Interview with Wawi Navarroza

In her series Self-Portraits & The Tropical Gothic (2019), Wawi Navarroza allows digital-processing manipulations of the images to be visible for the first time. In the following email interview with Roger Nelson, she speaks about the work.

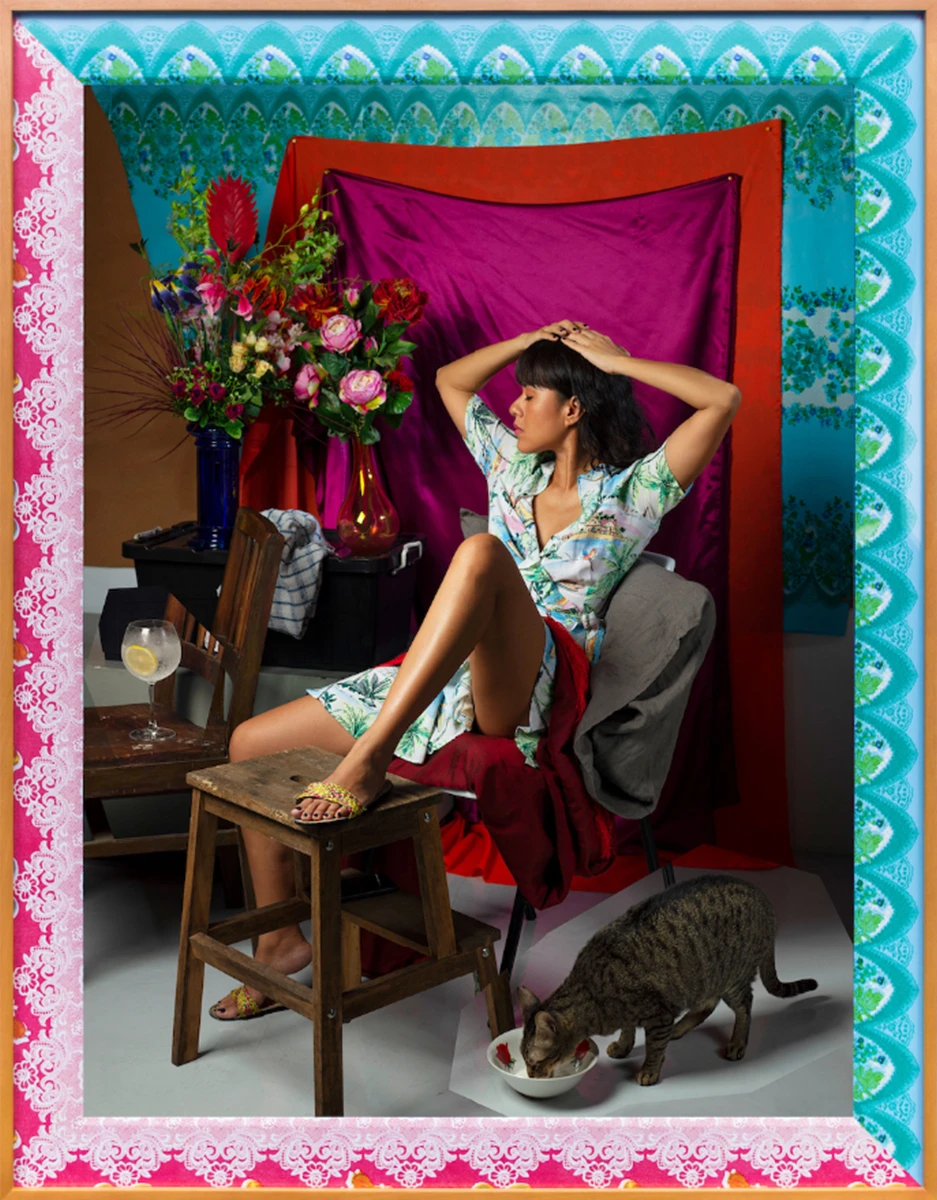

May in Manila/Hot Summer (After Balthus, Self-Portrait)

2019

Archival pigment print on paper, cold-mounted on acid-free aluminium, with artist’s fabric wrapped on double wood frame, 135.4 x 101.6 cm Michelangelo and Lourdes Samson Collection © Wawi Navarroza, 2019. Manila, Philippines.

In her series Self-Portraits & The Tropical Gothic (2019), Wawi Navarroza allows digital-processing manipulations of the images to be visible for the first time. In the following email interview with Roger Nelson, she speaks about the work.

Roger Nelson (RN): Tell us about the process of making these works. In this series, for the first time,you have introduced Photoshop as a key protagonist in the images. Why? How?

Wawi Navarroza (WN): On the contrary, Photoshop is not at the forefront of the series. It may seem so since it’s the first time it’s seen as deliberate in comparison to my other works, this “tampering with the image” (which has been held sacrosanct, and the act deemed blasphemous when it comes to photography, in reportage to be specific). But I’m not a journalist, my ideas leak into the making of the image and it’s natural to be expressive about it. Although I did cuts-and-pastes sporadically in some parts of the image, as in a glitch or a collage, the intent was to be discreet about it, hide them like riddles—and I did that with in-studio arrangement of my materials: the lighting, fabrics, colours, lines, and a very shallow (camera) depth of field which harmonises everything in a “flat” perspective. I like how it jars and disorients the eye at closer inspection. Thinking about it now, it’s not so far from the flatness of Byzantine ikon mosaics, Ottoman miniature painting, or Thai Buddhist murals. This is how I subvert the pictorial plane. Otherwise, it’s just a pretty picture.

RN: You’ve described your work as “tropical gothic,” which you explain as a “container for everything that does not make sense. This is how we are in the Philippines.” How does this sense of abundance and incoherence as being distinctly Filipino and distinctly tropical interact with your foregrounding of digital processes in this series? Is there a “tropical gothic” way of using Photoshop?

WN: “Tropical gothic” for me, in the Philippine context, in one word, is “ambiguity”: neither this nor that, but always fluid and adaptive, in many ways baffling and mysterious. And now I can actually say it makes sense. This series is a “container” but not in a way that is restrictive, but more akin to an organic experiment. My studio practice has taken after the tropical attitude towards materials: spontaneous, colourful, irreverent, creating surprises with the many combinations, hybrids, cross-information that my own culture has coded in me, but also incorporates my Western education, colonial hangover and the impacts of globalisation. Photoshop is just one of the steps in my creative process, right at the very end. The spontaneity applied in the composition of the tableaus in studio, is the same as how I use the software. All photographers now use image-processing software—it’s a given like downloading your files, whether you are an artist, commercial photographer, or anyone, really. The part where my practice deviates from common usage is how it does not aim for the final edited image to be a seamless illusion of realism. Mine takes a step aside, and the final result is an ambiguous blend of opposites—both careful and playful, smooth and clunky (think of smooth lulling waves from our seas, but then also the thud of a whole coconut falling from the tree to an asphalt ground) . I guess the “tropical gothic” way I approach image-processing is with a carefree but sincere hand, celebrating the DIY and the vernacular with cuts-and-pastes that are quick, imprecise—its a tribute to the amateur, the one who has loved first .

RN: Let’s talk about the cat in May in Manila/Hot Summer (After Balthus, Self-Portrait), and the art-historical reference you’re making in the work’s title and composition. We all know that cats rule the Internet with unceasing constancy. The reputation of the French artist Balthus, on the other hand, has shifted dramatically over time. Several exhibitions of his depictions of pubescent girls (and, often, cats) have been cancelled in recent years, over claims his work displays a paedophilic desire. What do you feel your work has to say about cats in the digital realm, and about Balthus?

WN: Cats know they’re beautiful and they’re not apologising for any of it—I know this to be absolutely true since I have two cats,Hunter and Cicciolina, who were both with me during the process of making my tableaus. They’re studio cats, which is to say, they know it’s only a matter of time before they end up in my work . Personal anecdotes aside, I do think cats carry a lot of symbolic charge and when they end up in still/static work—as painting and photographs, in galleries and in museums, particularly—they act as visual cues for triggering associations that our general culture has afforded us. What to make of the Balthus controversy? Whether to judge him on his morality or his work as an artist deserves a long debate. My curiosity in making a tableau with reference to Thérèse Dreaming comes from the experience of being the Other, observed—Woman, Exotic, Far Away. In May in Manila/Hot Summer the Balthus-charge is impotent because, this time, the subject is aware and awake: the Other is enjoying herself on a hot summer day—and she photographed Her herself. In my art practice, I occasionally refer to Western art history, turning the mirror back on itself in many layers. It raises questions on the hybridised Filipino identity, the female Asian body, the female body in relation to youth, sensuousness, exoticism, pleasure, and tropicality.

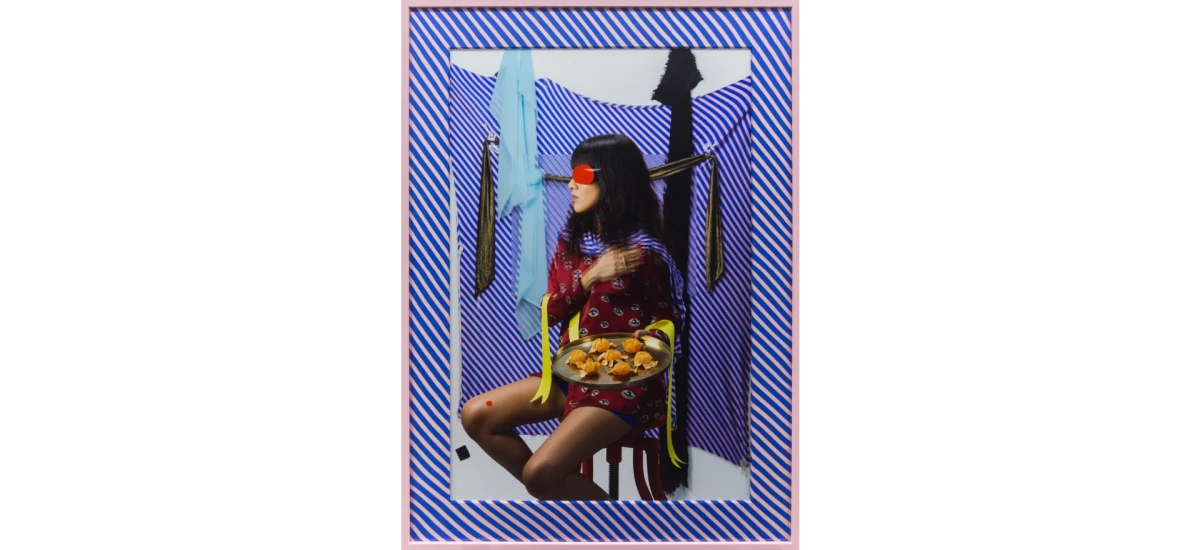

RN: The swathes of striped fabric–both real and photographed–dominate A Lesson on Looking. But what role do the smaller details play in this work? Red stickers above your knee and over your eyes, mandarin oranges, yellow ribbons, and of course the eyes printed on your shirt–these intriguing elements appear almost like clues in a puzzle…

WN: Yes, I do like to play with codes and mini trompe-l’oeils. Ever since I was a teenager, I have seen the world in symbols: objects as talismanic, the correspondence of things always present for those who are keen to know more (symbols can lie muted too, and this quiet/stillness is also interesting) It’s all in the smaller details (thanks for noticing them!). For this image, there’s a lot of referencing to the eyes and see-ing. When you cover the eyes you are forced to look somewhere else—inside. And then there’re the thousands of eyes she’s wearing: it’s all eyes on the image, and every new viewer adds another eye through the transparent glass of the framed image. There’s a Catholic image—stampita—of Santa Lucia where she has a palm leaf on one hand and a pair of eyes on a plate on the other. I took to that iconography and replaced the eyes with seven mandarins. Instead of eyes, we can also see with mandarins, which represent to the Chinese future, abundance and fertility. The heart is pumping in her chest and her hands vibrate with this thumping of life and it repeats again and again, just as her fingers are digitally doubled in the image.

RN: Your professional-grade photographic studio lights are visible in a reflection on the vase in May in Manila/Hot Summer (After Balthus, Self-Portrait), while bits of sticky tape holding together the backdrop can be seen in A Lesson on Looking. Your recent works balance a high level of slick photographic skill with deliberately lo-fi and amateurish-looking elements. How do you decide what to reveal, and what to conceal?

WN: This often gets missed in the reading. When I’m making the works, as the thinker of the ideas, the production and set arranger, lights and camera technician and as the figurative subject, I go about it very spontaneously; my sketches are very rough and the composition is assembled on the fly with the materials strewn around the studio. It’s a very physical process: I’m in a trance and the studio is a spaceship . Only after I see the final image, can I can see my hand in it—vacillating between opposites, there is always a “yes but no.” My tableaus seem to always have a dualistic ambiguity : the careful planning, placing and arrangement of mise-en-scène, technical tricks on photographic light, high quality camera rendering, AND/BUT there’s the bricolage aspect of it, more lo-fi, where hanging of fabric is improvised, tapes and tools are exposed, impatient, imprecise; sometimes the framing on the viewfinder has “leaks” revealing the studio/stage (where it was shot) but very, very little—this in itself a part of my intent, an optical manoeuvre, a sliver/peek behind the curtain through the many layers of fabrics thoughtfully placed. I retract and reveal in order to remind the viewer that photography is malleable and is very much a contemporary art medium to construct the image, to propose interstices, to break and tear, and to stitch again and again what once and still is in the process of being explored, understood, decolonised and reclaimed.

Wawi Navarroza

20 May 2022

Istanbul, Türkiye

An abridged version of this interview was published in the exhibition catalogue Living Pictures: Photography in Southeast Asia. Find out more about the exhibition here.

The Perspectives Editorial Team would also like to wish our readers Happy International Women's Day! If you would like to find out more about women making art during the 19th century in Southeast Asia, check out this article on our magazine that surveys the research that has been done in this field.