Excerpt from “The Tender Insistence of Ruthless Remembering” in Living Pictures (2022) edited by Charmaine Toh. Available for access in its entirety, on Project Muse and JSTOR.

II. The Tender Insistence of Ruthless Remembering

- Sze Ying Goh, Curator at National Gallery Singapore

The camera does not lie, but its artful ability to isolate a moment has been the most seductive tool for this apparatus in its long history of shaping our habits of seeing. Inherent to the production of the photographic image is the Janus-faced split between showing and selecting: an operation that has historically differentiated photography from painting. Unlike a painter, a photographer can never add a detail into the picture after the fact (unless manipulated in the darkroom or with software). This is the distinction between being taken and being made.1 In spite of the photograph’s mimetic ability to depict reality—what Barthes terms as an “analogical perfection”—the photographic image flits furtively between exactitude and context.2 Visual details are cropped out in favour of compositional, ideological or cultural factors; nonetheless these decisions are often assumed as the photographer’s natural impulse to enhance the veracity of their subject.3 Photojournalism’s ur-hero Henri Cartier-Bresson equates the photographer’s flair as “the decisive moment,” an instance when a “satisfying” picture meets the revelation of “a truth about the subject.” 4 For Cartier-Bresson, the decisive appears to be simultaneously discerning: the photographer’s reflex manifests his technical virtuosity with the camera—a characteristic which separates the great from the average. Virtuosity very rarely discloses the intentions of the photojournalist, how the sum of their politics and prejudices shapes their coverage.

When probed, we find our faith in the press photograph—of showing things and events as between image and text 5. In order for their objective and descriptive qualities to translate, even the most decisive photographs have generally relied on words before they can tell a thousand more. This assumed realism of the picture is in fact naturalised with the aid of captions, as Barthes outlines: “a press photograph is never without a written commentary.” 6 This essay centres upon the recuperative approaches taken by four artists in the Living Pictures exhibition which problematise representation and the circulation of the image, particularly those used in reportage. While each artist has a distinctive practice, in these selected works they share a similar interest in mining images found in mass media to draw out the complex relationship between photojournalism and its construction of history, and the way we see and understand the world.

Photojournalism came to prominence in the 1930s as a result of the introduction of handheld cameras in the mid-1920s, which led to a rising popularity in illustrated essays in widely circulated picture magazines, such as LIFE and Look in the United States, and Münchner Illustrierte (Munich Illustrated) and Vu in Europe. Media magnate Henry Luce, who bought LIFE in 1936 and engineered its pictorial turn, articulated emphatically the publication’s maxim: “to see life; to see the world.” 7 Luce knew that texts without pictures would sell fewer magazines, while photographs without captions failed to exploit the full spectrum of the reader’s imagination. At its height, LIFE reached one in three American readers; some of the most iconic images of the 20th century adorned its covers in the age preceding television. It is hard to ignore the fact that the demand for pictorial appeal, even in the venerated sphere of documentary photography, was largely shaped by market forces. Social theorist Susie Linfield aptly surmises that photography’s “original sin” lay in its supine relationship with consumerism. 8 In the 1960s, LIFE published various series of pictorial volumes, including the LIFE World Library anthology. This ambitious publication project took six years to complete, with an aim to “present a comprehensive interpretation of the principal nations and peoples of the contemporary world.” 9 While the volume has been translated into 13 languages and circulated in over 90 countries, the majority of the writers are American and British. One of the editorial decisions for how the volumes are grouped is “its special relevance to American readers.” 10 The criterion comes as no surprise given Luce, then editor-in-chief of LIFE, wrote in a 1941 editorial that “the American people are by far the best-informed people in the history of the world,” a not-too-audacious statement considering it coincided with the rising political dominance of the US. 11 LIFE World Library is an unabashed expression of the American view of the world, to the rest of world.

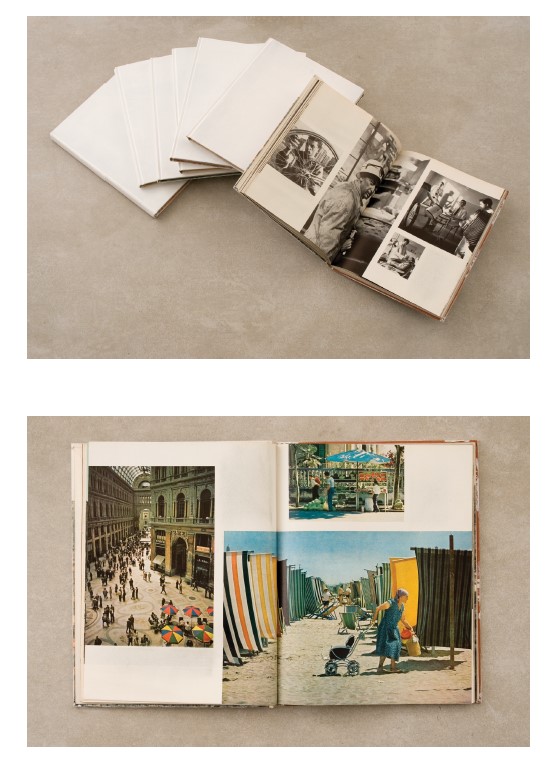

In Simryn Gill’s (b. 1959) 32 Volumes, 32 volumes from the LIFE World Library anthology are stripped bare by hand. The original titles and images on the hardcovers are painted over in gesso, while the printed text on the inside pages has been meticulously sandpapered away. The work serves up documentary photography in its most rudimentary form—a Barthesian purity of image without text—which in turn demonstrates the ambiguity that lurks behind every photograph.

As with Gill’s other works, her interventions stem from her “fascination with the limit of rational knowledge, and with the instability of images and texts as forms of representation.”12 Gill obtained several sets of the anthology from a second-hand bookstore, a place that fits suitably with her compulsion for collecting. Objects and detritus often find their way into her personal radius, both fortuitously and with purpose: books, magazines, shrines, things washed up on the beach or crushed on the road, discarded and lost knick-knacks found on the street, fruit seeds and garden overgrowth. Gill gathers things to take them apart, alter or rearrange them, in a nebulous fashion that reveals changefulness, chipping away preordained ways of seeing the world. 13 Gill’s interventions with books speak more of her love for them—for reading and as objects—and from which her awareness of how the written word is imbricated in the power structures of problematic histories stems. It is as if she knows too well—and wants us to realise, too—that while representation is a function which reveals and clarifies the world, it is also the operation of how power begets power.

Endnotes

-

John Szarkowski, The Photographer’s Eye (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2007), 9. ↩︎

-

Roland Barthes, “The Photographic Message,” in Image-Music-Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 17. ↩︎

-

In his essay “The Photographic Message,” Barthes describes how “the photograph allows the photographer to conceal elusively the preparation to which he subjects the scene to be recorded by way of effects, staging, stylistic or syntactical preferences. For more, see Barthes, op. cit., 19–2. ↩︎

-

Peter Galassi, Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Early Work (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 9. ↩︎

-

Barthes refers to the photographic code” insofar as the image is an analogous reproduction of the object’s reality. However, Barthes explicates the paradox of (press) photograph as a co-existence of rhetoric and image, of objective and invested, of natural and cultural. See Barthes, op. cit., 16–31. ↩︎

-

Barthes, op. cit., 16. ↩︎

-

The phrase is taken from a longer excerpt: “To see life; to see the world; to eyewitness great events; to watch the faces of the poor and the gestures of the proud; to see strange things—machines, armies, multitudes, shadows in the jungle and on the moon; to see man’s work—his paintings, towers and discoveries; to see things thousands of miles away, things hidden behind walls and within rooms, things dangerous to come to; the women that men love and many children; to see and take pleasure in seeing; to see and be amazed; to see and be instructed” from the original prospectus of LIFE. See LIFE 5, no. 2 (11 July 1938): i. ↩︎

-

The surfeit of scepticism directed at documentary photography has been reflexively discussed in Susie Linfield’s book The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence (London: The University of Chicago Press, 2010). Her opening chapter jocularly titled “A Little History of Photography Criticism; or Why Do Photography Critics Hate Photography?” tracks the criticism mounted on documentary photography mapped across a range of curators, historians, even artists—a list which includes Douglas Crimp, Carol Squiers, Rosalind Krauss, Allan Sekula and Martha Rosler. See Linfield, op. cit., 3–12. ↩︎

-

The anthology contains 34 volumes, 32 are dedicated to countries—the major ones have their own volume to itself, while others are included in regional categories. The 2 supplementary companion books Handbook of the Nations and Atlas of the World serve as extended endnotes in this pictorial encyclopedia. See Oliver E. Allen, ed., LIFE World Library: Handbook of the Nations and International Organisations (New York: Time Incorporated, 1966), 6. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 7. ↩︎

-

Henry Luce, “The American Century,” in LIFE 10, no. 7 (17 February 1941): 61–5. ↩︎

-

Russell Storer, “Simryn Gill: Gathering,” in Simryn Gill (Sydney: MCA & Koln: Verlag der Buchhandlung, 2008), 45. ↩︎

-

The term “changefulness” comes from Ross Gibson’s essay which charts Simryn Gill’s work in relation to Australia’s history in “Motility” in Simryn Gill: Here art grows on trees (Belgium: MER and Australia Council for the Arts, 2013), 259. ↩︎