Life as Art: Collecting with Chua Soo Bin

Chua Soo Bin is not only a renowned photographer, gallerist, art dealer and art patron, but also an avid collector of culture and history. Over a casual chat with his favourite cheesecake and freshly brewed coffee, Chua shared some of his favourite items from his personal collection, as well as his life and collecting philosophies.

Chua Soo Bin is not only a renowned photographer, gallerist, art dealer and art patron, but also an avid collector of culture and history. Over a casual chat with his favourite cheesecake and freshly brewed coffee, Chua shared some of his favourite items from his personal collection, as well as his life and collecting philosophies.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

As a photographer yourself, do you have any favourites among the photographs that you have collected?

When it comes to photography, portraits are my favourite. I like to photograph people, and enjoy looking at portraits as well. In my own work, I am very particular when it comes to detail, and can take a few months to take a single shot. My photographic project Legends was about capturing portraits too. For that project, I chose to include aspects of the subjects’ personal lives when I took those portraits so they would be more moving (深动一点).

One of the photographers I look up to the most, one of my all-time favourites, is Yousuf Karsh.

This is an iconic photograph of Winston Churchill by Yousuf Karsh taken in 1941, considered to be one of the most widely reproduced images in the history of photography. How did you come to own this photograph?

I bought this at an auction in the 1970s or 1980s. It is a very rare photograph. When this was taken in 1941, Churchill was always with a cigar. Right before taking this photo, Karsh personally removed the cigar from Churchill’s mouth and took this shot of a resultantly scowling Churchill.

I really respect Karsh and his work and am very fortunate to have this photograph. This photograph was on the cover of the auction book when I bought it. I think it cost about 70,000 renminbi (approx. SGD13,800). The price was quite high for that period as there was a lot of interest in it.

I also have a photograph taken by a photographer whom I deeply admire, Henri Cartier-Bresson of the Magnum Photo group. I bought the photograph at an auction too.

A group of Magnum photographers came to Singapore... I cannot remember when. Three or four of them were here. I had lunch with them and brought them around to shoot in Chinatown. They left a very deep impression on me, thus I am able to remember it vividly even now. If you were to ask me in a few more years, I might not remember as well!

They wanted to visit the death houses along Sago Lane. These were the places where people took their last breath. I took some photographs myself. They later prohibited photography in these death houses. Only Singapore had such houses. The Magnum group liked shooting such subjects.

Many of the Magnum photographers whose works I like have already passed on. They had a huge impact on my photographic practice. The Magnum group never used additional lights when taking photos, only natural light. I also heard that when they sent their film to the office lab, they did not allow any cropping. They were very particular about such things. They took a lot of war photographs, which I really like. There is no special reason.

What were some other significant influences on your photographic practice over the years?

I never went to school to study or train in photography. I started out by working in an agency. Photography started as a hobby for me, and then it turned into a career.

While working in agencies, I got to work with well-known photographers from Australia and Japan on large projects, assisting them and learning from them – from how to take photographs to how to set up each shot. Sometimes, the preparation for a shoot did not merely involve setting things up in a small corner, but rather involved a big set-up that the photographers could move around in to take photos from different angles.

I was greatly influenced by Japanese photographers. Some of them came to Singapore to shoot several projects, and I also went to Japan to visit them and their studios.

What was it about Japanese photographers that you admired?

There was something that left a particularly deep impression on me. I knew a Japanese photographer who was assigned to shoot a building. We think of a building as something that is already so stable. But for this photographer, he wanted to wait until night time when all the air-conditioning was turned off and everyone had left before taking the photo of the building. This was to minimise any vibration whatsoever.

Taking photos then was very different. It involved using film and big cameras, which would have to be held very still, and sometimes for very long exposure times. The Japanese photographers I knew were very particular about these things. I really respect them for this reason. This is also why I have a lot of Japanese friends.

What about your experience with photographers from Australia?

My experience with Australian photographers was in tourism shots. I went to Sydney to work with them. I learnt how to be a professional photographer from them. I even learnt how to shoot a glass of beer. The ice was all fake, bought from Japan. It looked like real ice but was fake and would not melt. A lot of people did not know this. I still have the ice!

How was shooting back then different from shooting now?

Back then, when I was shooting, many ladies requested for soft focus. What I did was breathe out on my camera lens and allow the condensation to gradually dissipate, creating a naturally soft effect. There are a lot of these tricks.

Now, photography is so different from what it was like in the past. Now everything can be digital, and you can edit the photographs with many different effects on a computer. There was no such thing last time. When we took a photograph, we had no idea what the final shot would look like until we developed it. So we were very careful. We even had to count the number of seconds manually. It was not easy, for example, measuring things like depth of field.

My first camera was a Rolleiflex. I still keep my old cameras. I have given some to my son. He still uses them after adding a digital back to the camera.

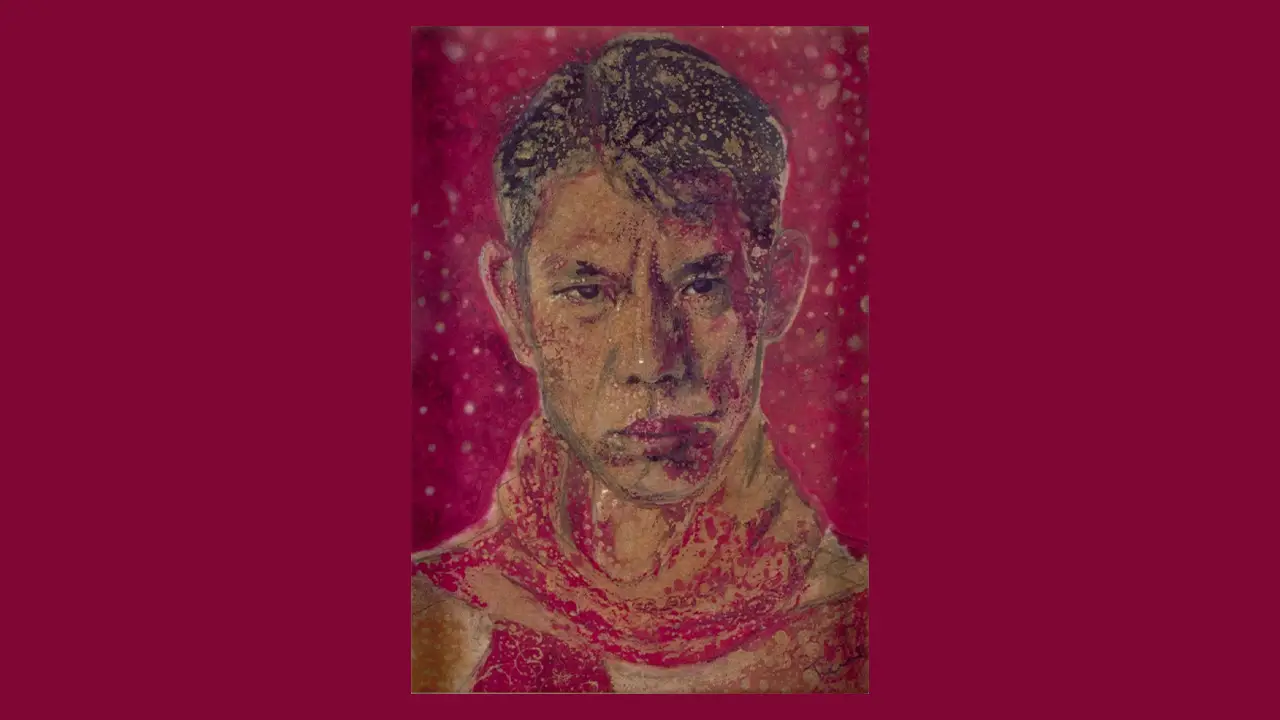

You have a lot of Vincent Leow’s sculptures in your home. How did you get to know Vincent?

The faces of these sculptures are self-portraits of Vincent himself; did you know that?

Vincent came to look for me when he was selected to represent Singapore at the Venice Biennale in 2007. I was in Chengdu (China) at the time and was acquainted with people working in a stainless steel factory. I decided to support him and arranged for him to come to Chengdu to create his works, all expenses paid. I went to Venice to see the exhibition too.

During the production process, we decided to make two of each sculpture, which is why I have so many of them. I put them in my garden because my warehouses are all full. I have even more of them in China. They are very bulky and take up a lot of space, they are also made of stainless steel and so can withstand the rain and heat.

Why did you decide to support him?

I think Vincent is an excellent artist. He is a good friend too. I am a big fan of his work and I really support him. It is nothing much. As artists, we promote art, including the art of other artists. Sometimes we make money, sometimes we make a loss. It is a choice I make to support many artists.

I also have a few of Vincent’s earlier works that he made in the US. I bought two big pieces. I go to see all his exhibitions and buy a lot of his pieces. It is very important to support local artists. I know because I own a gallery. Some artists make money, some artists do not. Some artists, even though they are good, do not make money, but should be supported. I do not like artists who make money. <laughs>

You collect so many different things, from photographs and sculptures to pottery and puppets. How do you decide what to collect?

I collect a lot of things. Except money. <laughs>

I feel culture and history are worth collecting. By collecting these things, I am collecting a piece of culture, I am collecting a piece of history.

This is my hobby. I do not buy very expensive things. I think people should keep what is important to them, things that hold memories, that have sentimental value, or even just things they like. These are things that money cannot buy.

One thing about me is that I tend to dislike things that other people like. I do not want to be the same as everybody else. I like to be different, though not intentionally. I just look at things from a different angle. I pursue a different kind of beauty – the imperfect, the damaged (残).

Like these pots from the Song Dynasty. I purposely chose all the pots with imperfections, beautiful in their own natural way. Time too is a brush. It naturally leaves its mark. 时间是一种画笔。

I have kept these puppets for over 20 years. I bought them from a flea market when I was in Chengdu, just because I thought they were quite fun. They are old, wearing clothes that are tattered and torn. I think they are great.

Many people are frightened when they see these puppets, but I like them.

These pipes are all antiques and are hard to find. I use a few of them myself.

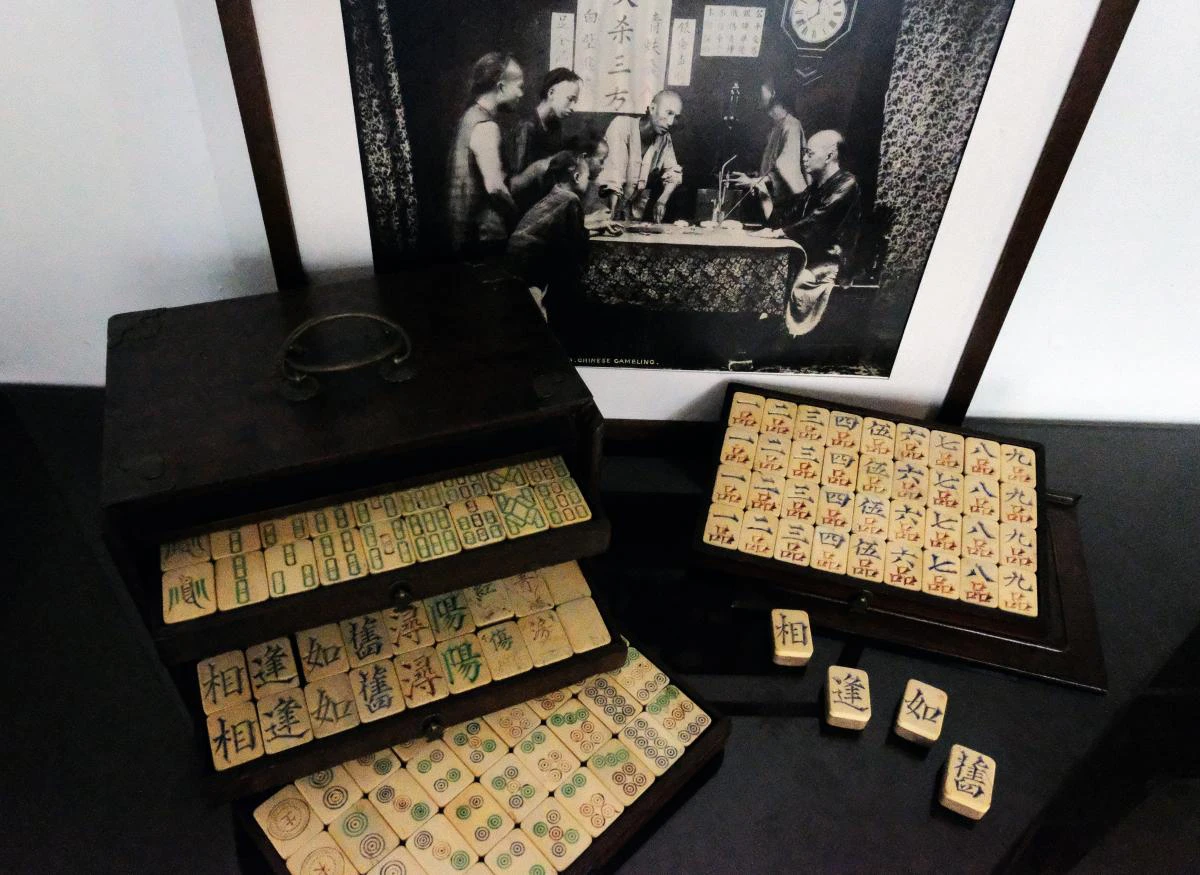

This is a very rare mahjong set. The tiles are made of ivory. There is a mahjong museum in Ningbo (China) that does not have a set like this.

I used to play mahjong often but stopped because I was not very good at it and kept losing. <laughs>

The rectangular brick is actually a piece of a coffin. I was doing commercial work and got sent to Pakistan for a job in the 1970s. There, stone coffins fill the mountains, instead of being buried underground.

I had wanted to buy a stone coffin before, but it was very big, and I would not have had a place to put it.

Some people might be afraid, but I am not. They say coffins help to bring about wealth (棺材是一种财,会发财)!

This bronze monkey head is a replica of the original made by Lang Shining in the Qing Dynasty, which was part of a fountain featuring 12 zodiac statues. The 12 original heads were lost and sold all over world, but are now being bought back by China as part of their cultural heritage.

The original bronze monkey head belongs to the Poly Art Museum in Beijing. I obtained this replica from an auction. I bought it because I was born in the year of the monkey. I am an old monkey. <laughs>

I believe everyone should fill their lives with things they like. They do not have to be very expensive things. Start when you are young, and when you look back when you are older, these things will be deeply treasured.

I feel that a person’s life is also a kind of art. Every person has their own.

This is what it means to live. 生活就是这样。

Through working on the Legends project over the course of four years, I got to know the Chinese ink masters I photographed and was deeply impacted by them. They were so humble, not at all arrogant. This has also become my life philosophy. They showed me how to live.

It is my hope that by capturing the portraits of the most significant Chinese ink masters of the 20th century, I am able to contribute and add value to the art culture in Singapore, and that this project would result in people gaining an interest in Chinese culture and tradition, and thus make sure it is passed on.