out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19

Simon Soon

out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 is a special series of creative, critical and personal responses by artists on the significance of the coronavirus to their respective contexts, written as the crisis plays out before us. Simon Soon reflects on how the lockdown in Malaysia gave him the opportunity to be reacquainted with a project that he started almost a decade ago, and the city he now lives in.

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

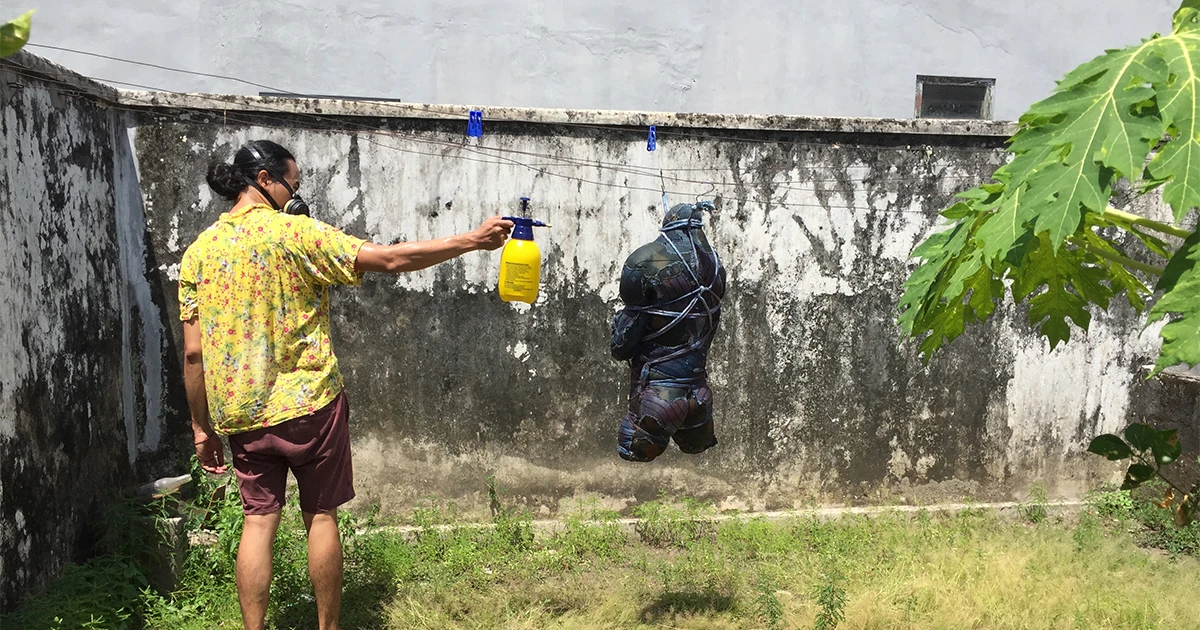

Lockdown in Malaysia has given Simon Soon the opportunity to be reacquainted with a project that he started almost a decade ago, and to consider the support systems that supports creative life in Kuala Lumpur. Simon is Senior Lecturer in art history at the Cultural Centre, University of Malaya. He has written on various topics related to 20th-century art across Asia and curates exhibitions, most recently Bayangnya Itu Timbul Tenggelam: Photographic Cultures in Malaysia. He is also an editorial member of Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, and a team member of the Malaysia Design Archive. He is also occasionally an artist, working chiefly through collaboration to explore cultural histories of the Malay archipelago.

Revisiting a Digital Map of Modern and Contemporary Art in Kuala Lumpur (1950-2010)

By Simon Soon

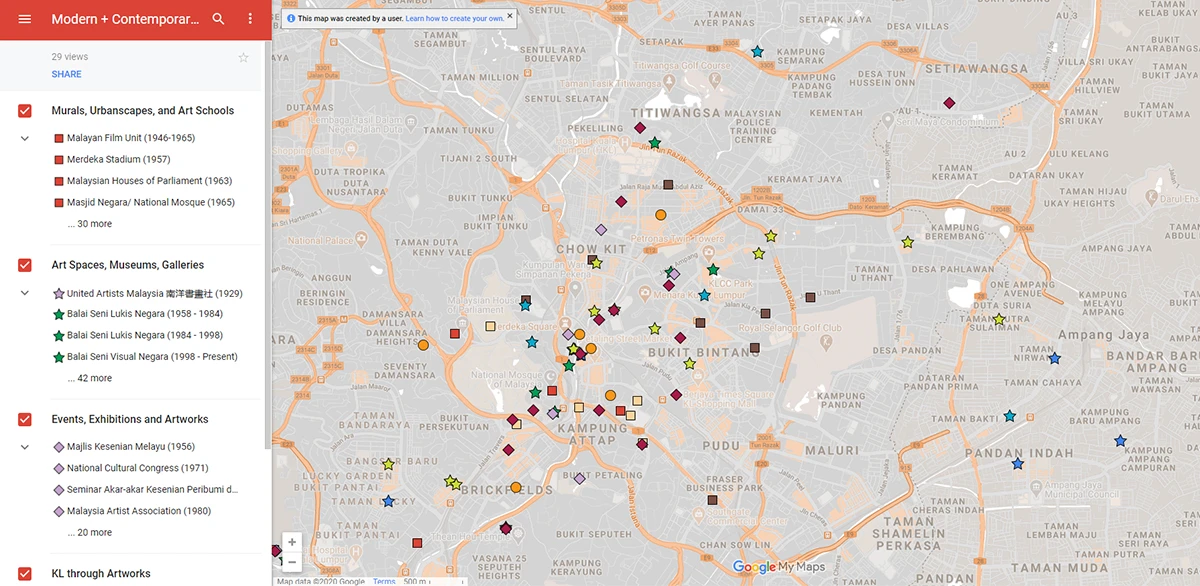

During the first nation-wide total lockdown in Malaysia that lasted from March to April this year, my not-so-successful attempt at spring cleaning led me to a realisation—accumulation in the 21st century isn’t always about tangible possessions. Amongst the things that I discovered lying around was a mapping project, Modern + Contemporary Art in Kuala Lumpur 1950–2010, that I had undertaken in 2011 while away in Sydney for my postgraduate studies.

Thinking back, I realise that I never had an outcome in mind for the project. While Google My Maps was released as early as 2007, it only came to my attention in 2011, by which time the interface had been gradually improved. I primarily found it useful as a type of sketchpad, since My Maps was convenient enough for me to simply locate events and connect ideas to a geographical site. Like all maps, the process of planting coordinates, zooming in and out to marvel at possible abstract connections that might appear before one’s eyes, across time and space, had an enduring appeal. Initially, I had no intention of sharing them with anyone. In my mind, for the longest time, they were sketchbooks at best.

I gradually abandoned many feverish ideas of what could be mapped. However during my spring cleaning earlier this year, Modern + Contemporary Art in Kuala Lumpur 1950–2010 emerged as something that I could possibly update. Ten years have passed since I worked on the project, but with time I too have gained a better understanding of the stories that make up the map. I have by now returned to a Kuala Lumpur that has a more visibly creative pulse—that is at least until COVID-19 turned the world upside down.

In a way, the map offered me a retreat back into the past. In part, I was seeking solace in a much more familiar and promising world. At the same time, I imagine this was also driven by a misplaced hope that I might be able to find answers in the history of creative life in this city. All we need to do is to learn how to remember.

Cultural life before the lockdown lacked neither flavour nor variety. But in a city like KL, made up of denizens from all over the country and beyond, memory of the city often doesn’t go very far back. Moreover, KL is a relatively young city, and I’ve always suspected that people come to KL to forget things and to escape from the wearisome burden of their past.

To make a name for yourself, it is easier to buy into the modernist myth. Namely, that acts of creativity emerge from a tabula rasa. Creativity has moreover been repurposed for capitalist economic discourse that privileges abstract values such as originality and authenticity.

Over the course of the lockdown, I found surprising comfort in the words of art historian Rosalind Krauss who relates in her book Under Blue Cup her experience of undergoing mnemonic therapy after suffering an aneurysm. Connecting her personal recovery to the manner in which avant-garde artists strategically harness creative rules of the past to create a bearing for themselves in a seemingly all permissive field, Krauss suggests’"If you can remember who you are (never a certainty when you are in comatose), you have the necessary associative scaffold to teach yourself to remember anything.”

When I reflect on why this particular map remains meaningful to me, I realise that I like that it was an attempt to give visibility to the associative scaffold that supported creative life in the city. Importantly, it recognises that these support systems have been laid down by successive generations. After all, these institutions and spaces undergird the very possibility and limitations of artistic culture in Kuala Lumpur. The map is—in hindsight—utopian. I have created an ideal and painted a city’s modern history as a celebration of its artistic creativity.

When I was invited by Perspectives magazine to write something, I felt it was time to update the map. In giving this map of modern and contemporary art in Kuala Lumpur a new life with a wider public reach than it had when it first took shape ten years ago, I hope that I can conjure another profile for KL—as a city sustained by energies. The map that I have created is by all accounts conventionally cartographic.

I have to confess that I have never been inclined to explore highly metaphorical forms of mapping, since the map is a means to an end. I wanted to remember the generous artistic ecology of a place that has bridged cultures and people, lest we forget, rather than concede defeat to the social frameworks that can only see the divisions and fragments along racial, class and language fault lines. This is not to deny that these fault lines exist—rather it is to recognise that when abstracted on a map in pattern and form, these markers of events and places appear like stars in the night sky.

There’s a belief that if we were to follow the stars, they might guide us safely back home. As I write this, most parts of Malaysia have entered into a second lockdown following the spike in COVID-19 infections. While this lockdown is less severe than the first, lethargy has cast its unsettling shadow as we wait for the year to draw to a close. We are currently vacillating between the uncertainty of the present lived reality, the political intrigues that continue to roar on above our heads in the news media, and what to make of the oversold promise of better days ahead.

2020 went by not with a bang but with a whimper. My generation grew up under the clarion call of then fourth Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad’s Wawasan 2020 (or Vision 2020). Announced in 1991, it was a developmentalist promise that set 2020 as a goalpost for when the country would fulfil its national destiny for greatness. With everything that has happened this year, one cannot help but experience the bittersweet aftertaste of a futurist vision that came to pass as the world fed on a capitalist vision of modernity—now that this vision has come to a grinding halt, we are limping back into various forms of half-life.

As we do so, I hope that we will be able to teach ourselves how to remember institutions, events and buildings that are sometimes hidden from view by the towering skyline that has blinkered our horizon. By remembering, we might be able to find a home in the world, and maybe even realise that greatness, in another form and sustained by another type of ideal, was really here all along. Perhaps, to rebuild the world in which modern and contemporary art matters, we might need to secure the blessings of ancestors.

——

Over time, my pool of half completed maps grew in size as I returned intermittently to my method without purpose. It is only of late that I’ve gained the confidence to share two of my recent Google My Maps databases. The first concerns the mapping of the Muharram celebrations in Penang and its transformation during the late 19th century into Boria performances (bit.ly/kolikallen). During the lockdown, my most productive hours were spent wandering like a flaneur in small towns across Malaysia with the help of Google Street View. This contributed to a My Maps database that I created of photo studios in Malaysia and Singapore (bit.ly/myphotostudios), and the exhibition Bayangnya Itu Timbul Tenggelam: Photographic Cultures in Malaysia.

My digital map is certainly not the first attempt. Later I learned of Yap Saubin’s more extensive mapping of contemporary art spaces of KL from 1990s as an artistic project. Beginning in 2005 as an art project, the data was also later housed on Google My Maps: http://mappingklartspace.blogspot.com

For a directory of contemporary art spaces and collectives in Kuala Lumpur, visit CENDANA.