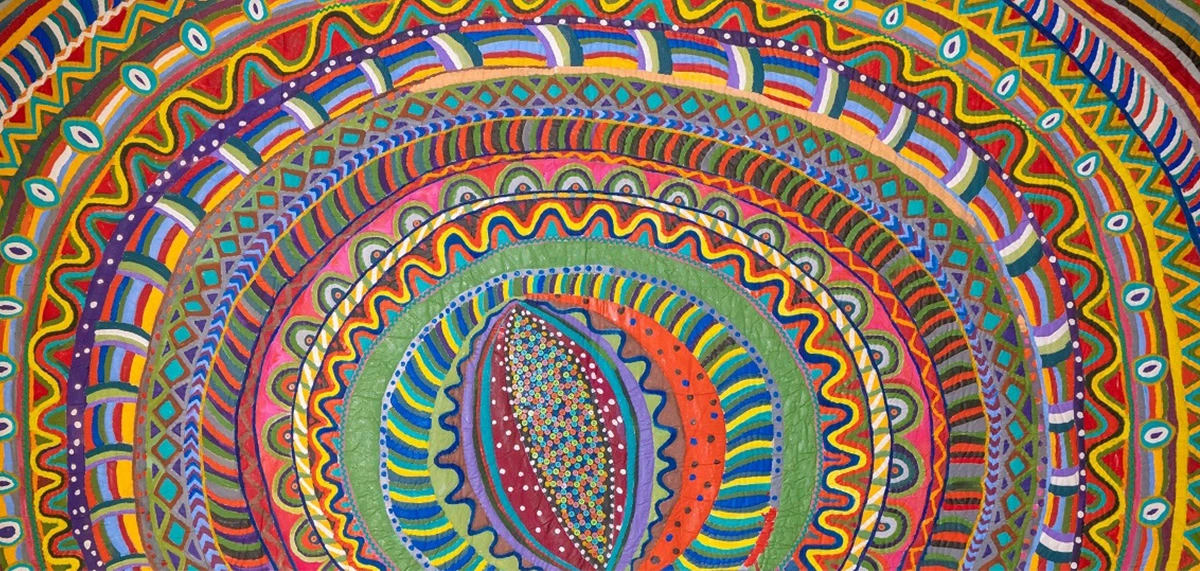

A look into Evil Eye by Pacita Abad

According to traditional beliefs, depictions of the evil eye could ward away a malevolent gaze. Curator Cheng Jia Yun explains how Philippine artist Pacita Abad’s artwork is more than meets the eye.

Evil Eye, 1983

Acrylic, plastic buttons and ribbons on stitched and padded canvas

133.0 x 255.0 cm

Gift of Jack and Kristiyani Garrity

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

On display in the UOB Southeast Asia Gallery alongside works by other women artists active in the region, Evil Eye is based on the handwoven design of bread basket covers that Pacita Abad bought in the open air market of Omdurman, Sudan. During her time in the country in 1979, she became intrigued by these basket covers and decided to make a trapunto painting inspired by their design. This depiction of the evil eye is rooted in the traditional belief that it can repel a malevolent gaze.

Pacita began creating trapunto paintings such as this in 1981, marking her departure from conventional paintings typically concerned with social realist themes. Trapunto refers to the stuffing technique that was used to create high relief in 14th century Sicilian tapestries. She began Evil Eye in her studio in 1982 shortly after returning to Boston from Africa, and completed the sewing and embellishment of the work in Manila in 1983.

Evil Eye centres around a nucleus densely packed with carefully coordinated multicoloured buttons. The dense and interlocking patterns here can be seen as a reflection of Pacita’s deep interest in the ethnic cultures she encountered, both growing up and throughout her travels to Bangladesh, Sudan, Papua New Guinea, the Dominican Republic and Indonesia. On the underside of Evil Eye, numerous running stitches are visible, revealing the labour of stitching and stuffing which undergirds the work’s robust texture. Sewing the topmost fabric onto a muslin base using a simple running stitch, Pacita created pockets that were carefully stuffed to create the high relief that characterises trapunto.

Evil Eye can be read as an early assertion of the vibrant visual language that Pacita’s works have become known for. Compared with other works from the same period, Evil Eye stands out for its radial and non-referential composition that takes on an abstract quality. While it was originally intended to be hung vertically, Pacita was open to the painting being displayed horizontally as well, even giving it a less ominous title, Watermelon.