Remembering Lee Wen: The Anatomy of Dreamers

Lee Wen was a key figure in the development of performance art in Singapore. For the Gallery Children's Festival 2018, he worked closely with Vanini Belarmino (Assistant Director, Programmes) and her team to bring seminal performance works and early illustrations to a wider audience. On the anniversary of his passing, she recollects their collaborative process.

Image courtesy of Vanini Belarmino.

I had scheduled a meeting at the offices of the Independent Archive with Singapore artist, Lee Wen, the afternoon of 19 February 2018. I had been sent to find out how he felt about “translating” his wide-ranging body of work into a series of immersive, interactive and participatory works for children on behalf of the Gallery’s Programmes team. We wanted to create an exhibition focusing on Lee Wen’s life and works for the Gallery’s inaugural Children’s Festival: Small Big Dreamers.

The decision to anchor the festival's narrative on Lee Wen was informed by the wish to spotlight a Singapore artist whose work is part of the National Collection. Born in 1957, Lee Wen was still a key figure in the Singapore and international art scene. Growing up in a single parent household, his mother had been the sole breadwinner for him and his four siblings. His father had passed when Lee Wen was a child, leaving a valued library of books that fueled the young artist’s imagination.

While he embarked on a career in banking, Lee Wen was drawn to the arts. Eventually, at age 30, he left the private sector, enrolled at LASALLE College of the Arts, and became a member of The Artist Village founded in 1988 by fellow artist Tang Da Wu. Lee Wen later moved to London to pursue his studies in art at the City College of London Polytechnic, and was awarded the Cultural Medallion in 2005. He continued his education with this prestigious recognition, completing a Master of Arts degree at LASALLE the following year. Through his storied career, Lee Wen worked with various media including drawing, painting, music, installation, video, photography, poetry and performance. He is best known for his work as a performance artist; specifically, the series Journey of a Yellow Man. Lee Wen and the “Yellow Man” are now inseparable.

Yet there I was, pitching an intervention into his practice for an untried and untested idea. Pushing artists beyond their comfort zone is never an easy topic to broach. One can never be too prepared for how an artist might respond to such a proposition. But I was determined to get his agreement.

Lee Wen arrived on time, rolling through the entrance on his electric wheelchair. In high spirits, he showed me the controls that enabled him to turn his chair around. He parked on the side and invited me to join him by the door.

“Are you here as yourself or as the National Gallery Singapore?”

Momentarily stunned by the inquiry, I responded by saying, “I’m here in my capacity as a representative of the Gallery.”

This encounter signaled a positive beginning; while I was attached to an institution, Lee Wen had acknowledged my individuality in a way I found reassuring.

He noticed one of the books I had with me, titled A Waking Dream.

“I’d nearly forgotten about that,” he said.

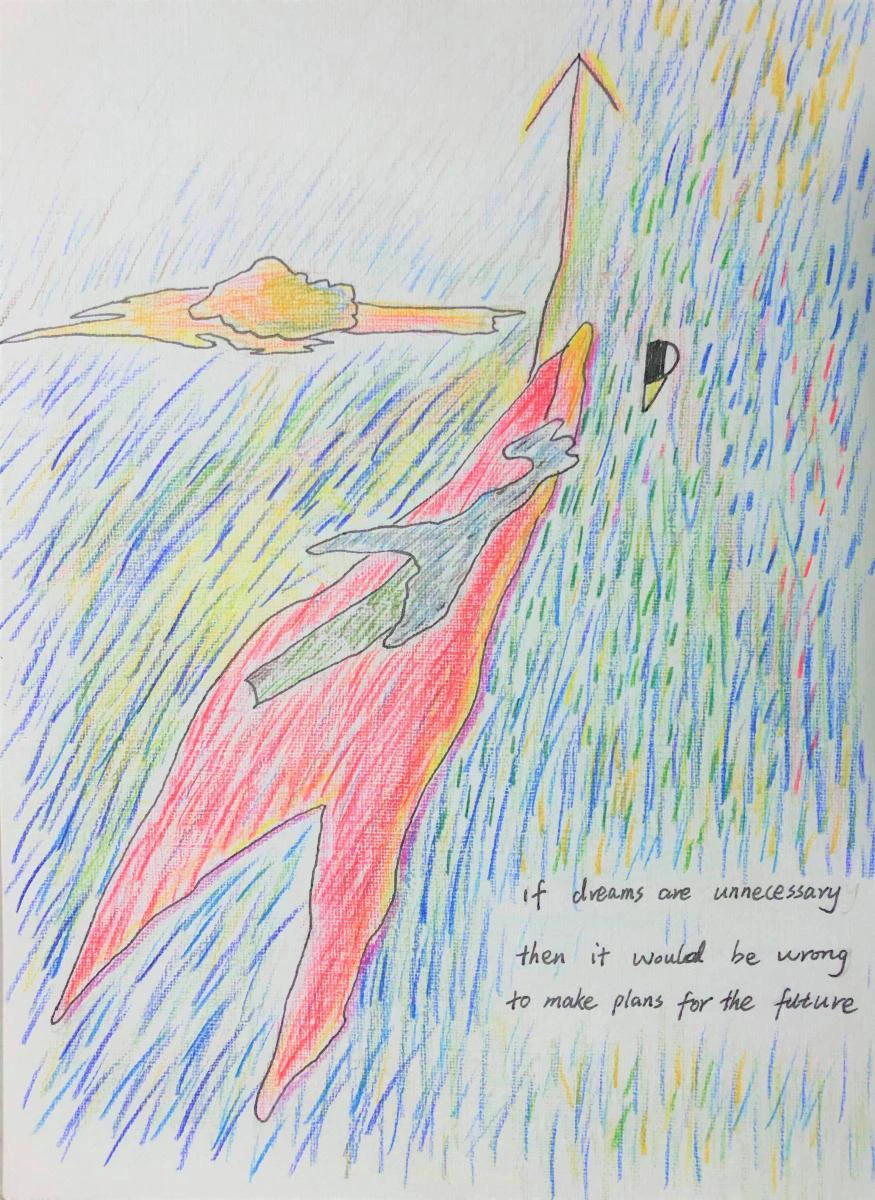

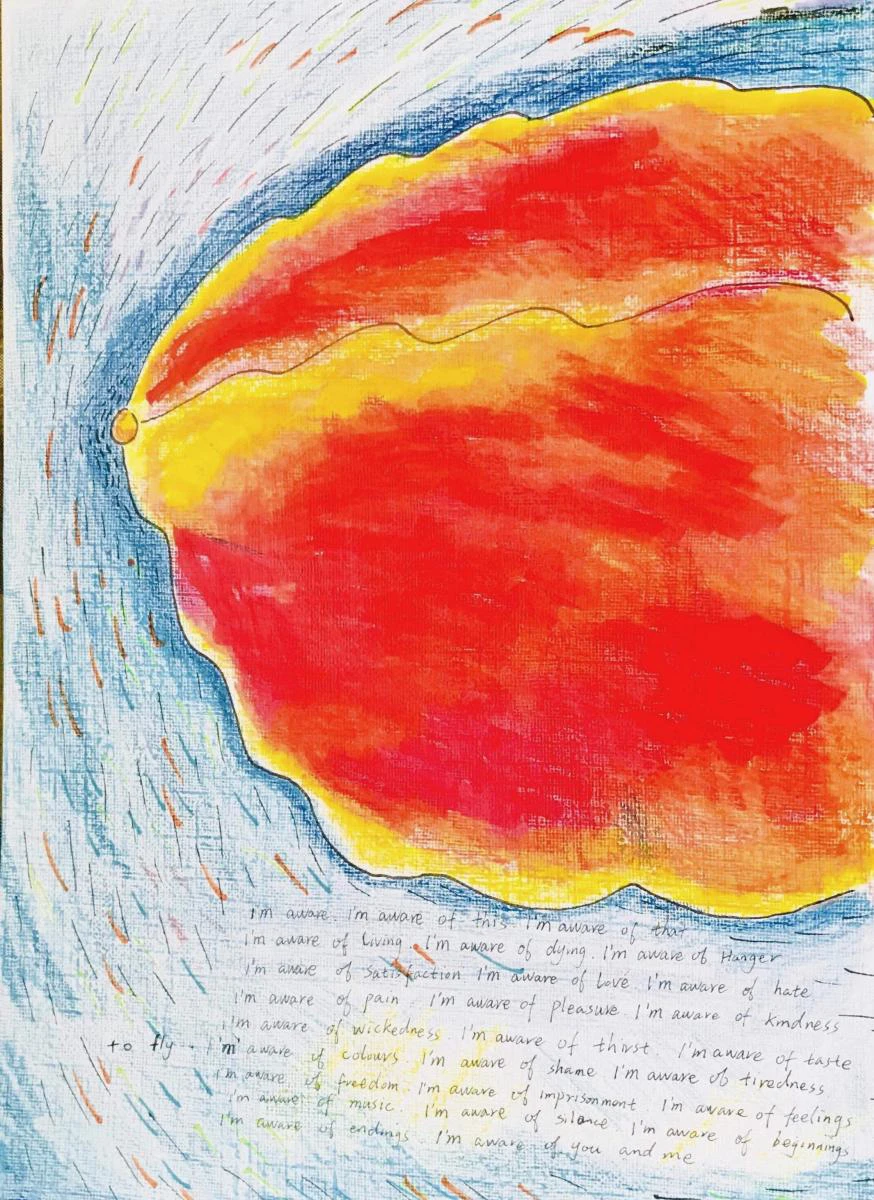

The book of illustrations and poems was published in 1981, when Lee Wen was 21 years old. It presents a journey of a child in a grown-up world. Then, Lee Wen had not yet been inducted into the art world. Neither had his seminal Journey of a Yellow Man come into existence. However, flipping through the book, the fiery dreamer who envisioned such provocative works of art is evident. Even in his make-believe world, his drawings and writings reflect a zealous spirit.

| |

“I would like to see what you are going to do. But I know this is not going to happen. It’s too good to be true,” he reflected as I was taking my leave. When I pitched the Gallery’s proposition to him, he responded with a degree of disbelief. Despite his reservations, he gave me his blessing to pursue the idea.

I left with my enthusiasm unscathed and promised to be back very soon.

Re-imagining the Singapore artist’s seminal works for large-scale interactive installations was a challenge. The team was taken back in time through three decades of Lee Wen’s work, from 1981 till 2011, from drawing through to performance art. Being in regular contact with Lee Wen gave us the courage and confidence to develop novel ideas. The process was a journey in understanding him as a human being, an artist, a collaborator and, in his words, a “soldier of culture.” Lee Wen was there when we needed him, regardless of the day. On his good days, he could hold a conversation for an hour. On other days, he would collapse without warning within minutes. All the same, he would simply ask his companion or one of us to pull him back up. As we refined the exhibition, he’d respond promptly, even sending me retraced drawings and colouring in existing ones. No matter how Parkinson’s may have affected his body, the power of his mind and spirit held him up. This held me up. This held our team up.

Lee Wen’s presence was the medium, object and subject all at once, a persona that explored themes such as identity, freedom and peace. Through ephemeral time-based performance, he placed strong emphasis on encounter, fleeting moments and contact. As his works were performed in a space that allowed immediacy between artist and audience, his practice arguably best defines genuine audience engagement. I would liken the experience to finding alone time in a public space, finding solitude amongst the company of others.

The construction of ideas for child-appropriate interactive artwork underwent a cycle of exercises in storytelling, story setting and story sharing. The Children’s Festival: Small Big Dreamers 2018’s narrative begins with the artist’s alter egos: Sun-Boy and Yellow Man. Drawing inspiration from different sources0, installations were reimagined by combining scenarios from the artist’s illustrations, paintings, mixed media installations, poems, and performances. Sun-Boy and Yellow Man each guided the audience through a labyrinth of choices.

There are so many anecdotes that come to mind as I try to write of my experience working with Lee Wen. One that stays with me is from one of the last days I spent with him. Then conducting a workshop in July 2018 for youth, he said, “I won’t stand up because I am king.” It reminded me that what we often deem as weakness can be grounded in strength. Observing him command a group of 20 students – maneuvering himself around them, sharing the grit of performance with them – was testament that real power is exercised together, whether standing or spinning with the aid of others. As we waved goodbye, we didn’t utter a word – we just shook hands and exchanged glances of assurance that we’d soon catch up.

I wish I possessed a greater command of language required to express my gratitude for his generosity. Borrowing one of Lee Wen’s correspondences, I can only say thank you for being you.

Notes

- A Waking Dream, Journey of a Yellow Man series, Neo-Baba and Anthropometry Revision were among the works the team looked at in deriving layers of stories and images for the show.