Out of Isolation

Maria Labo: Aswang as Female Rage Transfigured

"Aswang" is a term used in the Philippines to refer to lower mythological figures; in contemporary media, it often takes the shape of a woman. In this article, artist Eisa Jocson shares insights into her ongoing research on fear, monstrosity, and the shape-shifting Filipino body, interrogating how the figure of the Aswang can be used as a tool of decolonisation. TW // sexual violence.

TW // sexual violence

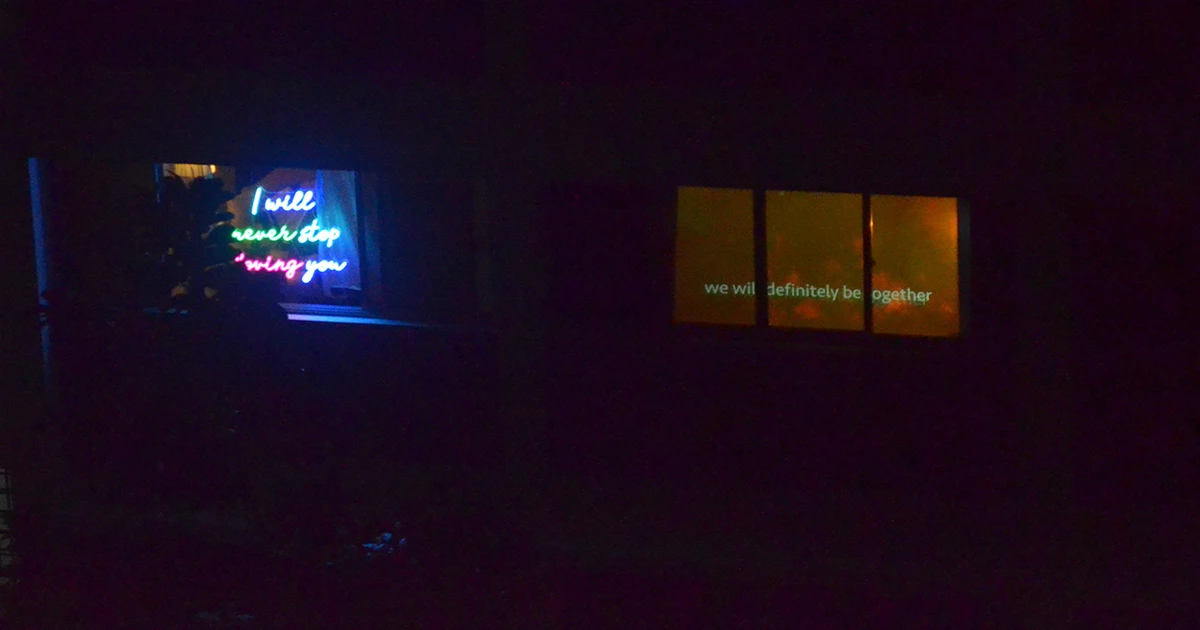

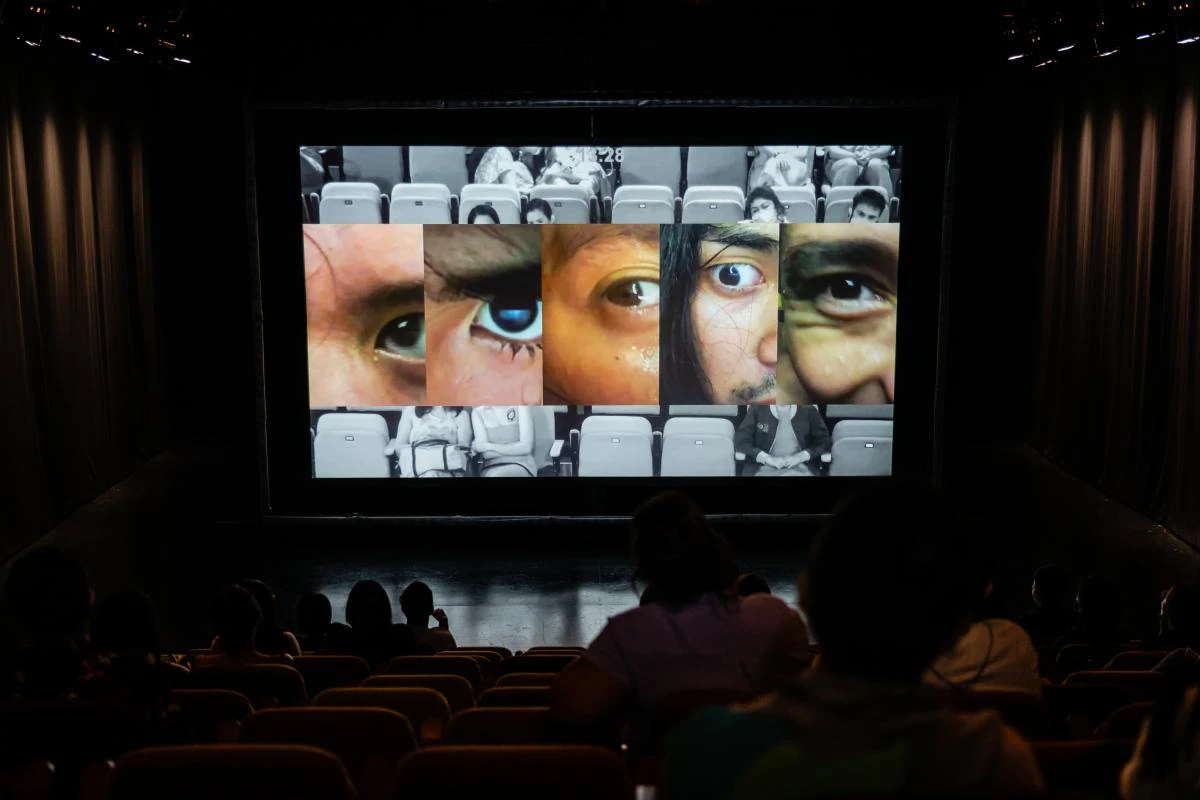

Manila Zoo is a shape-shifting sonic performance by a group of Filipino performers, live-streamed in a theater. The creation, situated in the conditions of the ongoing pandemic and ecological crisis, explores relations between man and animal, systems of labour and confinement, the politics of the gaze and the spectacle within the Disney empire, the zoo and one's own room. It is the third part of my Happyland series, which investigates Filipino labour and the performance of happiness and the production of fantasy within the globalised entertainment-service industry.

Since Manila Zoo, I’ve been reflecting on the monstrous body as a strategy for rendering the body illegible, and therefore uncontrollable and un-exploitable. The Aswang in the Philippines has become a portal for me to investigate the socio-historical context surrounding the creation of fear and its conditioning, fleshing out the entanglements between fear, monstrosity and the Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW), and the world order that it serves.

Aswangification: The Aswang as Female

The Aswang is an umbrella term for Philippine lower mythological creatures. A vessel for notions of fear, imagined and constructed, it is used to justify negative occurrences that are difficult to explain, and is also employed as a means to control people through terror.

In the Filipino horror film industry, the most popular embodiment of the Aswang is a female shape-shifting-monster: an isolated, self-sufficient old woman who has the “demonic power” to heal herself and extend her life through amulets, spells and potions. She can transform herself into anything; a beautiful woman, cat, dog, pig, bird, or even an object. She is most feared for preying on humans. The late actress Lilia Cuntapay was the poster woman for the Aswang.

The Aswang seem to have become distinctly female in form during the Spanish colonisation of the Philippines. Missionary friars, finding formidable resistance from women-led rebellions, accused It’s leaders of being hechicera (witches) or diablesa (she-devil). These women rebels were Babaylans, spiritual leaders, healers and cultural bearers, deeply revered by their communities. Mediating between the human and the spiritual realm, the Babaylan was considered more powerful than the chieftain, having direct access to the spirit world. The friars saw female spiritual leadership as a major threat to patriarchal order, and witch-hunting was a common strategy used to subjugate the new world. For the idea of the witch/she-devil to resonate among the natives, the colonisers infiltrated their concept of fear. The Aswang in the form of an old woman is a transposition of the Babaylan. She is demonised, disempowered, forced into isolation, made to be feared by her own community, and in some cases shamed and put to death. The Aswangification of the Babaylan is a severance from an animist way of life, which is then replaced by colonial notions of man’s dominion over nature.

Aswangification: Overseas Filipino Worker as Manananggal

The Mananaggal is another popular female-figured Aswang. She grows bat-like wings as she tears her upper torso away from her waist, leaving her reproductive parts and legs on the ground, her guts dangling out as she flies off in search of food. She lands on the rooftops of where pregnant women are housed, making a small hole to extend her long tongue down in order to suck the unborn fetus from the navel of the sleeping mother. She puts herself back together again before sunrise.

The Manananggal has become a metaphor for the OFW; the name comes from “magtatanggal,” which literally means “one who separates itself.” In order to sustain themselves and their offspring, both Manananggal and OFW have to violently tear themselves apart: the Mananangal from her lower half and the OFW from their home and families to work abroad.

The Manananggal has evolved to separate at the waist (rather than the head), leaving their reproductive part and legs on the ground. The Spanish, having encountered native women with bare torsos and multiple partners, imposed their morality and demonised the female body. It is speculated that the separation at the waist was to disempower female sexuality—women are shorn of their reproductive capacities.

The Aswangification of the female form is a patriarchal tool of female oppression and misogyny. The Aswang is the feral savage to be hunted and domesticated; through Aswangification, the female body becomes a site where fear is projected, violence is enacted on, replicated and affirmed. The notion of Aswang as female is used to disempower women in the community. The process is necessary in forming the colonised, exploited Filipina, one who is pious, gentle, submissive, patient (self-sacrificing). With this, the female body has lost its sacred role in society and is pushed into the domestic enclosure, where it is valued for its reproductive labor and tasks such as cleaning, cooking, giving birth, and taking care of children and the elderly. Aswangification paved the way for the extraction and exploitation of women’s labour to serve a patriarchal, capitalist world order.

Aswangification: Maria Labo

I first encountered the urban legend of Maria Labo, an OFW turned Aswang, when I was creating ‘Epic of Darna’ by The Filipino Superwoman Band, in 2019. We were attempting durational singing of excerpts from popular songs that informed Filipino Womanhood, and realised that the name “Maria” figured into many songs, from church hymns to those in Mexican telenovelas. Maria aka Mother Mary has become the prescribed/enforced performance of femininity by the Catholic church; a mother who sacrifices her son for the salvation of humanity is a fitting template for sacrificial love/labor. This notion of sacrifice is an important element in the state-sponsored labour export programme, initiated by President Ferdinand Marcos in 1970s.

Maria Labo’s story is a Visayan contemporary urban legend that started in the 1990s and continues to evolve to this day. Maria, a mother driven by the need to provide for her two children as they could not survive on her husband's income as a policeman, decides to work as a domestic helper in the Middle East. During her time as a domestic helper, she is gang raped. At the hospital, her friend, another Filipina domestic helper, passes her Aswang powers onto the unconscious Maria. Maria returns to the Philippines in an unstable psychological state. One night, her husband comes home to a feast that Maria had cooked. The husband, while eating, asks for the children to join them. Maria points to the container and the husband discovers that she has killed and cooked the children. In his fury, he tries to kill her but only manages to hack her face. This is how she came to be called Maria Labo—"labo” is to hack with a big bolo/knife. Maria managed to escape her husband, and is believed to be hunting for human prey in different parts of the Visayas. She has been the subject of a radio drama and is widely discussed and feared among townspeople. She is rumoured (among other gossip) to be a manicurist by day in Iloilo.

What is evident is the systemic and continuous violence inflicted on Maria Labo; to be separated from family in order to work for a decent wage in a foreign country, gang raped, made an Aswang without her consent, to kill and eat her own children, hacked by her husband and finally feared and hunted by the community. This update in the Aswang narrative that includes the contemporary realities of OFW, particularly that of the Filipina domestic helper, reflects the continuation of female oppression, and the extraction and exploitation of their labours.

Maria Labo: Aswang as Portal

I’ve been contemplating the Aswang as a portal and a decolonial tool in the context of the Philippines, and considering how it may allow us to reclaim agency in transforming the Filipino imagination, and consequently our lived realities.

Unlike the OFW that is likened to the Manananggal, the urban legend of Maria Labo, an Overseas Filipino domestic worker literally becomes Aswang. I want to shift our perspective of the Aswangification of Maria Labo as an emancipatory transformation. Her experience of systemic violence transfigured her into Aswang. By becoming Aswang, she is liberated her from the bonds of conventional familial and societal duties and constructs, extricating her from the exploitative system of the global service economy. She ultimately turns against her oppressors, humans, by attacking and devouring them.

Maria Labo embodies female rage. She represents revolution and subversion, summoning us to break out of our subservient Mary-fied shell and unleash our transfigured rage. It is after all, captured in the meaning of her name, Maria Slashed; the task is to hack open Maria. Her wound is a portal to our depths and a crack to unleash what has been repressed. I see the Aswang as Kali-like (Kali is the Hindu goddess of ultimate power)—a ferocious, bloodthirsty female with an outstretched tongue. She is a symbol of the destructive-creative force of Nature, abolishing man’s delusion of supremacy.

By hacking open colonial demonification, the Aswang is our Babaylan. She is a medium who can help us understand our oppression and to reclaim our spiritual connection to land. The Aswang is a portal for practicing embodied transformation. Expanding far beyond the distorted image created by colonial patriarchal powers, the Aswang’s shapeshifting becomes a strategy of becoming other than human. She is a starting point for us to expand our awareness of other beings. How can we become a cat, dog, pig or tree? The Aswang is an invitation to unleash and transform our rage, to shape it into stillness and porosity, dissolving our mind-made boundaries.

Against patriarchy, the Aswang is a portal to unbounded feminine power in and around us. I am in this portal that keeps on transforming and expanding its depths and I am continuously shifting my own perspectives and uncovering possibilities of being in the context of the Philippines.