Out of Isolation: Tomorrow's appetite is what we have on offer for today

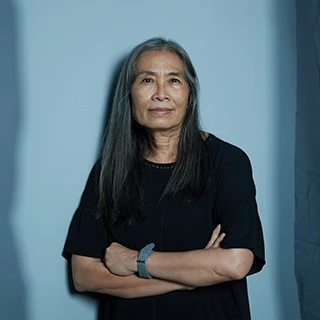

"The dilemmas and the lived experiences which I have encountered continue to process and shape my work." In this article, artist Phaptawan Suwannakudt shares vignettes from her life that continue to shape her artistic practice, which has its foundations in traditional Thai temple mural painting.

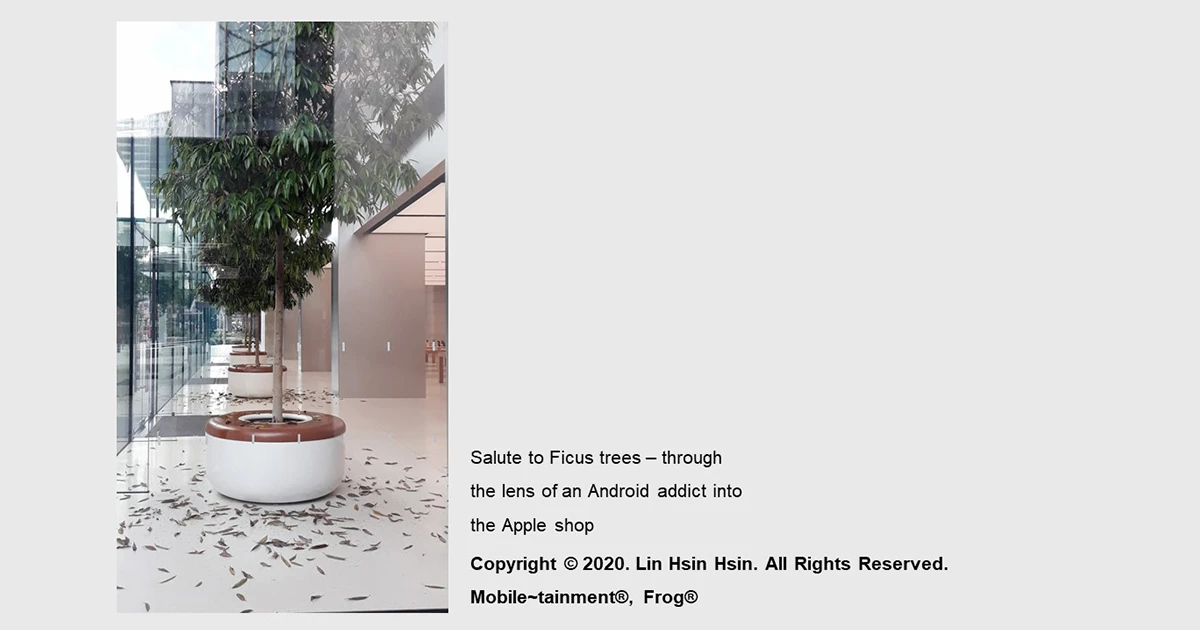

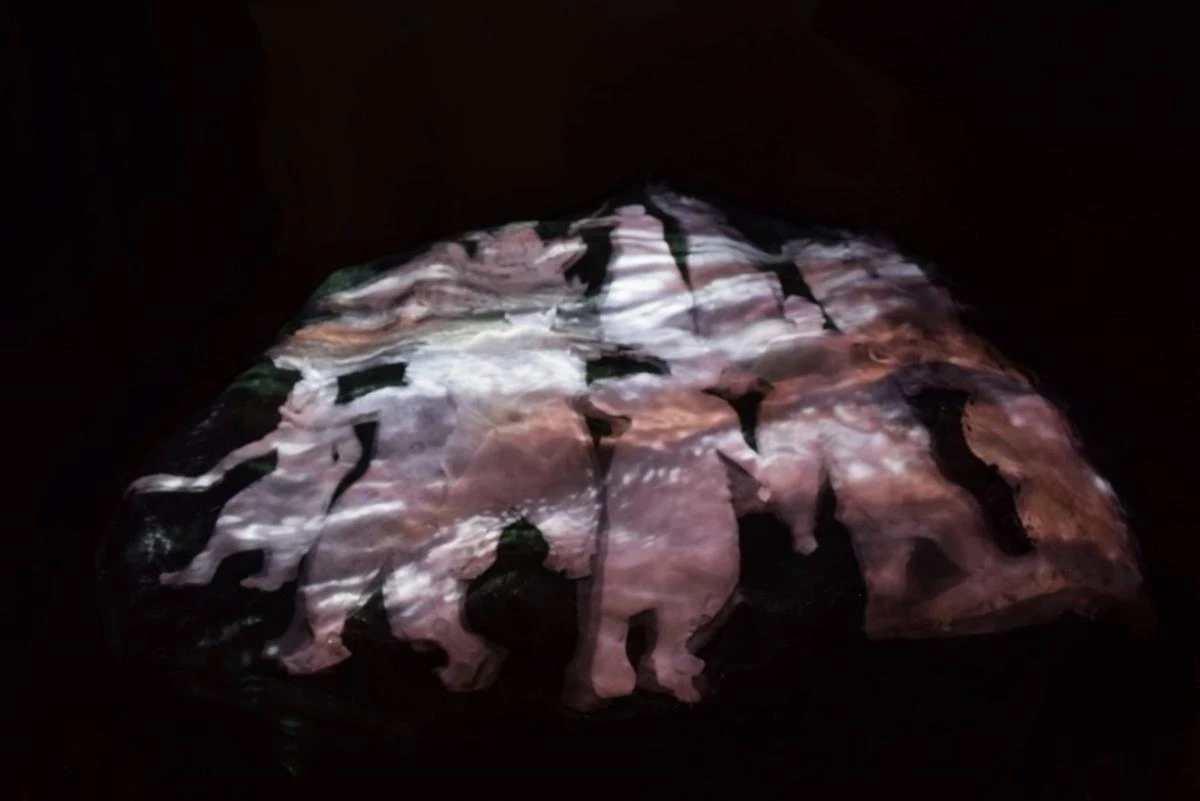

Leave

Acrylic on canvas and perspex sheets

Installation view at 100 Tonson Foundation, Bangkok, 2020

Photo by Sypatra Srithongkum. © Tonson Foundation 2022.

I was seven when I spilt boiling rice, scalding my legs from the hip down. I was standing on top of a large jar and slipped, causing one of my feet to knock over the boiling pot on the nearby stove, which then landed on top of me. My mother hurriedly took me to the hospital, where they lifted me onto the gurney. I was lying on my back when I suddenly saw the ceiling lights moving towards the back as the gurney was manoeuvred through hospital veils and doorways. Someone prompted me to start counting: one… two… three… four… Then at the count of five, the train of neon tubes stopped moving and sank into the pit of darkness.

When I came back to my senses there was a child, about my age, wrapped with bandages in the bed next to mine. Her name was Mali. I heard the grownups talked about how Mali rolled over and knocked over an oil lamp while she was asleep. The oil lamp started a fire that burnt through most parts of her body. The next time I woke up Mali was no longer next to me, and neither was her bed. I wept through the night. How would I be able to recognise her when we met outside the hospital, when I never got to see her face behind the bandages?

For two weeks, it felt like I was drifting in and out of cycles of slow-moving water in shades of black and grey. It looked like the Chao Praya River viewed from the sky. There was also something that looked like a line of black string; it had something the size of an insect attached to it, swimming along the waves of the stream. The slow movement echoed the rhythm of my heartbeat. Was it my own body which I saw from up above? Or was it the shadow following my body which was flying from the sky, in the dreams which I had no control of. Four… three… two… one… four… three… two…one … four… the visual cycles and rhythms kept repeating.

After the hospital I spent most time on my own, in the sandpit under the sala of the temple where my father painted murals.1 It was here where I had the company of picture books and manuscripts to comfort me. The daily routine of monks chanting at daybreak was soothing. I gradually absorbed the practice of living in the moment through being aware of the body and mind. At home, I would lay on my back in the shallow cavity underneath the stairs while the wound was still covered with dressing. I was satisfied that I had all the names for the eight empty snail shells I found there, discarded by their overgrown bodies. I looked up to the tree with its leaves the shape of butterfly wings. In silence I asked if your last life was a butterfly what would mine be? One of the names I gave was Mali. I found the same tree in Sydney forty years later in front of my daughter’s high school. The same tree greeted me when I opened the window from the room in which I stayed during an art residency in Chiang Mai the following year in 2014.

Chiang Mai was where my mother was born. She had already begun losing her memory when she asked me, out of nowhere, in Chiang Mai dialect, to take the longans from the tree in her garden and sell them at the market. I produced the work for the exhibition Retold-Untold Stories (2014) during the residency, in response to her wish to come home. The Lanna alphabet, filled up with herbs and spice bought from the market my mother referred to, lined up across the floor, infusing the air with fragrant aromas. The characters formed a poem in Lanna, which the late Mae Chantieng had recited to her daughter when she was a child. I was supposed to meet Mae Chantieng, then aged 95, when she suffered a fall the day I arrived in Chiang Mai; she passed away a few days later. The Lanna characters on the floor were actually mirrored; the poem could be read the right way round from the leaning mirror set up on the wall. While it could be read and sounded out, it did not mean much to most locals, particulary those from the younger generations. The formal education system in Thailand only has lessons in the Central Thai language.

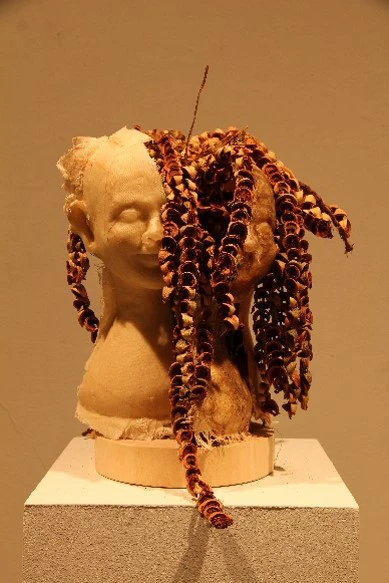

Phaptawan Suwannakudt. There, There. 2014. Fabric, resin, herbs, organic materials, dimensions variable. Installation view at the exhibition Retold-Untold Stories, 2014, Chiang Mai University Art Centre, Thailand. Photo by Aroon Peampoonsopon. (1) |  Phaptawan Suwannakudt. There, There. 2014. Fabric, resin, herbs, organic materials, dimensions variable. Installation view at the exhibition Retold-Untold Stories, 2014, Chiang Mai University Art Centre, Thailand. Photo by Aroon Peampoonsopon. (2) |

The next time I went to see my mother was in 2016. I chose to undertake a one-month residency at Sam Rit, a district in Korat.2 King Rama IX (1927–2016) had recently passed away, and the nation had declared a period of mourning; Thais had to wear black at ceremonies, in government offices and on a day-to-day basis. It was not mandated, but there were reports of people wearing other colours being attacked physically and verbally. For my mother, black clothes were taboo and carried a death curse, and were not to be worn when visiting someone ill. To avoid the moral conflict of wearing colour, I had to slip into the bathroom to change from black to a different colour when I travelled to Bangkok to see my mother. Three years later, I visited her for the last time, and whispered in her ear, Do not worry mama, please feel free to go if it is too much to stay. She passed away three months later in June 2019.

The residency at Ban Sam Rit in 2016 was when I encountered the legendary monument of the Toong Sam Rit Battlefield. The monument depicts two women warriors, standing upright and carrying weapons among other figures armed with swords, chevrons, shields, bows and spears. At the centre was the statue of Ya Mo,3 who stood higher than the rest of the group. In front of her, carrying a torch, was her niece Nang Sao Bunleur. A historian friend of mine told me that the brief, one-line written record of the battle that this monument commemorated did not include Ya Mo, and Nang Sao Bunleur only appeared as a character in a play written almost a century after the battle. My encounter of the monument during the residency has informed my practice and occupied my studio work for the last three years.

I first started working on the group painting for the project Leave it and Break no Hearts4 (2022) in late 2019, after I came back from my mother’s funeral. I also later completed an installation work The Water had reached the Plateau in 2022, for the same project; the pandemic had started in early 2020, and the exhibition for Leave it and Break no Hearts had to be postponed till 2020, giving me time to develop another work. My works Sleeping Deep Beauty (2021), which showed at ESOK, Jakarta Biennale at the STOVIA Museum of History of National Awakening, Indonesia (2021), and RE al-(re)-g(l)ory, which was featured in the exhibition The National: New Australian Art (2021), at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (2021), were developed during this time.

The first statue of Ya Mo was raised at the centre of the Korat city in 1934, and has been used as the basis for myths and oral tales of magic and wonder. It is believed that a non-native Korat who went under the Chumpon Arch would end up either marrying a native Korat—this person would then stay on in Korat—or take one away through marriage, based on whether one turned towards or away from Ya Mo. It was unknown when these beliefs started gaining traction; today, they continue to attract visitors—mainly men—hoping to get lucky by going through the Arch daily. Additionally, the vocabulary surrounding this monument and its narratives apparently includes the gender-specific word used to address men.

The later monument, erected at the location believed to be the site of Sam Rit Battlefield, was located near where I stayed, an hour drive from Korat city. It included not only the figure of Ya Mo5 but also her niece, Nang Sao Buleur. The latter’s name was first mentioned in a book6 in 1905 recording unidentified oral tales. The statue of her figure was raised in 1986 when General Prem Tinasulanont (1920–2019) was the Prime Minister of Thailand.7 The monument with the depiction of the battlefield was raised as recently as 2000,8 on the site of the battle. The community stages an annual ceremony on 4 March, with a dance procession in which rows of women in uniform perform, suggesting that they are preparing to go into battle to fight for their homeland. The myth surrounding the site is that during this annual commemoration, someone in the village would die on the day that the ceremony takes place.

Whilst I stayed in Sam Rit village during my residency, a lady told me that one night, a house had sunk into a salt field where there had been a salt-processing factory. The ten kilometre-long-road had no public transport. The nearest public healthcare facility only served basic needs and was located 26 kilometres away. I casually asked my guide what if I had a snakebite; he shrugged in silence as an answer; he had lost his father in an accident on the road before he turned one. One day I followed some sounds and found a duo performing Phleng Korat.9 It was commissioned by a teacher who had just been promoted, fulfilling what she prayed for at the monument of the two lady warriors. I placed some banknotes by the vocalists as an appreciative gesture for the live performance, especially since the performer included me by adding “Phaptawan from Sydney” to their lyrics. I also recorded their voices and mixed it to create an underwater effect. The soundtrack was added as ambient sounds to two of my works, Sleeping Deep Beauty (2021) and The Water had reached the plateau (2022).

I was grateful that in 2018, Samak Kosem and Patrick Flores agreed to engage in the collaborative project Leave it and Break no Hearts10 with me. The title relates to the dilemma I was facing with the community in Sam Rit: whether I should go along with the lies and not speak the truth. More importantly, how could I raise something taboo and break their hearts? Part of this six-month long project at 100 Tonson involved community events, one of which was my proposition to revisit the sites of the monuments with a group of academics and writers, creating a safe neutral space whereby one could observe the myths, narratives, rituals and beliefs within the community in Sam Rit village. One such participant was Pramote Pakdeenarong, who discussed his research on how the song Phleng Korat was derived from Phleng Gom (เพลงก้อม). The latter belonged to the peasant community and was performed as a vocal duet, often with humour added through improvisation; it also featured the use of erotic words in local dialect, which revolved around the nature of fertility and reproduction. It was believed that Ya Mo had enjoyed the performances, and nowadays, the Phleng Korat is used as a votive song,11 offered to the monuments of Ya Mo. For Phleng Korat, the words and music are derived from formal and ceremonial language, which is more suitable for Ya Mo, who was a lady at court. This tamer version of Phleng Korat is more commercialised, and individuals who wish to improve their wealth and lives often commission performers to perform the song in front of the monument of Ya Mo.

Revisiting the monument also led me to discover the recent costumes decorating the sculptures on the monument. During my residency in 2016, the sculptures were dressed in the style used in the time of King Rama III of the early Ratanakosin (1782–1932), which had been identified and established by the Department of Fine Arts. However, the costumes are replaced each year on the day commemorating the battle.

When I visited the monument again in June 2022, the figures were mainly dressed in the Royal colours of yellow and light blue to represent Chit Asa (literally “volunteer spirit”), the unit founded by the Royal Consort. The signature pattern featuring the letter “S,” for Princess Siriwanvaree’s (b. 1987) sign, was used on each of the garments. The trip also saw the continuation of a slightly different version of the votive Phleng Korat. Now, worshippers and performers also prepared betel nuts for the spirits of Ya Mo and Ya Bunleur, for chewing.12 Later, during the community engagement program at the A.E.Y. Space art residency in Songkhla, in the south of Thailand, I visited more sculptures—both large and small—which always have offerings provided for by members of the community. The statues of the guardian demon, Thao Wetsuwan, located on the outside wall at the four corners of the Matchimawas temple,13 are offered bottles of red soda; these sculptures were added to the temple on an unknown date. According to the locals, the red soda represents blood. A lucky-cat charm at the entrance of a local speciality noodle shop was also offered a cup of red juice.

During the revisit to the monument in June 2022, Thanavi Chotpradit proposed a project around the two installations I created for Leave it and Break no Hearts. My work can be understood as being outside the practice of current Thai contemporary art, especially since my background had been in traditional Thai temple mural painting. It is no surprise that my art practice is regarded in this limited way—often, people have already decided what they are going to believe, and there is no room to discuss issues other than form and design. To me, the notion of tradition is a way to manage things that cannot be identified as new. It is true that I carried on working as a mural painter, in the footsteps of my father. However, my practice is not limited in this way since I did not receive formal art training; I do not adhere to any formula. In fact, I grew up spending a lot of time with my father as he developed his practice, when he was experimenting with his style.14

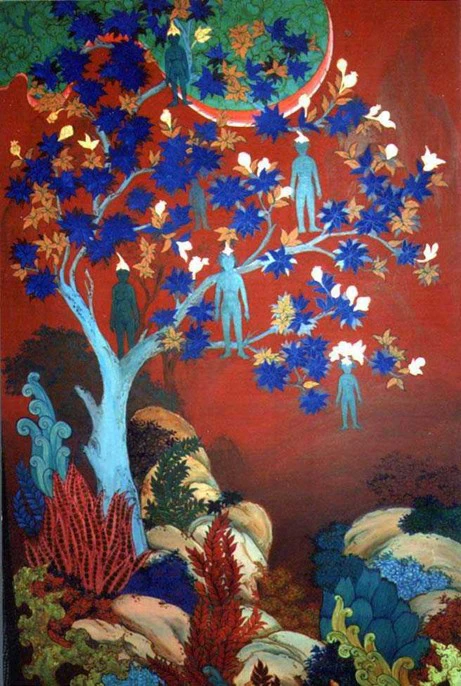

When I first set foot in Sydney in 1996, I used the sketchbook in which I had recorded my gaze of the sky in Thailand, which was now met with Australian trees; for these trees I found in Sydney, I wrote down Thai names. It may relate back to how I named the empty snail shells when I was a child. This may also be the gesture of emptying the visual field in my practice, and I began to use Thai scripts in my work starting from 2005. I sought to deliver the context of Thai Buddhist narratives in my Nariphon series (1996) and immediately changed back as I crossed over to exploring the narratives of the Buddha and the Jataka tales in the following series, Lives of the Buddha (1997‒1998).

I was unable to find room for a mural painting in the Buddhist temples in Australia. I chose instead to paint on canvas. My work provided room for me to continue pursuing context, format and terminology from outside of mural painting. It may have marked my determination to identify how I tell stories and from whose perspective I deliver them. It is important to note that I had been the first female painter to have delivered a mural project at a Buddhist temple in Thailand, which is known to be a male-only practice. Yet I could not do anything but despair when young girls were sold to brothels by their own parents, right in the community near the temple where I painted. The narratives which glorified the life and Dhamma of the Lord Buddha were manifested from men’s voices.

I started this essay with scenes which may not be relevant to my current practice. However, it may explain why I prompted my daughter, who assisted me as a videographer for Leave it and Break no Hearts, to capture the movements of a tree from the ground, and a birds-eye view of the reflection of a tree in the King Georges River as the water rippled. The slow movements of the shadows of the tree in the water, and of the tree looking up to the sky, are layered together and mixed into the rhythm of the Phleng Korat; the audio features in the installation work which depicts the monument. I recognised then how the body remembers, and how the hands, eyes and mind continue to interact with how I perceive and make sense of the world and the society in which I am part of. The dilemmas and the lived experiences which I have encountered continue to process and shape my work—this is a context which I may not have control of, but to which I can only react.

This context may be intrinsic to my veins, muscles and body, through which my memories process the work in front of me. This was how the Mandala pattern of the cosmos that my father drew becomes reflected in the pattern of the labyrinth of veils in my work Sleep Deep Beauty. This was the pattern of the ceiling at which I, as a nine-year-old child, kept staring at while lying on the floor of ordination hall at Wat Theppon temple.

The Nariphon series that I developed in 1996 was a proposition for us, as a society, to look at ourselves and ask why it is possible that the twelve-year-old girl is being sold by her parents in front of a Buddhist temple. Sadly, it was not unique case, and she was not the only girl being sold during that time in this village. In the painting, the girl in the school uniform with a fruit stem attached to her head has regenerated to have multiple bodies. She has become the fruit that we see in markets as part of normal, daily lives.

|  |  |

Phaptawan Suwannakudt. Nariphon III a‒c. 1996. Acrylic on silk. 90 x 90 cm. The works are in private collections, and the images are courtesy of John Clark. | ||

The installation of paintings in Leave it and Break no Hearts reflects the fragmented memories I have of the monument I encountered. It is also a symbolic proposition to address the broken promise that was made to the ordinary people about the basic standard of lives they deserve—these people are often overlooked. The group of paintings and obscure Perspex sheets are hung and stacked up like a stage for a performance; it is located at the far end, hung on the wall facing the entrance of the gallery, inviting viewers to enter and watch. Or indeed, it also works the other way round: it is a stadium, filled up with the characters from the monuments who are looking at us, the audience, entering; the audiences are looking at them looking back at us in an infinite cycle of normality.

Likewise, when viewers walked through the labyrinth of veils to see the work Sleeping Deep Beauty, they would not meet with the paintings of Ya Mo monument without encountering their own distorted reflections, looking at them from the reflexive film hanging along both sides. The reflections appear, disappear and reppear depending on how audiences move through the space, and the angle in which they approach. If reality does not present the truth, maybe a distorted illusion will.

Notes

- Wat Teppol temple is located in Talingchan district on the Thonburi side of Chao Praya River. In 1967 Phaiboon designed his first temple painting and trained the monks, some of whom disrobed and joined his team to work in later projects. It was a unique for me, a girl, to live in a Buddhist temple. I had the privilege because my father was the devout painter doing merit to the temple.

- Nakorn Rachasima province known to be gateway to Isan, the Northeast of Thailand

- In 1826, Lady Mo, the wife of the Governor of Korat, led the villagers in a battle and fought off the Laotian troops. This event marked a success for defence of the territory of Siam (now Thailand). Such an event has never been recorded in the Lao history. The first mention of Ya Mo as the wife of the governor was 70 years later in 1933, and did not include her participation in the battle.

- Two installation works, created by the author Phaptawan Suwannakudt and Samak Kosem, are exhibited in the collaborative project Leave it and Break no Hearts at the 100 Tonson Foundation Bangkok, May‒November 2022.

- The Thais generally refer to Lady Mo as “Ya Mo,” which means “Grandma Mo.”

- The Thai Army’s Book of Chronicle was written by Prince Boworndej in 1905.

- General Prem Tinasulanont was born in Songkhla but served in the military from Korat, where he stayed until towards the end of his life in 2019. This gave rise to the impression that he was born and bred in Korat.

- This was during the government of the unelected Prime Minister Chuan Leekphai, when General Prem Tinasulanont was Chair of the Privy Council.

- Phleng Korat is the improvised performance of a folk song, sung in the Korat dialect.

- Leave it and Break no Hearts is a collaborative project on display at the 100 Tonson Foundation Bangkok, May‒November 2022. The exhibition was originally scheduled to open in 2020 but was postponed because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

- The form and the practice of Phleng Gom faded away around the 1930s, time when the monument of Ya Mo was erected. The practice was further disrupted as agriculture gradually disappeared, with land and workers used for the base for the US troops in the Vietnam war.

- Betel nut chewing was banned in 1941 during Marshal Pibulsongkram’s formation of the nation-state.

- Wat Matchimawas in Songkhla is from the late Ayudthya period and was previously known as Wat Yaisrichan, after a female patron of the temple. However, the renovation and the renaming of the temple to Wat Klang or Wat Matchimawas (centre or middle) during the reign of King Mongkut of the Chakri Dynasty, “Matchimawas” emerged as the more popular name. The renovation added murals from the Bangkok style, and replicas of artifacts and motifs from Wat Pho temple, such as drawings of contorted hermits well-known to be from the Ratanakosin era.

- John Clark and Suwannakudt Phaptawan, “A History of Phaiboon Suwannakudt (1925‒1982),” Journal of the Siam Society 109, no.1 (2021), 1‒36