Between Declarations and Dreams of Southeast Asia since the 19th Century: Galleries

Authority and Anxiety

The story of modern art in Southeast Asia began with the drastic cultural and political changes of the 19th century.

By the second half of the 19th century, most of Southeast Asia was under the control of European colonial powers. In most cases, this form of control was distinct from the trading and religious interactions with Europe in previous centuries and had a more direct impact on the structures of local political power and cultural life.

Even Siam (now Thailand), which remained independent, was not immune to the effects of colonisation in the region. Greater cultural contact with the West influenced the kind of art produced in Southeast Asia at this time. Local elites used art to defend their status, which could be threatened by a changing social order.

While many artists and artisans continued to produce the images and objects that they had in the past, others began to make use of new tools, styles, and genres of art from the West, which signalled a conceptual break with tradition. This sense of a break, or change, can be understood as the beginnings of modernity in art.

Featured artworks in this gallery

Imagining Country and Self

In the early 20th century, artists in Southeast Asia became more aware of their identity as modern artists and began to express a stronger sense of place in their works.

By the 1920s, the consolidation of colonial rule by the Dutch, British, French, and Americans was complete for most parts of Southeast Asia. Consequently, the region experienced ever more rapid change and continuing social inequalities. This led to increasing calls for reform and independence, which were echoed by anti-imperialist movements in the West.

Fuelled by a growing sense of nationalism, local artists expressed a deeper connection to their home in their work. From the popularity of picturesque landscape paintings to a synthesis of local themes and materials with a new visual language, artists showed a heightened sensitivity to place.

At the same time, the establishment of new art academies and exhibition systems gave rise to the identity of the “professional artist”. As a result, artists actively strove to express their newly found “self” through innovative forms.

Featured artworks in this gallery

Manifesting the Nation

Driven by notions of the nation, internationalism, and progress, artists from Southeast Asia continued to examine the role of art during an increasingly complex environment.

Southeast Asia experienced World War II, the struggle for independence, and the rise of post-war nationalism in close succession. As fledgling nation-states came into being in an unstable political atmosphere, alliances like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) became a platform for regional cooperation. The subsequent Cold War divided the countries and this, in turn, influenced artistic directions, both directly and indirectly.

Artists responded to nation-building in various ways. During and after World War II, artists documented political events and issues and engaged with social realism to awaken feelings of nationalism and spur people into action.

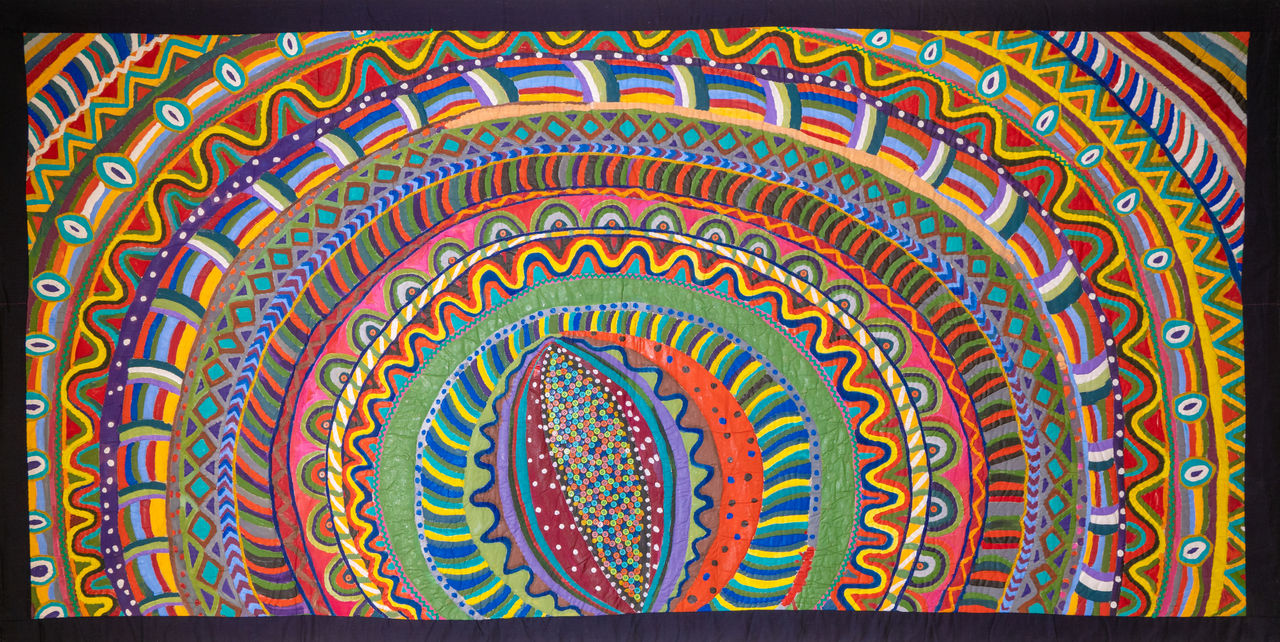

At the same time, artists were also eager to participate in international trends and exhibitions where abstract art held sway. These artists explored formal concerns such as colour, shapes, and composition. Simultaneously, they also turned to their roots for inspiration by reinvestigating local traditions, materials, and subject matter.

As the Cold War reached its height, new social-political phenomena like the rise of student movements and popular revolts against authoritarian rule became widespread. A new generation politicised the function of art and the responsibility of the artist.

Featured artworks in this gallery

Re:defining Art

In the decades after 1970, artists challenged the dominance of painting and sculpture.

Artists asked critical questions about art and the circumstances in which it was created. Using a wider range of approaches and materials, they experimented with other genres such as installation, video, photography, and performance.

This new impulse in art was prompted by the consequences of militaristic exploits, human and environmental costs of the Vietnam War, and other authoritarian dictatorships in the region.

The end of the Cold War in 1989 led to shifts in global dynamics. This was also reflected in changing ideas about power, such as critical perspectives in postcolonialism and feminism. Concern for the disappearance of local heritage and disaffection with Western consumer capitalism led artists to incorporate traditional iconography, knowledge, and craft into their art.

Artists also questioned their own identities, whether national, ethnic, spiritual, gendered, or sexual. They made art that re-examined suppressed historical narratives and traumatic memories, thereby providing alternative readings of the past.

As artists from Southeast Asia became part of the global art world from the 1990s, the impact of Euro-American art schools, international biennales, and art fairs grew more important. Artists had to work with institutional and market structures, and the inner workings of the internationalised art industry.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.tif/_jcr_content/renditions/1080p.jpg?ch_ck=1723877803000)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.tif/_jcr_content/renditions/1080p.jpg?ch_ck=1722393274000)

%20copy.jpg)