The World of Georgette Chen through Her Archive

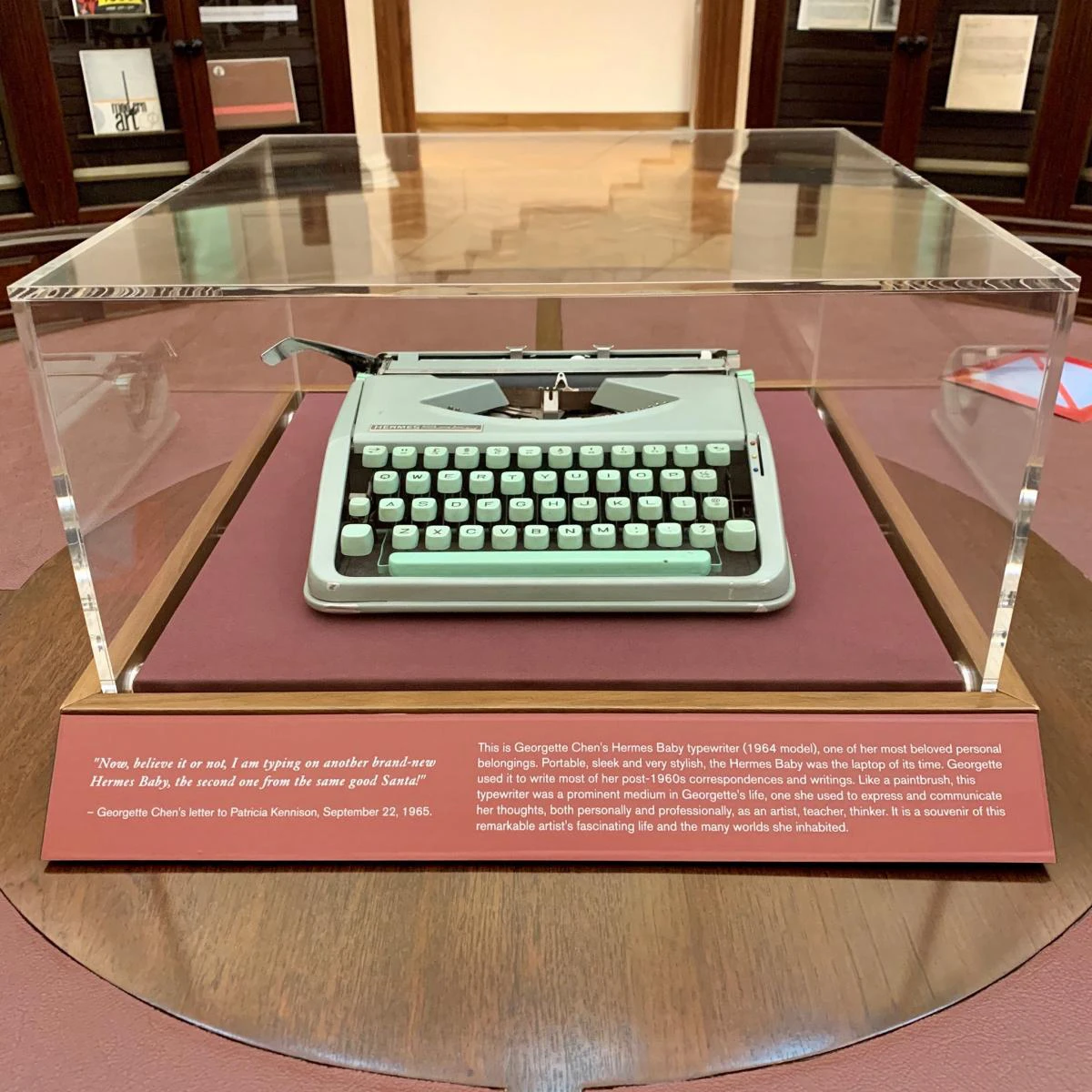

With photographs, sketches and writings, archival materials contain valuable first-hand information on artists’ professional practices. Michelle Tay introduces us to the Gallery's Georgette Chen Archive, which includes her beloved Hermes Baby typewriter as well as hand-drawn menu cards, providing us with a rare and intimate look into Chen's thoughts, observations and life.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.1-23.

The exhibition Georgette Chen: At Home in the World runs from 27 November 2020 to 26 September 2021 at the National Gallery Singapore. This major retrospective of the artist features 69 artworks alongside 74 pieces of archival material, drawn from the National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive as well as other public and private collections.

Archival materials often contain valuable first-hand information on artists’ professional practices, their thoughts and writings, and their views of the world through photographs and sketches. These materials greatly contribute to the study of the artist’s oeuvre, as they provide another dimension to understanding the artist beyond their works.

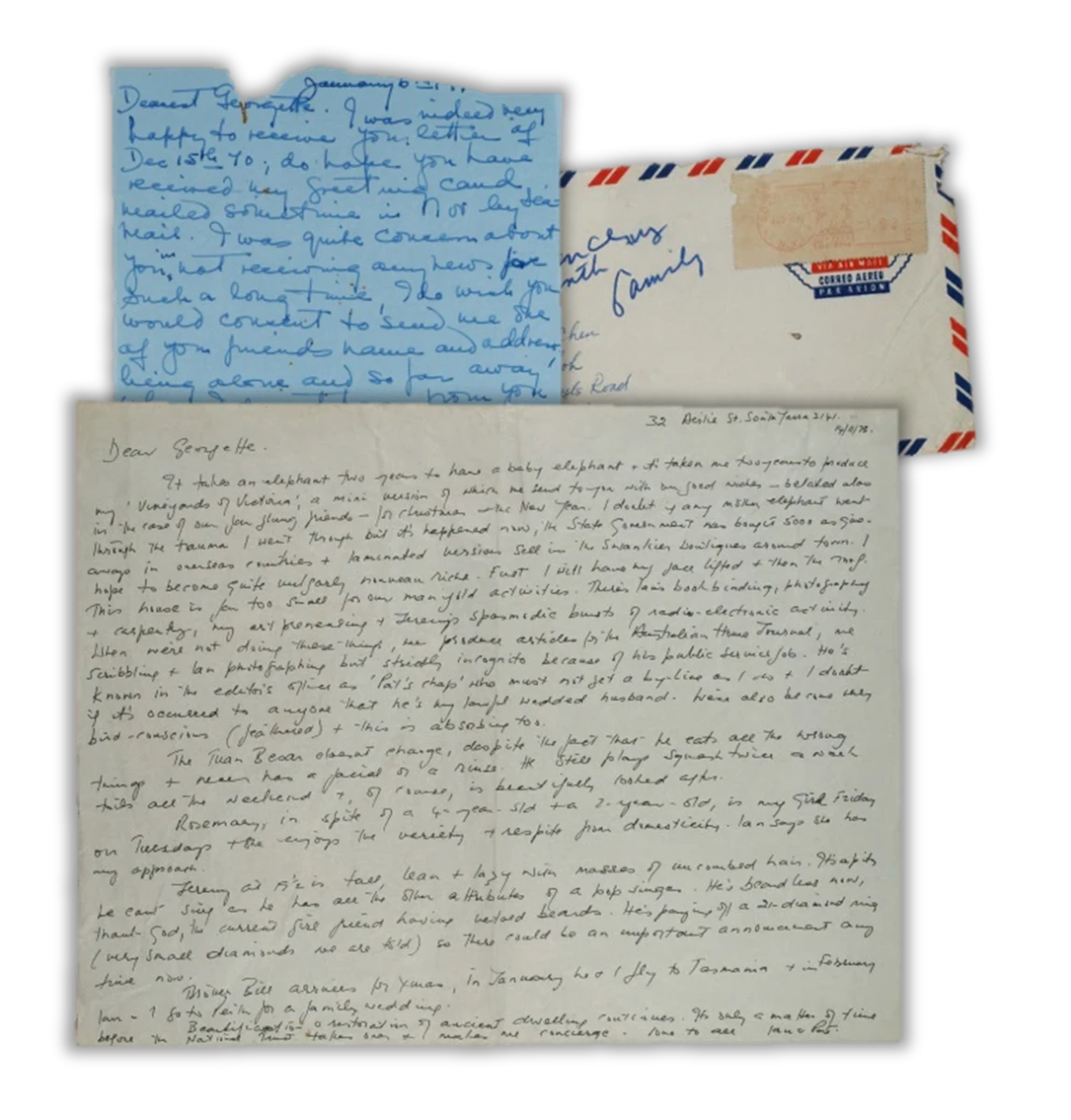

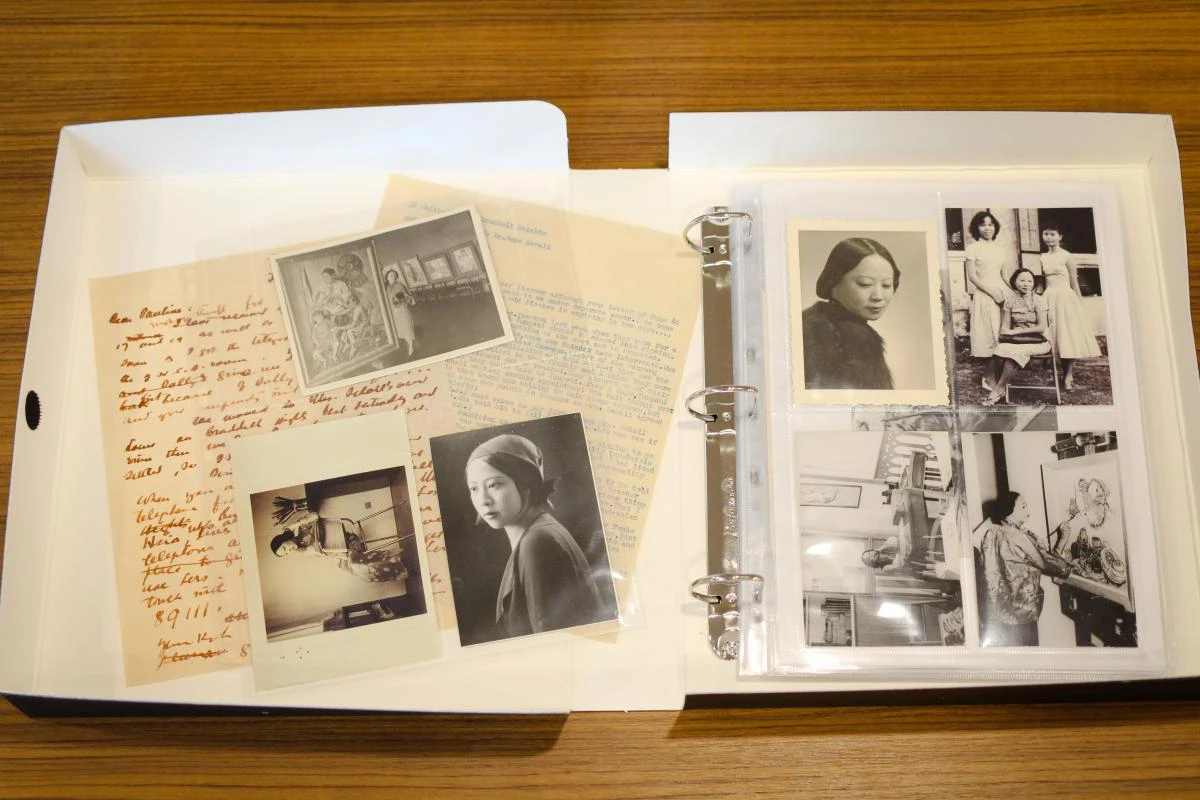

Among the holdings in the Gallery Library & Archive, the Georgette Chen Archive is one of the largest for an individual artist. It consists some 1,000 letters that Chen wrote to and received from her friends and family from 1949 to the 1980s, as well as her diaries, photographs, official records, newspaper clippings, and personal belongings including her Hermes Baby typewriter and Malay-language books. Together, they offer a rare and intimate look into her thoughts, observations and life, allowing for a deeper study into how these shaped her practice. It is remarkable that Chen kept such complete records of her papers and documents, even retaining the carbon copies of letters she sent. This provides archivists and researchers with invaluable access to the correspondence between her and her acquaintances, and suggests that Chen possessed the instincts of an archivist herself.

Chen’s archive was initially donated by the Lee Foundation to the Singapore Art Museum in 2003, and subsequently registered into the Gallery Library & Archive’s Collection. The Gallery has since undertaken much work to digitise, transcribe and annotate the materials with the aim of increasing their accessibility. The task is made more challenging by the various languages Chen used in her letters, including English, French and Malay, as well as the cursive script in which some of the letters and diaries were written. Work on adding annotations and descriptions for the materials is still ongoing with the help of volunteers.

The Gallery Library & Archive seeks to share its collections as widely as possible, with the aim of promoting research and scholarship. Over the course of these efforts however, the Library & Archive team faced the challenge of handling private information found within Chen’s personal correspondence and documents. Codes of ethics for the profession, on how to handle private and confidential information found in archives, have been drawn up by various professional bodies, such as the International Council on Archives and Society of American Archivists. The former cautions that archivists “must respect the privacy of individuals who created or are the subjects of records, especially those who had no voice in the use or disposition of the materials” [emphasis added].1 Similarly, the Society of American Archivists advocates that archivists:

recognize that privacy is an inherent fundamental right and sanctioned by law. They establish procedures and policies to protect the interests of the donors, individuals, groups, and organizations whose public and private lives and activities are documented in archival holdings. As appropriate and mandated by law, archivists place access restrictions on collections to ensure that privacy and confidentiality are maintained, particularly for individuals and groups who have had no voice or role in collections’ creation, retention, or public use

In Singapore, the Personal Data Protection Act also safeguards personal data such as addresses, phone numbers and identity numbers, especially for living persons. The Gallery Library & Archive recognises that the Georgette Chen Archive was donated by the trustees of Chen’s estate after her death, and contains information on Chen and many individuals who have had no say in the release of these materials. As such, priority has been placed on making available materials that relate to her artistic career, since it is the primary interest for those who wish to access her archive. Access to personal papers is restricted, and requests to view them are reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

The materials in the Georgette Chen Archive can be grouped into the following categories.

1. Letters

Together, Chen’s letters tell the story of her life, documenting the various events that unfolded: from 1949 when she was in Paris (her earliest letters in the Library & Archive’s collection are from this time), to her move to Penang and Singapore in the early 1950s, and up to the 1980s. At every stage of her life, she had close friends who she constantly corresponded with, and they provided a strong network of support for her life and artistic career. Even as new acquaintances she meets in Singapore enter her life, the occasional letters from her family and former classmates in New York, Paris and Shanghai allowed her to maintain the links with her roots.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2.

2. Personal documents and memorabilia

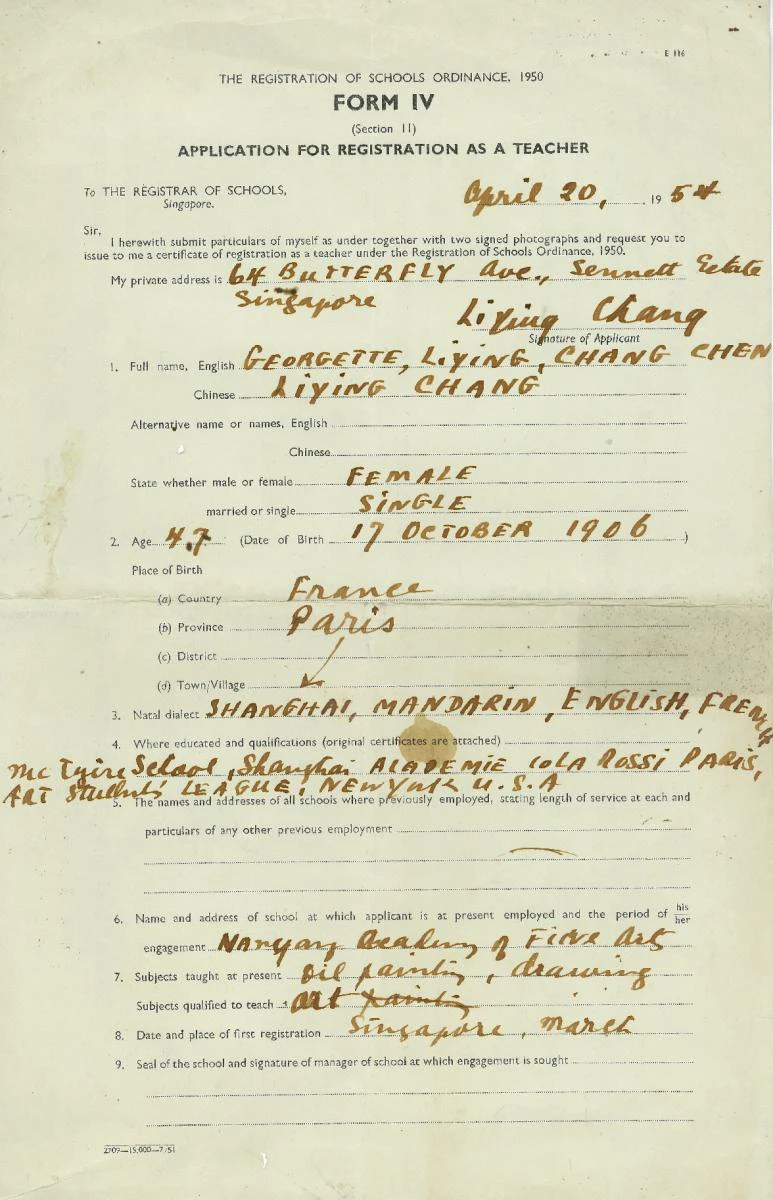

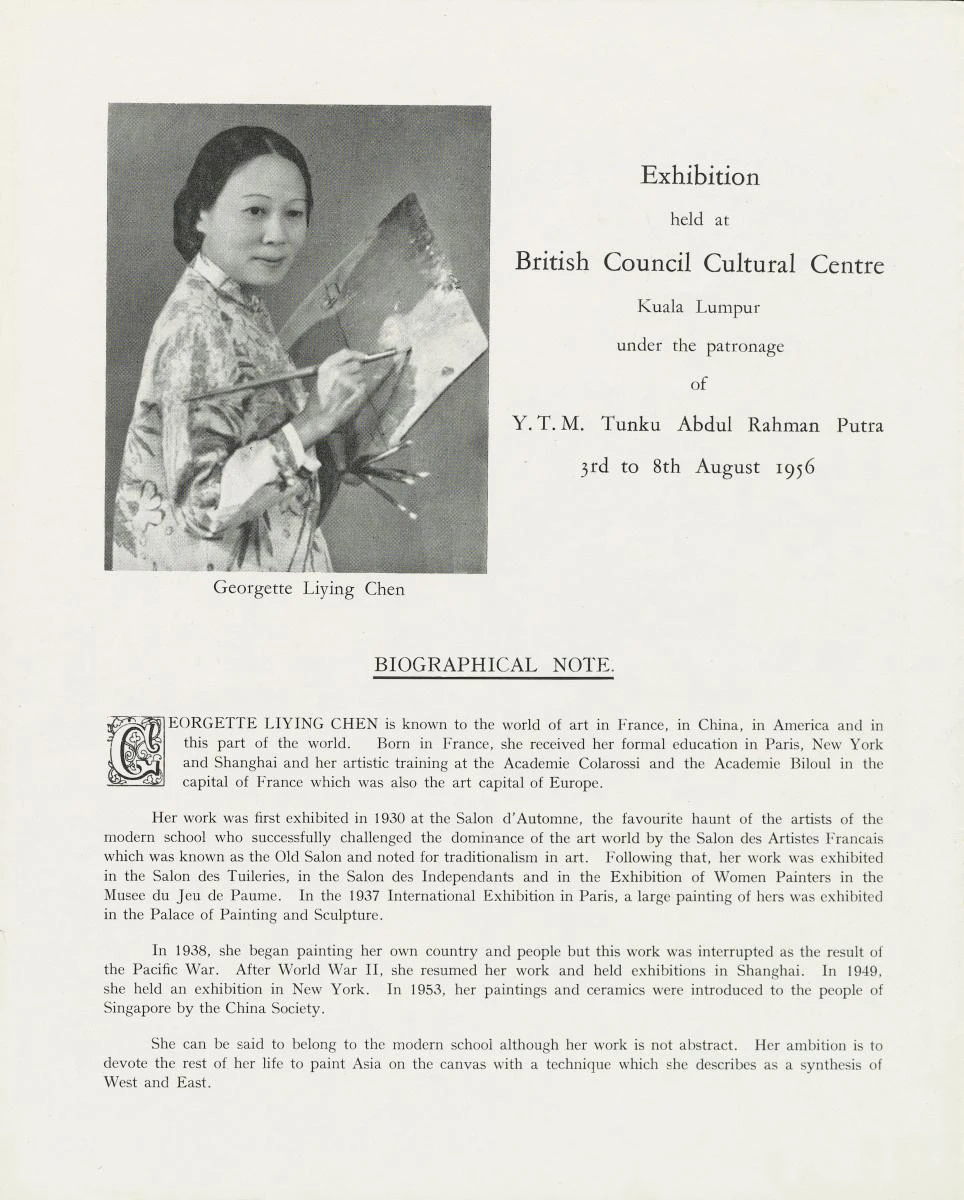

Chen’s personal effects such as her typewriter, seal, car keys, marriage certificate and passports make up a small but important part of her archives. These documents allow researchers to clarify important information such as the artist’s date and place of birth. It is interesting to note that Chen’s date and place of birth have remained a subject of debate, as her birth certificate has yet to be found and various documents record conflicting information. For example, her Singapore passports state her place of birth as China and date of birth as 17 October 1907. However, her marriage certificate to Eugene Chen states that she was born in October 1906 in Zhejiang, China. On the other hand, she registered her place and year of birth in her Singapore teacher registration form as “Paris, France” and “1906” respectively. A biographical note which she vetted for her 1953 solo exhibition in Malaya also marked her place of birth as Paris, while a manuscript of Eugene Chen’s biography, with annotations by Chen, has it as China. In a biography of Georgette Chen published by Singapore Art Museum in 1997, Jane Chia used Chen’s marriage certificate as a key source—due to its authoritative nature—to make the case that Chen was most likely born in 1906 in Zhejiang, China.3 The curators of Georgette Chen: At Home in the World revisited these documents in close detail and surmise that Chen’s birthplace is in China, with her occasional attributions to France an assertion of her identity as a cosmopolitan artist who began her career in the modern art centre of Paris. Tracing Chen’s actual birthplace and her subsequent identifications is important as they reveal multiple aspects of her identity, how she herself acknowledged these identities, and the deftness with which she moved between them.

Many of Chen’s letters were typed on this. It is currently displayed at the Rotunda Library & Archive (UOB Southeast Asia Gallery, Level 3, Supreme Court Wing).

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC.

This seal was used mainly on Chen’s ceramic works. The surname Ho references her second marriage to Ho Yung Chi.4 It is currently on display at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC.

Chen taught at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts from 1954 to 1980, where she nurtured the next generation of artists such as Rohani Ismail, Ng Eng Teng, Poon Lian, and Thomas Yeo. This document is currently on display at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC.

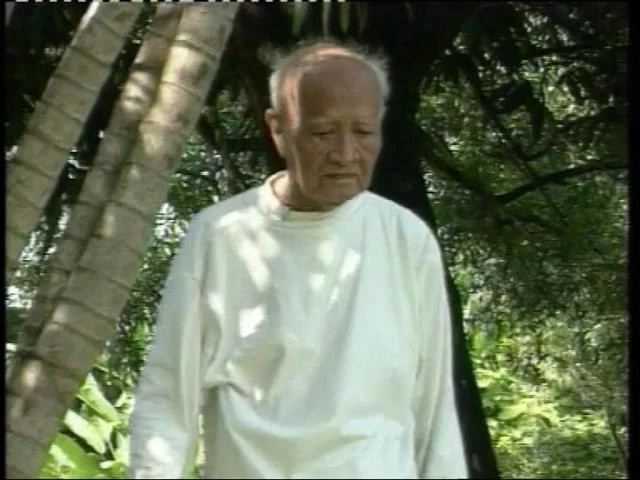

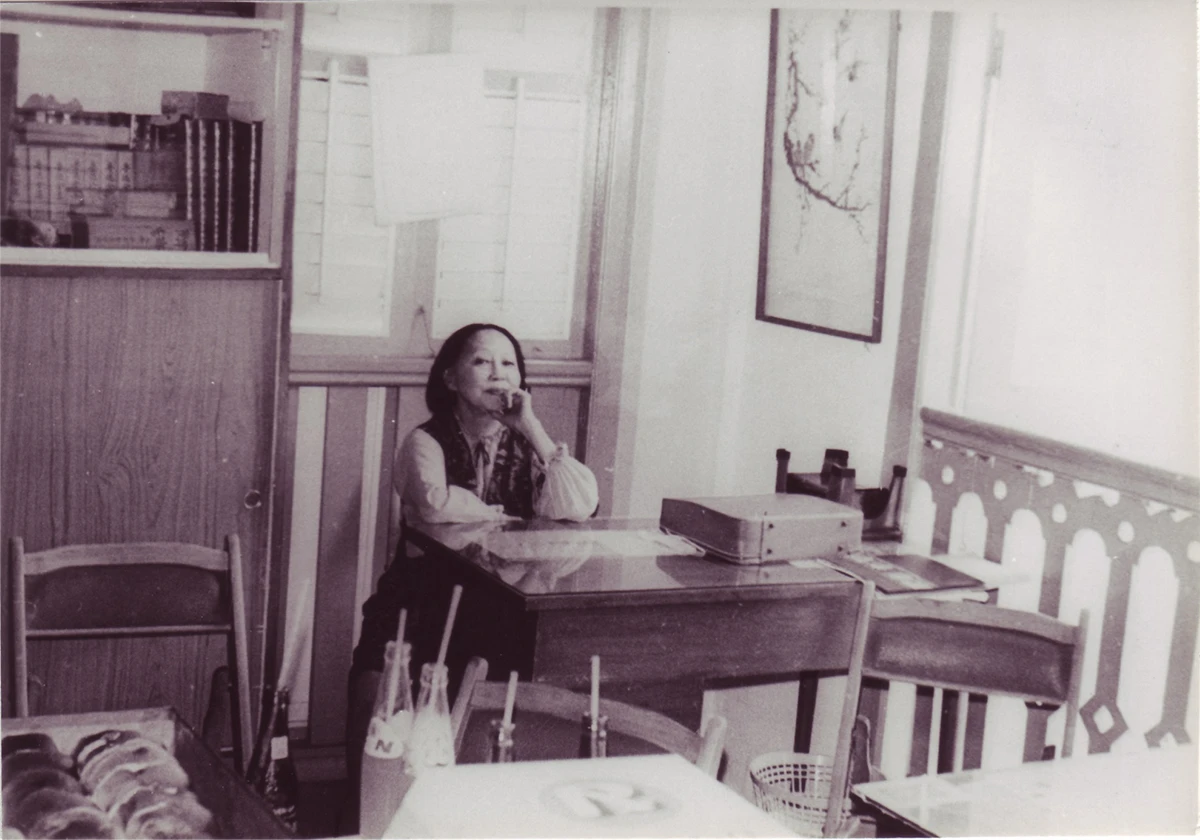

3. Photographs

Photographs of Chen painting with friends and at exhibitions capture moments of the world she lived in, and provide glimpses of the local art scene. Researchers also often use such archival photographs to verify the exhibition history, provenance and authenticity of artworks. Some of Chen’s photographs are on display in the Rotunda Library & Archive and at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition. They can also be viewed online at the Collections Search Portal.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.4.

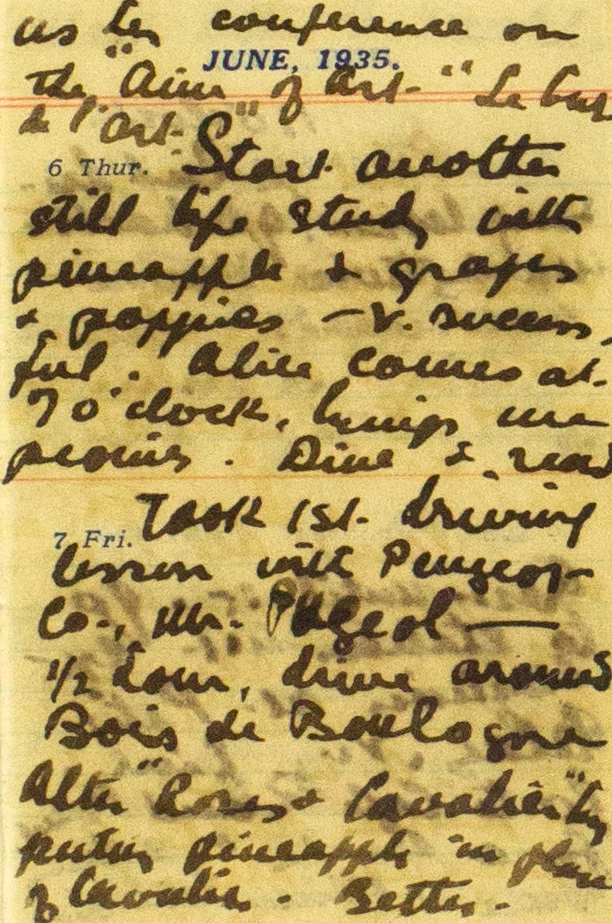

4. Diaries (1935-1981)

27 of Chen’s diaries, dating from 1935 to 1981, have survived. Written in French and English, they record her daily life and observations, such as appointments with portrait sitters, outdoor sketching trips, visits to museums, and her general feelings for the day. A diary entry on 7 June 1935 revealed that she took her first driving lesson that day, and she subsequently passed the test on 29 June 1935. She then bought a second-hand Fiat, which allowed her to drive around France to paint en plein air (outdoors). In July 1935, she drove to Aix-en-Provence, home of Paul Cézanne, where she painted at locations related to Cézanne and his paintings, such as near “Cézanne’s atelier” (diary entry, 18 July 1935), near “Cézanne’s rocks at Château Noir” (30 July 1935), and near “Cézanne’s meule” (10 August 1935), a millstone which was depicted in Cézanne’s paintings.

This diary is currently on display at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.3-01 (90 of 203).

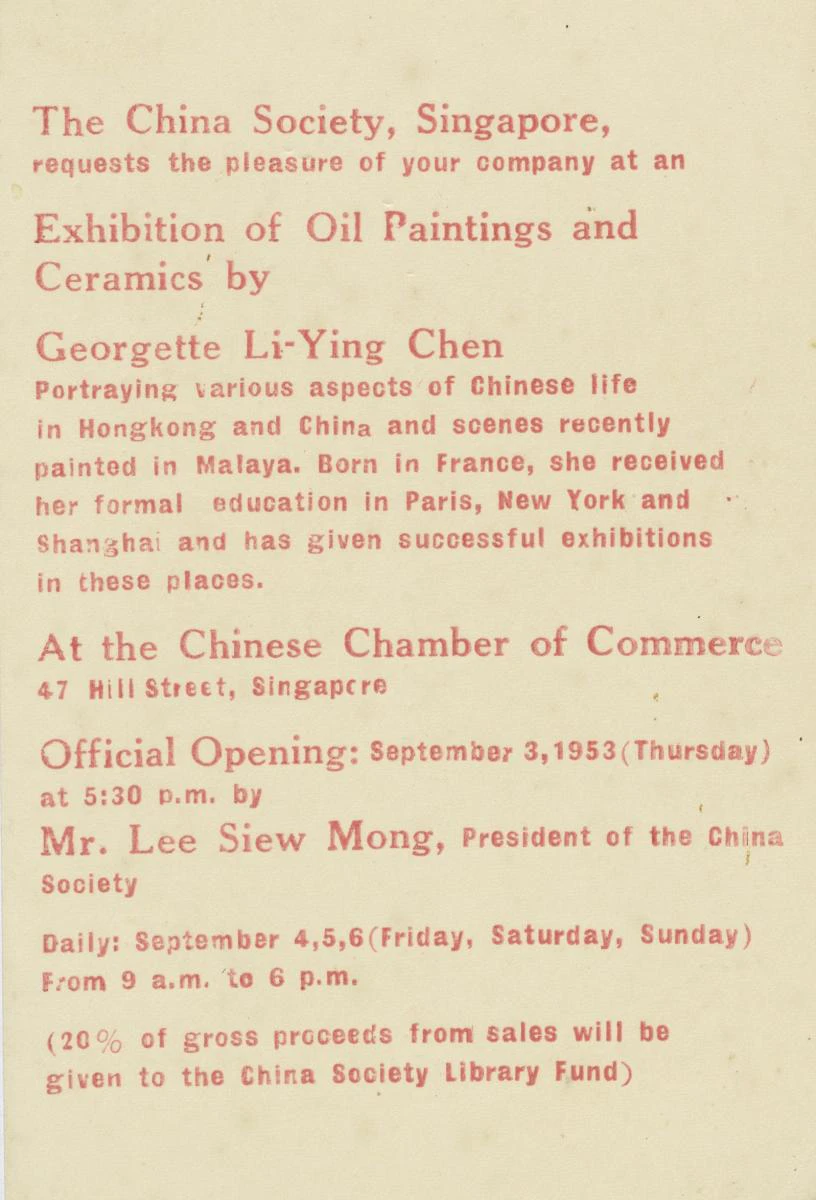

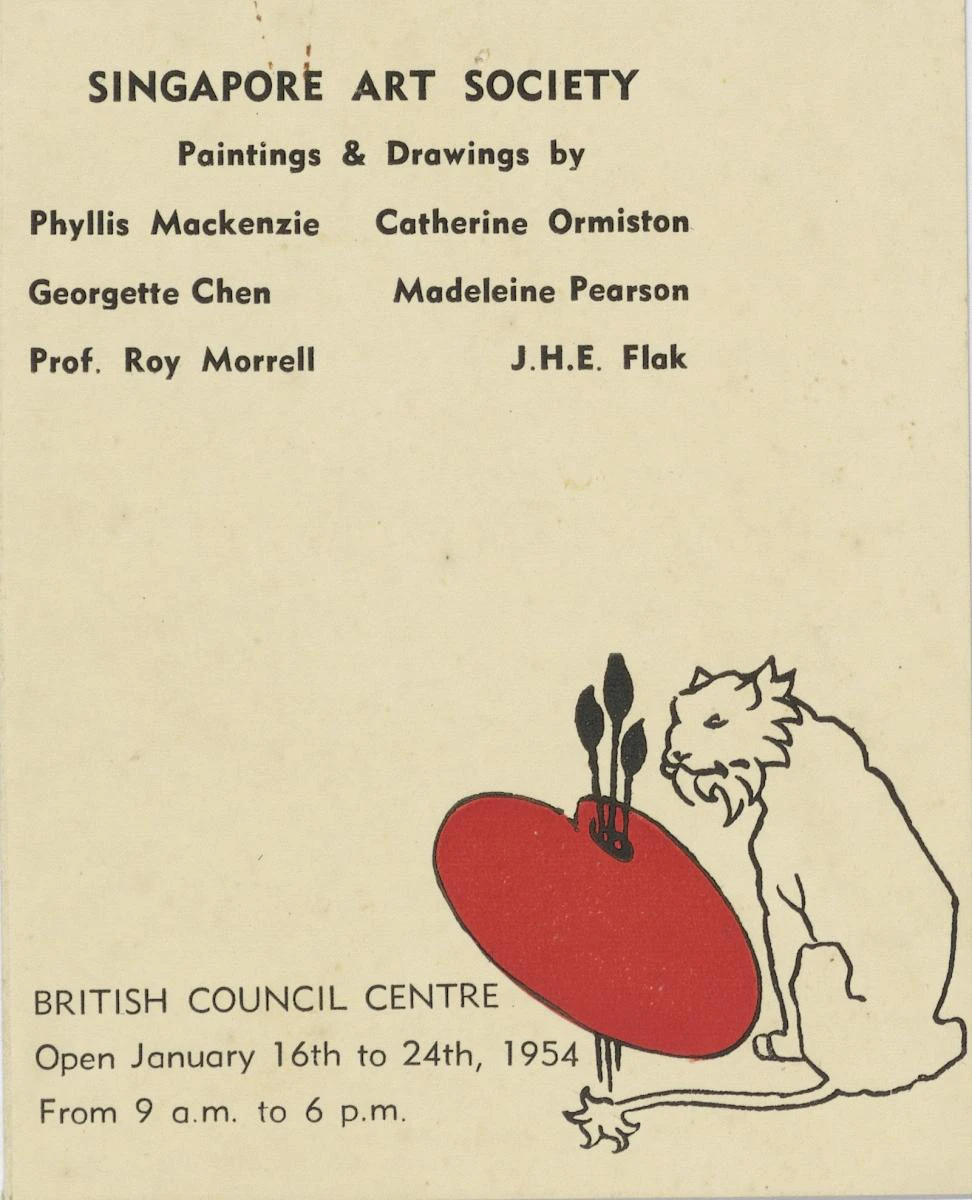

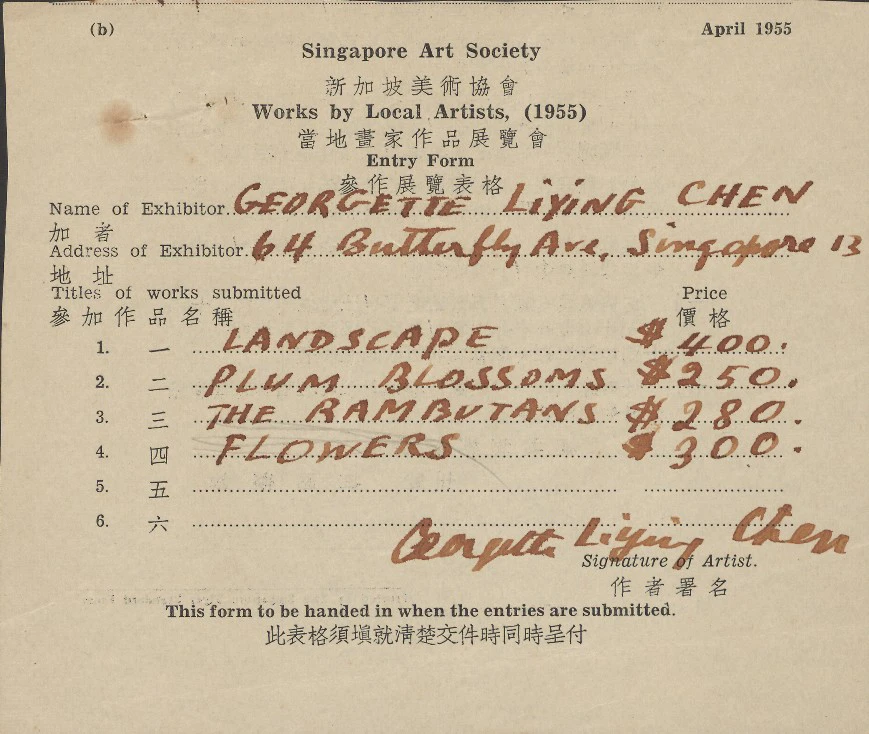

5. Documents, catalogues and invitations relating to exhibitions

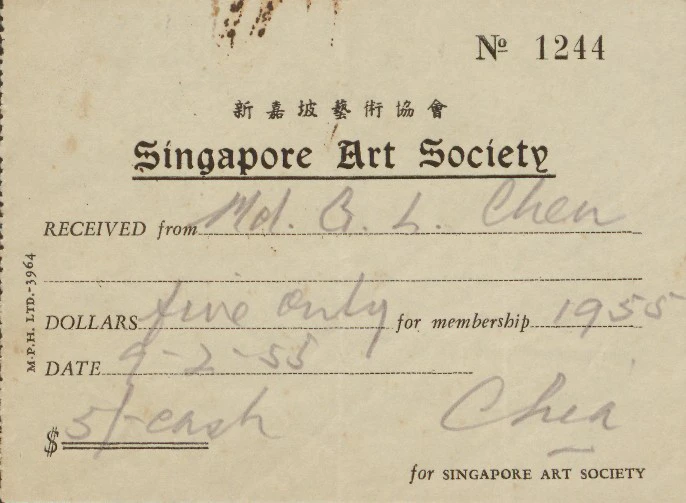

Chen actively exhibited her works, beginning from the 1930s in Paris up till the 1980s in Singapore and Malaysia. Her earliest exhibitions in Malaya in the 1950s served to introduce her as an artist to the local population. She became a member of the Singapore Art Society in 1955, which was the main platform for artists in Singapore to showcase their work at the time.

This document is currently on display at the Rotunda Library & Archive and at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.

This document is currently on display at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.7-054_0001.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.4-001_0040.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.4-001_0040.

LEARNING ABOUT THE ARTIST THROUGH ARCHIVES

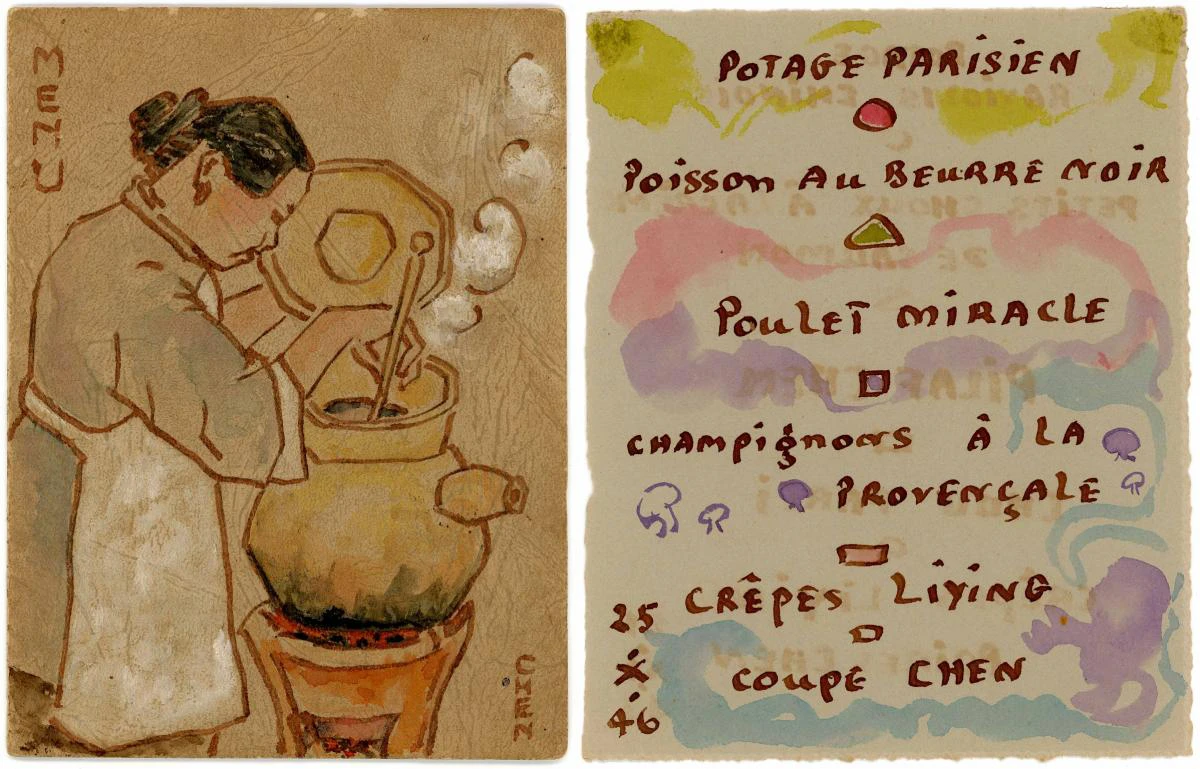

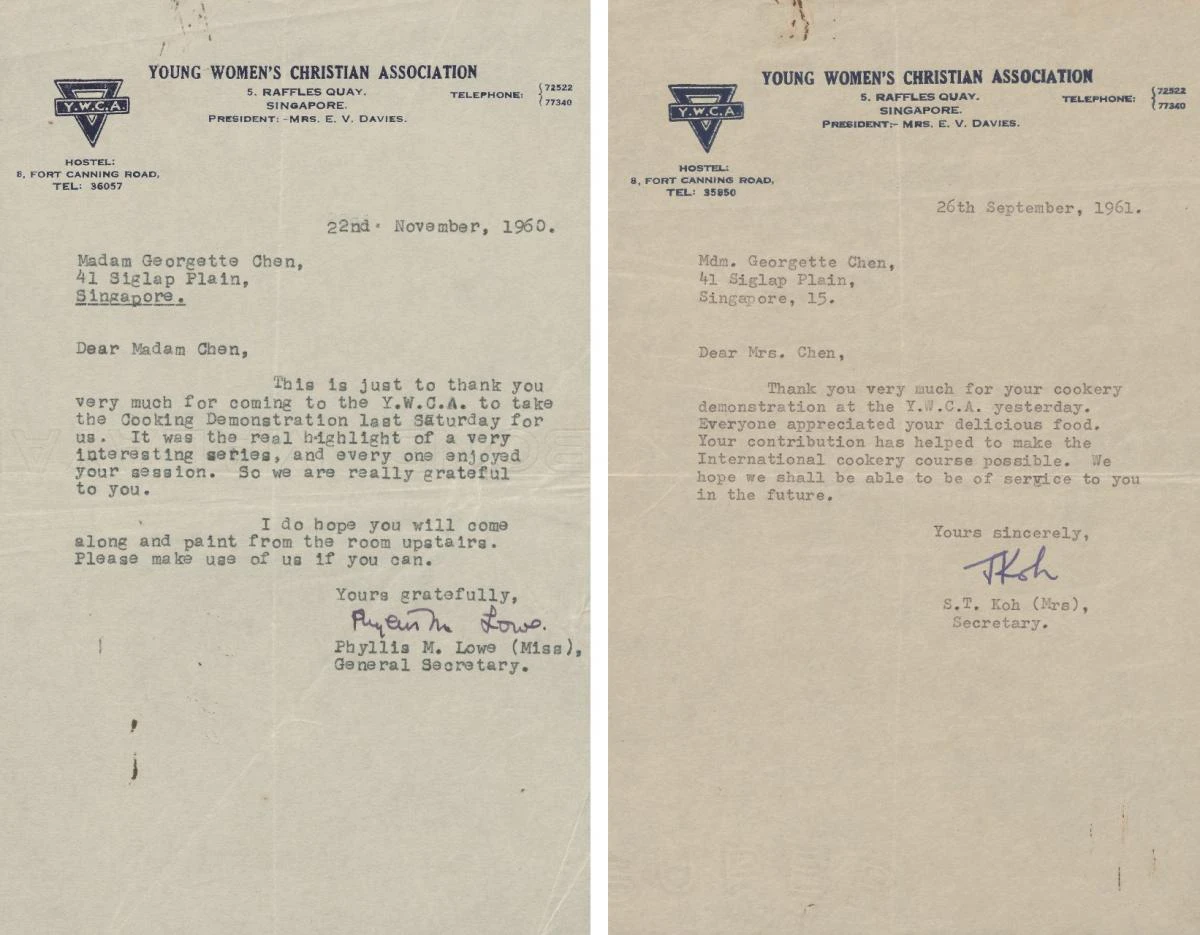

Browsing through Chen’s archives, one will realise that she had many interests besides painting, such as cooking, playing the piano, and learning languages. She was an avid cook and would organise small gatherings at her home where she would prepare food for her friends.

Cooking

Extract of a letter from Pat to Georgette Chen, dated Saturday, the 20th [year unavailable]:

It was lovely seeing you and thank you so much, dear Georgette, for that beautiful luncheon you gave Nalla and me. Your cooking is as distinguished as ever and when I look back, as I often will, I will remember the oyster soup, the fillet mignon, and the Crêpes Georgette.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive. RC-S16-GC4-1 (left), RC-S16-GC4-17 (right).

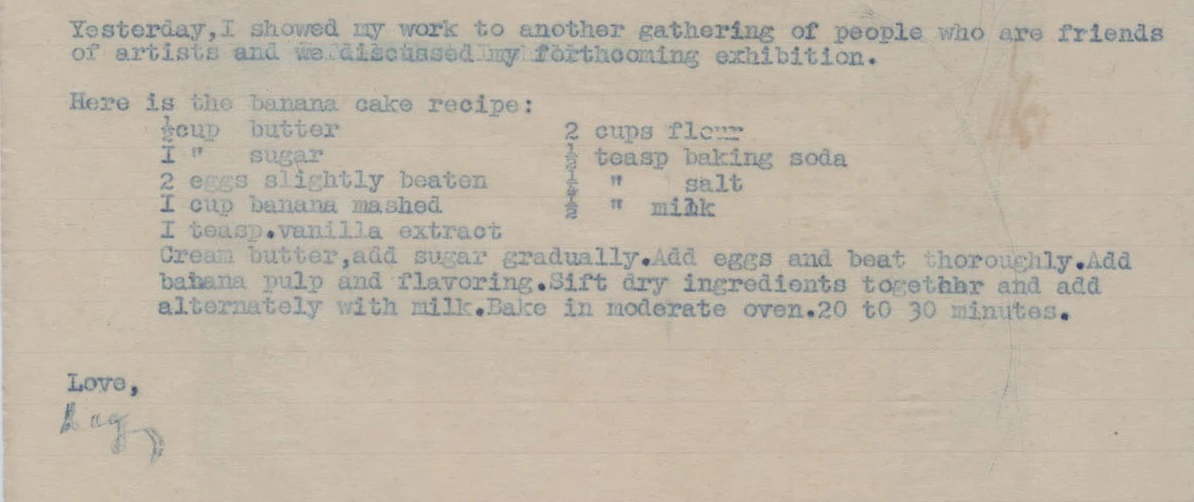

Chen’s banana cake recipe was featured in a #galleryanywhere collaboration between the Gallery’s youth programme Kolektif and local bakery The Whisking Well, who attempted to recreate the recipe. It also inspired other local bakers to try it and share their creations on social media.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.5-002_0001 (left), RC-S16-GC1.5-005_0001 (right).

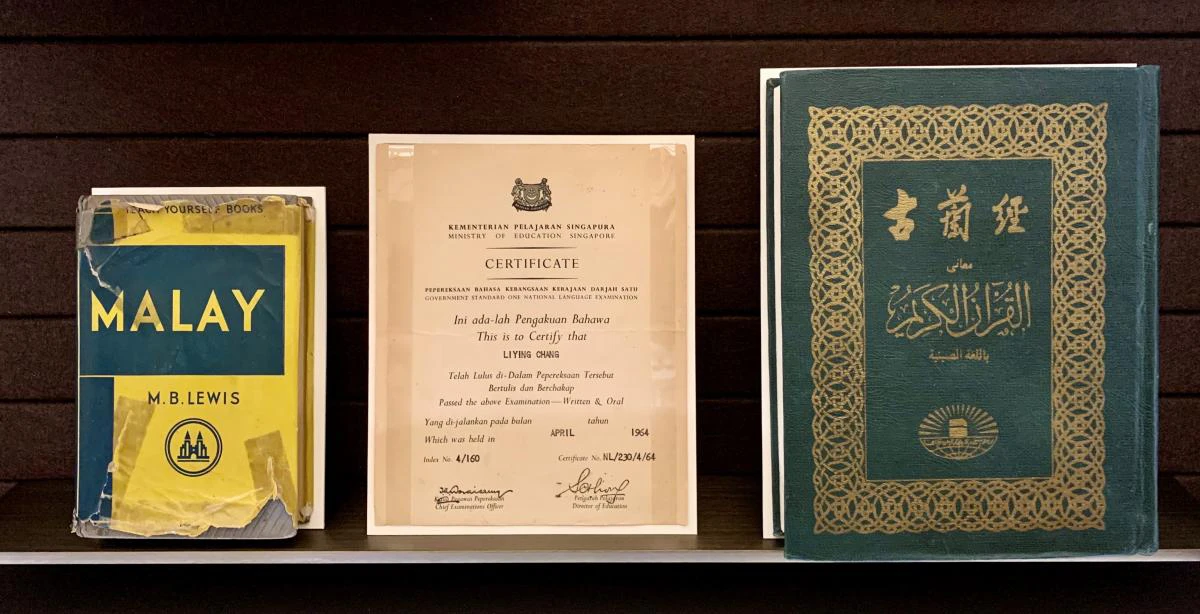

Learning languages

These artefacts attest to Chen’s interest in the Malay culture. She started learning Malay during her brief stay in Penang from 1951 to 1953, and continued her studies after moving to Singapore. These are currently on display at the Rotunda Library & Archive.

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to the Kims, August 5, 1962:

As if my existence was not full enough, I committed myself to sit for the August Malay examinations! The oral one took place on July 31st and the written on August 1st. (whole day) For three days before those dates, beginning at 6 a.m. I did nothing else but cram all that I learned, just for fun, during nearly two years and when the hour arrived, I felt as nervous as the young candidates who took part. The results will not come out until the first week of September. Pass or no, I consider it the most exciting happening for me for 1962…

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-957.

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to Yoeh Foong, January 5, 1966:

You will be glad and surprised to know that I passed that Malay exam last August and have just received a diploma for it. There is just one more diploma to get and I have started to go to adult education classes again...

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-1228.

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to Pat, June 10, 1969:

You will laugh to learn that I have just embarked on a conversation course in the Hokkien dialect! Of course I am always the oldest adult at the adult education classes! I do converse in Malay and refuse to use any other tongue with my Malay friends. I did not sit for the last standard in that language, because there are too many books to read and would encroach on my day-time programme. All these intellectual pursuits have been done in the evenings for pure fun and relaxation.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-1393.

LEARNING ABOUT ARTWORKS THROUGH ARCHIVES

Artists’ archival materials are frequently used by curators in their research. The first-hand documentation recorded in letters, sketches or photographs can help to date a painting, provide background on its subject, or serve as evidence of its authenticity.

This artwork is currently on display at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition.

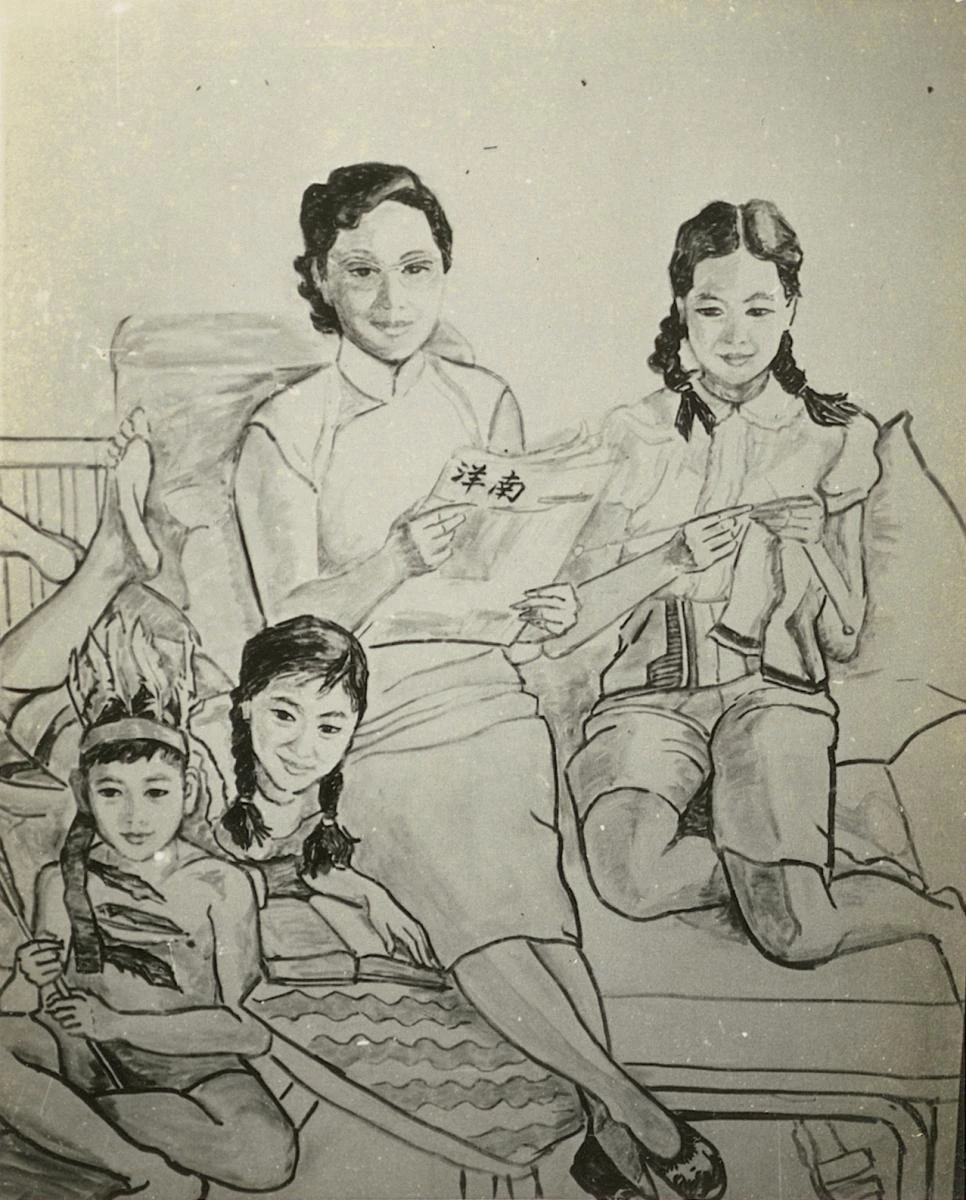

This is a portrait of the Chen family (not related to Georgette) with whom Georgette Chen was very close—Chen Fah-shin and Pauline Chen, and their children Dorothy (affectionately called Dolly), Polly and Paul (also referred to as Didi). The Chen family first stayed in Penang and later moved to Kuala Lumpur, where they continued to correspond actively with Georgette Chen. They gave Georgette Chen much support and advice during her stay in Singapore and visited each other when they could.

In 1955, Pauline and the three children visited Georgette Chen and stayed with her during the holidays. This painting was completed across several visits by the family. Below are some quotes from Georgette Chen’s letters which record the process of creating this painting:

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to Pauline, 3 May 1955:

Every minute of your stay was enjoyable for me including the tantrums and only your friendship made it possible for me to attack a large composition again, perhaps my last…I am surprised that I still have the energy to do it.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-321.

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to her friends, 30 May 1955:

The Black and White Exhibition is to open on July 20. The final receiving day for entries is fixed for the 6th of July but in the case of artists on the Selection Committee works can be sent at the zero hour which is on the day pictures are hung usually a day or two before the Exhibition opens. That means that we have two months more within which to complete “Dolly’s Family”. My vacation starts on the 9th of June and I do hope you can come down then. Everybody who comes to my studio likes your picture. Don’t forget your grey voile dress with the white and black checks.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-332.

Extract of a letter from Pauline to Georgette Chen, 1 June 1955:

We are all looking forward to meeting you soon. Can you come here for holiday? Fah-shin would like you to bring your easel and the unfinish painting too, so you can draw him here.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-334.

Extract of a letter from Dorothy to Georgette Chen, 3 June 1955:

Dear Auntie Georgette,

I heard from my mother that on the ninth of this month is your holiday. I hope you will come to K.L. You can bring your picture and draw father in.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-336.

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to her friends, 8 June 1955:

Rolling up the big canvas and taking it to KL is easy enough, but what am I to do without the easel? Without it, working will be too difficult. Besides, the whole decor (sofa cushions, etc) will be different. The best solution is still for you to try to come down and give Fahshing a rest. If you can do so say next week-end the 17th of 18th, I think my business can be finished. Then I will do my best to complete Dolly’s family.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-338.

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to her friends, 17 June 1955:

This is what I think about the big picture. The picture as it is can already be exhibited. I would like however to work in the stripes on the dress as they will make a very nice pattern. If Fashin cannot come down, I propose to send in the pictures as it is and when the whole Chen family poses for the actual painting, Daddy can be included.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-348.

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to her friends, 21 July 1955:

At 2p.m. I went to the British Council for the judging of pictures and it lasted until 6:30p.m. Yes, the big picture has been sent along with three small sketches. Now, I am so looking forward to completing the “Chen Family” in paint. One judge asked whether it was my family! It should not take too long to paint it as the “spade” work is already there. But this time it will be necessary for Fahshin to come down if he wants to occupy his rightful place as head of his family…

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-359.

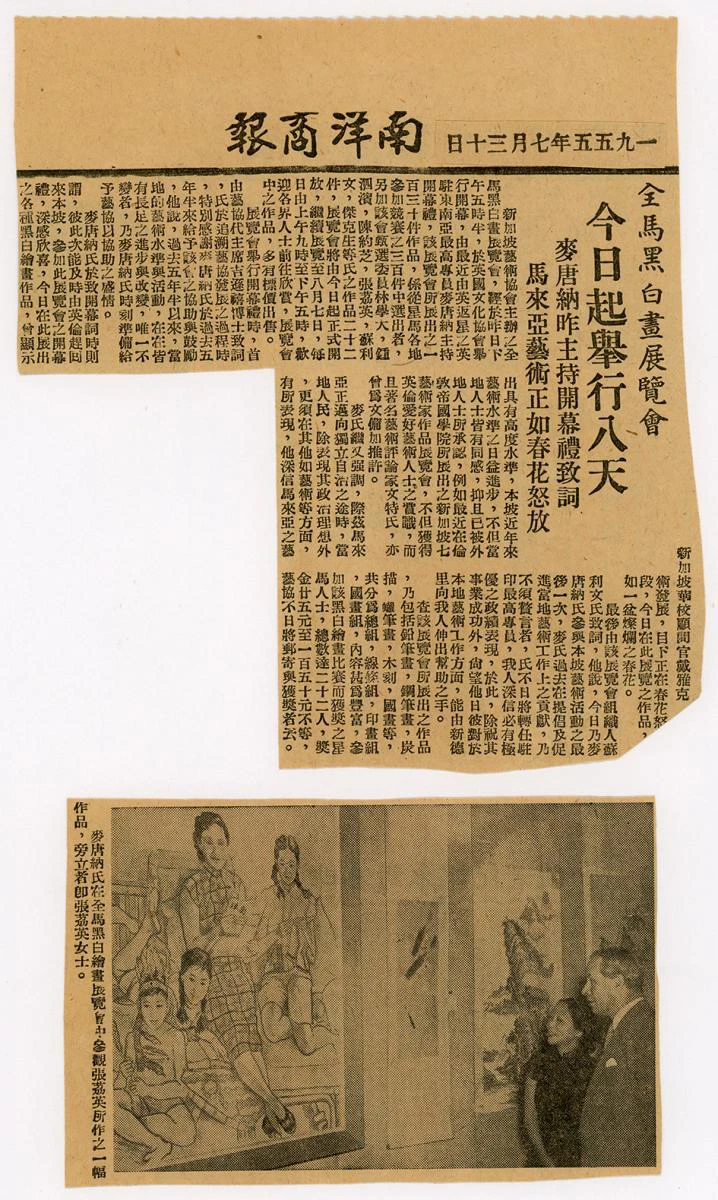

These quotes suggest that the painting was done over several sessions, when they could meet, and that the father was drawn in only later. A Nanyang Siang Pau newspaper article on the Black and White exhibition dated to 30 July 1955 indeed shows the painting without the father, as does another photograph of a sketch.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.4.

It is not clear if Chen painted another version of this painting, or if she had merely reworked it, as she mentioned the Chen family posing for an “actual painting.” There are some notable differences between the sketch and the oil work, such as the cushion next to the girl on the right (Polly) which is not in the final painting. Unfortunately, there is a gap in her letters after this period until 1956.

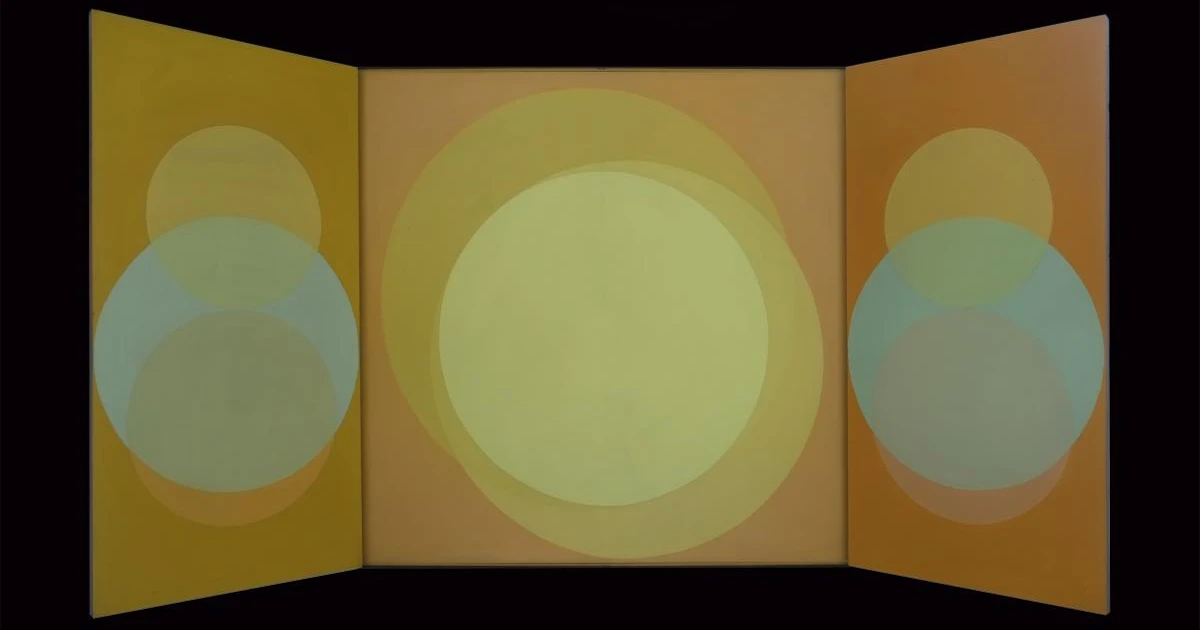

This artwork is currently on display at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition.

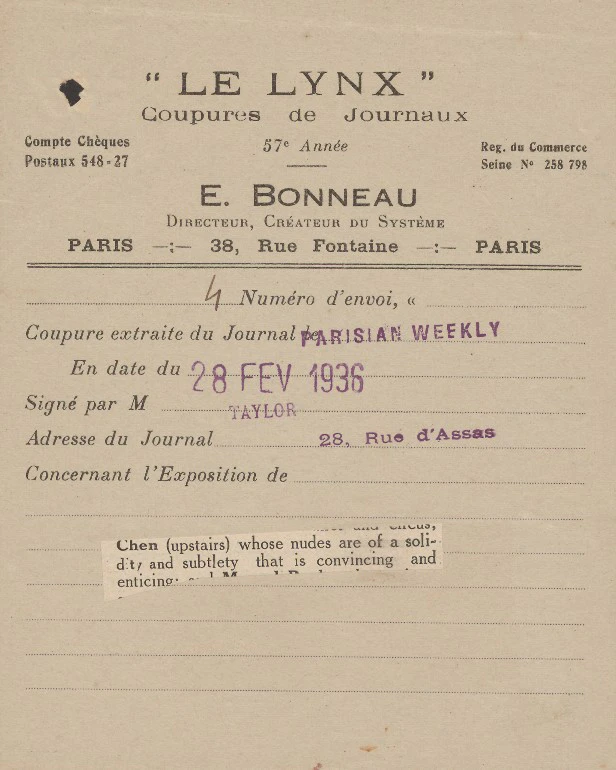

This is one of the few nude works in Chen’s oeuvre, which were mostly done during the early stages of her artistic career. Her diary details other instances when she painted nudes. For instance,on 10 November 1935, she wrote that she would “paint a big nude for the Salon”; on 14 December, she made a note to “Complete 80 F nude,” which would end up being a relatively large work about 1.46 metres high. A Parisian Weekly newspaper review dated 28 February 1936 described her nudes as “of a solidity and subtlety that is convincing and enticing.”

From Chen’s letters, one can also learn about the inspiration behind some of her paintings, and how they reflected her interests.

Local people and trades

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to Eileen, 10 December 1962:

I hope to start a large composition of a satay man. I am sure you have tasted satay when you were here last. It is the national meat dish – like barbecued beef on sticks which are dipped in a delicious curry-life sauce. The satay man cooks in front of you on his mobile stall which he carries about and it is a most picturesque subject to paint. I have asked a carpenter to make me the stall and I shall paint the picture right here in my studio. Some of my Malay students have promised to pose for me.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-1016.

Local landscapes

This artwork is currently on display at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition.

Extract of letter from Georgette Chen to Inez, 29 February 1968:

When I am not at the school, I am in my work shop abode or in my open-air work shop painting a Malay hamlet or the Singapore River, this life-line of Singapore with its many big and small sampans busily moving up and down or just lazily huddled together basking in the sun.

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-1348

Local fruits

This artwork is currently on display at the Georgette Chen: At Home in the World exhibition.

Extract of a letter from Georgette Chen to Rosamonde, 4 July 1951:

It is called the “Pearl of the East” or “Paradise of the Earth” not without reason. If Malaya does not prove to be a fruitful period for me artistically, it shall not be for the lack of beauty which seems to be everywhere… The water front with the rows of Malayan straw huts bathing right in the water whose color is green and violet, makes me shout with excitement each time I pass them by… As to the great variety of fruits, with their strange, new, and unexpected forms, they are not only wonderful to look at but delicious to eat! I have been introduced to the Durian fruit and consider that my life has been enriched by it!

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-75.

Chen was an artist who was at home in the world, having crossed continents from China to New York to Paris to Singapore, and who dedicated her artistic practice to reflecting the people and scenes she encountered at each location. Despite having experienced numerous struggles in her personal life, such as war and later health issues, she continued to express unwavering optimism in her letters. These writings underscore her determination to carve out life as a professional artist by herself, in a foreign land she had adopted as her home. This quote from a 1967 letter sums up her eventful life poignantly.

Extract of letter from Georgette Chen to Dot, May 17, 1967:

I shall be glad to leave my pictures to Singapore and Malaysia as my little contribution to this tropical land in which I have found rehabilitation. This last chapter of mine on this “treasure island’” which I call my “Tahiti” (Tahiti, as you know, is another tropical island where the French painter Gauguin adopted as his new home) has been creative and peaceful. Here, I have stood on my own two feet, albeit arthritic, and I have cut a happy coat with his colorful tropical cloth at my disposal. I have tried to pursue my work to the best of my ability, I have continued to be myself seeking neither fame nor riches. Art like love and friendship or religion is a pursuit of love and devotion. I have respected and cherished my friends and have tried hard not to take advantage of them and their love has kept me alive. Sometimes when I think that I am the product of four world events, all wars----two Chinese revolutions, the one of Dr. Sun and Mao Tse-tung and the 1st and second World Wars in all of which I have been inexorably involved, the wonder is that my profession should have been one of good-will and peace! Only God can answer for these paradoxes…..

Collection of National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive, gift of Lee Foundation. RC-S16-GC1.2-1310.

Chen’s archives can be discovered through the Gallery’s Collections Search Portal, as well as at the Rotunda Library & Archive. You can also learn more about the artist in her own words in the publication The Artist Speaks: Georgette Chen. A catalogue for the exhibition Georgette Chen: At Home in the World was also published in July 2021, and is available for purchase at The Gallery Store.

Notes

1. International Council on Archives, “Code of Ethics”. https://www.ica.org/sites/default/files/ICA_1996-09-06_code%20of%20ethics_EN.pdf, accessed on 9 December 2020.

2. Society of American Archivists, “SAA Core Values Statement and Code of Ethics”. https://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics, accessed on 9 December 2020.

3. Jane Chia, Georgette Chen. Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1997, p. 15. 000810. https://collections.nationalgallery.sg/#/details/Search/9486

4. Archival descriptions in this article have been adapted from the exhibition texts of Georgette Chen: At Home in the World.