out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 Marcus Yee

out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 is a special series of creative, critical and personal responses by artists on the significance of the coronavirus to their respective contexts, written as the crisis plays out before us. Collaborative project soft/WALL/studs constructed a weed garden for their programme Beyond Repair, part of the initiative Proposals for Novel Ways of Being. In tending to these plants, artist Marcus Yee unearthed a cascade of issues that affect us all.

Image courtesy of Marcus Yee.

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unique tensions, fears and doubts about the future have arisen. out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19 brings together artists' creative, critical and personal responses on the significance of the pandemic to their respective localities and contexts—what kinds of inequalities and injustices have the crisis laid bare, and what changes does the world need? If the origin of the virus is bound in an ecological web, what forms of climate action and mutual aid are necessary, now more than ever? Written as the crisis plays out before us, the series aims to spark conversation about how we might move forward from here.

Collaborative project soft/WALL/studs constructed a weed garden for the programme Beyond Repair, part of Proposals for Novel Ways of Being initiated by National Gallery Singapore and Singapore Art Museum. In tending to the needs of these plants, artist Marcus Yee discovered a microcosm of concerns, amplified through exposure by the numerous crises afflicting the world today. Guided by the nature of noticing, in this time, what does it mean to attend to ourselves, to one another?

Marcus Yee is an art worker from Singapore, currently pursuing studies in History and Earth Systems Science in Hong Kong. Since 2017, he has been part of soft/WALL/studs, a collaborative project involving several artists, writers, film makers, art workers, and researchers. Its projects include libraries, acts of amplification, hosting, exhibitions, fugitivity, counter-rhythm generation, support, resource gathering, research, writing, detournement, game-making, teaching, collaboration, and maintenance.

Words into Compost: Pullulations against cascades of crises

Marcus Yee

Attentiveness

Once you notice a bodhi fig, you begin to notice them everywhere.

They sprout through cracks in the pavement, creep along the edges of a longkang, grow into trees that straddle fences.1 I first identified the bodhi fig while cultivating soft/WALL/studs’ soil-raised weed garden.2 You first notice its distinctive leaves, overturned hearts accessorised with drip tips to match. Better known for being leafy shelter in Buddha’s attainment of enlightenment, the bodhi fig—a weed—is a curious vegetal crossing between the sacred and profane. Its Latin name ficus religiosia recalls a different intersection, this time, between scientific and spiritual.

In honing my attentiveness through gardening, I notice the world-within-worlds in the suspension of banality, alongside the beings that perform these effortless crossings between worlds. It was only while building soil beds, that I realise soft/WALL/studs already had a miniature grove of wildflowers in the building’s balcony-turned-storage. It’s the slender Benjamin fig that wrangles through a crack in a wall, the thyme-leaf spurges and coatbuttons that embank themselves along the aged building’s storm drain. Along this pocket river, the bodhi fig radiates.

By tending and extending this grove, I was pulled along this cascade of attendant relations: microclimates of precipitation and sunlight, soil underworlds, architectural gradients, human and more-than-human temporalities, shifting assemblages of insects, birds, fungi, microbes, and other plant matter.3

As seedlings began to take root on our soil beds, identification invited an open-ended gathering of speculation among co-conspirators, guests, and friends. Leaves were sniffed on, we picked up the fragrance notes of the Indian borage. Other times, leaf-ends were plucked and offered to another as an introduction. Nibble on this. Identification begins when faces contort from the overwhelming bitterness of the King of Bitters.

While identification risks becoming caught up in taxonomy, writer and editor Akiko Busch advises that “identifying something correctly may be the first step in knowing its larger place in life.”4 The state of "attentiveness" is an etymological offshoot of "attend," both from the Latin attendere (ad ‘to, toward’ + tendere ‘stretch’). To identify is to pay attention, to stretch one’s bodily boundaries, previously assumed to be discrete, only to find them porous in the process of finding relations.5

When the co-conspirators behind the garden conducted our regular Monday “weed walks” around Geylang, we found our bodies folded onto themselves, bending to closely observe wildflowers under the MRT tracks, letting their trichomes brush against our skin. Identification emerged as a practice of speculation over certainty.6 In attempting to sense botanical sensoria, we found our own sensorium stretched, undone, attended to.7

Attendant

The minor story of soft/WALL/studs’ garden took place within larger stories of ongoing crises. The cascade of crises—COVID-19, the climate crisis, the Sixth Extinction, racism, poverty, political stalemates—have focused attentions towards the oft-fragile connections between the ecological, epidemiological, economic, socio-cultural, and (geo-)political. While attending to more-than-human relations nearby, what figured as “attendant” became fuzzy, considered against a backdrop of the interlocking scales of global, national, and communal. “At-tending” is stretching, such that small stories become legible within global ones—or rather, larger stories become, in themselves, granularities.8

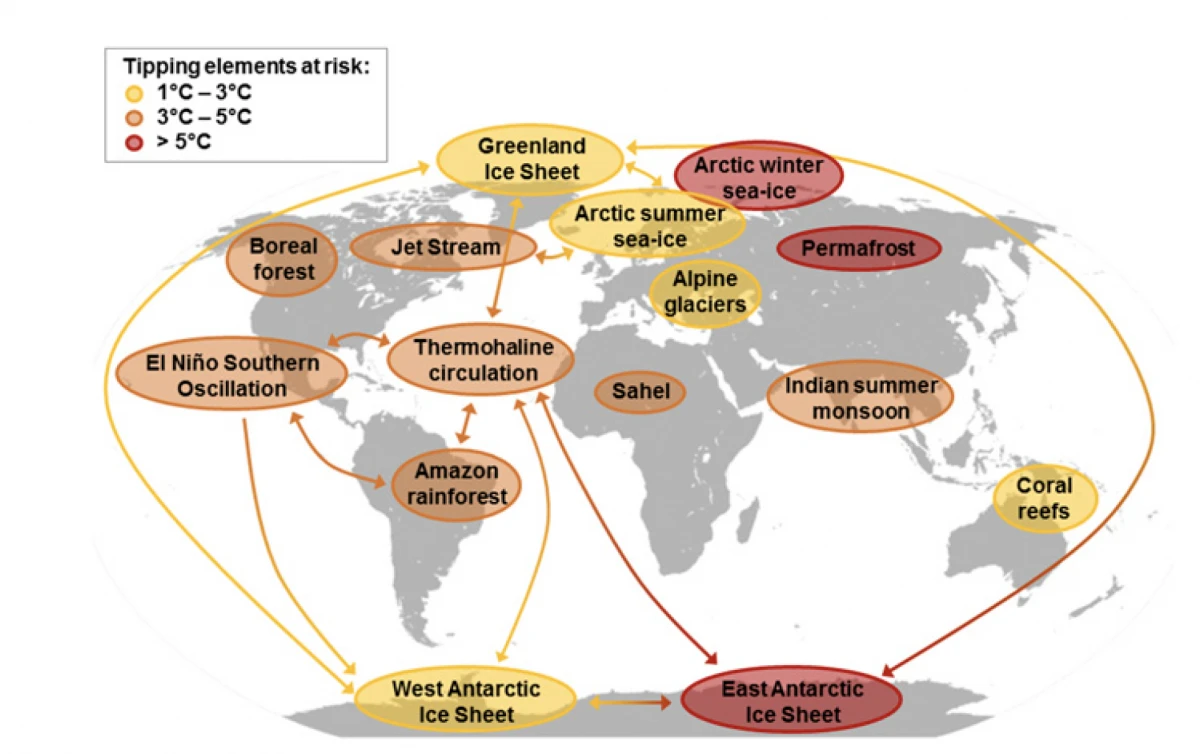

As writer Arundhati Roy observes, COVID-19 is far from a social leveler but an X-ray of pre-existing social fractures.9 Under the strain of a pandemic, structural inequalities within public health, food security, social welfare systems, the deep-seated fragilities of capitalistic institutions and geopolitical brinkmanship became glaring. These tipping cascades—to use a climatological term to describe the domino-effect of tipping points crossed by rising temperatures—do not end with COVID-19.10 Even as the pandemic ravages on, an economic recession becomes amplified, alongside a mental health crisis, ever-shifting political battlegrounds, a climate crisis that takes the form of intensified wildfires, desert locust infestations, flash floods, and more.11

COVID-19 marks the third time a zoonotic coronavirus has crossed the species barrier in three decades, raising alarms over the decline of biodiversity and loss of habitat under the penumbra of the Sixth Extinction.12 Extending Roy’s observation, colonial extractivism over non-human ecologies are part of these social fractures. In the nonlinear dynamics of tipping cascades, cause and effect are blurred: despite the admonitory aspect of ecological spillovers, pandemic recovery plans by national governments have instead meant regulatory relief and financial bailouts for polluting industries, including mining and fossil fuel interests.13

Singapore is not immune to this. The 17-member Emerging Stronger Taskforce, meant “to provide recommendations to the Future Economy Council (FEC) on post-COVID-19 Economy,” saw key representation by fossil fuel and oil commodity trading interests.14 This seems contrary to Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s 2019 speech on how “climate change defenses”—like the Singapore Armed Forces—are “existential for Singapore.”15 A seawall now looks like a Band-Aid solution against the incoming deluge.

As the pandemic unfolded, so did the farce behind the meme, “nature is healing, humans are the virus.” Nature did not heal.15 The meme’s ecofascist misanthropy not only glances over the affluent’s disproportionate share of responsibility; with sleight of hand, it makes culprits of populations already made vulnerable by environmental racism, poverty, and lack of access to critical infrastructure.16 “Humans are the virus” stems from a colonial imagination of nature that cannot envision collaborative lifeways with non-humans, especially after the fact of dispossessing indigenous people from their lands, outlawing their practices, and deriding their knowledges.17 In Singapore, popular appreciation over streetscapes of overgrown wildflowers and grasses ironically marked an inattention towards a labour ecology of low-wage migrant workers, of whom some are employed as gardeners, now under strict quarantine due to outbreaks in cramped worker dormitories.18

As opposed to paranoid overattentiveness—drawing connections that are not there—misanthropy shores up as anthropocentric inattention, an unwillingness to make connections beyond the ruins of bounded, normative categories. Distorted more-than-human relations mirror inattentions towards other humans and their sufferings.

Attending

How then, does soft/WALL/studs’ garden attend to these cascades of crises?

If “attending” means “solution-finding,” then perhaps, the garden does nothing.

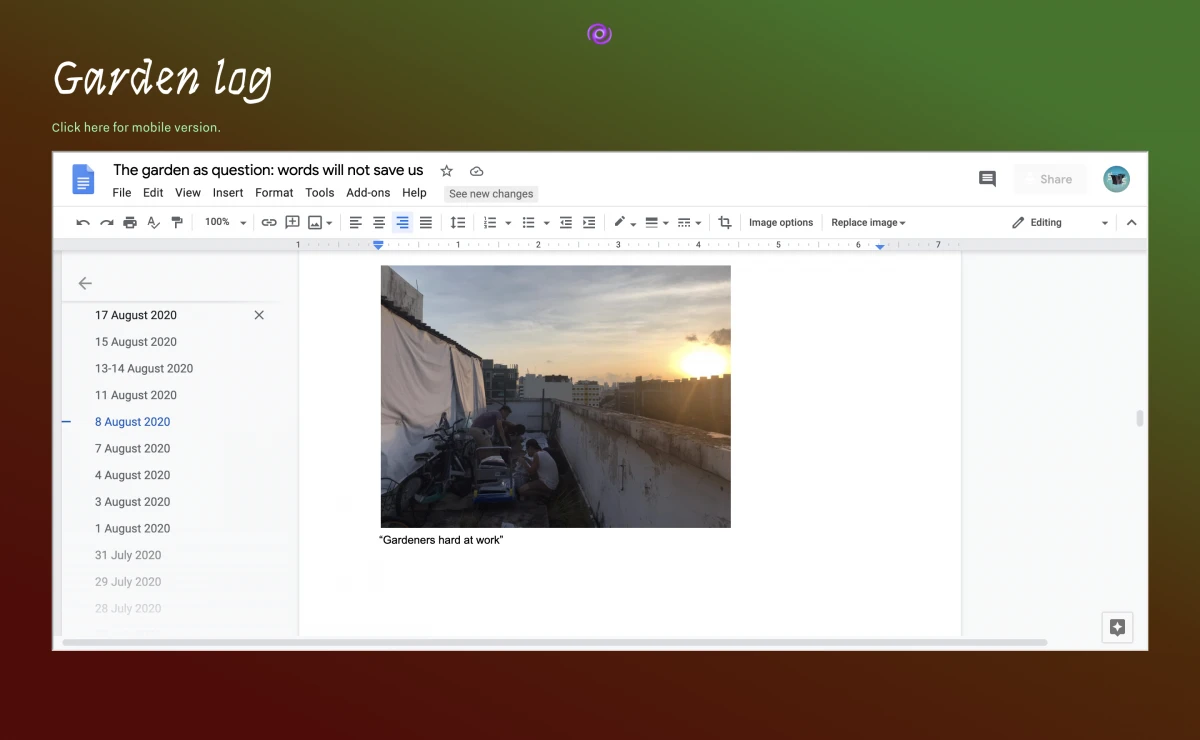

The garden’s name takes on a self-conscious verbosity while throwing a hint of shade: The Garden as Question: words will not save us. It is a refusal of the salvific and survivalist, a refusal stemming from a hyperawareness of the culture industry’s Janus-faced complicity in oppressive structural arrangements, while transacting in promissory rhetoric. Words will not save us.

Beyond mere presence, as in attendance, attending is a response-ability to the needs of others. In some cases, attending means knowing when not to show up, wording a gentle refusal, letting plants grow, tending to death.

We learnt this while attempting to transplant sidewalk weeds to our new soil beds. Within a few days, many of the transplants unleashed a repertoire of refusal; they browned, wilted, and dried up. A friend postulated that our loamy gardening soil was too nutrient-rich for weeds, used to clayey soils. Another mentioned that weeds thrived on neglect. What we perceived as dutiful care disrupted their hardy adaptations.

Reflecting on our choreography of transplantation, I realised that whereas much attention was placed on the plant itself, less attentiveness was offered to the plant’s shifting, attendant lifeways. A spleenwort that thrived in a shady habitat under a highway would not do well with all-day rooftop sunlight. Attentiveness articulates these assemblages, a refusal to see beings as discrete and insulated, as specimens without connection.20

Tending

“Attending” finds another etymological rhizome in “tending,” both in the sense of “care and cultivation” (as in tending to a garden) and in the sense of “inclination” (as in to tend towards).21 In The Garden as Question, tending intertwines care with refusal. These are refusals against salvific rhetoric, technoscientific productivism, the colonial alienation from entanglement. But refusal is not just a “no.”22 Refusals can be redirections. They play within generative limits and incommensurabilities, going beyond modes of conquest. These are the lessons of weeds, practitioners of refusal par excellence.

Amid the ongoing crises, a wellspring of practices and conceptualisations surrounding care has emerged.23 Yet, more than a “separate ‘cozy’ realm where ‘nice’ relations can thrive,” care is a political, messy, and non-innocent category.24 As scholar Maria Puig de la Bellacasa reminds us, what is done in the name of “care” could turn into a moralistic regime of control when some forms of care are prioritised at the expense of others.25

Image courtesy of soft/WALL/studs. Photograph by Michelle Lai.

In Singapore, the trimming, fogging, manicuring, reclaiming, and zoning of its landscape by the state are forms of tendentious care. Architects Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing call this “paramilitary gardening,” where gardening emerges not only as an ecological metaphor for the island-state’s political culture, it is also weaponised as technology “against civil unrest.”26 Indeed, a look into the environmental history of the former British colony reveals that these relations of control, domestication, and domination over nature are colonial inheritances. Since the island’s colonisation in 1819, deforestation for plantation agriculture has led to 95% of habitat loss, resulting in what scientists estimate to be local extinction rates of up to 73%.27 In their words, these extinctions were nothing short of “catastrophic.” At the same time, colonial scientists began the work of documenting, collecting, and taxonomising the island’s flora, fauna, and humans.28 Care emerges as imperial nostalgia amidst an ecocide.29

During Singapore’s nearly two-month-long “circuit breaker” period, unexpected stirrings of plant-human relations occurred. While the National Parks Board (NParks) offered vegetable seeds for households upon request, social media saw the rise of “plant parents” and their luxuriant aesthetics of indoor plants, sometimes couched in the terms of heteronormative class display.30 Whether these more-than-human stirrings could move beyond colonial scripts remains to be seen. And the same could be said for The Garden as Question.

Unpacking the power dynamics around care is neither about abandonment nor cynical inertia. In the words of feminist anthropologist Juno Salazar Parreñas from her book, Decolonizing Extinction, “this is not the time to fatalistically give up on caring how others try to eke out a living under dire circumstance”.31 Maria Puig de la Bellacasa reclaims care as an “ethico-affective everyday practical doing that engages with the inescapable troubles of interdependent existences.”32 To care is to enable openings for uncertain, mutually vulnerable, and transformative relations— ways of living and dying together.

The Garden as Question is not an impressive garden. To some, the garden is unkempt with its browning organic matter and disorderly planting. But a modicum of attentiveness also shows how these patchy aesthetics are also expressions of vegetal generosity. In the weeds’ refusal, they are mattered into compost. Dead and dying vegetation become shade, parceling out a diversity of microclimates. Seedlings sprout and bunch together, some persist, others make space, mattering back into compost. The garden hosts co-conspirators, tending to encounters, observations, and speculations.

Attentiveness, attendant, attending, tending: unpacking this many-splendored bundle of concepts has revealed fewer straightforward “solutions” towards “problems” that today’s crises have shored up. I am reminded that words will not save us. In fact, these concepts are predicaments in themselves, instead, if anything, imbricating us towards a thick field of predicaments, ones that requires multiple modes of involvement without promise of resolution.33

From the vantage point of a singular rooftop garden, it is salvific to fantasize about ameliorating these crises alone. Following author Ursula K. Le Guin, “to put a pig on the tracks” on narratives of growth, a rooftop garden has to be attentive to its patchwork ecology, an emergent pullulation of micro-farms, sidewalk carbon sinks, research units on speculative futures, forest playgrounds, more-than-human curriculums, compost cooperatives, DIY fungi laboratories, degrowth collectives, vegetal sensoriums.34

Our collaborative lifeways of learning, pleasure, and play with non-humans are too precious to leave to the uncaring of the powers that be.

Notes

- Longkang is Malay for drain.

- soft/WALL/studs’ soil-raised weed garden project, The Garden as Question: Words will not save us, is one of many programmes under Beyond Repair, a series supported by National Gallery Singapore and Singapore Art Museum as part of Proposals for Novel Ways of Being. A regularly updated garden log could be found on https://softwallstuds.space/Garden.

- In dwelling on these observational practices, I take cue from Anna Tsing’s “arts of noticing,” which are the attentive practices paid towards the world-making capacities of humans and non-humans “simultaneously for themselves and others.” See Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

- Akiko Busch, The Incidental Steward: Reflections on Citizen Science (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013): p. 65.

- Natasha Myers, “Sensing Botanical Sensoria: A Kriya for Cultivating Your Inner Plant,” Imaginings series, Centre for Imaginative Ethnography, 2014, https://imaginative-ethnography.com/imaginings/affect/sensing-botanical-sensoria/

- In the process of cultivating The Garden as Question, identification was not only limited to a strict Linnaean taxonomy, but also involved imaginative acts of naming and myth-making around the garden’s various enigmatic creatures, such as fire aphids or cucumber pigeons.

- Myers, “Sensing Botanical Sensoria”.

- Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, “On Nonscalability: The Living World is Not Amenable to Precision-Nested Scales,” Common Knowledge 18, no. 3 (Fall 2012): p. 505-524.

- Arundhati Roy, “A Global Green New Deal: Into the Portal, Leave No One Behind.,” Arundhati Roy and Naomi Klein in conversation, moderated by Asad Rehman on 19 May 2020, Haymarket Books, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w0NY1_73mHY.

- Will Steffen et al., “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene,” PNAS 115, no. 33 (2018): p. 8252-8259.

- A June 2020 press release by the World Bank has confirmed that the 2020 global economic recession will be the “worst recession since World War II”. In the span of nine months in 2020, California and Australia has seen intensified wildfires, China, Indonesia, and India have experienced severe floods, while desert locust swarms—the most severe in the last 70 years in Kenya— have spread through East Africa, the Middle East, and the Indian subcontinent. See World Bank, “COVID-19 to Plunge Global Economy into Worst Recession Since World War II”, press release on 8 June 2020, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/06/08/covid-19-to-plunge-global-economy-into-worst-recession-since-world-war-ii. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Current Upsurge (2019-2020),” Locus Watch: Desert Locust, http://www.fao.org/ag/locusts/en/info/2094/index.html.

- Roy Gibb et al., “Zoonotic host diversity increases in human-dominated ecosystems”, Nature 584 (2020): p. 389-402. Stanley Perlman, “Another Decade, Another Coronavirus”, The New England Journal of Medicine 382, no. 8 (2020): p. 760-762. At the onset of the pandemic, blame over the ecological spillover was pinned on Chinese wet markets. These racist sentiments over "hygiene" often fail to recognize the political geography of capitalism that makes living on ecological frontiers vulnerable for both nonhumans and humans alike. For a materialist analysis, see “Social Contagion: Microbiological Class War in China”, Chuang 2 (2020), http://chuangcn.org/2020/02/social-contagion/.

- Beth Gardiner, “In Pandemic Recovery Efforts, Polluting Industries are Winning Big”, Yale Environment 360, 23 June 2020, https://e360.yale.edu/features/in-pandemic-recovery-efforts-polluting-industries-are-winning-big.

- Ministry of Trade and Industry, Singapore, “Emerging Stronger Taskforce to Provide Recommendations to the Future Economy Council (FEC) on Post-Covid-19 Economy”, press release on 6 May 2020.

- Lee Hsien Loong, “National Day Rally 2019”, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, delivered on 18 August 2020.

- In the wake of city-wide lockdowns across the world, CO2 emissions pathways have rebounded to pre-COVID-19 as temporary reductions did not reflect long-term structural changes. Corinne Le Quéré et al., “Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement”, Nature Climate Change 10 (2020), p. 647-653.

- The online meme has ecofascist, genocidal undertones that echoes the myth of overpopulation popularized Paul Eirich. For a critique on the meme, ecofacism, and modern environmentalism’s racist roots, see Deja Thomas, “The Dark Side of Environmentalism: Ecofacism and COVID-19”, University of San Francisco, Office of Sustainability Blogs, 15 April 2020, https://usfblogs.usfca.edu/sustainability/2020/04/15/the-dark-side-of-environmentalism-ecofascism-and-covid-19/. See also Thomas Wiedmann, Manfred Lenzen, Lorenz T. Keyßer and Julia K. Steinberger, “Scientists’ warning on affluence”, Nature Communications 11 (2020).

- Natasha Myers, “How to grow liveable worlds: Ten (not-so-easy) steps for life in the Planthroposcene”, ABC Religion & Ethics, 28 January 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/religion/natasha-myers-how-to-grow-liveable-worlds:-ten-not-so-easy-step/11906548.

- Saira Asher, “Coronavirus in Singapore: The garden city learning to love the wild,” BBC News, Singapore, 14 June 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52960623. Audrey Tan, “Spy the native biodiversity among the wildflowers amid Covid-19 circuit breaker,” The Straits Times, 23 May 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/spy-the-native-biodiversity-among-the-wildflowers. See also Loo Zihan, Temporary Measures - In Correspondence, 2020.

- Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World, p. 22-24.

- Timothy Choy, “Tending to Suspension: Abstraction and Apparatuses of Atmospheric Attunement in Matsutake Worlds”, Social Analysis 62, no. 4 (Winter 2018): p. 54-77.

- Eve Tuck and Wayne K. Yang, “R-Words: Refusing Research” in Humanizing Research: Decolonizing Qualitative Enquiry with Youths and Communities, ed. Django Paris and Maisha T. Winn, (Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage Publications, 2014).

- Apart from the burgeoning scholarly literature, curatorial and artistic practices surrounding ‘care’, I am thinking here of mutual aid projects and thinking that have emerged during COVID-19. Specific to Singapore, see wares, 2020- , Mutual Aid and Community Solidarity- Coordination, http://tinyurl.com/waresmutualaid. Diana Rahim, “Notes of Mutual Aid”, out of isolation: artists respond to covid-19, Perspectives Magazine, National Gallery Singapore, 14 July 2020, https://www.nationalgallery.sg/magazine/out-of-isolation-covid-19-diana-rahim-notes-on-mutual-aid.

- Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, “Making Time for Soil: Technoscientific futurity pace of care”, Social Studies of Science 45 , no. 5 (October 2015): p. 691-716.

- Ibid., p. 707.

- The authors cite the landscape design of the National University of Singapore (NUS), whereby “baking plateaus of lawn and paving” where used to discourage gatherings following an unrest in 1968. Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing, “Paramilitary Gardening: Landscape and Authoritarianism,” uploaded 6 September 2016, https://whysingaporeblog.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/paramilitary-gardening.pdf.

- Barry W. Brook, Navjot S. Sodhi, Peter K. L. Ng, “Catastrophic extinctions follow deforestation in Singapore,” Nature 424 (2003): p. 420-423.

- Timothy P. Barnard, Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2019).

- Timothy Choy borrows the term, “imperial nostalgia” from anthropologist Renato Rosaldo, pointing to a “mode or affect” characteristic of “work by Western anthropologist and critics who described and bemoaned cultural loss or natural degradation in the global South,” where, through this nostalgia, “we might mourn the loss of something whole disavowing our complicity in destroying it”. Timothy Choy, Ecologies of Comparison: An Ethnography of Endangerment in Hong Kong (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011): p. 40.

- Jan Lee, “Covid 19 has led to a botanic bloom in Singapore as more people become plant parents to relieve stress,” The Straits Times, 31 July 2020.

- Juno Salazar Parreñas, Decolonizing Extinction: The Work of Care in Orangutan Rehabilitation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018): p. 30.

- Emphasis in original. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, “‘Nothing comes without its world’: Thinking with care,” The Sociological Review 60 (2012): p. 197-216.

- Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures, “Preparing for the end of the world as we know it”, accessed 12 September 2020, https://decolonialfutures.net/portfolio/preparing-for-the-end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it/. On involving and involution, as opposed to co-evolution, see Carla Hustak and Natasha Myers, “Involuntary Momentum: Affective Ecologies and the Sciences of Plant/Insect Encounters,” differences 25, no. 5 (2012): p. 74-118.

- Ursula K. Le Guin, “A Non-Euclidean View of California as a Cold Place to Be,” Dancing at the Edge of the World (New York: Grove Press, 1989). In many senses, these pullulations have already begun. On ‘micro-farms’, I borrow soil companion from the “Soil Regeneration Project”, Mr Tang HB’s proposal to transform Singapore’s manicured lawns and sidewalks into micro-farms. The notion of ‘sidewalk carbon sinks’ further draws from his suggestion to think about ‘carbon handprints’— labours towards carbon sequestration—as opposed to mere reduction of carbon footprint towards climate change mitigation. See Soil Regeneration Project, https://soilregenerationproject.com/ and Subhadip Ghosh, Bryant C. Sharenbroch and Lai Fern Ow, “Soil organic carbon distribution in roadside soils of Singapore”, Chemosphere 165 (2016), 163-172. On ‘research units on speculative futures’, see soft/WALL/studs’ Futures Writing Research Unit, also under the series, Beyond Repair, https://softwallstuds.space/Futures. On ‘forest playgrounds’, I am reminded of nature’s affordances in play and pedagogy during my brief stint as a coach for Forest School Singapore. See Al Lim and Feroz Khan, “Learning to Thrive: Educating Singapore’s Children for a Climate-Changed World” in Eating Chili Crab in the Anthropocene, ed. Matthew Schneider-Mayerson (Singapore: Ethos Books, 2020).