At Work with the Dance Constructions

Simone Forti’s radical Dance Constructions redefined the relationship between bodies and objects when first presented in New York in 1961. Based on everyday actions, chance, and improvisation, and the use of simple materials such as plywood and rope, the pieces break with the idea that dance can only be performed by formally trained bodies. Sarah Swenson has been the principal teacher of Dance Constructions since 2012. In this article, she reflects on the intricacies of teaching, learning and performing works predicated on human effort and interaction.

Simone Forti’s radical Dance Constructions redefined the relationship between bodies and objects when first presented in New York in 1961. The dancer and choreographer's work is characterised by her exploration of natural, non-formalist movements. Based on everyday actions, chance, and improvisation, and the use of simple materials such as plywood and rope, the pieces break with the idea that dance can only be performed by formally trained bodies.

In 2019, the Gallery presented three of these historic works—Platforms (1960); Slant Board (1960); and a new version of See Saw (1961) interpreted by Singaporean performance artist Rizman Putra—in Singapore1 for the first time. The performances were part of Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. (16 November 2018–14 April 2019), an exhibition that examined the emergence, development, and legacies of Minimalism from the 1960s to the present day.

"At Work with the Dance Constructions"

Sarah Swenson

January 2020

Author’s note: This piece was finished shortly before we were consumed by the Covid-19 pandemic. Because the Dance Constructions are the epitome of physical relationships and close contact, reflecting upon them and yearning for them has become all the more poignant.

~

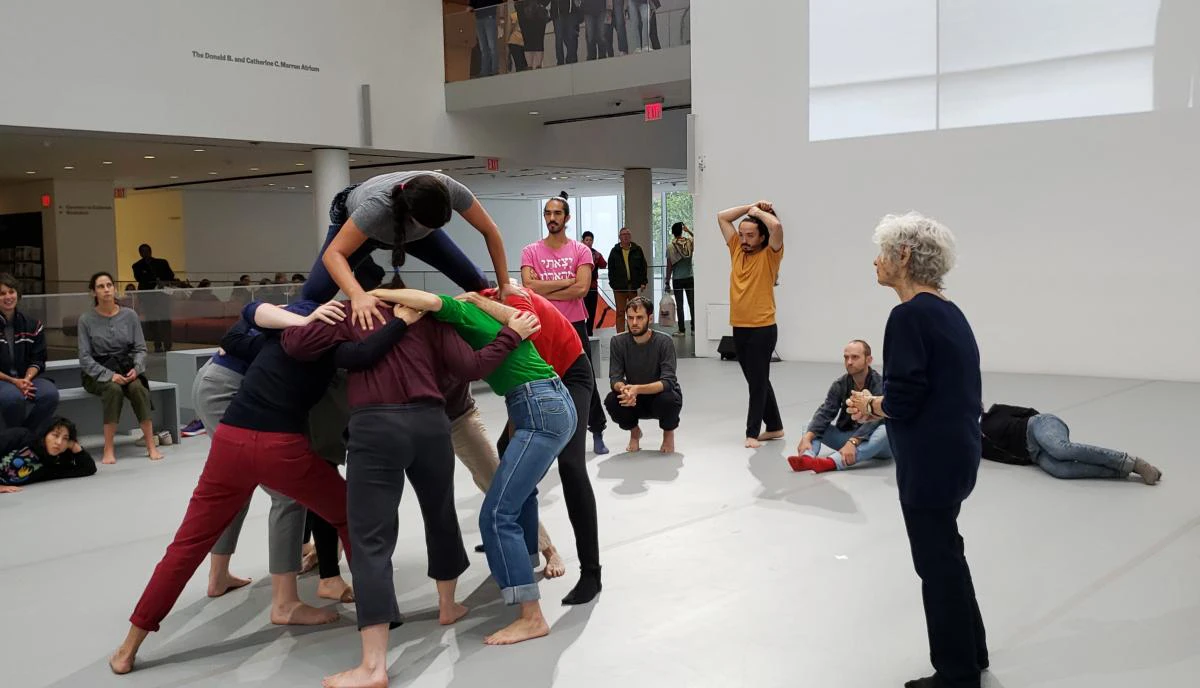

Huddle: in which a group of people form a mound and take turns climbing over the top

Roller Boxes: in which one person sits in a cart with wheels and is pulled by two others with ropes

See Saw: in which one or more people create a new piece using a giant wooden see saw

Slant Board: in which three people traverse a 90 degree slanted board using knotted ropes

Hangers: in which three people hang suspended in loops of rope, while four others pass between them

From Instructions: in which two people strive to achieve conflicting physical goals, spawning a struggle

Platforms: in which two people lie whistling and listening to each other, each under a long box

Accompaniment for La Monte's 2 sounds and La Monte's 2 sounds: in which a person hangs suspended in a loop of rope listening to a composition by La Monte Young

Censor: in which two people face each other, one singing, and the other shaking a pot of nails

__

Since 2012, I’ve been at work as the principal teacher of Simone Forti's seminal 1960's oeuvre, Dance Constructions—and since late 2015, when they were acquired by MoMA’s Department of Media & Performance Art—also their International Project Coordinator. Originally conceived as five pieces presented in May of 1961, the Dance Constructions today are being performed in museum and gallery exhibitions of unprecedented scope and duration. This phenomenon has necessitated the formation of a complex loan planning process between MoMA and the borrowing institution involving curators, directors, archivists, managers, designers, builders, performers, and myself, commencing at least a year in advance. Recruitment of performers, (often called movers), teacher selection, and a carefully arranged and tightly packed teaching period culminate in an opening—the launch of a performance installation lasting anywhere from one day to six months—sometimes utilizing as many as 60 people.

Now a collection of nine pieces, the Dance Constructions all possess certain characteristics in common, yet each has a distinct quality, intention, and origin: a dream, a memory, a yearning. Huddle, Simone’s signature work, was a response to an assignment given by Robert Dunn at his now-famous 1960s dance composition workshop based largely on the chance operations of composer John Cage: "Create a 3 minute piece but don't spend more than 3 minutes working on it." The resulting Huddle satisfied her need to be physical, just see the human body, and importantly—not know what would happen next; this was one of John Cage's core concerns.* Both an activity and sculpture formed only by people, Huddle is the one Dance Construction that doesn't utilize some kind of built structure or object—the rest are all constructed and installed anew for every exhibit, specifically to be used by people.

All have some element of sound—often, but not always subtle; sometimes produced by the effort of a given action, sometimes an intentional conceptual element. And each one of the Dance Constructions requires a different physical skill set, while they all demand a certain demeanor, body awareness and energy—all anchored in the firm intention to stay present. Such simplicity lies in stark contrast to 21st century life, yet the now 60-year-old Dance Constructions have become classics, with much to teach us and draw upon.

The team of performers in a given city are usually drawn from visual art and dance schools, local performing artists of varying backgrounds, occasionally circus performers, actors, and musicians—often a heterogeneous group with varying levels of experience in movement performance. But I have found that the range of possible activities included in the Dance Constructions—from the ability to whistle while lying down (Platforms); to having the strength to hold one’s own body weight for ten minutes while climbing up, down, and across (Slant Board); to submitting to a gleeful and terrifying ride (Roller Boxes); to possessing the concentration necessary to just listen for thirteen minutes and not space out (Accompaniment for La Monte’s 2 sounds and La Monte’s 2 sounds)—has always meant that there is something for everyone. Both the beauty and the challenge of each Dance Construction lies in its simplicity—the ability to embody an effective performance of any of them lays bare the brilliance of Simone’s concept, and in my imagination, will make the viewer want to do them, too. And when a performance is over, the structures rest in space, riveting in their silent potential.

The number of pieces chosen by a curator can be as few as one, or as many as of all of them; sometimes other works of Simone’s are requested, such as drawings, videos, holograms, or other performance and conceptual pieces. Transmission of the work is intense. As each Dance Construction has just a couple of specific tasks, the biggest obstacle to success for a performer can be doing more than is asked. Suppressing the desire to elaborate is essential, thus one must engage self-discipline. Simone credits The Gutai Group of Japan with her realization that a single action would be enough to constitute a creation, such as in the famous Passage (1956), in which Saburo Murakami forces his body through several frames of stretched paper, lasting only a few moments.

The nature of project-based work means that one is continually working with strangers. For the Dance Constructions, this a necessary and integral part of the works' realization, because each installation is uniquely shaped by the individuals chosen to perform in it, along with the physical environment, country, city, and cultural setting in which it is presented. I am always fascinated by the grand variety of personalities I encounter, and consider it one of the blessings of my labor, albeit bittersweet, because I am always saying goodbye. Once in awhile, some connections endure.

Often there is a very short time to determine who will perform what, and to select an order and mode of presentation, sometimes involving multiple exhibit areas and building levels. One worries both about disappointing or under-estimating a performer—but decisions have to be made quickly so that dress-rehearsals can commence and adjustments made. A carefully planned rehearsal schedule can be interrupted by non-functioning wheels (Roller Boxes); or ropes not quite hung to specifications (Hangers); stray nuts and bolts emerging from an aluminum pan (Censor); questions about precisely where to affix blocks to the wall (From Instructions); or last-minute visits from the press—the entirety of the process can feel acrobatic. At the end, it is not a quite a dictatorship, and everything is finalized in collaboration with the curator, whose vision for the exhibit must also be considered. And nowadays, in keeping with Simone’s endless capacity for brilliant ideas, the classic See Saw has been retired as a taught Dance Construction, and is now generously offered as a gift to be reimagined and recreated anew by invited artists around the globe.

An aspect of the Dance Constructions seldom discussed is the experience of the movers, usually expressed in terms of how the work has transformed their sense of themselves, their place in the universe, expanded their connection to others, or simply, provided pleasure:

“Roller Boxes - this Construction had some sort of caffeine effect on me. Secretly I was never very eager to do it. It seemed like an extremely demanding physical task that I wasn’t looking forward to. Thinking that I was too tired or lazy that day to run and pull not only my weight, but the weight of another person, meanwhile being conscious of the limitation of the space, of other boxes, of other people, and lastly of my passenger who trusted me to give them a ride. Yet oddly enough this idea of me being responsible for this passenger’s safety and enjoyment fueled me. I started to care so much for that passenger, and I felt that my pulling partner would always feel the same way. I took great pleasure in ensuring that the sitter would have some kind of experience. Ten minutes would fly by as we ran and experimented with the physics of momentum and shape, of collaboration. In the end this became one of my favourite Constructions of all. It had the most diverse outcomes, the most unplanned mishaps that contributed to its effectiveness.”

~Daniel Conant, Canada

“Doing what you do is good enough…that was what I liked. But it also seemed the biggest paradox or contradiction in me. Because when I do what I do, I normally act intuitively and a bit over-enthusiastic. Doing “normal” was difficult, and the challenge was to fit into the performance, to bring it into a balance. Some kind of duality, I felt.”

~Chantal Minnaard, Netherlands

“i also appreciate the poetry with which individual strangers can come together for such a short time to dedicate ourselves to each other and to art action. there is a kind of faith when we allow a partner to hold us up in huddle or to hear our small whistling cry (manipulation of air) in platforms. something about moving and interacting with the body together creates a bond even stronger than through the conventional conversation. for a few hours in a day i experienced embodying my aliveness. and i look forward to expanding that into the other aspects of my life.”

~art naming, Singapore

A Minimal Understanding

A rope in the hand

And the subtle shift

From left to right

Balance weighed

Feet, legs, torso,

Head searching

To release thought

Into pure movement

Becomes stilled

Silence and then

A box resonating

Tone and space

Into expanding

Now observing

Sound and light

Into the infinite all

Filled with bodies

Shoulders, arms, legs

The soft pressure

Of a moment of together

Of clarity of alone

Climbing up over

Heads bent in feeling

Into individual we.

~Dawn Nilo, Switzerland

“I was surprised, perhaps naively so, to discover that gaining this physical knowledge of the performances drastically differed from observing them, a realization that has informed not only my own comprehension of the Dance Constructions as artworks, but has greatly influenced my perspective on the implications of stewarding these within an institutional context. Ultimately, by assuming the roles of both archivist and performer, the unique challenges of how an institution might take on the responsibilities of actively facilitating knowledge transfer and managing networks of knowledge-keepers have become both a professional and personal investment.”2

~Athena Holbrook, former Collections Specialist, MoMA

“I started with 20 instructions and reduced it to 5 in the end. Then I began to realize Dance Constructions is really about a work-in-progress whereby the process is the teacher. Hence, I understood it as constant construction, as it is the same never the same thing as you do it in repetitions. At that very moment, in connection to minimalism, we have to learn how to deal with the notion of stripping bare. Simone Forti’s work has made me realize the power of simplicity is essential in the process of art making.”

~Rizman Putra, invited See Saw artist, Singapore

“When I do the Dance Constructions I feel very present. It’s like a moment to gear up the awareness, both independently and as a group. The tasks stay the same, but there are always new things to experience—either through the dynamic of the people you are moving with, the environment, or through your own focus and state of the day. The simple nature of the Dance Constructions and the clear tasks help me to keep a clear focus, and the set time makes me able to dive into the task even more: ’This is what I’m doing for ten minutes, nothing else.”

~Jasmine Attie, Sweden

This feeling expressed by Jasmine, that the time limit allowed her to go deeper into the performance, has informed my teaching. The truth of this observation resonates and is a helpful piece of information I can convey to future movers - an excellent mental attitude for achieving the requisite state of absolute presence. When performing Accompaniment for La Monte’s “2 sounds” and La Monte’s “2 sounds” myself, for instance, perhaps one of the least physically active pieces of the collection, I find that adhering to the intention of the piece implies a certain relinquishment of will - a submission to the desire of another, letting go into the single task - and yet I lose nothing, descending more deeply rather into that intangible locus of creativity, while simply listening to its near-deafening but fantastic score by La Monte Young.

Sometimes Simone and I teach together. This is a precious experience, and always results in some new revelation, and occasional acts of spontaneity. In 2017, at the Musee d’arte Carre in Nimes, France, while explaining to rapt student performers her habit of observing animals, she suddenly said: “This is how a bear turns around,” tossing her upper body in an arc and swiveling—and then launching into an impromptu 10-minute performance. These are moments to cherish, not only for myself, but for the most often rather young generation of performers who have been selected.

And when Simone is not present, which is most of the time, I feel her absence. At times I give way to insecurity because—I am not Simone—I can’t possibly convey the essence of Simone, which is the very DNA of the Dance Constructions. Overwhelmed by an impossible responsibility—while it is one that I have welcomed—I think: there’s going to be some resolution loss, right? And then…right. I’m not an exact copy, and in keeping with spirit of the work, which I feel is driven by the pursuit of renewal, I have to trust, as she has trusted me, that an exact copy is not required. While intention won’t change, there will be slight shifts in perception, observation, and approach. Each future teacher will have a little bit of freedom to imbue the work with her own sense of the moment, in concert with the constellation of individuals with whom she is working, just as Simone herself does. On my own, I feel I am conveying some kind of absolute truth—because the Dance Constructions are so very much about being human, and having a human body: the one denominator shared by every single person on earth. In the succinct words of Vitor Daneau, a performer in the Sao Paulo Bienale of 2012, “My friends, we are hanging for our very lives.”

Today, like many other collaborators, company members, and students of early and mid-20th century innovators, second generation Dance Constructions teachers (Claire Filmon, Carmela Hermann, K.J.Holmes, Batyah Schecter, and myself) are finding ourselves face to face with our elders’ mortality: Simone Forti - 88, Rudy Perez - 93, Yvonne Rainer - 87, Steve Paxton - 83, and many others.* Premature grief for this dreaded eventuality invades my heart too often - but, turning that thought away, I employ the primary lesson of the Dance Constructions: stay present.

In dialogue with Simone, the learning never stops, there is always something new to hear, observe, contemplate, discuss. But not only are we learning how to even more effectively transmit the concepts, mechanics, and origins of the Dance Constructions, we don’t want those precious moments, in the case of each of us, born of long and close relationships with Simone, to end. It isn’t just work—it’s love.

~

Notes

- Singapore performers: art naming 奇能, Nirali Desai, Rachel Lim, Neo Jialing, Sonia Kwek, Yulin Ng, Rachel Nip, Isabel Phua, Regine Phua, Wong Kwang Lin, Shangbin Xie

- Athena Christa Holbrook (2018), “Second-Generation Huddle: A Communal Approach to Collecting and Conserving Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions,” Contributions to the Preservation of Art and Cultural Property 1: 118–123.

- * Factual updates were made in November 2022.