out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 Luca Lum

out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 is a special series of creative, critical and personal responses by artists on the significance of the coronavirus to their respective contexts, written as the crisis plays out before us. In "All the World's Cares," artist and writer Luca Lum reflects on how she navigates caregiving and its many time swamps during a worldwide pandemic.

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

Luca Lum (b. 1991, Singapore) is an artist and writer. Her recent concerns encompass desire, mourning, technosocialities and subjectivities, and affective atmospheres. Here, she reflects on how she navigates caregiving and its many time swamps during a worldwide pandemic, when declines across the world loop with the body’s decline.

ALL THE WORLD'S CARES

By Luca Lum

A tab to a Wikipedia article titled “Timeline of the Far-Future” lies open on my phone for months. This is a line from one of the article’s timelines, which imagines scenarios that will ensue 10,000 to billions of years from now:

One million years from now, Neil Armstrong's "one small step" footprint at Tranquility Base on the moon will have eroded, along with those left by all twelve Apollo moonwalkers, due to the accumulated effects of space weathering.2

I am on a deleting spree, removing pictures from 2019 from my phone to make room for new data, but I end up leaving a spray of photos and multiple tabs open, including this Wikipedia article, digital dog ears of my mind’s windings, resisting the narrows of linear historical time.

Time Swamp

I am in a swamp of sickness (not mine, and yet mine) that swallows all time. Amid the world’s compounded emergencies of the pandemic and slow violence of the everyday, I am caring for a diminished and diminishing life. Illness changes time, changing it for the years of its endurance. Sickness is communal, auratic; it does not need to be viral to be so. I am touched by the radius of the illness’s emanations.

This feels inevitable and essential in some ways—that in order to care, one has to be changed in this way. Any caregiving guide will advise you that it is preferable that you retain a strict leash on definitions, one of these being the condition of time, so as not to fall into a kind of folie à deux of duration, where time finds no extensions or renewals, fixated on an assumed centre, the talisman of finitude. The last thing the sick individual wants is for an enduring illness to pull everything into its orbit, drowning everything in sick-talk and its comorbidities, for the patina of loss to become a world’s central character.

In Advance of All Solitudes

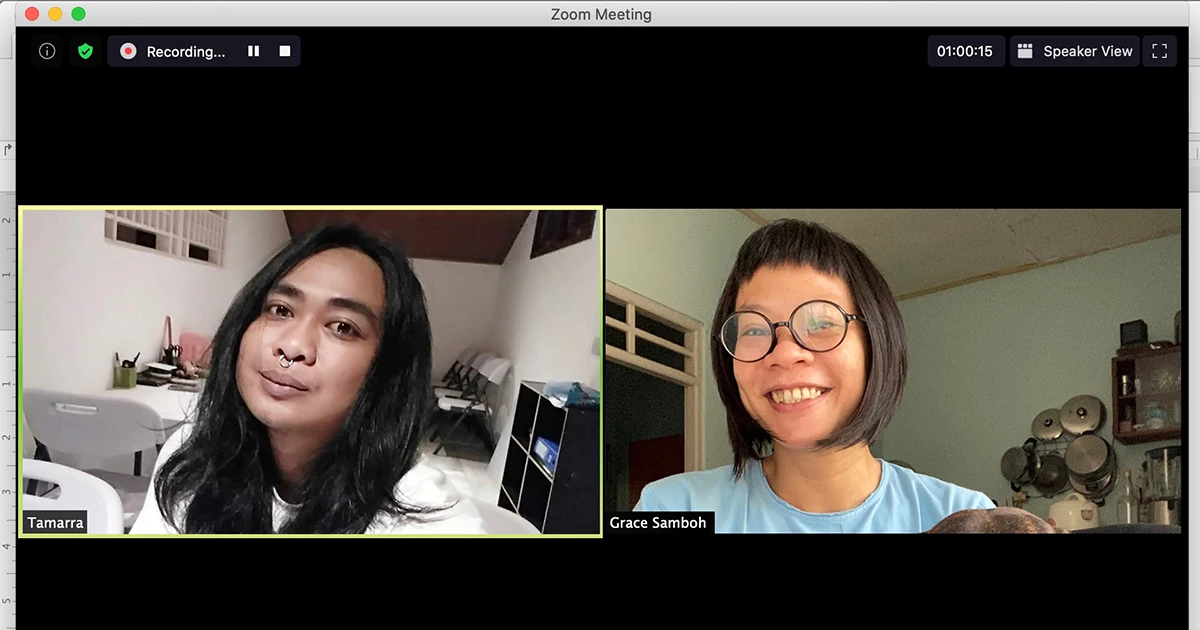

Because of sickness intimately nearby, I was in advance of the isolation and distancing curve, removing myself from social situations at least three weeks ahead of time. As a caregiver, I am sensitive to the smallest signs–a yellow tinge to the skin, the percentages of time a body spends sleeping as opposed to being awake. I am sensitive to the point of developing my own sicknesses, hypervigilant at four in the morning for the slip of a foot, a sympathetic insomniac.

Some things are a more finely calibrated antennae than others. In January and February of last year, eyes glued to updates, I tracked the programming and management class of Silicon Valley. They were among the first of the non-healthcare industries to begin realising the severity of the initial outbreak. Their familiarity with mathematical models, and keen awareness of logistical flows and the realities of contemporary connectivity, gave them greater incentive to respond to their foresight, while governments and the World Health Organization (WHO) demurred to name the pandemic, somehow caught up in the hoops of the politics of a public, world address, which ended up disregarding the vectors of virulence that multiply in miscommunicating communality.3

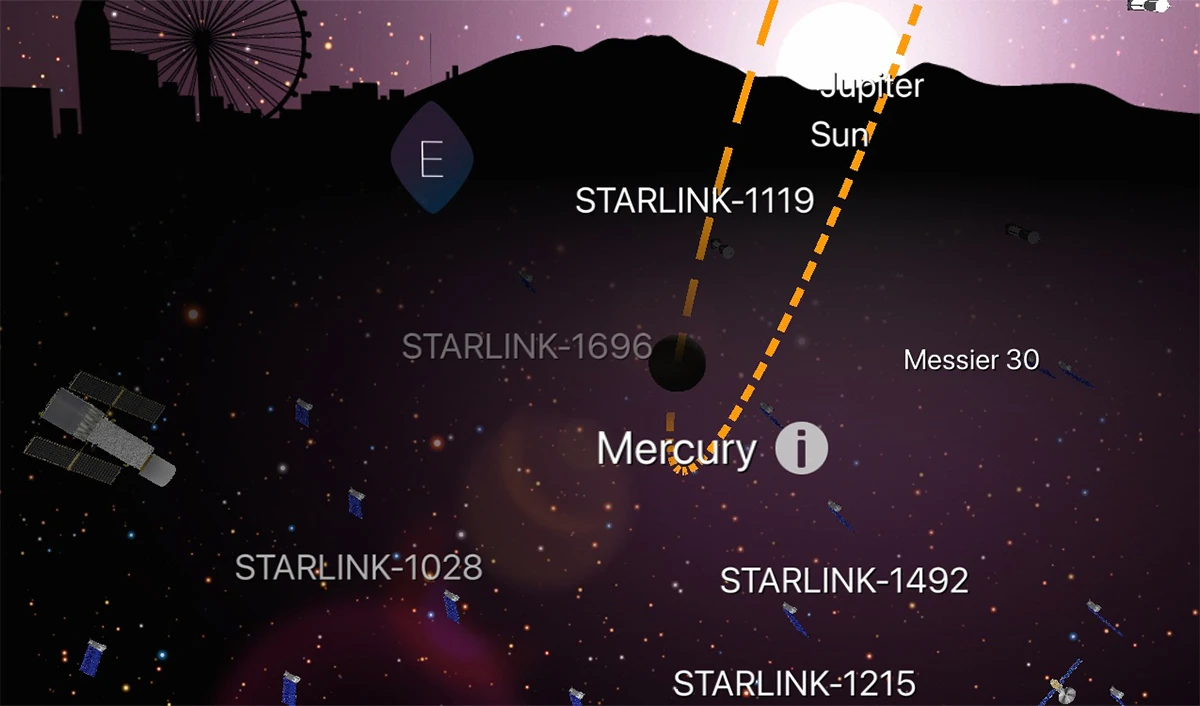

Caduceus, the two-snaked staff of the Greek God Hermes (Roman equivalent: Mercury), is often mistaken for the symbol for healing and medicine when it is really the sigil of communication, thievery, commerce, negotiation, exchange, printing and interpretation—the transport of things from one place to the next. The proper symbol for medicine is the rod of Asclepius (the Greek god of medicine and healing), entwined with a single snake, its several possible provenances including the treatment of dracunculiasis (Guinea-worm disease) and the Abrahamic figure of Moses. I think of the confusions of the two symbols and I think of the tangled lines of the medical and the communicative, engulfing and distending the other.

When the lockdowns finally started last year, I thought: so desperate and too late—but at last the world has slowed to my unmoving.

World Impasse

At first, I was not allowed to leave my home as a precautionary measure for my immunocompromised family member. The first time I tried to undo time’s private estrangements, I attended a private painting session, trying to make myself available to others beyond my family bubble, and by extension, another kind of time. As a precautionary measure, I sat apart and disoriented in the new doubled distance—the distance of world-sickness and the personal, sorrow’s fist firm in my chest. I was an aged, forgotten stone suddenly unearthed and exposed to the air.

Daily, I try to coax out of the flatness of time a chiaroscuro of meaning or insight. I sense that devoting myself to something will intensify my experience of time, enlarging it, which is important, if not for me, then for the sick person. I make rituals out of medical charts and timetables. I plan an artwork around sound, but it stalls because it requires me to imagine a space and time wider than a delimited present, and I can’t think beyond the next couple of hours; sickness can cause a vigilance where an overt attention to time diminishes duration.

I go on self-mandated runs where my tears are set off by the smallest things, especially unimpeded life—trees, other runners, dogs, and any expression of normalcy: the ability to stand upright, pump blood, to not operate constantly thinking of another body. Could crying be one way in which my body finds expansion, realising change? For an hour, from the damp cleavage of my person, the world is seen from behind the film of swollen eyes.

Care finds a sick and tender bedfellow in grief:

[...] From its Germanic origin, we get the Old English caru, meaning sorrow, anxiety, or grief; the Old High German chara and charon, meaning grief or lament; and the Old Norse kǫr, meaning sickbed. All dovetail into the modern English care. [...]

[...] It’s only been in the last few centuries that the word has taken on the meaning more familiar to modern English-speakers, as a kind of focused and concerned attention.

[...] One thing the word hasn’t lost in our time is its weight [...]4

Might we call grief a recessed aspect of care?

It is hard to speak of, difficult to surface, my condition. The world has but poor fonts for it. Roland Barthes has it hidden in a drawer, written in at least two tomes. I resent speaking of loss, as though nominating it makes loss the span of my world, but to not speak of it or make it visible creates invisible burdens and unexplained absences, as if I have made a choice to excise all commitments and relations.

In a depression, time has no defined edges; the experience is a kind of delimited present, a depthless constitution, where “the future” becomes an inert phrase, an uninhabitable, touristic image. Like its meteorological sense, depression is a kind of bad weather: a resonant, global and molecular matrix, eddying outwards.

The declines across the world loop with the body’s decline to form multiplying centres of depression. Among the many dispossessions caused by sickened and depressed time is my inability to recognize the time of another person or object. Objects shrink in substance and value. This is perhaps a finer point of alienation—the feeling of a kind of valueless world. The wound does not simply lie in feeling that a world whose material ought to hold, or formerly held potential and meaning, is now empty of it. There is a sharper, more finely constructed wound, where you sense the structures of meaning have elected to abandon you as you slip from the realm of the addressable to the non-addressable, where there is no world in effect for you.

What exists of me, or outside of me, in this moment, but attachments in disarray? To care for the one I love means losing my time to another, for another; it means for the private latches of time to undo itself. And yet another kind of enclosure takes hold: I find myself completely unable to care for the world that came before (mine), or anything outside the domestic and nuclear. There is very little that matters or holds substantiality, even the lineaments of my own body—my own wants and desires feel inconsequential. Which one came first, the time ruptures or the not-wanting?

I experience a kind of shame in this world-denial, this not-wanting. In identifying too closely to my diminished, immediate situation, there is also a blindness to the multiple times of the present. I tried for a week to contribute to a mutual aid spreadsheet but found myself unable to hold up all the other small cares of hundreds of others experiencing pain like mine and unlike mine. This “bad edge” of myself, this predicament of days, seems redolent of the self-interest of the privatised self that denies all that flows out of and into it, where one kind of pain (mine and that of the intimately sick) is disconnected from and eclipses all others out there in the fracturing world. On a certain level, I identify in myself a fantasy of control, the sense that this small sliver of the world is all I really have guaranteed and can protect, and that if I manage all my domestic and private cares, I will be alright. However, it is not nearly enough for any other times beyond this, for any further worlds.

Time in Advance

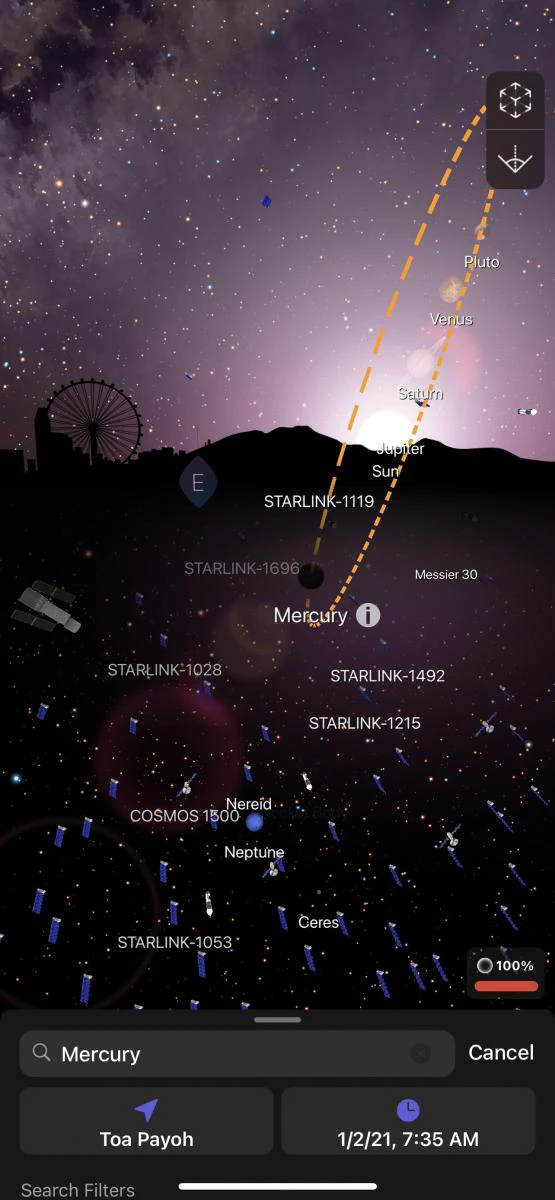

During the first year of the pandemic, major space launches by NASA, CNSA, SpaceX and the UAE, whose objectives included Mars, the Moon, human spaceflight and satellite networks, went on as scheduled, seemingly protected from what was throwing world economies into disarray to continue developments in telecommunications, surveillance networks, military applications, geospatial monitoring, celestial real estate, and future space exploration and travel.5 6

We reside on land and we sit under a sky whose conceptual future has been allotted and shaped from the time we were born and whose many pasts remain opaque in the terms of public circulation, in social knowledge. My time swamp, my sludgy intertidals, feels bracketed by these wider sets of inscriptions—multi-generational infrastructural and governmental projects of diffuse natures and scale that live in another conception of temporality entirely, and which inscript temporalities on a molecular level, nominating the terms of life, shaping the condition of the world. Whatever plans we are informed of are in some sense, already past. But who is to say we find life in them at all?

Much of this is occluded, hard to touch in the everyday, present but unrecognised. What would touching them do to deepen my time, my loved-one’s sick time, our dilated intensities and positions within a sick time? In another fantasy of mine, I find a hinge to break my own spell.

Mud to Mud

To figure out the specific and general terms of my estrangement is bodily, emotional, spiritual, social and mental—in short difficult, especially in the bad weather of (no) feeling that is at once is mine and not mine.

I am learning the multiple times of my body (multiplying my bodiedness) and I am learning how to suspend my cares momentarily to fall into another kind of absorption: of receding into the depth of a time not drawn up by schedules of pain or the schedules of predetermined life in the star charts of broadband satellites. May our cares and their losses move from the knots of our world into sightlines beyond ourselves, into something shared beyond the eclipse of anticipatory grief. Let us keep double-time, multiple scores, time unfisted, acknowledged or otherwise. Perhaps this is a shape of world, rerouted to an unexpected address.

Notes

- https://www.starlink.com/

- Wikipedia contributors. “Timeline of the Far Future.” Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_far_future; the source that actually speaks about space weathering is: A.J. Meadows, The Future of the Universe (United Kingdom: Springer, 2007), 81–88

- Michelle Goh, “Tech Was Ahead of Covid Curve at Every Stage, but It Couldn’t Bring the Rest of Us Along.” CNBC, 25 Dec 2020. www.cnbc.com/2020/12/25/tech-ahead-of-covid-curve-at-every-stage.html.

- Larissa Pham, “To Care.” Intimacies, 17 Mar 2020. http://intimacies.substack.com/p/to-care.

- Eric Berger, “Despite the Pandemic, SpaceX Is Crushing Its Annual Launch Record.” Ars Technica, 7 Dec 2020, http://arstechnica.com/science/2020/12/despite-the-pandemic-spacex-is-crushing-its-annual-launch-record.

- Cheryl Warner, “NASA Perseveres Through Pandemic, Looks Ahead in 2021” NASA, 5 Jan 2021, http://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-perseveres-through-pandemic-looks-ahead-in-2021.