out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19

bani haykal

out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 is a special series of creative, critical and personal responses by artists on the significance of the coronavirus to their respective contexts, written as the crisis plays out before us. From his room, bani haykal elaborates on the spaces we now find ourselves in, and the resonances they hold.

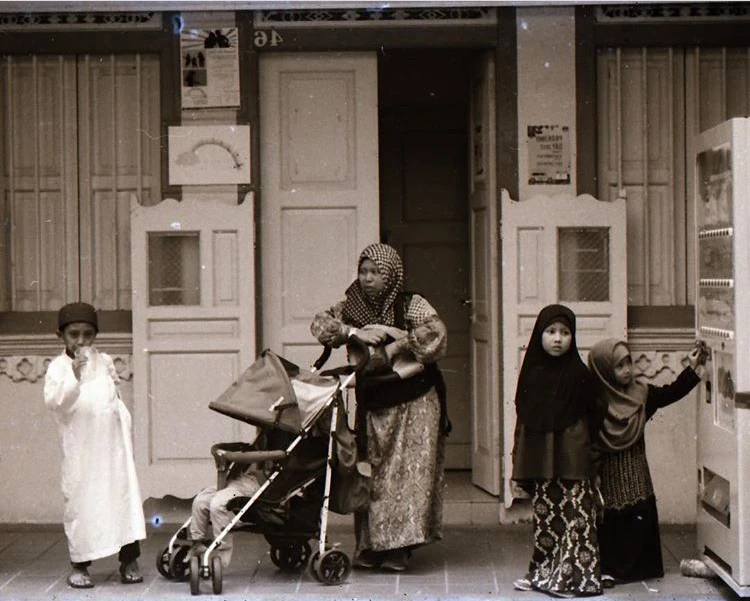

Image courtesy of bani haykal

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

For the first post in the series, bani haykal contributes his essay 'weird(er) distancing'. bani’s practice as an artist and musician considers music as material, and his practice revolves around human-machine interfaces and interaction.

weird(er) distancing

bani haykal

“I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now.”

— Alvin Lucier (1969)

“…we are all trapped inside the folds of time.”

— ila (2018)

Rooms and Resonances

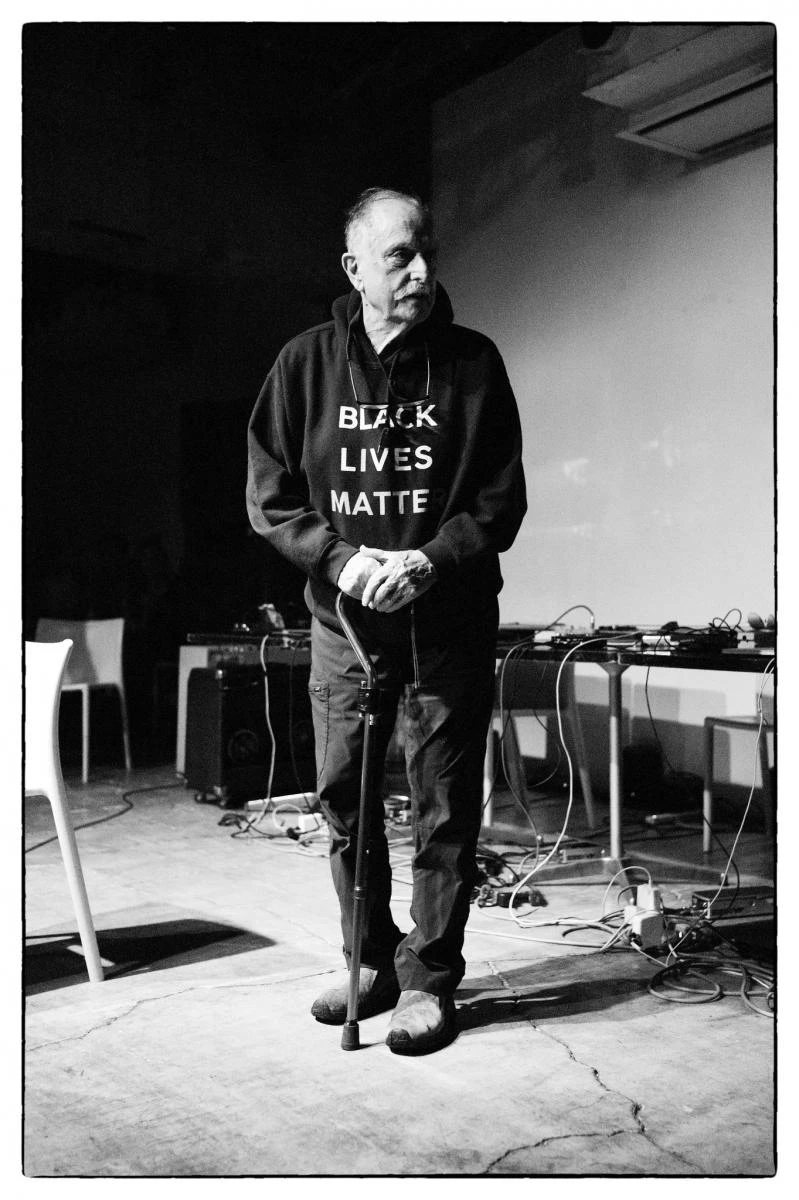

Alvin Lucier’s most popular work, I Am Sitting in a Room (1969), has been in my head ever since the circuit breaker started.1 Metaphorically though—it’s not on my playlist or something I have playing on repeat. For those who may not be familiar with this composition, it centres around a text which Lucier wrote to address the process by which his composition would take place. He read and recorded the text, which was played back into the room where it was recorded multiple times over, resulting in a degradation of the speech due to how frequencies in the recording resonates in the room.

It is best to listen to the music in full and for reference, here’s the complete text:

"I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now. I am recording the sound of my speaking voice and I am going to play it back into the room again and again until the resonant frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed. What you will hear, then, are the natural resonant frequencies of the room articulated by speech. I regard this activity not so much as a demonstration of a physical fact, but more as a way to smooth out any irregularities my speech might have."

A lot of what Lucier wrote as a score has been haunting me in how acutely it speaks to us at this point in time. “I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now,” has taken on an illustrative and representative paradigm, given the asymmetrical access/privilege to comfort, care and support that runs rampant during this incredibly disorienting time. Those who are greatly affected by the demands of having to stay at or work from home, either being subjected to domestic violence2 or not having proper and decent living spaces3, are most at risk till this pandemic is over.

If there’s one thing we recognise through Lucier’s work, it is that over time, the information transmitted by him within the confines of his own room/living space gradually disappears, or more accurately, transforms into something far more abstract.

The first element or material that Lucier experiments with explicitly is resonance. In I am Sitting in a Room, it is amplified by a subset of it known as “sympathetic resonance.”

Sympathetic resonance is when transmitted frequencies resonate with other objects that have the same resonant properties without ever being struck, much like our understanding of what it means to resonate with a particular cause that we hear of or read from someone or somewhere else. In his composition, we hear different “frequencies in Lucier’s speech cancel, others amplify, interfering with one another in a series of resonant harmonies,” as described by Marjorie Perloff and Craig Dworkin.4 The acoustic characteristics of the room Lucier is in play a crucial role in the outcome of the composition.

In other words, Lucier’s premise of being in a room different from his listeners, suggests that every room is unique, every living space is a microcosm with its own characteristics to absorb and resonate, mutating the voices within into its own abstract reality, its final outcome to be potentially perceived as noise by those outside of this room.

The second element is a crucial aspect of his experimentation—repetition. Lucier’s voice recording is still discernable on the first repetition. It is not until several cycles later that we begin to lose the fidelity of the original speech. Repetition and the “echoic interference of the room causes certain frequencies to be damped, faded and ultimately eliminated”.5 In instances such as domestic violence and squalid living conditions, repeated exposure to these circumstances or environments degrades the condition of the bodies exposed to it, and from recent events we learn, clearly, how devastating the effects can be.

Transmission, repetition and resonance in times of being "locked" in our homes stretches out towards other spaces or platforms, most prominently, social media, but the result is a different, weirder beast than in his recording. Unlike how Lucier’s speech confined to his room is “obliterated, disappearing into abstraction and pure noise,” meaning and context go through a different trajectory on social media, where obliteration produces new life cycles that bear new roots (i.e. new subtopics within the subject) and frames (i.e. context) for the way meaning and intent is reproduced.6

When our rooms begin merging with other rooms, it is almost as if worlds collide and new worlds, or "new rooms"— as I will call them—emerge. One observation I have made about social media is that a discussion or an opinion raised within the confines of one’s own room could easily merge with another and over time, such that what once felt discernable and logical to us re-presents itself as abstract material in a "new room."

‘New rooms’ where harmonic registers are far more consonant, meaning to say a room where conflict and tension is seemingly nonexistent, allude to the formation of echo chambers, where these abstract tones are musical, more pleasant and less disconcerting to everyone sharing this space. In more dissonant spaces however, individuals in these premises engage in either constructive or destructive conversations. As writer and blogger Visakan Veerasamy prompted: how do we find “points of resonance and agreement”?7

We find ourselves in these new, perhaps temporary, shared spaces where our ideas— these transmitted frequencies—clash, cancel and amplify other bits of ideas and positions, which neither room at any point prior had experienced. Whether consonant or dissonant, one thing’s for sure, we seem to be spending an awful lot of time in them. Where are we now? And what is this "new room" we are in, where our personal/private rooms, through platforms such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, are entangled?

Social media as echo chamber is only part of the revelation. What it has finally revealed is its true purpose; it is a trap!

Trapped Inside ‘New Rooms’

Being trapped in these "new rooms" with friends, strangers or strangers who later become friends (or enemies), brings to light a recent concept which emerged as a safety measure during COVID-19. It is also a concept which became the subject of reorientation. I am referring to the notion of social8 distancing9, which the World Health Organisation re-framed as physical distancing, citing a pandemic does not mean having to “disconnect from our loved ones”10. From video conferencing tools to social media platforms, little did we realise how this alternative re-connection was a trap in hiding.

The convenience of the trap during lockdown is self-evident, being homebound with little to almost zero social interactions occurring offline. For most users, the trap has become another living space. But a spike in social media engagement and going online for both socialisation and work, is the beginning of a new folding of time and space.11 Having entered this trap, we now find that several of our offline spaces have converged or collapsed to open into a "new room." Philosopher Fiona Jenkins expands on this idea of folding brilliantly through the lens of requisition, where our homes have become a “costless resource that is free of appropriation in an emergency.”12

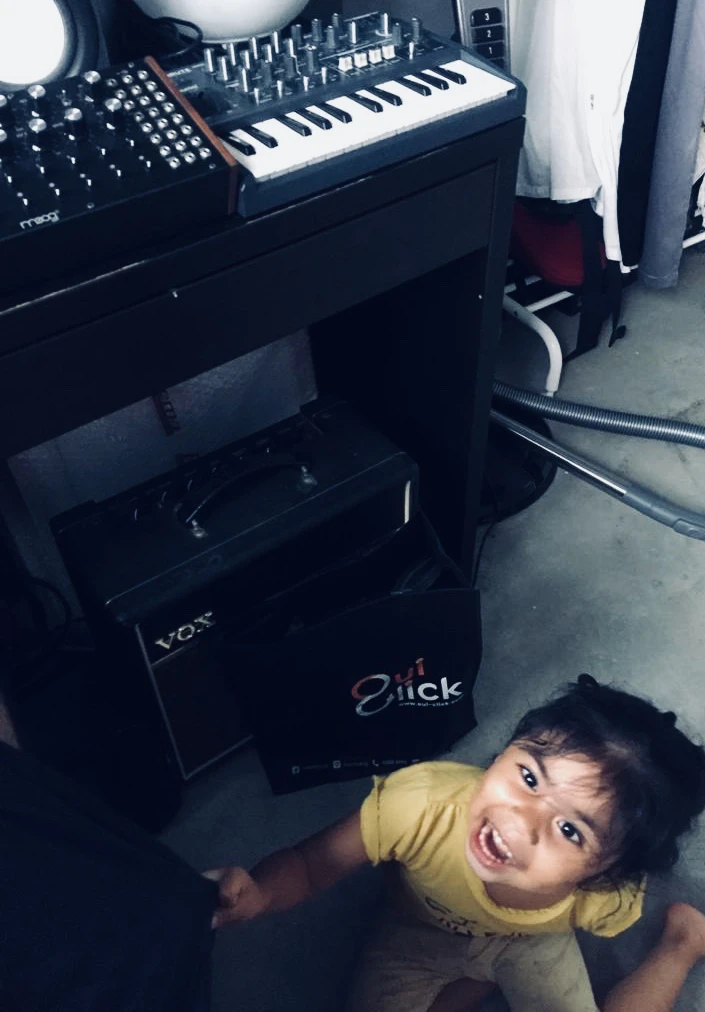

In the collapsing and folding of our offline spaces, most of us now traverse and switch roles almost instantaneously every minute of the day. My better half, ila, and I have always taken turns caring for our infinite ball of energy, our 3-year-old, Inaya. But during this lockdown, the three of us have now become colleagues. The line that separates home from work has almost disappeared, everything and everyone is condensed into this multimodal unit.

In order to break this compression of roles and spaces, we take turns bringing her out for slightly longer walks or cycling around town just to afford us some time and distance from switching roles too quickly within a short period of time, because in this new room, Inaya is inclined to constantly seek attention13, unable to discern that both of us being at home doesn’t mean we’re not bound to another time and space altogether.

Maybe it is easy for some, but this is perhaps one of the most challenging tasks in terms of navigating "new room" environments. Switching gears and hats has never been more draining because of the proximity or the melting of these once-separate spaces. Much like the emergence of "new rooms" on social media, where the rapid succession of information engages, tolerates and labours not only with abstract(ed) and contrasting views, but also amplified horrors of living through racism, these quick changes have given rise to the common proclamation of being “tired.”

In a more local context pegged exclusively to the labour involved in educating netizens on race, is the Malay word/phrase “penatlah,” originally used and expressed by poet and playwright Alfian Sa’at.14 Structures of violence are rendered invisible in online hell sites as these new rooms produce a biased form of sympathetic resonance—toxic echo chambers. Lucier’s text heralds an important premise for these repetitions, from subjects such as violence against women, queer and trans communities to racism, “smoothing” themselves out through these harmonics in echo chambers, blurring, normalising and trivialising these atrocities.

In these "new rooms," whose walls are mostly made up of hard surfaces and rigid materials, and exposure to repetition is multiplied to the point of exhaustion, it is not so much the ability to escape the trap, but to find methods of disarming them to generate other "new rooms" that provides us with ample space to engage and shift these harmonic resonances for momentary respite. This begs the question: How do we disarm with care?

To resonate with what Maya Indira Ganesh so eloquently wrote, “[t]he internet cannot fix what has been broken in society; what the internet tends to do is amplify it,”15 perhaps this is one reason why echo chambers become havens for decompression, a means of soaking in resonances during these states of repetition that are far more musical than noise. Echo chambers emerge from a desire “of self-validation, reinforcement, and polarisation of existing beliefs”[16], alongside other individuals trapped in their respective abyss of fears.

The problem of being trapped in or refusing to leave an echo chamber is that our exposure to other perspectives is reduced to an almost singular point of view. The same frequencies render other frequencies or harmonic resonances less tolerable if not dissonant. Either way, it’s still a trap!

But in times of the pandemic, for most of us our offline selves are still dislocated from this momentary virtual paradigm. We are still meatbags trapped in our newly requisitioned space, a weird, crowded place where “[t]he fridge seems to be self-emptying”17.

‘New rooms’ augment the notion of distance/distancing where everything at this given moment has never felt so close, so condensed, as if the irony of social or even physical distancing is the closing of a psychosocial gap where fears, anxieties, comfort and care are so entwined and locked in, making these experiences far more heightened than before.

Repeated exposure and repetition in this "new room" over a longer period produces different resonant frequencies, and what was once new has now become something else. In an attempt to stockpile jobs as a freelancer in the arts, where there is massive uncertainty as to what lies ahead, in this collapsed environment, this now weird room, anxieties have never felt closer.

Video conferencing or expressing myself on social media—any attempt to close the social and physical distance—isn’t at all a fix for this sensation. This is an almost unnamable weirding. Social distancing now feels like a metaphorical bridge that takes us towards a different horizon, one where we will live in crisis mode in perpetuity. The crossover of "new rooms" gives rise to the birth of "weird rooms," perhaps meant to be a place of dwelling where we may envision being comfortable in the “new normal”18.

In these very unpredictable and uncertain times, where are we going? What would residing and living in these rooms over an extended period of time feel like? And most importantly, how long more will we have to be in them?

Time Traveling / "Weird Rooms"

In this "weird room," everything feels like it is happening concurrently. Did we get here by accident? Or is this a feature of the new normal? Did we allocate enough time, space, or literally enough distance, to contemplate what and where new paths should go in the name of “normalcy”? There is a rush, a rush to stop a pandemic and not a failing system, and it all feels horrifying. Where are we right now?

Being inside this ‘weird room’ is like being online and offline constantly. There seems to be no pause or space— maybe it is best described as a weird sense of distances/distancing. It feels like breathing in two different spaces at the same time. And even if I were to step out of this room, the room follows me still. This is perhaps the smoothening out of the irregularities in "new rooms," a space where resonant frequencies have shifted from echoes to one self-oscillating reverberation. "Weird rooms" can be seen as a dimension of constant drones, where time feels as if it were at a standstill.

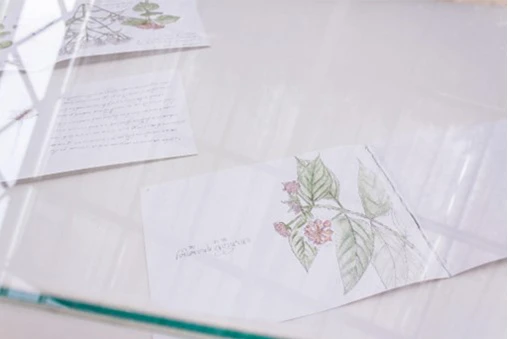

Here I am inspired and struck by ila’s short fiction, quoted in the opening of this text. The line is taken from her series of speculative fiction called Pura-Pura Parade.19 These works are accompanied by photographs she’s taken over the course of her practice wherein she makes sketches from photos. It is fitting to include the entire piece here:

“we do not need time machines. time mischievously fold inside itself, hiding the present from the past under the guise of linearity where moving forward is upwards and looking back is backward. in actuality, we are all trapped inside the folds of time.”

Time travel is a useful analogy for how we’ll survive and live in these ‘weird rooms’ of unnamable or unnamed realities, where this enlivened messy environment is rich with new threads, links and stories to weave. If "new rooms" introduce us to new resonances and repetitions, ‘weird rooms’ induct these resonances and repetitions, turning our relationship with them into loops. A "weird room" is a world where we are all time travelers, where paradoxes and plot holes are required tools to jump not only between time and spaces, but to alter, write and weird realities in these loops.

Unlike the desire “to treat the past as material to be transformed and augmented to create a future”20, ila’s framing of time travel by rejecting the time machine is centered around the reorientation of time and space into what Ben Woodard has called “intelligence as time manipulation”21. This is a form of reorientation that is specific to enacting change for the present, such that even speculation about the future is material for altering this very moment.

We are now in rooms where we’ve grown perhaps immune to their claustrophobic effect, being required to remain productive, to keep a system running and propel towards new, virtual environments, a further squashing of space to conform or lock in to more gridded and isolating structures, with tools some of us have yet to fully comprehend.

We are living through a collapse, and the exit is temporarily out of order. "Weird rooms" might be the moments we find loopholes in each recursion, discovering new paths and pieces for us to slip through. When everything is so close and distance is not an option, we might have to listen to the same granular tones crackling in drones over and over again before we can recognise the harmonic resonances of the room and where or how we can augment it. I return to a previous question posed on the premise of ‘new rooms’, albeit an augmented version of it: how do we dwell in this seemingly infinite loop with care?

The new normal will be a loop of exiting this limbo of infinite resonance, where the walls reflecting these ongoing frequencies say more about our trappings than our imaginings of where we want to go next. Post-pandemic spaces and frontiers should strive for a fluid and interchangeable normalcy, rejecting the hard, rigid surfaces which have hosted our long-staying nightmares from the previous “normal.”

Maybe in this next “normal,” natural resonant frequencies will shift based on the dynamics of those inhabiting the space. In light of the possibility that a vaccine might never emerge, or that it may be years before one is developed22 and widely distributed, if our next “normal” is built on the premise of softer and more intimate negotiations of space, I think we might be able to live and thrive in this "weird room."

Acknowledgements

Thank you first and foremost to Joleen Loh for the invitation to write this as part of the magazine, I absolutely appreciate the opportunity! Thank you also to Joyce Choong for help with editing the piece, it’s been a very pleasant process of realising this. Thank you also to Fabio Lugaro for responding on Twitter promptly for his photograph of Alvin Lucier!

I’d like to express infinite love and gratitude to my fellow road trippers, ila + Inaya + Shawn, who’ve been absolutely generous and supportive as always. I am indebted to the labour they put in, helping to thread through, piece together and also challenge some initial positions taken for this piece. This really felt like a road trip!

Notes

- Circuit breaker refers to stricter measures taken by the Singapore government, likened to a lockdown, during the COVID-19 pandemic, see: “PM Lee Hsien Loong on the COVID-19 situation in Singapore on 3 April 2020,” Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, Apr 3, 2020, https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/PM-Lee-Hsien-Loong-on-the-COVID19-situation-in-Singapore-on-3-April-2020.

- For statistics regarding violence against women and girls, see: “The Shadow Pandemic: Violence Against Women and Girls and COVID-19,” UN Women, 2019, https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/issue-brief-covid-19-and-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls-infographic-en.pdf?la=en&vs=5348

- Rebecca Ratcliffe, “'We’re in a prison': Singapore's migrant workers suffer as Covid-19 surges back,” The Guardian, April 23, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/singapore-million-migrant-workers-suffer-as-covid-19-surges-back.

- Marjorie Perloff and Craig Dworkin, The Sound of Poetry / The Poetry of Sound (University of Chicago Press, 2015), 169.

- Ibid, 169.

- Lina Dzuverovic, “On Not Accepting the Forgetting,” http://www.dzuverovic.org/?path=/texts/on-not-accepting-the-forgetting/.

- Visakan Veerasamy, Twitter post, May 30, 2020, https://twitter.com/visakanv/status/1266522047129071617?s=20.

- It is worth pointing out that Singapore shifted their phrasing to ‘safe distancing’, see: “Advisory on safe distancing measures at the workplace,” last modified Mar 26, 2020, https://www.mom.gov.sg/covid-19/advisory-on-safe-distancing-measures.

- Choo Yun Ting, “Coronavirus: Singapore mindful of need to calibrate social distancing measures, says Lawrence Wong,” The Straits Times, Mar 11, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/spore-mindful-of-need-to-calibrate-social-distancing-measures.

- Emphasis on physical distancing was made to prevent increased exposure to the virus, see: “WHO Emergency Coronavirus Press Conference Transcript,” Mar 20, 2020, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/transcripts/who-audio-emergencies-coronavirus-press-conference-full-20mar2020.pdf?sfvrsn=1eafbff_0.

- Anuradha Rao, “Commentary: It’s not just work and the economy. COVID-19 is also changing how we use social media,” Channel News Asia, Apr 14, 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/covid-19-coronavirus-has-changed-social-media-use-12636682.

- Fiona Jenkins, “Did our employers just requisition our homes?,” The Canberra Times, Apr 4, 2020, https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6701054/did-our-employers-just-requisition-our-homes/#gsc.tab=0.

- We love you Inaya and we enjoy every post-apocalyptic adventure with you :-)

- Penat is Malay which means tired, to have the suffix “lah” attached is often to denote a form of resignation, as Alfian puts it, "[a] resignation beyond sorrow”. See: Alfian Sa’at, “I'm actually starting to feel unsafe just existing as a minority in Singapore.,” Facebook, July 31, 2019, https://www.facebook.com/alfiansaat/posts/10156608389667371.

- Maya Indira Ganesh, “Between Flesh: Tech Degrees of Separation,” 13th Gwangju Biennale – Minds Rising Spirits Tuning, https://13thgwangjubiennale.org/minds-rising/ganesh/.

- Tal Orian Harel, Jessica Katz Jameson and Ifar Maoz, “The Normalization of Hatred: Identity, Affective Polarization, and Dehumanization on Facebook in the Context of Intractable Political Conflict,” Social Media + Society (2020), 9.

- Fiona Jenkins, op. cit., Apr 4, 2020.

- Salma Khalik, “Coronavirus: Expect a new normal even if current circuit breaker measures are eased,” The Straits Times, May 7, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/expect-a-new-normal-even-if-current-measures-are-eased.

- Pura-Pura is a wordplay off Singapura, of which “pura-pura” in Malay means to pretend or, in this context, a ‘pretend-parade,’ or a parade of pretense.

- Ben Woodard, “Loops of Augmentation: Bootstrapping, Time Travel, and Consequent Futures,” in Augmented Intelligence Traumas, ed. Matteo Pasquinelli (Meson Press, 2015), 162.

- Ibid, 158.

- Carrie Arnold, “Why it’ll still be a long time before we get a coronavirus vaccine,” New Scientist, Apr 29, 2020, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg24632804-000-why-itll-still-be-a-long-time-before-we-get-a-coronavirus-vaccine/.