out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 Grace Samboh in conversation with Tamarra

out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 is a special series of creative, critical and personal responses by artists on the significance of the coronavirus to their respective contexts, written as the crisis plays out before us. #workfromhome and #stayathome have disproportionately impacted marginalised communities around the world. In this open letter, curator and researcher Grace Samboh shares her conversation with artist Tamarra about the pandemic’s impact on transgender communities in Indonesia.

Image courtesy of Grace Samboh.

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

#workfromhome and #stayathome have disproportionately impacted marginalised communities around the world. These widely used slogans drove curator and researcher Grace Samboh to learn more about how the pandemic has impacted transgender communities in Indonesia, through conversations with artist Tamarra. Tamarra’s work includes installations, soft-sculptures, videos and performance art amongst others. Grace works in Yogyakarta, Jakarta, Jatiwangi and Medan. Grace's curatorial work and groundwork research unravels how social realities, relationships and the past coalesce in various contemporary practices.

An open letter: How have you been?

An abridged conversation between Grace Samboh and Tamarra

Hello, dear friends! I sincerely hope that you are all safe and sound wherever you are. I guess I am considerably privileged as I can pretty much say that I am okay, I am good, I am safe and sound. Amidst the beautiful chaos all over the planet, I am privileged enough to say that this may be the moment that many of us artworkers keep saying that we lack: more time to think, more time to develop ideas, more time to research, more time to experiment, more time to exercise. In fact, the current worldwide pause on—particularly—arts and culture events fills me with hope. Maybe, we will soon experience a surge of more thoughtful works, more caring and sensible practices…

The recently-popular slogan, #workfromhome or #stayathome has really gotten to me. I guess that is why I have declined quite a number of invitations to speak about or discuss “what art can do” or “how are you” or “how to be productive from home” or “how to function in this new normal” and so on. I do not want to perceive this situation as the “new normal.” Nor do I want to be associated with ideas of normalcy. I would like to just be honest—this situation is not okay! And, since we will have to live with this for quite some time in the future, we need to find the courage to say that we’ll be living our lives as curious and as furious as we have been before, even if all the circumstances are different.

Even if I am safe and sound here in Yogyakarta (Jogja), it does not feel like home. I have been here in Jogja for the past five months. I am technically a registered citizen of Jogja. My house is here. My dogs are here. My library is here. If not for a year-long residency, my partner would have been here too, I guess, as this is also his working studio. Jogja is where we formally reside. But this town has not been the only locus of my work, his work, or our work. Since 2014, we have been trying to live in different places. It began with wanting to experiment with whether we, as artworkers, could function with different livelihoods, and in the different societies that we attach ourselves too. So, technically, we have been living a rather “mobile” life between Jogja, Jakarta, Jatiwangi, and Medan … All of which we can call home. All of which, I can call home.

In thinking about that slogan I think of Tamarra, a dear friend who was my housemate from 2014 to 2016. Tamarra is currently completing an undergraduate degree in history at the Sanata Dharma University, Jogja. Tamarra is an artist who makes installations, soft-sculptures, videos and performance art amongst others, and works individually as well as collaboratively. In 2017, Tamarra started a life-long project to research how transgender communities navigate their lives in the vast Indonesian archipelago. Tamarra began with a pilgrimage —as Tamarra calls it— to South Sulawesi, to meet the bissu community (bissu is recognised as the “fifth gender” in Bugis culture). In 2019, Tamarra’s curiosity led Tamarra to several parts of East Java where members of the transgender community are celebrities in the mobile folk arts scene. Back in Jogja, a place that Tamarra comfortably calls home, Tamarra started an experimental performance platform for the transgender community that Tamarra grew up with. Dubbed We Are Human, the platform has been holding performances and various kinds of collaborations with artists, art spaces, and local businesses since 2013. AMUBA, the “very first trans-girl band in Indonesia” according to Vice, was born from this project. Tamarra is an active member and promotor of the band.

We have been in close conversation about Tamarra’s solo show since the middle of last year. It was to be held in RUBANAH Underground Hub at the end of October 2020, but like so many other art events was halted by the pandemic. Instead of my rather dull #workfromhome #stayathome situation, I thought it would be more interesting to share my conversation with Tamarra, who is connected to a larger, more diverse community. How is Tamarra? Can Tamarra #workfromhome? Is it “productive” for Tamarra to #stayathome?

---

Grace: Tam, how have you been? #workfromhome #stayathome is good for your upcoming solo show, no?

Tamarra: Says you and your privilege! <laughs> During the pandemic, all the bad sides inside yourself come out. And, because you are locked indoors, there is almost no way other than to confront that bad side. Before the pandemic, I start working on a new artwork inspired from a ritual that the bissu community calls matinro. It is like “mati suri” in Bahasa. What is it in English? Something like coma, almost dead, torpor… But it is expected. Unlike in sickness, or disease, where it is a surprise. Bissu prepare to get into this mati suri or torpor; they say it takes them to another realm, another reality. In my logic, or what I learned from this, is how this ritual is about looking into oneself, looking into the inside of yourself, inside your body, inside the corporeal. Like a break from normal social life where your environment looks at you, defines you, demands that you be this and that.

I cannot show you the work just yet, but I can tell you a bit about it. It is an installation made out of used t-shirts. Mainly black. I cut and weave the t-shirts, or you could say I make ties and bondages with the t-shirts to create a soft sculpture of a vagina. A soft sculpture that will be the entrance of my exhibition. I want to offer the thought of going back into your mother’s womb. Before gender norms existed, before there were expectations of what you should be, before you had roles in society… Why do we go back to the mother’s womb? To think again about ourselves, our existing selves, its multiple sides. To free our minds from society’s demands and expectations. To have the courage to be ourselves. Anyway, it is a work in progress…

Grace: Now that your classes have moved online, you do have more time to spend with your craft, with your handiwork…

Tamarra: I’d still say, says you and your privilege! Now that everything is done from home, online, who’s paying my electricity bills? Who pays for my Internet bills? A day doesn’t pass where I’m not thinking about how my transgender friends are getting by! Can they afford their rent? How are they surviving? Do they have food for tomorrow? What about all the sanitation products that have become necessary because of the virus? With all the social restrictions, physical distancing regulations and travel bans, they basically have no jobs since most of them are either street performers or hospitality workers (waitresses, hair-dressers, customer service officers, etc). Even I, who earn my living by being a professional tour guide for a well-known travel agency in town, no longer have work. No work, yet all the bills are still coming… Room rent, electricity, water, and so on…

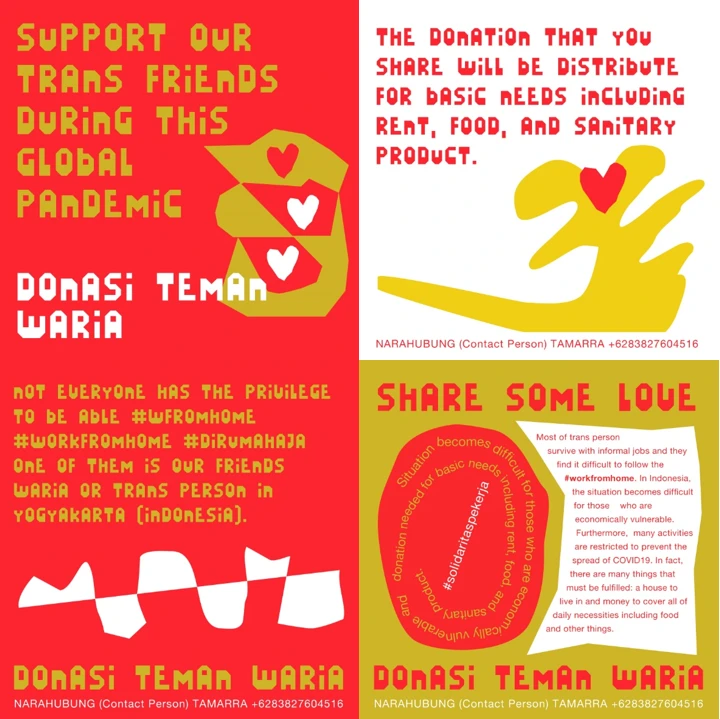

Grace: So, your school is not taking care of your Internet bill? Are they at least cutting down school fees? And what about the government’s social department? Aren’t they doing anything for the transgender community at large? Is that why you are starting an open call for donations?

Tamarra: Definitely! I was startled at first. I don’t really know if this is the right move. But I simply cannot not do anything. At the very least within my hometown, for my homies. The donations, as you can see in my Instagram feed, will be distributed for my homies’ rent as well as basic and sanitising needs. I list them by name, so anyone that donates knows that it is not a random or abstract recipient. There really is somebody, an actual person who is in real need, who will receive it. Monthly or as long as it’s needed…

Grace: Wait, wait. So how does this open call for donations work?

Tamarra: Nothing complicated. I post a poster on Instagram that asks for donations to the transgender community in Jogja via my bank account. I aim to cover basic necessities, rent and sanitation products for as many friends as I can with the money donated. So, once a week, I calculate how much money I have received and distribute it immediately. Since the community is close-knit, those whose needs must be prioritised are easily known. Some friends prefer to donate food supplies and sanitation equipment because they are involved in public kitchens or making do-it-yourself sanitation products. I gather these things and distribute them to my friends.

Grace: Aha! This process reminds me of the artwork you just mentioned [matinro]! I am sort of seeing it as a “hunting-gathering” method. Well, not so much of the hunting, but pretty much the gathering part. You gather your friends’ unused, second-hand shirts and use them to make a soft sculpture. I thought you were thinking about waste and recycling for ecological reasons, but I realise you help your friends in a similar way. Maybe it is rooted in the simple idea of sharing within a community or, to a certain extent, the redistribution of assets… I mean, your open call wasn’t aimed at institutions or some sort of a demand towards the government, right? You directed the call to your friends that may have a bit more of something—be it money, food, or whatever—to share with others in need…

Tamarra: <laughs> I can’t believe it! You found a connection! I’ve never thought of it in that way. It is of course not always as seamless a process as you make it out to be. A month ago, I forced myself to move to Jakarta to find a job. All of us simply need a minimum amount of money to survive, right? I had to move to Jakarta for a job with a stable salary due to the impossibility of finding any work opportunities in Jogja. I mean, I guess, I too am privileged to at least have this option; to move for work, even for a small sum of money. Many of my friends who work on the street, whether as buskers or selling things like newspapers or food, really have no solution for income with enforced physical distancing. So your anxiety towards #workfromhome #stayathome really does make sense. Not everyone can afford it…

Grace: I can’t even think of my artisan friends or art-handler friends. With all the postponement or even cancellation of exhibitions and events, how are they surviving? What can we do for them? Are you in touch with your bissu friends in South Sulawesi? How are they doing? Are social rituals also halted? What about the transgender performers that you have been making contact since last year? Mobile folk performances must all be halted too, no?

[Grace’s note: For context, since 2019, Tamarra has been travelling to and from Jombang and Mojokoert in East Java. Besides expanding Tamarra’s friendships and community, Tamarra has been interested in learning more about crossdressers, who are actors in ludruk, a type of traditional, local performing art. Folk art. People art. Ludruk operate in groups and are nomadic, performing from one village to the next.]

Tamarra: It is amazing to see how the folk art people have been living their lives! They have paddy fields and a hairdressing salon. At the same time! And they are also actors. In all these different roles, in their daily lives, they are like totally different people. The farmer, the hairstylist and the actor, who can basically be or play the role of anyone. These actors are transpeople, even if they may not be familiar with the term. I am very curious about the traditional crossdressing culture in the folk art scene. You would think that villagers are conservative. But if this form of art is more than a hundred years old, it means these practices have been part of the society for a very long time. At least way before Abrahamic religion was established… This folk art has survived all the changes that came with religion, battles and war….

For example, the case of sri panggung (female superstar). The popular actor Umi Salamaun has the hajj honorific, given to a person after their pilgrimage to Mecca. Of course for Umi, the journey was taken as a “normal man.” But, I argue that Umi Salamaun is a transwoman; that she prefers “she/her/hers” pronouns. Her story circulates as a representation of truth that others cannot confront directly. As Umi’s family cannot accept her as transgender, her neighbours also cannot accept it. So, at home, Umi dresses as man: a man who nonetheless owns a hair salon. When Umi performs, she puts on makeup, then a dress, and voila! Umi becomes a woman! All these roles that Umi plays gives form to her different selves that exist inside oneself.

Grace: I guess we need to learn from them! Especially how they live their lives, how they treat their bodies and their understanding of “self” and its social roles. Cosmopolitan people may say that they are “chameleon-like”, performing selected selves with their bodies and its attributes in different circumstances. But, I think, because the society in which these actors thrive don’t have that understanding of self-expression—and I don’t mean this in a condescending way—they are way more free than we would expect!

Tamarra: True! Umi Salamaun doesn’t only own a hair salon, she also has a rice paddy field that she attends to on her own. For her, and for many of transpeople in this folk art community, the earth is home. The planet is home…

Grace: This is a good place to end our conversation for now. The planet is home, indeed! I hope to see you soon, Tamarra! Come back to Jogja!

---

Despite the beautiful chaos around us now, dear friends, I sincerely hope that you are all well—wherever you are :-)

Jogja & Jatiwangi

August 2020

=g=