Painted Shadows: Highlights from a Queer Perspective

Painted Shadows: A Queer Haunting of the National Gallery seemed like a conventional museum tour at the Gallery. But instead of guiding the audience through the prevailing narrative of the Gallery’s artworks, the 2016 mobile lecture-performance by Ng Yi-Sheng illuminated their lesser-known queer histories instead. Varsha Sivaram and Mina Choo share their highlights from Yi-Sheng's talk on the lecture-performance, held in a closed-door session for members of Kolektif.

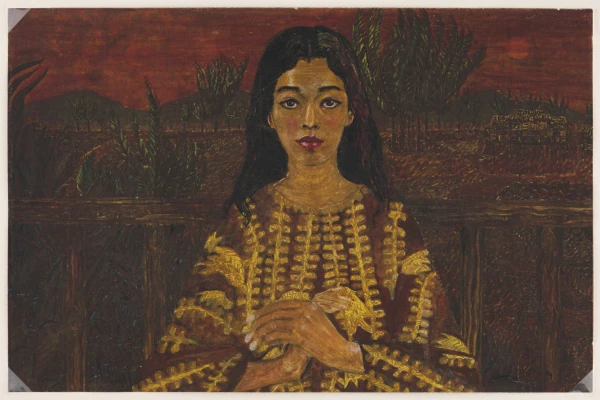

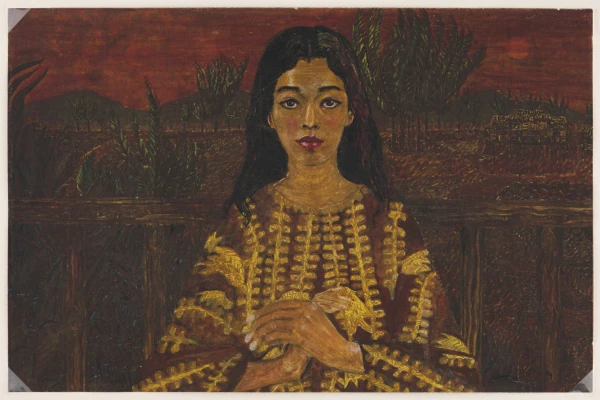

Self-Portrait, 1958

Oil on paper

49.3 x 75.3 cm

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Painted Shadows: A Queer Haunting of the National Gallery was a performance that took the form of a conventional museum tour at the Gallery. However instead of guiding the audience through the prevailing narrative of the Gallery’s artworks, it illuminated their lesser-known queer histories. Painted Shadows was originally conceived for The Substation in 2016 by Singaporean poet, playwright, fiction writer, journalist, researcher and activist Ng Yi-Sheng, and unofficially performed at the Gallery again in 2018.

Yi-Sheng spoke about his mobile lecture-performance in a talk titled disinheritage: stitching a history out of fragments to Kolektif, the Gallery’s flagship youth collective, in an inaugural closed-door programme commemorating Pride Month. Kolektif aims to bridge the arts, subcultures and the concerns of contemporary youth by empowering young people to reimagine the museum experience. Yi-Sheng elaborated on his performance by highlighting four of the featured works: Self Portrait with Friends by Patrick Ng Kah Onn, Exotic 101 by Michael Shaowanasai, Royal Family by Saya Chone and Cloud Canyons No. 24 by David Medalla.

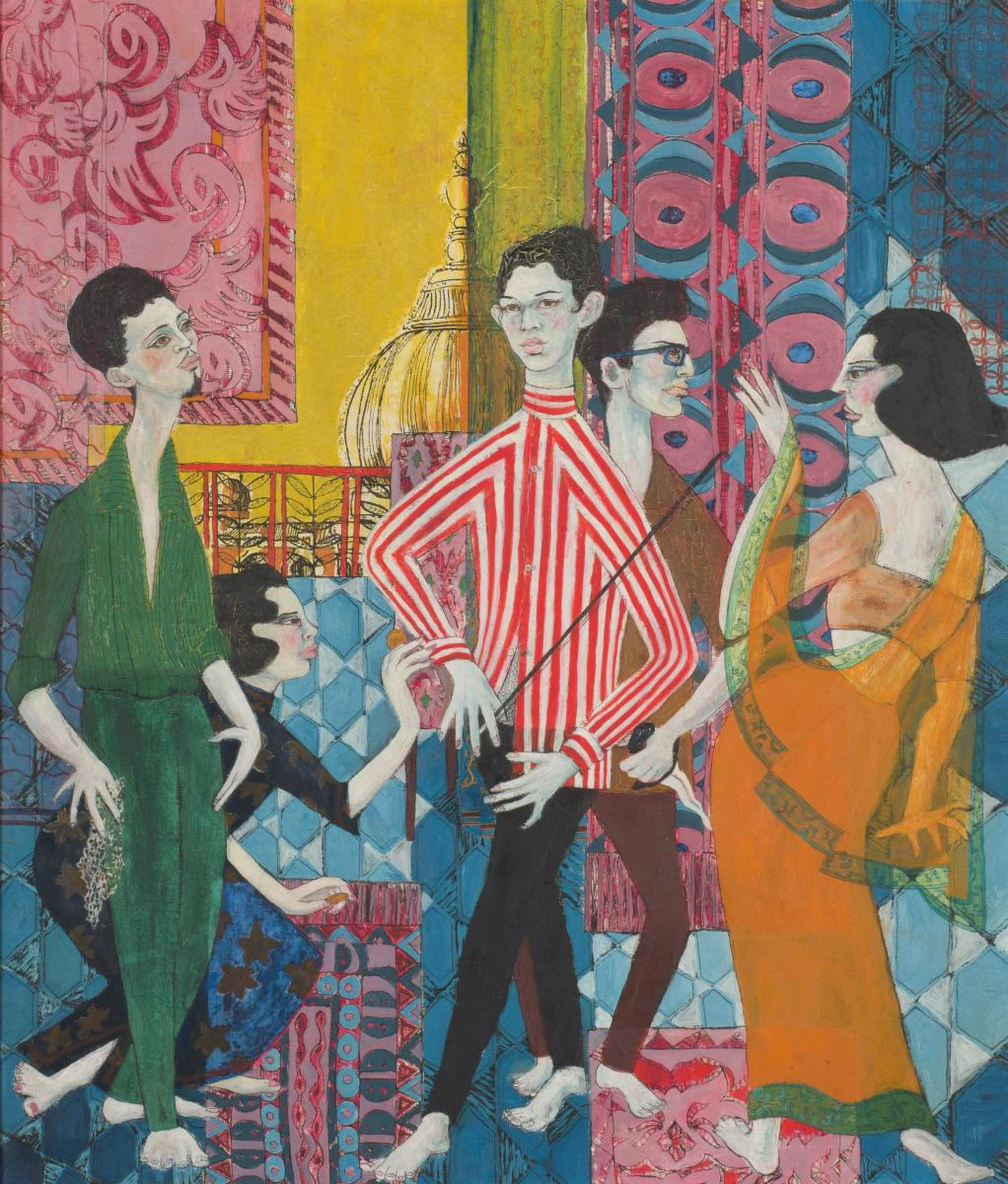

In Patrick Ng Kah Onn’s Self Portrait with Friends, five figures are silhouetted by bright, decorative batik-like drapes. Behind them, peeking through the window, is the dome of Jamek Mosque in Kuala Lumpur, the first mosque of its size constructed in the city. Ng and his friends’ movements are uncanny; their arms and legs curve at odd angles, as if marionette strings are pulling their bodies into dance. One is even crouched, as though in the middle of a performance. They wear mostly bright, fashionable clothes, enhancing the vibrancy of the scene. Yet it is an intimate one, as the circle of friends appear absorbed in their surroundings and each other.

As Yi-Sheng and scholars such as Simon Soon have discussed, Ng’s evocation of batik in his work was part of a wider fascination with Malay culture. In another work similarly titled Self-Portrait, the only person in frame appears to be a Malay woman. The title connotes that Ng sees himself as this Malay woman, troubling notions of race and gender, and calling on the viewer to question the presumed fixity of such identity markers. Yi-Sheng also speculated that Ng’s Di Tepi Sungai (By the River) may include Ng embracing someone who could be Dzulkilfi Buyong, an artist whose works also hang in the Gallery. The depiction of queerness and of potential connections between artists of the era broaden the narratives of Ng’s art for further development.

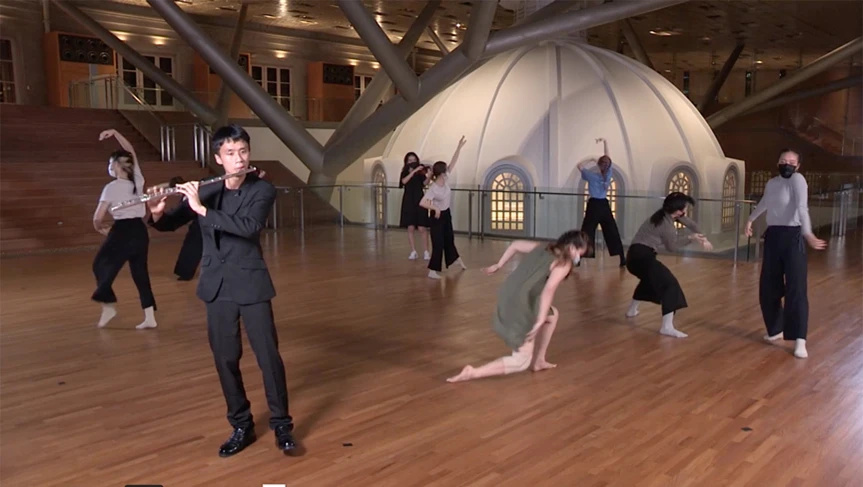

On approaching Exotic 101, the sight of a pole atop a small stage with an old-fashioned TV in front of it first strikes you. Then, you notice the audio-visual video on the television proclaiming: “Eurocentric language should not be your first language,” but if that is not the case, the pole can make you “instantly exotic.” As the performer in the video begins to dance on the pole, you realise that you’re meant to follow, and in the process, exoticise yourself.

Yi-Sheng recounted how he would, as the piece instructed, get up on the pole and follow along with the video on his tour, and how this would elicit surprise from the tour’s audience. As Yi-Sheng enacted and re-enacted Shaowanasai’s work, he seemed to create a parallel performance, while at the same time challenging the notion that museum art is untouchable.

The work interrogates what it means for a queer, Southeast Asian subject to leverage the white gaze for financial gain. However, the work itself sits within the Gallery’s colonial architecture. When a work that pushes back against the imposition of power is displayed in a building that once represented the same power as the former Supreme Court, how does it affect the way we see it? How does our engagement with Exotic 101 change when we remember that queer artists and performers would once likely have been held in cells the floor below?

Royal Family is one among Saya Chone’s many portraits of royalty, courtiers and aristocrats. Chone was one of the last Burmese court painters. He depicted monarchs of the region in his distinct style, imbued with techniques he learned in France.

In discussing the work, Yi-Sheng pointed out how the faces of each family member are near-identical; their only distinguishing feature being the mustache of the figure on the far right. Otherwise, Chone does little else to distinguish their gender identities, raising the idea of androgyny as a Southeast Asian aesthetic of beauty at the time.

One can find many representations of the human form carved on the walls of ancient Hindu temples or statues in Cambodia. Much like the figures in Royal Family, their genders were not immediately apparent–one would need to look at a figure’s chest, adornments, or the tools they carried. The absence of gendered depictions may have in fact been due to standards of beauty specific to the time. With Yi-Sheng’s revelation came reflections on current standards of beauty: could established, gendered ideals of beauty have less to do with “traditional” Southeast Asian culture, and more to do with colonial influence?

David Medalla is a Filipino artist known for his simple but experimental work. One such work is Cloud Canyons No. 24, a kinetic sculpture assembled from everyday objects. Foam, generated by a pump mixing detergent and water, overflows from the top of four Perspex tubes. The foam is then collected at the base of the installation. Medalla has described the work as being inspired by various experiences, as well as a Philippine dessert made with coconut milk called guinataan that bubbles as it cooks.

Yi-Sheng suggests that the common understanding of Medalla’s work sidesteps the most visually-apparent one: the shape of the Perspex tubes are rather phallic, while spirals of white foam ooze slowly down them. He placed this in conversation with Medalla’s A Stitch in Time, a work displayed at the Gallery in 2018. Medalla’s explanation from the Gallery’s website describes it as being “inspired by Medalla’s serendipitous encounter with a handkerchief at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, many years after he had given it away to an ex-lover at Heathrow Airport in London.” While emphasis is placed on the fortuity of the encounter, Medalla had discussed having two lovers at the time, neither of whom are identified. Perhaps the work might have benefited from an understanding of the artist's sexuality and his relationship to intimacy, and how this might have influenced his practice. That such possible readings are not widely disseminated reminds us of the context of Singapore, where lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) lives still largely remain unacknowledged. His personal history is so entangled with these works, yet these narratives remain hidden, disclosed discreetly only as “alternate” realities.

So, what about the future of queer perspectives? Gallery curators Adele Tan, Roger Nelson, Joleen Loh and Goh Sze Ying were also present at Yi-Sheng’s talk and responded to questions from members of Kolektif. Sze Ying and Adele discussed how doing the work of LGBTQ artists justice involves not just having them in the museum, but queering processes like curation itself. Informing future practices at museums–from the writing of labels that sit beside artworks to questions of funding–with this in mind can address the current gaps. As Joleen put it, plugging the gaps in representation is just the first step; addressing the conditions that have led to such gaps is the next. Perhaps we might then begin to imagine a queer future.