Women Making Art in the Long 19th Century: Some Glimpses

There are exciting and remarkably varied examples of art made by women in 19th century Southeast Asia, but research has largely overlooked these artists in favour of their male counterparts. Curator Roger Nelson spotlights some of the paintings, photographs, textiles and other media created by female artists of the time, offering an introduction into this significant area of art history.

Detail of Untitled (Caboe, Servant Maid)

c. 1900

Albumen print on paper

16.5 x 12.9 cm

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Did women make art during the 19th century in Southeast Asia? Or were they only depicted in artworks made by men during this period? The 19th century is generally recognised as the beginning of modern art in this region; it is also a time when social relations, including those between men and women, were transforming along with the colonial encounter and other upheavals. Much less is known about artists from the period who were women, and much more research is needed in this field. Many accounts of 19th century art in Southeast Asia tend to overlook the question of gender and sexual difference, often as a result of their focus on male artists and their male patrons. Similarly, many studies focused on “women artists” in the region consider only more recent decades in the 20th and 21st centuries, often because these artists make explicitly feminist work. Yet there are more stories to be told.

There are exciting and remarkably varied examples of art made by women in the 19th century. Studying these can expand and enrich our understanding of how the new visual languages of modernity were articulated in Southeast Asian contexts. This article offers a brief introduction to a few key instances. It begins with a survey of some surviving oil paintings made by female artists, and then turns to artworks in other media. This article is written in the hope that these glimpses might lay a basis for further studies. A list of scholarly works cited (many of them available online), and suggestions for further reading, are included at the end of the article, which is intended chiefly as a survey of prior research in the field.

Women Making Paintings

This extraordinary painting in the Prado’s collection is titled Una Mestiza. Made in 1887, the painting has been in the Spanish national collection for over a century. The artist, Granada Cabezudo, was born in 1865 in the Philippines, and died there around 1900. Una Mestiza was exhibited in 1887 in Madrid, and is likely the only artwork by a woman from Southeast Asia to have been exhibited in Europe during the 19th century. Cabezudo and her female peers in the Philippines have been researched by scholar Eloisa Hernandez.

The painting depicts a young woman dressed extravagantly in lavishly layered gowns of fine lace; she carries a bible in her left hand, which suggests that she is literate. With her right hand, she gathers the folds of frosted pink fabric from her skirts, in the process revealing a black shoe embellished with delicate white beads or lace. Visible in the background of the composition are attap huts and the lush tropical foliage of banana palms, sugar palms and tall trees. The scene likely depicts the titular mestiza woman (a term referring to mixed ancestry) walking from her rural village to church, dressed in her Sunday best.

While the picture is appealing and offers some insight into the social circumstances of its day, it is nevertheless quite clumsily painted and in lamentably poor condition; what makes this artwork truly extraordinary is its rarity as an oil painting by an artist who was also a woman. Cabezudo’s is one of only a small number of known extant paintings from the 19th century made by female artists, and done in oil on canvas, the privileged medium of modern art at the time.

Cabezudo was fortunate that her work was collected by a museum; many other works by artists who were women, such as Pelagia Mendoza (b. 1867, Philippines; d. 1939, Philippines) and Carmen Zaragoza (b. 1876, Philippines; d. 1943, Philippines) are presumed lost or destroyed. Their importance has rarely been recognised by scholars and curators, despite Mendoza being the first woman permitted to study in Manila’s School of Drawing and Painting (Escuela de Dibujo y Pintura), which from its establishment in 1820 until 1889 had accepted only male students. Both Mendoza and Zaragoza were also awarded medals for their artwork in 1892, which were reproduced in prominent Philippine periodicals of the time.

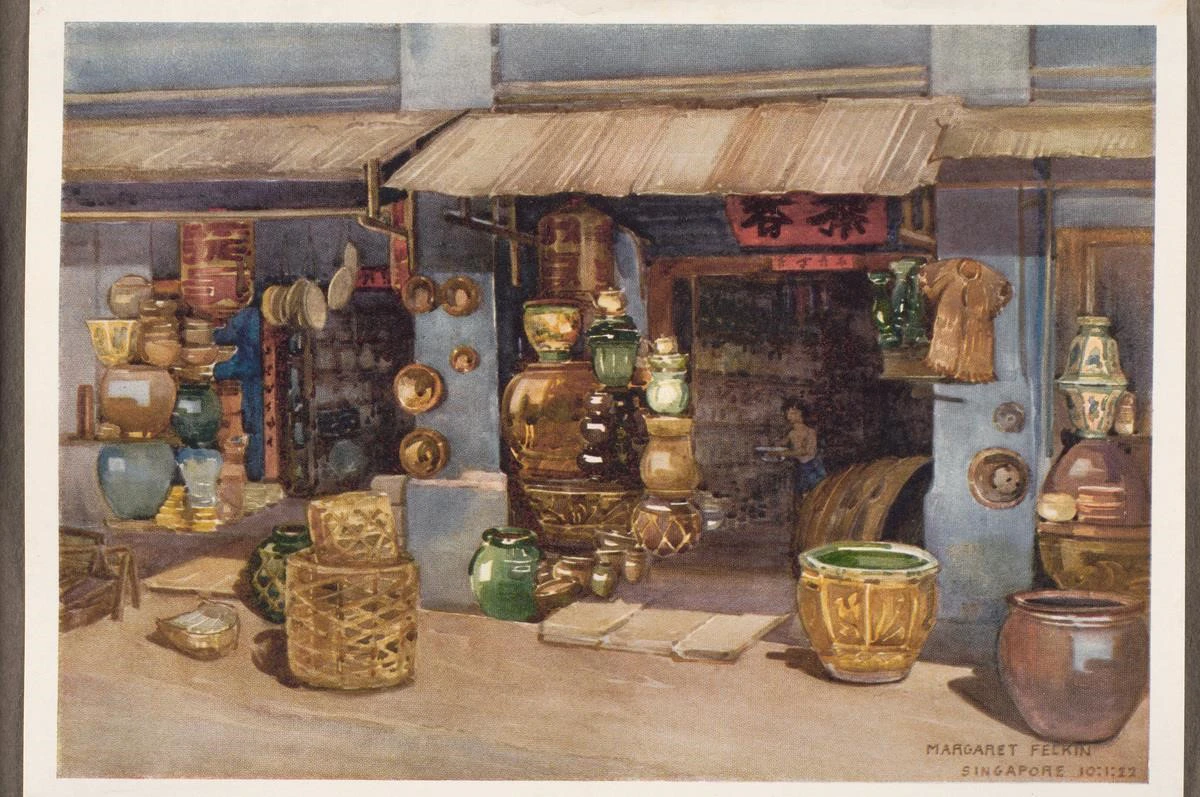

It is impossible to know how many other drawings and paintings made by women might have been lost, and it is very likely that more will be rediscovered in the future. Women were active as amateur artists in the Singapore Art Club from at least the 1880s; while most of their works have not been found, their lives and art have been studied by Yvonne Low. One extant sketch by artist Margaret Felkin (British, active c. 1910s to 1930s) gives some indication of the widespread interest in depicting quotidian scenes of street life in Singapore. While Low does not discuss this sketch, she records that Felkin served as honorary secretary and treasurer of the Singapore Art Club in 1912, as part of an all-female management committee. In hoping that more artworks by amateur artists from the colonial period might come to light, we can be encouraged by the fact that in Australia, a large number of important artworks by colonial officers’ wives and other women artists were only located and examined by scholars and curators after the 1980s, despite the existence of museums and other institutions in the country collecting and studying the work of their male counterparts for well over a century before then.

Other surviving paintings made by women in the 19th century include a competent botanical illustration by Emma Vidal (b. circa 1855, Philippines) published in 1877, and several fine oil paintings on canvas (such as still life works) by Paz Paterno (b. 1867, Philippines; d. 1914, Philippines), as well as by her sister Adelaida Paterno (b. 1880, Philippines; d. 1962, Philippines). In addition to painting in popular genres such as landscape and still life using the conventional medium of oil on canvas, Adelaida Paterno also made several captivating artworks by embroidering with human hair. Although this technique is highly unusual, it was not at all uncommon for women to make art in diverse media during this period.

Women Making Photographs

During the 19th century, most artworks by women were not oil paintings, but in various other media. This would likely have been at least in part due to women’s exclusion from opportunities to be trained in the techniques of oil painting. Some surviving artworks in other media, as well as some tantalising traces of them in historical records, can be found from several locations outside the Philippines.

In Bangkok, a number of women who lived with King Chulalongkorn (Rama V, r. 1853–1910) as his official royal concubines also practiced the art of photography during the late 19th and very early 20th centuries; their work has been examined by scholar Leslie Woodhouse. The images captured by these pioneering female photographers convey with electrifying intimacy the ways in which photography had been integrated into women’s daily lives within the cloistered royal confines, as in the image of a camera set up on a tripod alongside a group of concubines picking fruit from a tree. Many of their photographs depict women in the palace compound posing proudly with their cameras, like the one above of a woman named Erb Bunnag in the act of photographing her father. Although the individual author of each specific picture is unknown, the closeness of the five sisters from the Bunnag family, known as the “Kok Oh” or “Oh Clique,” was well-known in the palace and is clearly intimated in several of these images. Perhaps this suggests a somewhat collaborative approach to the practice of photography.

A distinctly modern medium, photography was famously taken up by King Chulalongkorn himself, as well as other elite males in Thailand. Yet images by these male photographers often tend to be more formal and stiffly posed. This is seen in photographs by Francis Chit (b. 1830, Thailand; d. 1891, Thailand), who is considered the earliest Thai photographer. In contrast, the mood of pictures taken by the Bunnag sisters and other women of the royal court are quite different. Many depict these women and their easeful confidence with the camera. It is in these informal, even candid images that we get an especially vivid sense of the thrilling novelty of photographic technology, as a distinct marker of modernity.

The female photographers in King Chulalongkorn’s royal court were not the only women to take up the camera during the period, and demonstrate considerable artistic skill. The earliest female professional photographer in the region was probably Thilly Weissenborn (b. 1883, Indonesia; d. 1964, Netherlands), who began working in a successful studio business in Surabaya in 1913 before heading her own studio from 1920. She made portraits, captured temples, and also produced stunning landscape photographs. As well as being beautifully evocative images, these also align closely with the aesthetic conventions that were popular in paintings at the time, often referred to as “Mooi Indie.”

But before Weissenborn, it is very likely that there must have been amateur photographers in Southeast Asia who were women. The earliest male photographers from Europe began capturing images in the region as early as the 1840s, very soon after the invention of the medium. Photography soon became a popular pastime for amateurs, as well as a professionalised practice.

In an 1899 publication titled An English Girl’s First Impressions of Burmah, author Beth Ellis (b. 1874, United Kingdom; d. 1913, United Kingdom) vividly describes her thwarted intention to take photographs during her travels in Myanmar. “I ventured once or twice to the bazaar with my camera,” she recalls, but the Burmese people she encountered “did not understand it, and regarded [her] with suspicion.” Nevertheless, Ellis records that she “took photographs with great vigour and confidence during [her] travels.” In a “most disappointing” turn of events, “not a single one of them developed,” due to a mysterious technical problem with the camera, film, or perhaps both. “It is a singularly distressing employment to sit long hours in a stuffy dark room, developing photographs which steadily refuse to develop,” Ellis lamented. Before travelling to Myanmar, Ellis had studied at Oxford University, although women were not yet entitled to earn degrees there.

While Ellis was a trailblazer, she was certainly not the only European woman to spend time in Southeast Asia. Just three years before Ellis’s book, Gwendolen Trench Gascoigne’s Among Pagodas and Fair Ladies: An Account of a Tour Through Burma was published in 1896. In it, the author devotes an entire chapter to Burmese women, asserting that “[t]he Burmese are all ‘new women.’” She further notes that in Yangon “among the richer classes, the women are often very well educated, and some are quite learned in Burmese literature.” Gascoigne also recounts being presented by a Burmese woman with a photo-portrait of herself, as a gift. Her publication is illustrated with photographs, but she is not recorded as having taken any herself.

Did other female colonial travellers, or perhaps colonial wives or European women in Southeast Asia for other reasons, also make photographs during their travels in the 19th century? Did they perhaps find better luck than Ellis did when developing these images? Given the popularity of the medium, and its documented adoption by women in the region at the time, it is very likely that they did. But regrettably, their works seem not to have been rediscovered or studied to date.

Women Making Textiles

As well as embracing new media like oil painting and photography during the 19th century, women in Southeast Asia also worked in textiles and with diverse other materials usually thought of as “craft.” Nowadays, we tend to regard craft as quite different from art, but that distinction was not always so clear. While textile-making was not new, these practices were also transforming in various ways, including with new technologies and materials becoming available as a result of intensified trade and contact, as well as emerging markets.

Textiles and other materials now thought of as craft are often collaboratively made, or else not ascribed to a single author or maker; they are typically anonymous. As a result, the names and individual achievements of women practicing in these media have largely been lost over time. What remains, however, are tantalising traces in various historical records, which often point to the surprising intersections between these women and other artistic, cultural, and even political phenomena.

A number of photographs by Kassian Cephas (b. 1845, Indonesia; d. 1912, Indonesia), depict women engaged in the process of making textiles. His Untitled (Weaving cotton cloth for sarong) is very harmoniously composed and has been carefully crafted to emphasise the beauty and dignity of the sitter. Elements from the surrounding landscape in the background appear in soft-focus, forming a natural frame around the central subject: the weaver at her loom. The woman’s vertically striped shirt rhymes with the diagonal lines of thread on her loom, in a manner that is both aesthetically pleasing, and implicitly suggestive of her intimate bond with her medium. Cephas is celebrated as the first professionally-trained Indonesian photographer, and many of his photographs depict subjects which he would have regarded with great reverence, such as Borobudur and other ancient temples of Java, as well as the Yogyakarta sultans and other esteemed local elites. This sensitive portrayal of a woman weaving a sarong similarly conveys the photographer’s deep respect for the subject.

The photograph itself is a very fine work of art, but the cloth woven by artisans such as the woman Cephas depicts above are also highly artistic in nature. The intricate patterns of batik and other Indonesian textiles take centre stage in many of Cephas’s photographs, such as a studio portrait of a barefoot woman carrying an open parasol. The pose and use of props in this image is strikingly similar to photographs taken in Myanmar, for example Studio Portrait of a Burmese Girl, created by an unknown maker. While both photographers have carefully overseen the composition of their fine works, the exquisite artistry of the textiles depicted has also been carefully overseen by anonymous women. Scholars such as Ariella Azoulay and Abigail Solomon-Godeau have also emphasised the collective, social nature of photography. They have argued that the people depicted in images, as well as the later users of those images, may play an equally important role as photographers in shaping the meaning of photography. The makers of these textiles may also be considered to have contributed to the meaning and impact in these images, alongside the male photographers.

In Myanmar in the 19th century, in addition to making textiles, many women also studied literature and other subjects. Education for women expanded exponentially under British colonial rule, as Buddhist monastic schools were steadily outpaced by co-educational schools that taught in English. Gwendolen Trench Gascoigne’s impressions in Among Pagodas and Fair Ladies are confirmed by historical records. Eventually, this and other transformations led to the emergence of a feminist nationalist movement in Myanmar during the early 20th century, in which the writer Daw San (the pen name of Ma San Youn, b. 1887, Myanmar; d. 1949, Myanmar) took a prominent literary role, as studied by scholar Chie Ikeya.

The life of this important political figure also intersects with the practice of women making textiles: Daw San grew up in a wealthy family that for generations had produced a kind of gold threaded embroidery known as shwe chi hto. The family was patronised by royalty and other elites seeking extravagant tapestries, garments and regalia. Despite her privileged family upbringing, she would go on to write a groundbreaking story in 1918 which insisted on the inseparable nature of national liberation and women’s liberation in the Burmese Buddhist context. While Daw San’s radical views on emancipation are in seeming contradiction to her background, might her early exposure to the elaborate art of shwe chi hto, practiced by women as well as men, have played some role in shaping Daw San’s later commitment to feminism, nationalism, and the literary arts? And what might have become of the extravagant textile arts made by her family and ancestors?

The answers to these questions are unknown, and perhaps unknowable. Yet there is good reason to hope that more art made by women in this period will be uncovered, and that more studies will consider its meanings and importance in expanding our understanding of the emergence of the modern in the art of this region. After all, Daw San’s own historic achievements and significant role in the Burmese nationalist and feminist movements have only very recently been rediscovered and studied.

There are surely many more stories about women and art in the long 19th century in Southeast Asia, just waiting to be told.

References and Further Reading

On Granada Cabezudo, Pelagia Mendoza, Carmen Zaragoza, Paz Paterno, Adelaida Paterno, and painters who were women in the Philippines during the 19th century, information is drawn from: Eloisa May P. Hernandez, Homebound: Women Visual Artists in Nineteenth Century Philippines (Diliman, Quezon City : The University of the Philippines Press, in cooperation with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 2004).

On women in the Singapore Art Club, information is drawn from: Yvonne Low, “A ‘Forgotten’ Art World: The Singapore Art Club and its Colonial Women Artists,” in Charting Thoughts: Essays on Art in Southeast Asia, ed. Low Sze Wee and Patrick D. Flores (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), 104-119. Available online.

On Emma Vidal’s botanical illustration, information is drawn from: Augustine Doronila, “How a rare botanical Filipiniana came to the Baillieu Library,” University of Melbourne Collections 17 (December 2015): 14-23. Available online.

On the Bunnag sisters and other photographers who were women in the court of King Chulalongkorn, information is drawn from: Leslie Woodhouse, “Concubines with Cameras: Royal Siamese Consorts Picturing Femininity and Ethnic Difference in Early 20th Century Siam,” Trans Asia Photography Review 2, No. 2 (Spring 2012). Available online.

On Thilly Weissenborn, information is drawn from: Anne Maxwell, “Thilly Weissenborn’s Luminous Touch,” in Garden of the East: Photography in Indonesia 1850s-1940s, ed. Gael Newton (Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2014), 76-79.

On Beth Ellis, information is drawn from: Gerry Abbott, “Introduction,” in Beth Ellis, An English Girl’s First Impressions of Burmah (Bangkok: White Orchid Press, 1977), vii-x. Ellis’s 1899 publication is available online.

On the importance of the people portrayed in photographs, see: Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography, translated by Rela Mazali and Ruvik Danieli (New York: Zone Books, 2008). See also: Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

Gwendolen Trench Gascoigne’s Among Pagodas and Fair Ladies: An Account of a Tour Through Burma (London: A.D. Innes and Co, 1896) is available online.

On Daw San, information is drawn from: Chie Ikeya, “The Life and Writings of a Patriotic Feminist: Independent Daw San of Burma,” in Women in Southeast Asian Nationalist Movements, ed. Susan Blackburn and Helen Ting (Singapore: NUS Press, 2013), 23-47. Available online.