out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 Chu Hao Pei

Since 2017, Chu Hao Pei has been involved in different forms of food rescue in Singapore—from rescuing leftovers from buffets, to collecting edible food from dumpsters. Through the COVID-19 pandemic, he has witnessed problems of food distribution intensify and the issue of food waste worsen. In the thirteenth contribution to out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19, Hao Pei details the problem of food waste in Singapore and responses to it, both in practice and imagined.

Image courtesy of Chu Hao Pei.

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

Since 2017, Chu Hao Pei has been involved in different forms of food rescue—from rescuing leftovers from buffets, to collecting edible food from dumpsters. Through the COVID-19 pandemic, he has witnessed problems of food distribution intensify and the issue of food waste worsen; yet another glaring structural issue exposed by the pandemic. In the thirteenth contribution to out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19, Hao Pei details the issue of food waste in Singapore, the community-led responses that have sprung up to combat it, and creative examples that might inspire further action. Hao Pei is a visual artist who works primarily with installation and lens-based media in a practice that explores shifting physical, sociological, and emotional connections with our natural and urban landscapes. He is currently working on a mixed-media installation at The Substation.

Food rescue: From radical sustainability to addressing social needs

Chu Hao Pei

Food rescue—the process of retrieving and redistributing edible food that would otherwise go to waste—often requires one to go out of their comfort zone. It frequently involves collecting food from unexpected places, like the dumpster, or approaching food vendors for leftovers. Unlike other sustainability efforts, those involved in food rescue have to contend with the social stigma of asking for leftover food, or of consuming food that has been thrown away (but remains edible). Since 2017, I have been involved in different forms of food rescue. As a result, I have been pushed to venture into uncommon territory like trash compactors in shopping malls and back alleys of food stalls, and have mastered the art of avoiding surveillance, coordinating with allies on the ground, and turning up at events with buffets to rescue leftover or disposed food.

My experiences have given me a deeper understanding of the systematic flaws that lead to food waste, the communities that rely on rescued food, and the inherent anti-capitalism of sharing. Food rescue and distribution stands in direct contrast to the current modes of the market economy, as it does not require “the mutual give-and-take that forms the structure of exchange, both of economic exchange, as in a market, and of symbolic exchange, as in the giving and returning of gifts, words, or other symbols.”1 Rather, food rescue and distribution mirrors the practice of almsgiving, exposing excess and reconfiguring the constraints derived from the capitalistic structure of the economy, where one gets only what one pays for.

When DORSCON Orange was announced in Singapore in early February, most, if not all, food rescue efforts came to an abrupt halt despite objections from some food rescuers, who noted that food vendors were still allowed to operate. Technically, this increased food waste in the last part of the food chain system increases the amount of effort required to tackle food wastage. As a result, such efforts took on a more guerrilla approach. Some food rescuers began to self-organise, circumventing formal platforms to link up with vendors to continue food rescue operations. But safety concerns due to COVID-19 arose alongside new rules and regulations that restricted access to food, resulting in a significant decrease in food rescue efforts and an unprecedented increase in food waste.

The Circuit Breaker2 and closing of borders disrupted the food chain system, intensifying the problem of food waste which had also surfaced further up the supply chain. Later in June, it was reported that an egg distributor in Singapore had to dispose of 250,000 eggs: spill over from the height of the pandemic, when affected imports caused unstable supply.3 Before the pandemic, food rescue groups would have been informed of such surpluses, as many food suppliers are in contact with food rescuers. While it remains unclear why food rescue groups were not informed of this surplus, the situation’s mishandling reflects the importance of food rescue, particularly in a crisis like this.

As a food rescuer, I am distraught by the structural gaps I see in the system—the unprecedented surge in food waste from the supplier, contrasted with the shortage of food in the earlier phases of the pandemic. A food rescuer is often described as a “firefighter” plugging the gaps of food waste from systematic flaws, but despite our best intentions, our diminished role during this pandemic has made us unable to fulfil our goals. I have realised that while there is a strong desire on the part of food rescuers to reduce food waste (personal consumption or otherwise), the inertia of systematic bureaucracies is always stronger.

***

Some groups have been adversely affected by the limitations imposed by COVID-19 restrictions. Veggie Rescue @ Pasir Panjang, which falls under the umbrella of SG Food Rescue, has always seen a large turnout of volunteers. But these days, only individuals with access passes are allowed into Pasir Panjang Wholesale Centre. The number of rescuers has since been largely reduced. Instead, volunteers with vehicles are in demand as they can help transport rescued food for distribution. Likewise with smaller food rescues, vendors have stopped or reduced food rescues over safety concerns and measures preventing the spread of COVID-19.

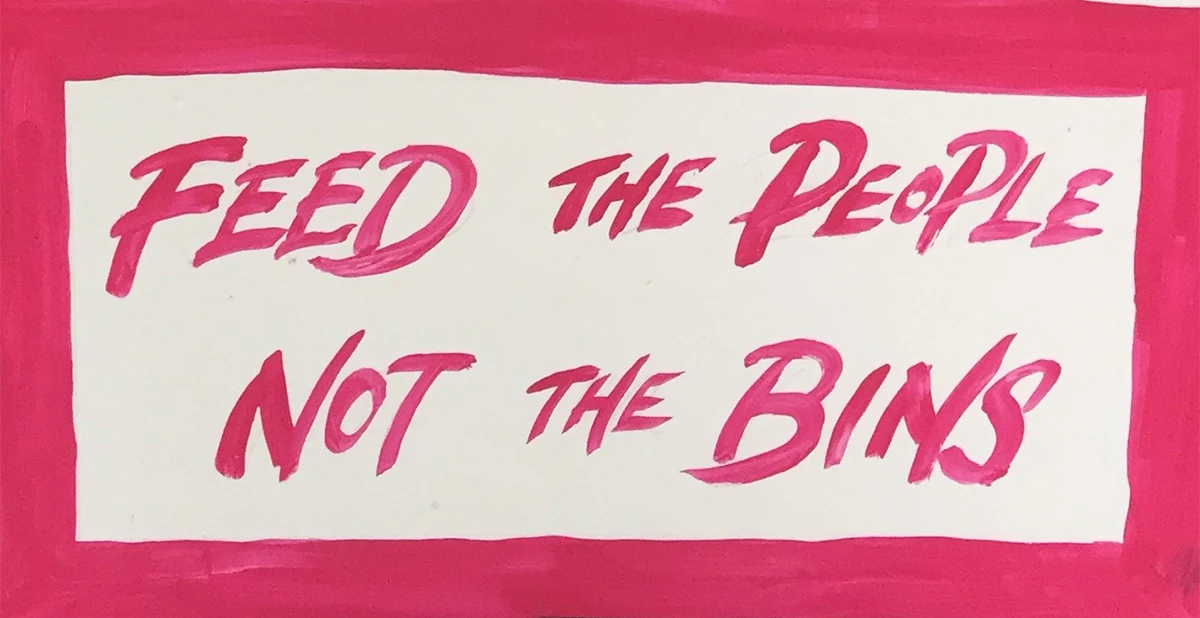

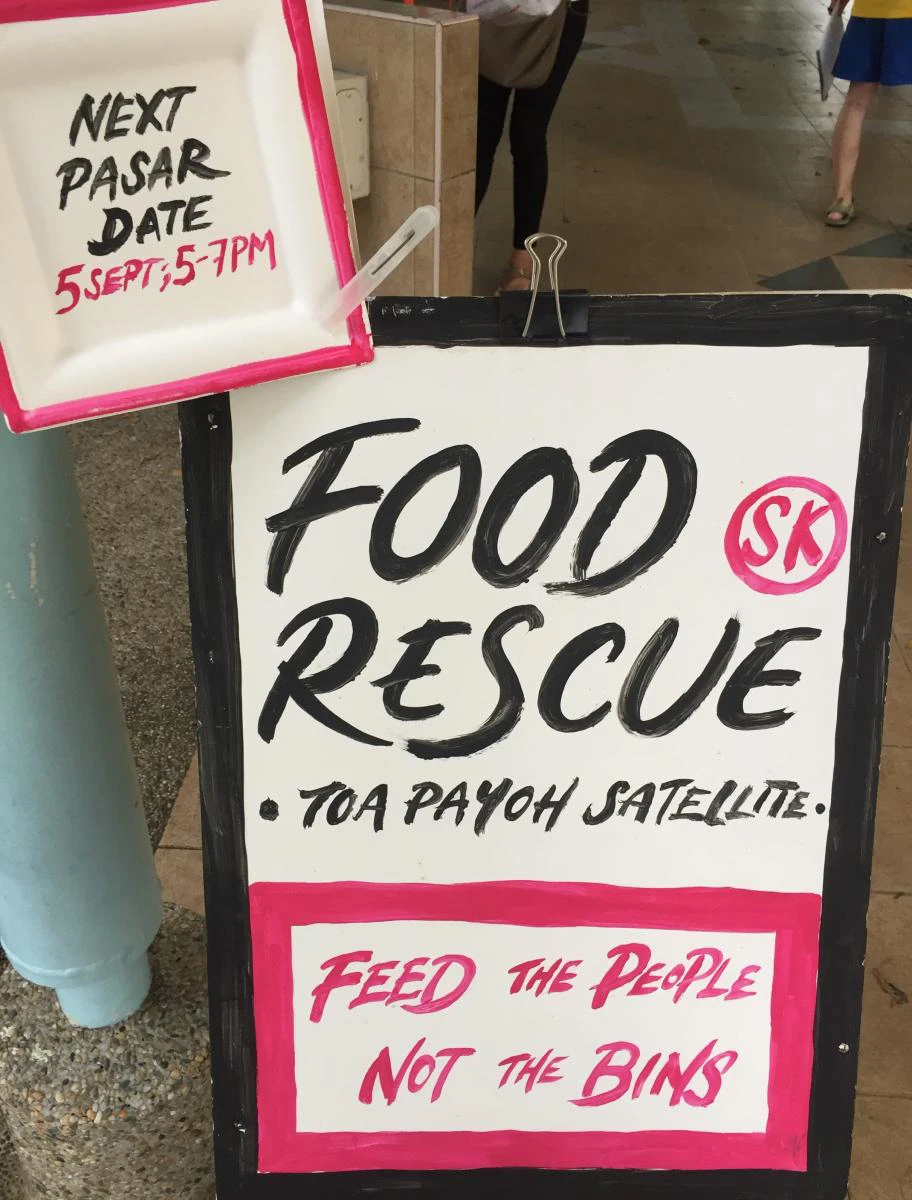

Despite the limitations and bureaucracy, others have found a way to adapt to the situation. Food Rescue Sengkang (FRSK) was formed in response to the “new normal.” Granted access to the premises and with an abundance of time in lockdown, the founders of FRSK and many first-time volunteers started the group to plug the food rescue gap. I witnessed first-hand how the distribution of rescued food took place under the “new normal” at FRSK’s latest satellite distribution point in Toa Payoh, to which I was invited to help. As before, priority was given to the elderly and individuals with physical disabilities. But new measures such as mandatory social distancing, temperature taking, entry of visitor logs, crowd control and the use of gloves were imposed. Extra procedures aside, everyone was cooperative and moved in an orderly fashion, once again proving rescuers’ adaptability and ability to work around restrictions.

Although all are welcome to rescued food, according to one regular FRSK volunteer, its new beneficiaries are the “sandwiched” middle class who face financial difficulties owing to the economic effects of the pandemic4. The rescued food has helped cushion these families’ daily expenses, allowing its healing to affect others too. At the same time, some food rescue groups remain dedicated to assisting the peripheral groups and now commit more food to needy and elderly communities.

It is great consolation to learn of helping and healing during such a perilous time for food rescue. But as food rescuers double down on their efforts, compensating for the financial shortcomings of the capitalistic structure of the economy by distributing food to the vulnerable and “new” vulnerable groups, we need to take a harder look at the social and economic consequences of this crisis. Could this also be a sign of a failing capitalistic structure in a time of crisis?

THE ACCURSED SHARE

Food rescue has shown that the sharing of resources is feasible, and that there is often not a shortage but a surplus of food in Singapore. Georges Bataille’s theory of consumption posits that all social and human processes produce waste, and it is this waste that is “the accursed share.”5 He proposes that the economy is fundamentally motivated by excess, instead of the scarcity that commonly defines our capitalistic systems today.

As my food rescue sojourns and the national statistics suggest, the increasing food waste highlights that Singapore, if not the world, does not need more food.6 Rather, it needs to plan the distribution of food optimally to correct the growing food waste issue, or in Bataille’s words, the accursed share. The same can be said for areas or communities where excess resources can be collectively shared.

Two examples demonstrate how the sharing movement can correct the imbalance caused by a resource-devouring capitalistic system, and offer up some possibilities for us when re-imagining what a systemic response could look like.

Independent cultural and social space Post-Museum’s Singapore Really Really Free Market (SRRFM), inspired by the counter-capitalist movement that originated in America, is a flea market where all items on site are free. It functions through the active participation of the community who give and/or take. The labour, or self-organisation, involved in SRRFM also comes from the sharing of time and effort by friends and volunteers. The multiple facets of SRRFM hinge entirely on the practice of sharing, which manifests through tangible forms as well as intangible means.

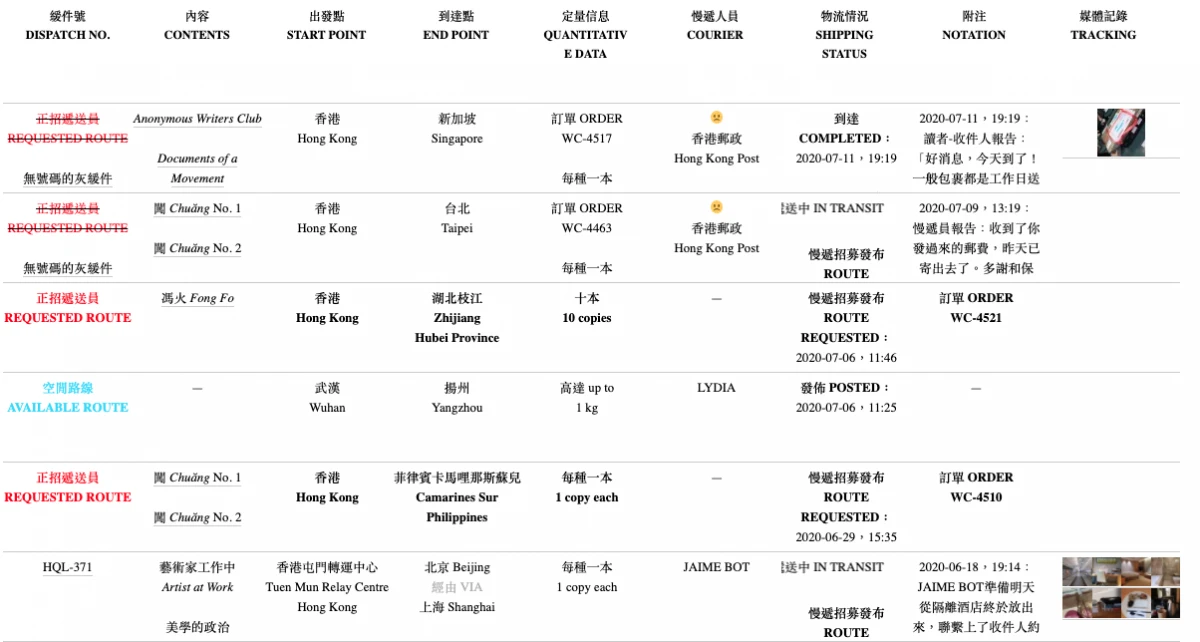

Display Distribute, a project which began in Hong Kong in 2013 as a documentary gesture of a distinct urban phenomenon, has unfolded as a series of investigations taking the form of interventions, research initiatives and exhibitions over the past three years. Through the contributions of various artists, writers and social practitioners, it has grown to form a unique document attesting to the ad-hoc arrangements that can emerge from a particular socio-economic environment.

Display Distribute’s LIGHT LOGISTICS epitomises this spirit. LIGHT LOGISTICS is a free person-to-person publication distribution network enabled by the surplus carrying power of couriers. One can volunteer to transport books to a designated location(s) if they are travelling there, so there is no intentional carbon footprint. In return, they receive a discount on books.

It is driven by the peer-to-peer sharing of itineraries within a specialised network; apart from having no restriction on the time frame, it is a concept similar to the distributor-collector networks of food rescue. Not only does LIGHT LOGISTICS eliminate the unnecessary carbon footprint in conventional courier services, it also plays a part in a wider discussion of globally-enabled and dismantled forms of exchange amidst a late-capitalist networked production.

With the COVID-19 situation stabilising in Singapore, we see the return of almost-full operation capacity alongside food rescuing activities, albeit with preventive measures in place. People who were not beneficiaries of rescued food before have now dispelled their misconceptions: a small step in shifting mindsets and more importantly, the need to share in the looming omni-presence of multiple crises — a pandemic and climate change.

Sharing has become more prevalent and perversely counter-intuitive to the capitalistic systems we live in. Beyond state welfare and mutual aid, it has helped reduce the financial effect of the pandemic on some, if not most beneficiaries. It also forces us to relook the excess, in this case, food, that our society continues to create, and how the mobilisation and distribution of resources allows us to assist communities in need while simultaneously reducing the growing problem of food waste. Most significantly, sharing through food rescue mends the failings of capitalism. While still a distance from influencing the structure of our economy today, the seeds of Bataille’s “accursed share” have been planted in the cracks of the society exposed by this pandemic.

What initially began as a personal effort of radical sustainability to reduce my own food waste has been transformed into a social act. Instead of being involved in food rescue solely as a participant, I am now an organiser recruiting collectors to sustain regular rescue efforts, and approaching food vendors to donate their leftovers. It has been equally, if not more satisfying, to see a community come together to share with others.

When the world came to a standstill, our planet recuperated. In this brief recovery, have we reflected on our capitalist-driven consumerist lifestyle, or did we continue relentlessly for the sake of convenience and economic development? While we take aim at governmental and corporate policies that fail to tackle the global issue of climate change, we as individuals need to, or must, inject radical values of sustainability into the mainstream to address the plight of the planet.

Notes

- Cornelia Sollfrank and Wolfgang Sützl, “Sharing – the Rise of a Concept,” A Peer-Reviewed Journal About (APRJA); Excessive Research 5(1): 2016, 83-87. https://doi.org/10.7146/aprja.v5i1.116043

- The 2020 Singapore circuit breaker measures, abbreviated to "CB," was a stay-at-home order and cordon sanitaire implemented as a preventive measure by the Government of Singapore in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the country on 7 April 2020.

- Julia Yeo, “Too many eggs in S'pore now due to oversupply from imports, 250,000 eggs thrown away,” Mothership.sg, June 17, 2020, https://mothership.sg/2020/06/oversupply-of-eggs/.

- Justin Ong, “More households in need of food aid, including younger couples and private property dwellers: Charities,” TODAY Online, September 19, 2019, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/more-households-need-food-aid-including-younger-couples-and-private-property-dwellers

- Georges Bataille, The Accursed Share Volume I: Consumption, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Zone Books, 1991), 23.

- Navene Elangovan, “Trash Talk: The battle of the food waste bulge — why you should throw away less food,” TODAY Online, September 10, 2019, https://www.todayonline.com/features/trash-talk-battle-food-waste-bulge-why-you-should-throw-away-less-food