Excerpt from “Living Photographs” in Living Pictures (2022) edited by Charmaine Toh. Available for access in its entirety, on Project Muse and JSTOR.

I. Living Photographs

- Charmaine Toh, Former Senior Curator at National Gallery Singapore

Since its invention, photographic practices have been integral to visual culture and art in Southeast Asia, but recognition of their specificities have yet to be fully discussed. Photography in Southeast Asia has thus far been largely left out of both photographic and art histories, even those of its own nations. Ironically, this exclusion has allowed such photographs to “live” outside the established historical canons and so offer an opportunity to tell alternative histories. Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia looks at the power of photography in affecting the way we see and approach the world, and its mobilisation n systems of knowledge and representation since it arrived in the region in the mid-19th century.

This is not an attempt to draw regional or national boundaries, nor to identify a characteristic or style of photography, but to bring out certain practices and developments in this part of the world. As scholars increasingly recognise the need to address the dominance of Eurocentric histories and knowledge, the research for this exhibition offers an additional strand in the tapestry that is the global history of photography.

In the attempt to take some tentative steps towards photography’s own history in this region, the curators of Living Pictures have consciously avoided the existing frameworks of photographic histories, particularly the Museum of Modern Art model, which is largely driven by stylistic developments in a reactive chronology.1 More generally, the way the exhibition has been organised eschews such formalist art historical categories of style and technique. Instead, the overarching question the exhibition asks is: what do photographs do? The search for answers has been productive. Photographs have lives—they move and they act—and in the process, they affect the world around them.

By looking beyond the image, the exhibition draws out the conditions of production and reception of photography in Southeast Asia and the ways it has shaped the visual imaginary of the region, for itself and for others. Living Pictures is the culmination of the Gallery’s extensive research and collecting efforts in photography since we opened in 2015, when the medium was identified as a gap in our understanding of the histories of modern art in the region. As the first substantial survey of its kind, it highlights the important role photography has played in the development of visual culture and lays the groundwork for future research by others.

As the most ubiquitous visual medium of the modern age, photography has had a tremendous impact on the way we see the world, and ourselves. The power of photography is deeply tied to a discourse of “truth” and the history of its own development and use since its invention in France in 1839. Photography’s ability to capture a perfect, never-seen-before likeness was quickly appropriated by scientific and government agencies for use as documents, evidence and records. However, rather than thinking about photography as a reflection of the world, this exhibition asserts that photography has shaped our understanding of the world. Living Pictures reveals the roles photographs have played in imperialism and nationalism, in constructing and asserting modernities, and in challenging class and gender hierarchies. What is made visible and what is left out? And how does this change the way we engage not just with the image, but with the photographic object?

THE COLONIAL ARCHIVE

Early photography played an important role in visualising the world, and that included Southeast Asia. Photography’s history in Southeast Asia was closely linked to exploration, travel and its vaunted ability to accurately depict the world around it. The camera lent the explorer both status and credibility; it became a metaphor of objectivity. The earliest extant photograph made in Southeast Asia was Jules Itier’s (1802–1877) daguerreotype of the Thian Hock Keng temple in Singapore in 1844.2 The 1850s onwards saw a large number of itinerant European photographers travelling through parts of Southeast Asia. These travelling photographers typically spent a few months in one city providing their services before moving on to other nearby cities. They would then sell their works to illustrated magazines, publishers or even directly to customers, which included the European residents in the various Southeast Asian cities as well as the general public in Europe. This first section of the exhibition, “Colonial Archive,” recognises that many of the photographs made during this period resulted from European aims and desires. As such, they present a particular type of imperial gaze.

In a lecture on photography and exploration to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1891, John Thomson (1837–1921) claimed: “Where truth and all that is abiding are concerned, photography is absolutely trustworthy and the work now being done is a forecast of a future of great usefulness in every branch of science.” 3 Thomson was a Scottish photographer and one of the earliest to travel to Asia. He received significant recognition for this work, which brought images of the Far East to the audiences in Europe interested in finding out more about foreign lands and peoples. Thomson’s photographs were shown in lectures as well as books and magazines, and of course sold to individuals who often assembled them in albums. Such photographs not only satisfied the curiosity of the European public but also played a crucial part in conveying the extent and power of their empires. This was supported by the belief in photography’s autonomy and neutrality.

However, in his book Picturing Empire, James Ryan has demonstrated how the photographs made for British consumption in the 19th century revealed

“as much about the imaginative landscape of imperial culture as they do about the physical spaces or people pictured within their frame.” 4

While Ryan’s book focused on the British Empire, this is equally true of images of the Dutch and French colonies. Consider the album owned by Charles McWhirter Mercer (1828–1884) with views of Punjab, Kashmir, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Penang, Singapore and Java. Within it are a large number of photographs of newly built infrastructure such as roads and buildings, all carefully composed to present visually pleasing scenes. Even the photographs of the countryside are picturesque landscapes, rather than untamed tropical jungles filled with wild beasts (see John Thomson. The Waterfall Penang. c. 1876. Albumen print on paper, 38.8 × 29.2 cm. Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum, National Heritage Board, Singapore.). The images conveyed the civilising benefits of colonialism while also “domesticating a potentially hostile landscape.” 5 They offered a deliberate balance of the foreign and the familiar.

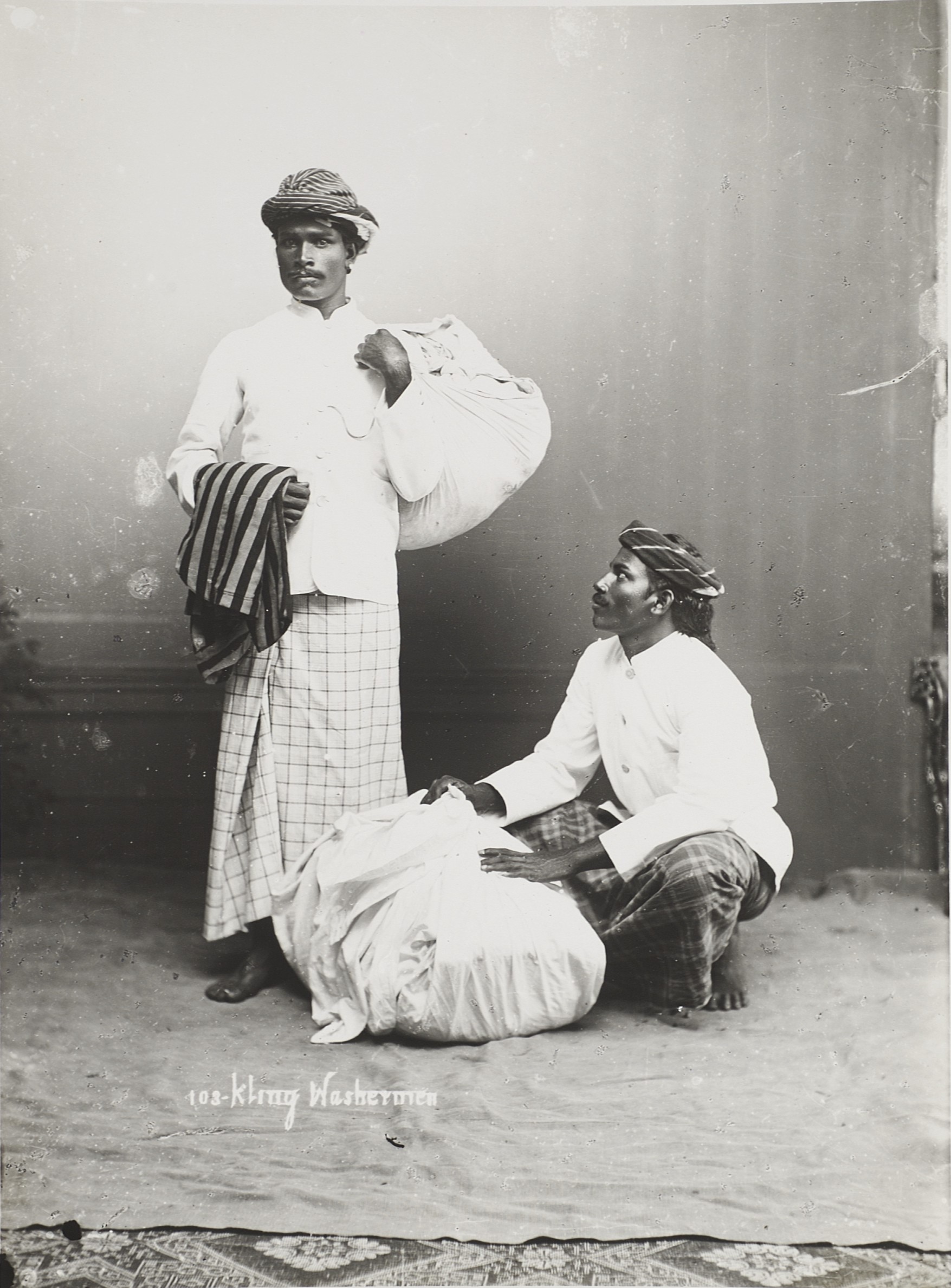

The photographic studio of G.R. Lambert & Co. was also aware of what its customers wanted. Active in Singapore from 1867 till 1918, the studio had one of the largest catalogues of images—over 3,000 from different parts of Southeast Asia— including landscapes and images of people of various races, which sold extremely well to tourists and residents. 6 It is important to note that the latter were not portraits in the traditional sense but were closer to ethnographic studies. Such photographs are described as “types” rather than “portraits” because the people in them were depicted as observed subjects rather than individual personalities. For example, the photograph of two Indian men had the caption of “Kling Washermen” and showed them posing with bags of laundry.

Endnotes

-

Christopher Phillips has traced the story of MoMA’s department of photography through the reign of its three directors Beaumont Newhall, Edward Steichen and Jan Sarkowski, effectively demonstrating the way the museum produced a version of photographic history that was “in truth, a flight from history.” Christopher Phillips, “The Judgment Seat of Photography,” October 22 (1982): 63. ↩︎

-

Gilles Massot, “Jules Itier and the Lagrené Mission,” History of Photography 39, no. 4 (2015): 319–47. ↩︎

-

John Thomson, quoted in James R. Ryan, Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire (London: Reaktion Books, 2013), 24. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 20. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 51. ↩︎

-

John Falconer, A Vision of the Past: A History of Early Photography in Singapore and Malaya: The Photographs of GR Lambert & Co., 1880–1910 (Singapore: Times Editions, 1987), 5. ↩︎

Bibliography

- pl. 37

- John Thomson. The Waterfall Penang. c. 1876. Albumen print on paper, 38.8 × 29.2 cm. Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum, National Heritage Board, Singapore.