out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19

Jimmy Ong with Johann Yamin

out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 is a special series of creative, critical and personal responses by artists on the significance of the coronavirus to their respective contexts, written as the crisis plays out before us. In 2015, Jimmy Ong began developing a body of work examining the figure of Thomas Stamford Raffles across Singaporean and Javanese histories. Accompanied by an essay by Johann Yamin, Ong continues to unearth these materials and Raffles as an icon in his video documenting the sewing performance, Uncursing Cotton, in the eighth piece for out of isolation.

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

In 2015, Jimmy Ong began developing a body of work examining the figure of Thomas Stamford Raffles across Singaporean and Javanese histories. Through the restructuring and recentring of Raffles’ established form, Ong’s body of work evinces a history of violence executed by the now-icon that has been wilfully overlooked. In his new sewing documentation video, Uncursing Cotton, edited for out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 while the artist was in isolation in Singapore, Ong progresses, or perhaps more accurately regresses, his sculptural work through performance. As Johann Yamin’s accompanying text explains, the continuation of Ong’s practice “resists a broader cultural amnesia towards Raffles’ violences—and by extension, the violences immanent to colonial histories.”

Jimmy Ong’s practice involves highly personal inquiries into bodily forms and queer(ed) identities, expanding into broader entanglements with regional myths, archetypes, traditions, and historical narratives. Johann Yamin works across video, internet, and installation; he is also involved with curatorial work, acts of support, and writing. His topics of interest include new media technology, optics, affect, cinema, video games, and media histories.

Uncursing Cotton

Jimmy Ong

Text by Johann Yamin

A soft body incised by tailor’s shears: hands work tenderly across limp form, deftly gouging innards and discarding scraps from an open gash. Palms push in deep, fingers prising apart, pulling away fabric flesh that obscures. Virulently-hued skin is then flayed out, gently baptised in dye, sewn up, and finally strung taut over tanning rack. Rendered nigh unrecognisable is a soft sculpture effigy of Thomas Stamford Raffles—headless and legless, its posture and crossed arms serve as the only spectral semblance of that familiar statue of the British coloniser along the Singapore River.

“When applied to body parts, basic compositional exercises, like up vs. down or in vs. out, come off as cruelly tongue-in-cheek. These simple organizing gestures cannot help but remind viewers of the actual morphology of the body—and of their living bodies in particular. […] To become aware of these particulars, one must imagine oneself unwhole, cut into parts—deformed or dead.”1

In 2015, Jimmy Ong began developing a body of work examining the figure of Raffles across Singaporean and Javanese histories—in continuation with his large-scale, figurative charcoal drawings from the 1980s, Ong’s interest in the figure of Raffles has since unspooled as drawings, installations, videos, and performances.2 Such works by the artist often involve a rupturous “un-wholing” of bodies, their meanings further inflected by the recent, fragmentary invocations of Raffles’ body during and after the bicentennial in 2019.

Just last year, a seemingly endless slew of commemorative events were launched after years of planning under the aegis of the Singapore Bicentennial Office.3 Said to mark the 200th anniversary of Raffles’ arrival in Singapore, the historiographical anomaly of a country commemorating a colonialist’s arrival must be taken alongside instances such as the 1984 speech by then-Second Deputy Prime Minister S. Rajaratnam. He stated that the government’s decision “to name Raffles the founder of Singapore is an example of the proper use of history,” while “to push a Singaporean’s historic awareness beyond 1819 would have been a misuse of history” that would “plunge” the nation into a “genocidal madness.”4

The bicentennial commemorations began with several well-publicised acts of gimmickry surrounding the Raffles statue: his form was first made "invisible" via temporarily painted optical illusion, and later made multiple when joined by other pedestalled (non-European) men formative to Singapore’s history—Sang Nila Utama, Tan Tock Seng, Munshi Abdullah, and Naraina Pillai.5 While it would have seemed natural for Singapore to bring forth Raffles’ body as its inaugurating gesture for the bicentennial year, the simultaneous instrumentalisation and decentring of Raffles’ form, then, would indicate a contoured broadening in invited approaches to the state’s method of “proper” history. By invoking broader histories beyond 1819, both the conceptual back-and-forth surrounding the bicentennial’s raison d’être and the frailty of its foundations were made manifest.6 Ong’s works involving Raffles’ body, predating the bicentennial, thus take on a prescient register when considered alongside these retroactive discursive rearrangements.7

In June 2019, at the official opening of the Bicentennial Experience showcase—the “multimedia sensory experience” that served as centrepiece to the bicentennial—President Halimah Yacob launched the book, Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore.8 Co-authored by historians Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng, Tan Tai Yong, and Peter Borschberg as a rewrite of an earlier 2009 publication, the new book’s co-publishing under the Singapore Bicentennial Office operated in tandem with the continued deployment of "700 years" as the common refrain of choice for the bicentennial commemorations, instead of the expected "200 years". Singapore’s pre-colonial Malay past, commonly swept aside and “relegated to the realm of myth” in state renderings of the "Singapore Story," had now been coupled alongside the state’s strange Janus-faced commemoration of Raffles in the nation’s historical narratives.9 The broader histories of the Malay world would be acknowledged in this rearticulation of events, yet colonialism itself and its attendant violences would never be explicitly decried. While the coloniser’s form could be prodded at and painted over, his gaze would ultimately remain as the adamantine ontological basis of this history.

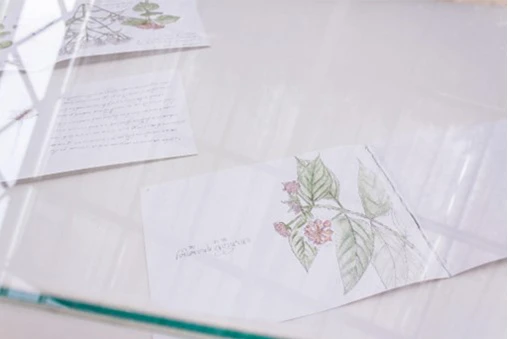

At the 2019 exhibition Raffles in Southeast Asia: Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman at the Asian Civilisations Museum, objects from Raffles’ personal collection, obtained during the British occupation of Yogyakarta, would rest within vitrines. Kerises from the fallen warriors of Yogyakarta would be placed on display within an exhibition that portrayed Raffles more akin to a bumbling “gentleman of his era.”10 One is reminded of the omission of the 1811 invasion of Yogyakarta in the two-volume The History of Java (1817), authored by Raffles himself—an erasure of violent killings, looting, and sacking of the indigenous court.11 Such figures of necropolitical sovereignty, as Achilles Mbembe writes, are so often discerned by their central project of “the generalized instrumentalization of human existence and the material destruction of human bodies and populations.”12

In Singapura, 1823, merchant Syed Yasin fled from prison, incarcerated by William Farquhar for the debt Syed owed to another trader. Upon escaping, Syed attempted to murder his creditor, killing a police guard in the process. Farquhar would assist in the attempt to arrest Syed once more—in the ensuing violence, Syed would wound Farquhar with a stab to the chest, and a sword would strike Syed, splitting his jaw from mouth to ear, causing immediate death. Raffles, unsatisfied with Syed’s demise, gave orders for the mutilated corpse to be strung up in an iron cage, paraded in a bullock cart around town, finally hung on a pole in Telok Ayer for 15 days, the body dehydrated and deteriorated.13

Corpses go unmentioned, and in this silence we sense the “ideological ruptures that open around the dead”—all that remains are attempts to fill the “yawning gaps” left by these openings.14 Sutured together from sinews of video recorded and performed by Ong during and after Singapore’s partial lockdown, Uncursing Cotton features the artist’s hands dissecting a headless, legless, soft sculpture effigy of Raffles. Here, this act of mutilation is part of an extended preparation process, with Raffles’ skin to be flayed, limed, fleshed, bated, and tanned as leather. One notes the materiality of a body rendered corpse-like, unwhole. Eschewing hard polymarble or bronze, this manifestation of Raffles is soft, fleshy—a squishy cadaver awaiting putrefaction. This body without organs, this imperial leather, now metamorphosed into something perhaps useful for the moored individual.

Current travel restrictions have prevented Ong from leaving Singapore and returning to his home and studio in Yogyakarta, where he has lived and worked since 2013. Uncursing Cotton was developed by working through existing material from the artist’s previous installations. Ong’s practice across these geographies operate through an emphasis upon Raffles’ violent role in the British rule of Java, a “sustained and epoch-changing trauma for a centuries-old society,” situating these histories alongside Singapore’s.15 Such resists a broader cultural amnesia towards Raffles’ violences—and by extension, the violences immanent to colonial histories.

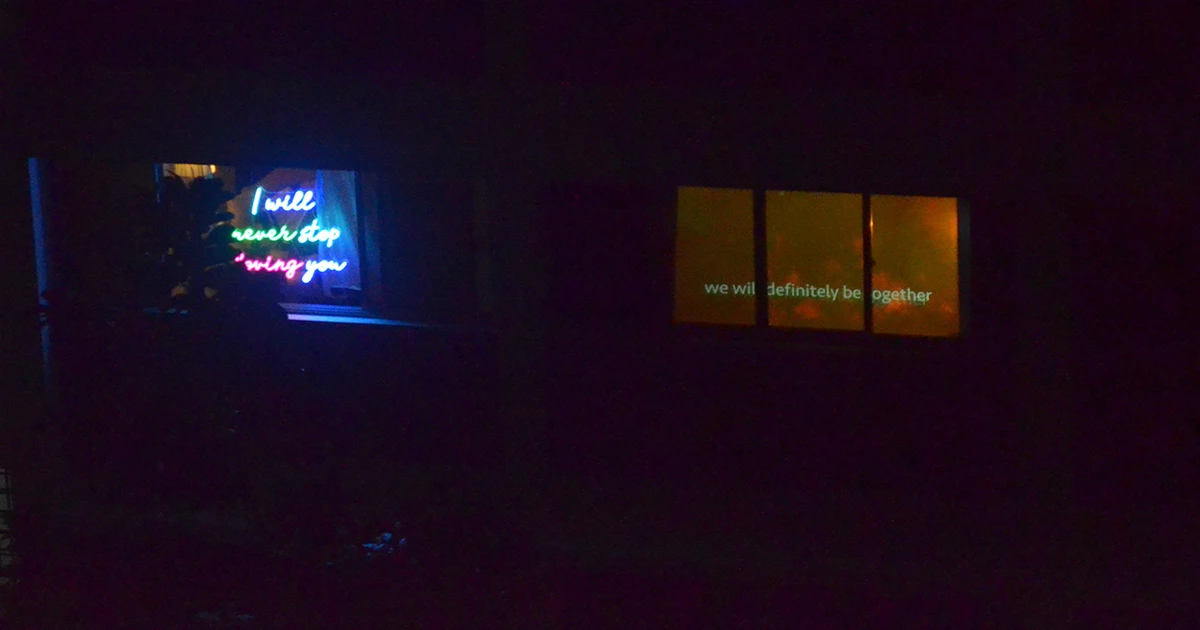

During the COVID-19 pandemic, thinking through the ostentatious performativity of previous years’ commemorations produces a stark disjuncture—it all appears unnaturally distant, both temporally and affectively. The political construction and buttressing of a consolidated historiography so often pools together, congealing as ineluctable flatness for Singapore. Even in attempts to construct a sufficiently rousing, decentralised celebration, the National Day Parade 2020 took on a sombre cadence. In pandemic time, the ill-suitedness of such grand narratives are only augmented: one wants to pull apart these monumental forms, reconfigure them as something useful for the deracinated individual.

Just as recently, discussions about Raffles’ icon have once again flared up in light of the Black Lives Matter movement and the renewed call for the felling of colonial statues elsewhere in the world. At a closed-door online roundtable hosted by The Substation in June this year, Farhan Idris, Faris Joraimi, Hong Lysa, and Liew Kai Khiun discussed Raffles’ iconicity in relation to present conversations about confronting colonial histories and figures. In addressing the contemporary relevance of the statue of Raffles, Faris notes that the disavowal of these “performative erections” need not arrive as an act of festivity, but could instead come as a quiet, powerful moment of national reflection, one that could mark the beginning of a new self-confidence for Singaporeans.16

Earlier this year, Syed Hussein Alatas’ seminal 1971 text, Thomas Stamford Raffles: Schemer of Reformer? was posthumously republished. A lucid examination of Raffles’ political philosophy and ideology, it sought to correct the predominant canonisation of the colonialist as an heroic reformer. One is drawn to Syed Hussein’s opening remark that history has been aptly defined as “the study of the dead by the living.”17 One could think of Ong’s mutilative acts to Raffles’ form as a historiographical incursion, a study of the dead alongside the ideological ruptures engendered by this body. Rather fittingly printed on every book cover of this edition of the text is none other than a photo of Ong’s recent sculptural work, Raffuse Bins/Knives Block (2019). Here, Raffles’ body is made pink, lustrous, and queer; knives penetrate his back, extending as jutting protrusions. One turns to this version of Raffles and cannot help but leave you with this view, perhaps as a parting image for now:

Postscript: The first session of Jimmy Ong’s livestreamed performance involving the soft sculpture effigies was held on 18 September. A second session will be held at 6 pm on 1 October. Follow @ayearinjava on Instagram for more information and to view the performance on Instagram TV.

Acknowledgements

With immense thanks to Faris Joraimi and Kirti Bhaskar Upadhyaya for the generative conversations and helpful comments. I am also grateful to Kin Chui and Seelan Palay for the generous sharing of materials that have been valuable to the piece.

Notes

- Mike Kelley, “Playing with Dead Things: On the Uncanny,” in Foul Perfection: Essays and Criticism, (Cambridge, MA; London: MIT Press, 2003), 82.

- The current prep-room project at NUS Museum, Visual Notes: Actions and Imaginings, develops an inquiry into the shifts and continuities within Jimmy Ong’s practice from the 1980s to the present. See also Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, Recent Gifts: Works and Documents of Lim Mu Hue and Jimmy Ong (Singapore: NUS Museum, 2014) and T. K. Sabapathy, From Bukit Larangan To Borobudur: Recent Drawings By Jimmy Ong 2000-2015 (Singapore: FOST Gallery, 2016)

- See Yuen Sin, “Plans to mark 200th anniversary of the founding of modern Singapore in 2019: PM Lee,” The Straits Times, December 21, 2017.

- S. Rajaratnam, “The Uses and Abuses of the Past,” (seminar, Adaptive Reuse: Integrating Traditional Areas into the Modern Urban Fabric, Singapore, April 28, 1984). Accessed via the National Archives of Singapore.

- In partnership with the Singapore Bicentennial Office, the former installation was Raffles’ “Disappearance” by Teng Kai Wei, and the latter, another commission from the office titled The Arrivals by Hong Hai Environmental Art.

- For a lucid account of the bicentennial’s inherent contradictions as it began unfolding in 2019, see Nien Yuan Cheng, “The Singapore Bicentennial: It Was Never Going to Work,” New Mandala, March 6, 2019.

- In Singapore’s contemporary art history, we see other interrogations of the figure of Raffles predating the bicentennial, such as in Lee Wen’s Untitled (Raffles) (2000), Ho Tzu Nyen’s Utama: Every Name in History is I (2003), and Fyerool Darma’s The Most Mild Mannered Men (2016). For a far more meticulous overview, see Ng Yi-Sheng, “Raffles Restitution: Artistic Responses to Singapore's 1819 Colonisation,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 50, no. 4 (2019): 599–631. Critical responses specific to the bicentennial year include Fazleen Karlan’s #sgbyecentennial (2019), or the closed-door Faffles Must Rall town halls organised by Farhan Idris and Kin Chui, involving discussions with other cultural workers, activists, researchers, and writers. These town halls perhaps provided some inspiration for a fictional book club in the 2019 theatre production by Alfian Sa’at and Neo Hai Bin, Merdeka / 獨立 / சுதந்திரம்.

- Melody Zaccheus, “Revamped History Book Gives Voice to Orang Laut,” The Straits Times, May 25, 2019.

- Lily Zubaidah Rahim, Singapore in the Malay World: Building and Breaching Regional Bridges (London; New York: Routledge, 2009), 2.

- As quoted from Faris Joraimi in a Facebook post reviewing Raffles in Southeast Asia: Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman, dated February 10, 2019. Widely circulated Facebook posts by Alfian Sa’at, Faris Joraimi, Ng Yi-Sheng and Siew Min Sai would form some of the most salient critiques of the exhibition.

- Farish Noor, “Don’t Mention the Corpses: The Erasure of Violence in Colonial Writings on Southeast Asia,” Biblioasia, 15, 2 (2019).

- Achille Mbembe and Libby Meintjes, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 14.

- Syed Hussein Alatas, Thomas Stamford Raffles: Schemer or Reformer? (Singapore: NUS Press, 2020), 75.

- Jacqueline Elam and Chase Pielak, Corpse Encounters: An Aesthetics of Death (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2018).

- Tim Hannigan, Raffles and the British Invasion of Java (Singapore: Monsoon Books, 2012), 17. Hannigan further notes that “everyone in Indonesia, not to mention Britain, seemed to have forgotten [the British Interregnum]”, despite the period being of immense impact to Java.

- Faris Joraimi, “Still ‘Essential’? Roundtable on the icon of Stamford Raffles,” (roundtable, Singapore, June 27, 2020).

- Syed Hussein, Thomas Stamford Raffles, 25.