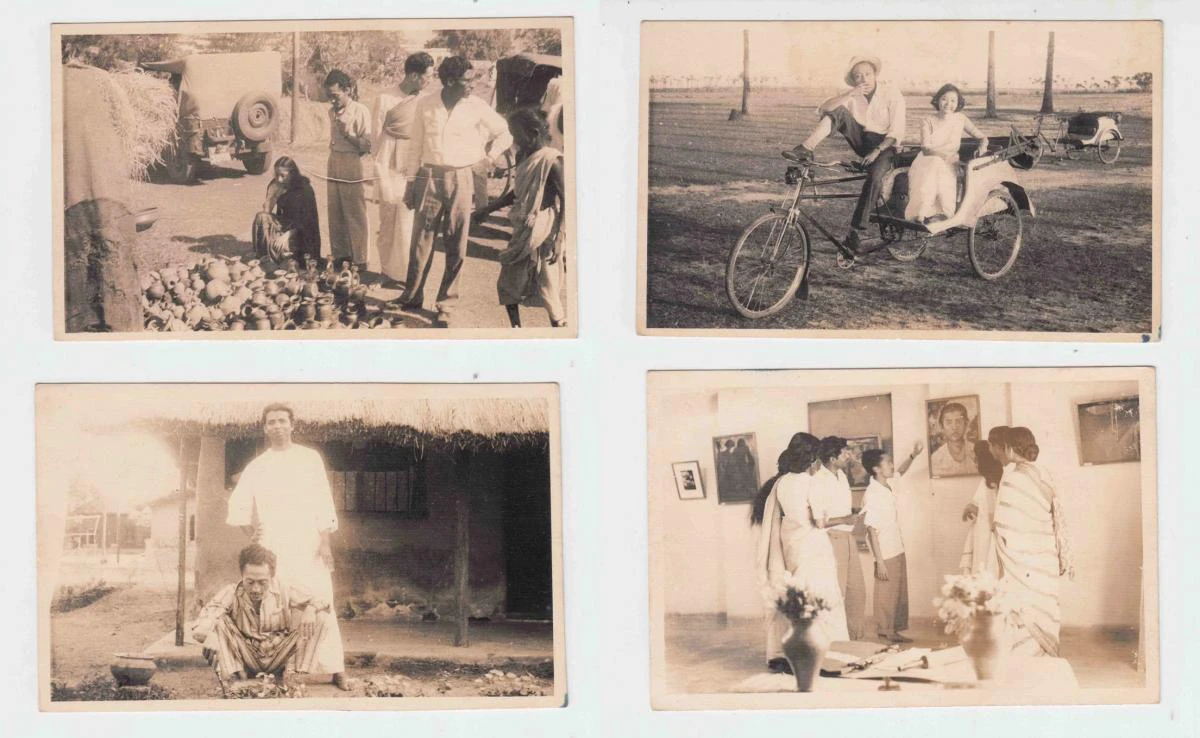

Upon graduation, Edhi was awarded a UNESCO scholarship to pursue studies at Visva Bharati Santiniketan University in India. Founded by the Bengali artist, poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore, Santiniketan featured a unique curriculum founded on pan-Asian ideas. Here, Edhi and other prominent figures such as the Indonesian painters Rusli and Affandi, Burmese illustrator Bagyi Aung Soe, and Thai painter Fua Haribhitak were taught in the open air in a rural locale. The nationalist bent of education in Santiniketan contibuted greatly to these artists' notions of identity and belonging in a post-colonial Asia.

Edhi returned from Santiniketan to an Indonesia reeling from post-nationalist fervour under the leadership of the first Indonesian president, Sukarno. While Nikita Kruschev, then Prime Minister of the Soviet Union, dismissed monuments as “pants” to a country that needs bread and rice to get stronger, Sukarno believed that monuments were “food for the soul” for an Indonesia ready to show itself on the global stage. Soon after, he would begin working closely with Edhi to build sculptures that would come to define the cityscape of Indonesia's capital, Jakarta.

In 1958, Edhi was summoned by Sukarno to work on the Selamat Datang (Welcome) monument. Having never created a bronze sculpture before, he was initially hesitant in accepting the offer. An indignant Sukarno replied: “Do I have to summon a foreign artist to work on our very own monuments?” Unable to refuse such a strong request, the monument was unveiled in time for the fourth Asian games in 1962. Featuring a young man and woman with a bouquet in tow, the expressive monument captures the elan of the capital of a modern, young, nation.

Edhi enjoyed a close relationship with Sukarno. He recalled Sukarno as an unfailingly passionate character, ever-humorous and charismatic. “Bung Karno [President Sukarno] was always full of fire when speaking about patriotism and the struggle of the Indonesian republic. That zeal infected me, fuelling the creation of my monuments despite the occasional fatigue. Additionally, at times when we were working on the monuments, Bung Karno made the time to visit us. He frequently entertained us with his jokes, as if we were his friends. We were always very appreciative of that, and in awe at his personality as a result.”

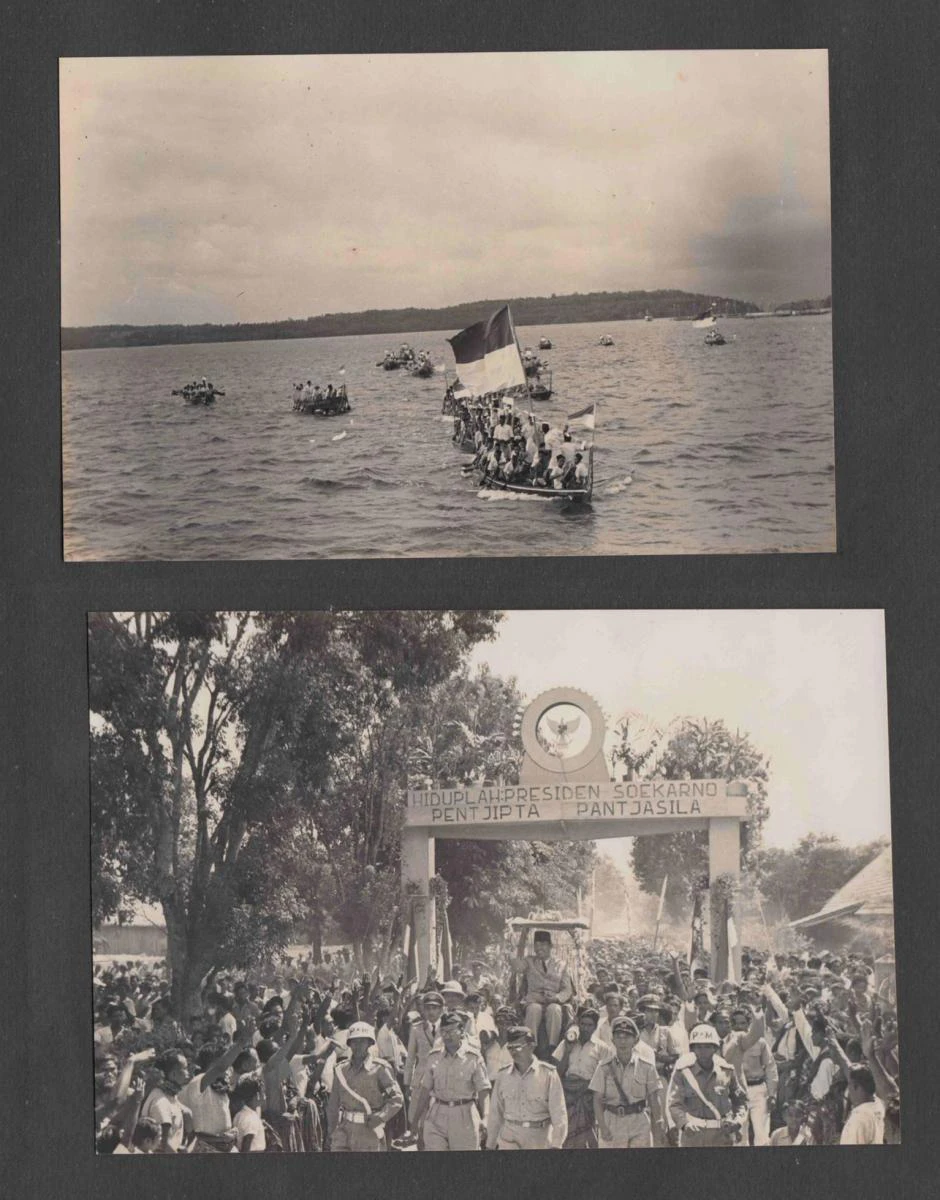

The Monumen Pembebasan Irian Barat (West Irian Jaya Liberation Monument) was unveiled in 1963, shortly after West Papua (formerly known as Irian Jaya) was transferred from Dutch administration and became part of Indonesia. A maquette of this monument is on display just outside the Rotunda Library & Archive. The statue depicts a man with his arms outstretched, breaking free of his chains. It sits in Lapangan Banteng, Jakarta, atop a 36-metre high pedestal.

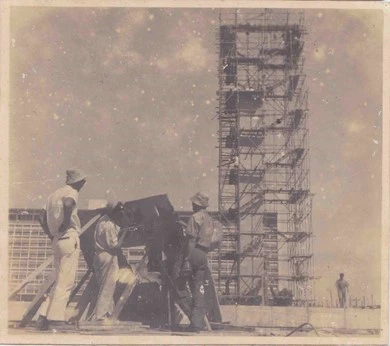

The lead-up to the construction of the Dirgantara (Airspace) monument in the 1960s was a particularly emotional time for Edhi. In 1964, Sukarno foreshadowed his eventual downfall by declaring it Tahun Vivere Pericoloso (The Year of Living Dangerously). Sweeping political changes taking hold of Indonesia reached an apex when the G30S (Gerakan 30 September, 30th September Movement) deposed Sukarno in 1965 and installed the Orde Baru (New Order) regime that would continue for nearly four decades under the iron fist of Suharto.

On the day of the G30S itself, Edhi waited for Sukarno to report on progress on the monument. He was later alerted of the Movement and told that Sukarno was not coming. On reaching the state palace gates on his return home, he was surprised to find the gate surrounded by rebel forces.

Sukarno’s failing health meant that he could not officiate Dirgantara upon its completion in 1966. Edhi’s works became more and more abstract and divorced from revolutionary themes in the following years. He continued teaching at ISI (Institut Seni Indonesia, Indonesian Arts Institute), where he and his contemporaries faced their very own “coup d’etat,” the rebellious Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (The New Art Movement) which emerged in 1975. In a 1979 article by Bonyong Munni Ardhi, the Movement criticised the ASRI teaching staff as being "no longer creative artists, rather, increasingly concerned with being good civil servants […] Obsessed with being ordered around: [once in a while they create] monuments and are invited to show at exhibitions. Their work is compromised by those who give them orders.”

On 4 January 2016, Edhi died of acute respiratory infections in Yogyakarta. He left behind monuments that live on today, continuing to serve as constants in an ever-changing city, silently reminding us of the ebbs and flows of history that defined his monumental career.

An exhibition of archival material relating to Edhi’s life, some of which are reproduced here, are on display at the National Gallery Singapore Library and Archive.

References and Further Reading

Edhi recounts his experience building monuments in a section of the catalogue for his solo retrospective exhibition Monumen, held in Jakarta in 2010; an English translation is also available in the publication. View the catalogue on the Indonesian Visual Arts Archive (IVAA).

On Kruschev and Sukarno on monuments, see “Makanan Jiwa dari Sang Pematung” (Food for the Soul from the Sculptor) on IVAA (link in Bahasa Indonesia).

On the article by Bonyong Munni Ardhi criticising ASRI, see “Menutup Diri Terhadap Dunia Luar” (Closing the Self to the World Outside) at IVAA (link in Bahasa Indonesia).