out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 Susie Wong

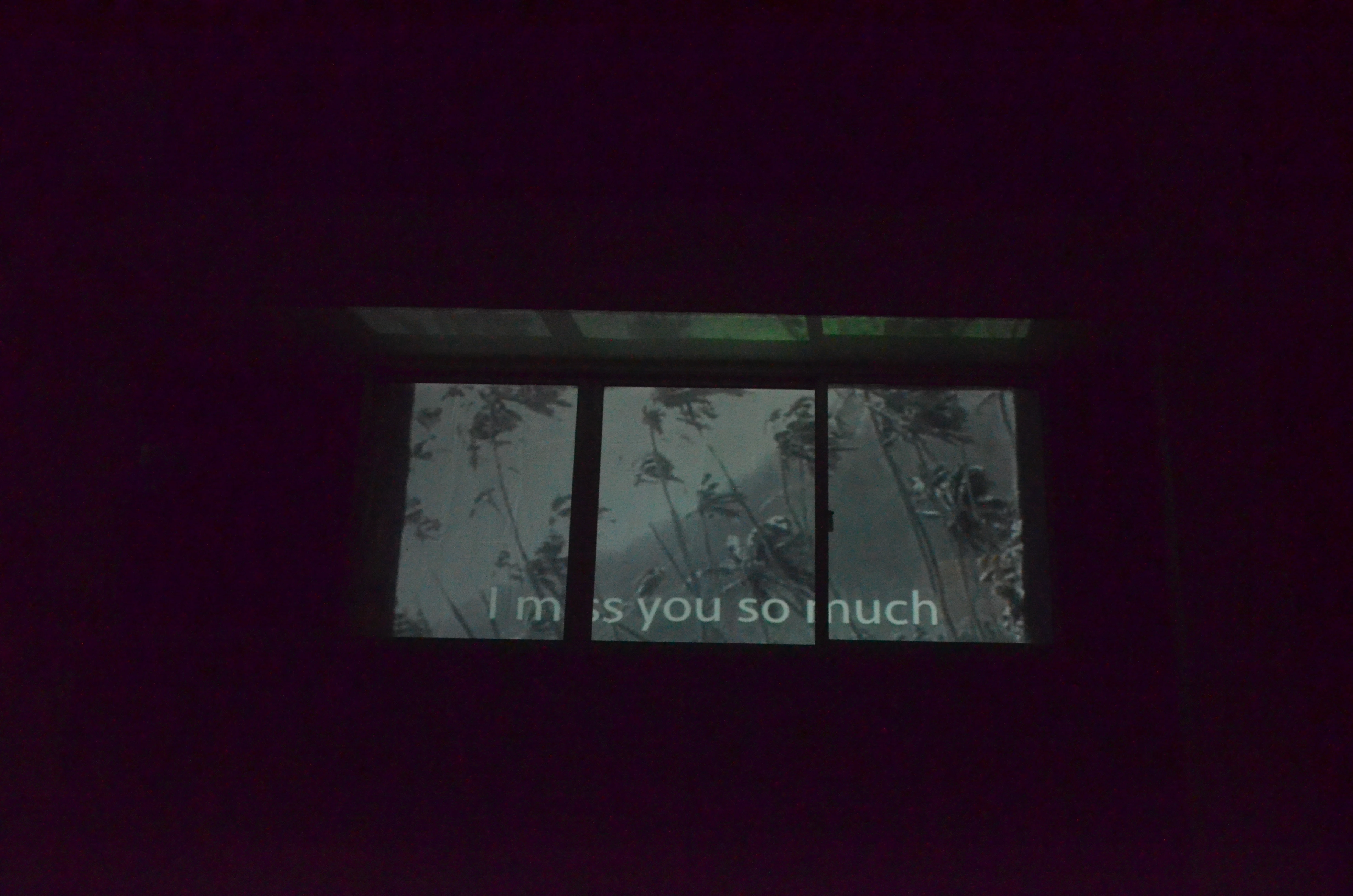

out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 is a special series of creative, critical and personal responses by artists on the significance of the coronavirus to their respective contexts, written as the crisis plays out before us. During the lockdown, filmic footage of coconut palms flashed across the windows of Susie Wong's HDB flat, attracting the attention of neighbours and curious onlookers. Find out more about her work.

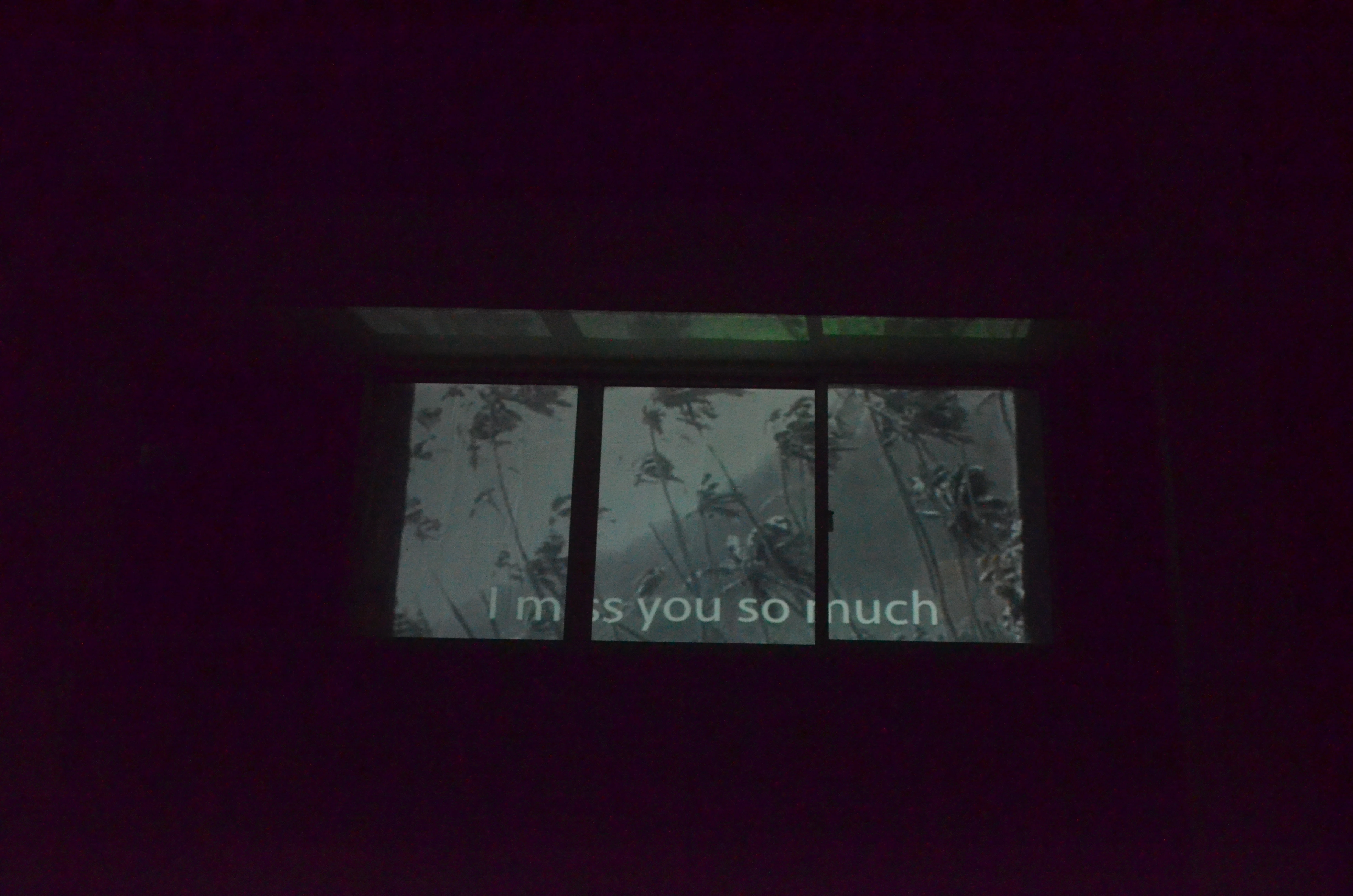

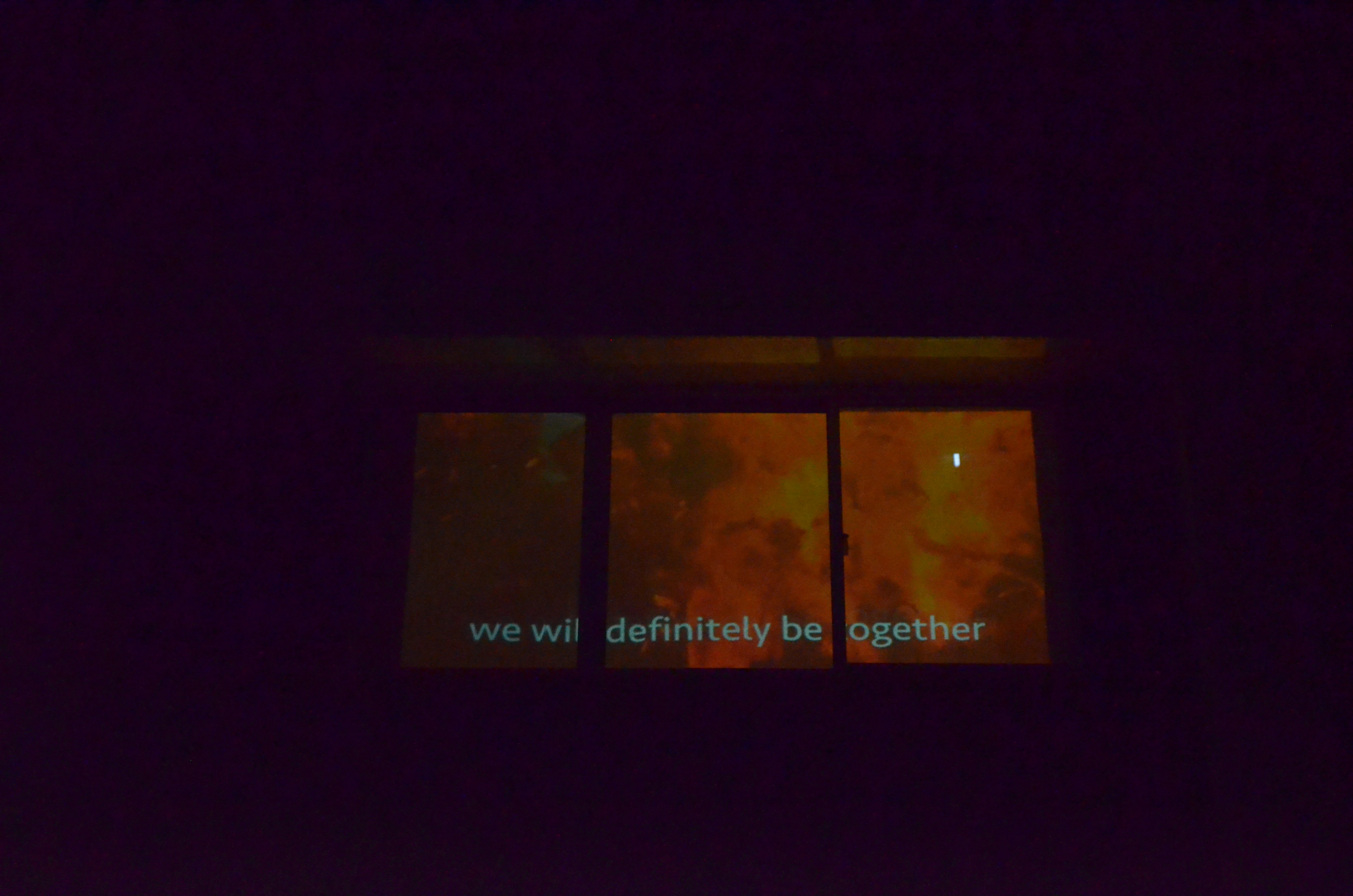

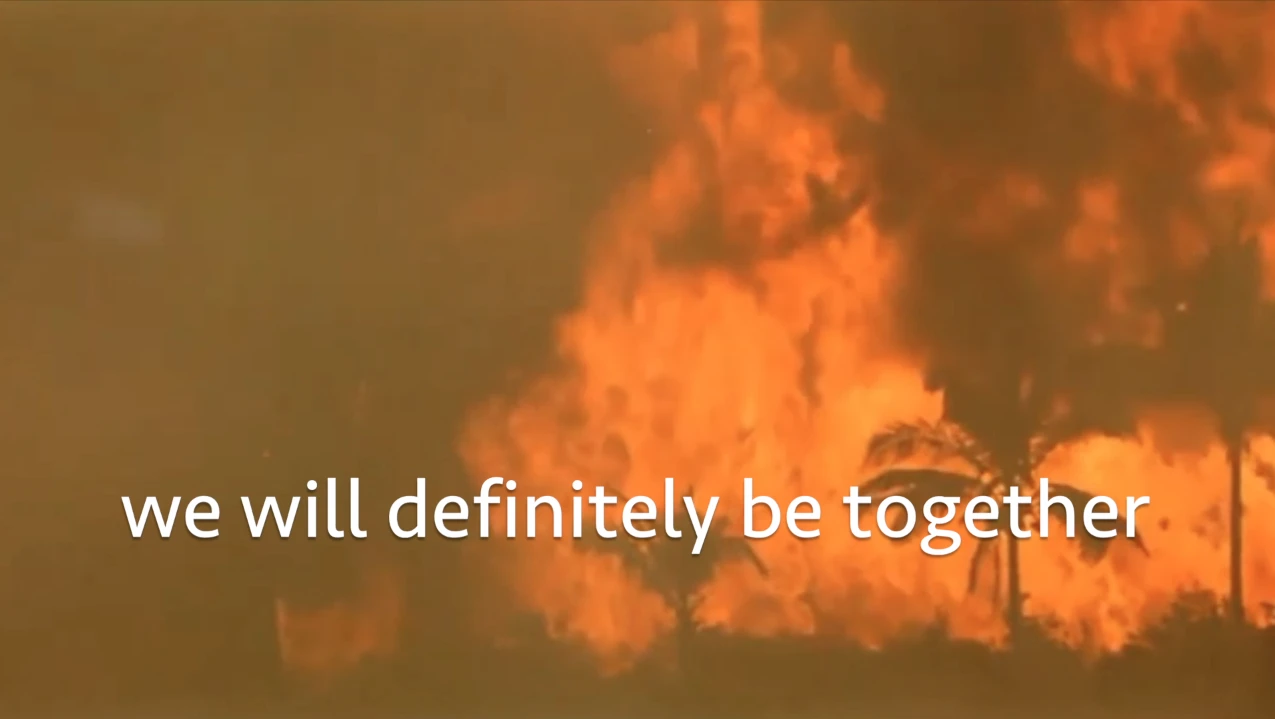

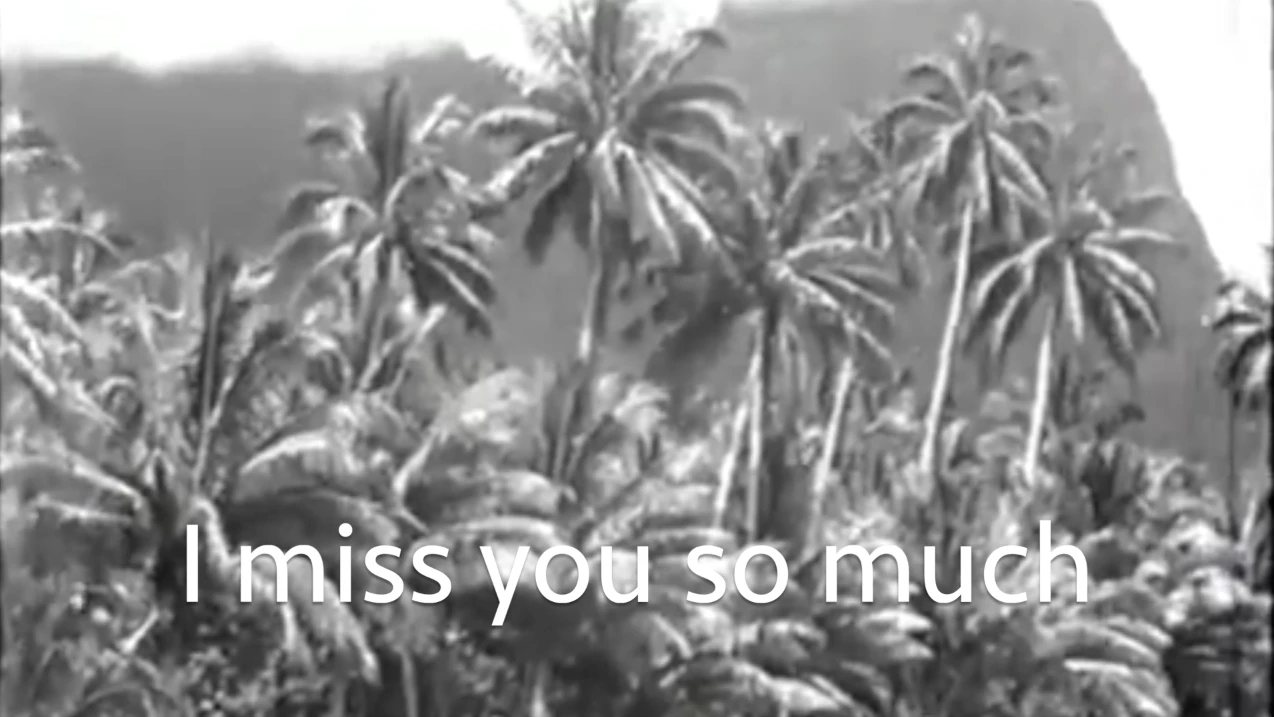

I miss you so much/ We will definitely

be together, 2020

Video, single channel, 2 min 21 sec (loop)

Image courtesy of the artist

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

During this lockdown, filmic footage of coconut palms flashed across the windows of Susie Wong's HDB flat, attracting the attention of neighbours and curious onlookers. Susie is an artist, curator, education and art writer in Singapore, whose work currently contemplates mass media and the circulation of images and its voracious consumption, appropriating images or visual references for much for her work. For the third contribution in this series, Susie Wong introduces the artwork she created.

Alone. Together.

Susie Wong

I miss you so much.

We will definitely be together.

These words, taken from a hit romantic drama, flash across filmic footages of scenic landscapes of coconut palms here. These subtitles echo a popular mantra from the COVID-19 lockdown—Alone. Together.[1] The windows of my HDB flat perform as screens over which these filmic landscapes are projected to the outside world. These coconut landscapes strangely echo the stunted coconut trees outside my house. The filmic landscapes seem to bleed into the actual landscape and, at the same time, void the interior of the flat where isolation is pronounced. They carry a fleeting message to the neighbouring community, themselves stuck in their own isolation.

I miss you so much.

We will definitely be together.

Coconut trees are often the silent parentheses for Romance

Coconut trees often act as the backdrop to Romance in films. In the colonial imaginary, the coconut tree asserts “island” as a Romantic place. In the power-coded relationships of old Hollywood movies, Romance embraces the white and native, othering one into passive despair. The island imagery is necessary for Romance, as it is in itself the intimation of desire, of longing, “nostalgia for a world apart.”[2]

To further suggest the “Otherscape,” the swaying palm fronds fade in (cross dissolve) over the screen as the scene of lovers locked in a kiss fades out. As in the strange silent scene in the The Mutiny of the Bounty, 1935.

The island Paradise

Coconut trees conjure Paradise on a tropical island. Isolated from the outside world, cocooned in the interior imaginary, the coconut-laced island in films is the paradisiacal idyll—something to long for, to yearn for, and to desire.

Coconut trees offer a filmic code for such Other places. Poring through romance films, as if bracketed by these trees, the coconut trees signify something that lies outside society.

On this island paradise lies Romance, usually bordering on the illicit, made more illegitimate by the unlikely coupling of people, and the obsessive flight from society’s rules.

In every Romance is the yearning for reunion. And the tragedy of not being reunited. These perennial stories enthral us.

Alone. Together.

My head is filled with ideas of coconut trees.

And the reality of separation

For instance, the brief five-second shot of a palm tree against a dusky sky in the film In The Mood for Love (2000), shown in the interval when the lover leaves for a tropical island (Singapore no less), means something. It symbolises a distant place, a distant void in which one gets swallowed up.[3]

In the reality of separation is the impossibility of union. Amid the utter promise of it.

I miss you so much.

We will definitely be together.

Words are repeated over and over again in Romance, as perennial tropes to “Hello, Goodbye.”

In Passage to India, as the Englishwoman, Mrs. Moore, leaves India, the boat sails in the midst of “thousands of coconut palms [that] appeared all round the anchorage and climbed the hills to wave her farewell.”[4] In the spirit of being welcomed, Charles Chauvel’s film documentation of Fiji and Pitcairn islands in the 1930s (incorporated into another Bounty film, In the Wake of the Bounty, 1933), carries in the same way, footage of beaches, lush with these swaying trees. Approached from the sea, they sing of the island Paradise.

Somehow coconut trees either wave goodbye or beckon us toward the shore. Either way, they are only visible to those who watch from outside, and it is so when they enter through the coconut gateways that they can encounter romance in its impossible interior. Romance and the Other seem locked together.

We only become aware of these thousands of sentinels when we are out at sea, looking toward the island, when we arrive or when we leave the shores.

Impenetrable dark forest

To enter the interior is to be violent.

Joseph Conrad makes an exquisite yet disturbing probe in Heart of Darkness on warships moving to claim land in another continent: “in the empty immensity of earth, sky and water, there she was, incomprehensible, firing into a continent."[5] Firing—as in Coppola’s opening sequence in Apocalypse Now (1979)—to pulverise, to annihilate, to tame the Otherscape, the unknown, the “horror.”

We are either facing the dark impenetrable forest to claim it or we are coming out of it, to escape. Or we stay.

And as with Romance, it is an impossible union, unless as in the well-known song, you “take all of me.”

All of me

Why not take all of me

Can't you see

I'm no good without you.[6]

Alone. Together.

Credits:

In the Wake of the Bounty, 1933. Produced and directed by Charles Chauvel.

Apocalypse Now, 1979. Produced and directed by Francis Coppola.

Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935. Produced and directed by Frank Lloyd.

Acknowledgments: Anmari Van Nieuwenhove, Evelyn Tan, Chelsea Chua and Gene Kam.

Notes

- On the Red Dot: COVID-19: Alone. Together., “Living Between Lockdowns,” Mediacorp Channel 5, May 2, 2020, https://www.mewatch.sg/en/series/on-the-red-dot-covid-19-alone-together/ep1/939834.

- Henrik Gustafsson, Out of Site, Cultural Reflexivity in New Hollywood Cinema, 1969-1974. (Stockholm University: 2007), 107.

- “Fa yeung nin wa (In The Mood For Love) (2000) Trailer,” Youtube, Sep 20, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aZbvP8bl1uw&list=PLfeTTh5Z_L8yzKeX3O9PXwFoE2HOLDsVm.

- E.M. Forster, A Passage to India (Edward & Arnold Co., London: 1924).

- Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (Coyote Canyon Press, 2007), 18.

- Gerald Marks and Seymour Simons, All of Me (Irving Berlin Inc.,: 1931).